Abstract

Arterial hypertension is among the leading global risks for mortality, being responsible for 9.4 million deaths in 2010.

The reason for this enormous burden has been documented in multiple studies. Hypertension is strongly associated with overall cardiovascular risk. Increased blood pressure contributes to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular endpoints, such as myocardial infarction, heart failure, cardiovascular death and stroke. In addition, an age-dependent positive correlation exists between systolic blood pressure (SBP)/ diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and stroke, as well as between SBP/DBP and ischaemic heart disease. All these data suggest that hypertension is the number one risk for mortality because of its dominant role in cardiovascular pathogenesis.

Despite a recently documented fall in blood pressure levels during the last decade in Europe, it appears very likely that hypertension, as a strong age-dependent risk factor, will remain one of the most crucial cardiovascular risk factors in an ageing world population.

Along these lines, the well-known suboptimal hypertension control rates should be of great concern, and the identification and study of new strategies for an improvement in awareness and effective treatment for hypertension are absolutely essential.

Introduction

Arterial hypertension is among the leading global risks for mortality. In 2004 high blood pressure accounted for 7.5 million deaths worldwide, representing 12.8% of the global total1. In 2010, hypertension was the leading single risk factor, being responsible for 9.4 million deaths worldwide2.

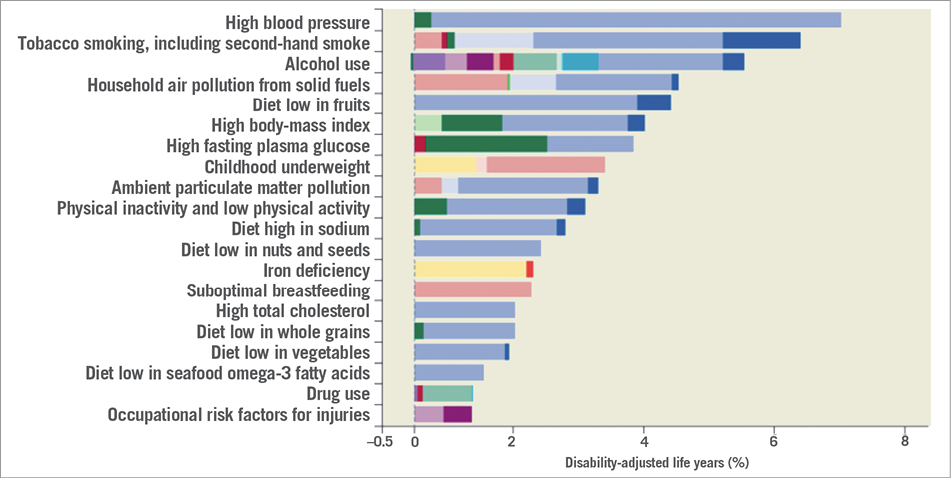

When speaking about the burden of a disease, one may start by looking at the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of disease burden: “a measurement of the gap between current health status and an ideal situation where everyone lives into old age, free of disease and disability”1. A measure of disease burden or the described health gap is provided by so-called “DALYs” (disability-adjusted life years), a sum of two components: years of life lost due to premature mortality (YLL) and years lived with disability (YLDs)3. Recently, Lim and colleagues provided an excellent comparative analysis of 67 risk factors which mainly influence death and DALYs. This study demonstrated that high blood pressure is the number one risk factor followed by tobacco smoking and alcohol use, contributing to 9.4 million deaths and 7.0% of the global DALYs in 20102 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Burden of disease attributable to 20 leading risk factors in 2010, expressed as percentage of global DALYs (disability-adjusted life years). Reproduced with permission from reference 2.

What makes hypertension the number one risk factor? It is well established that hypertension is strongly associated with overall cardiovascular risk. Increased blood pressure contributes to multiple cardiovascular and cerebrovascular endpoints, such as myocardial infarction, heart failure, cardiovascular death and stroke. An age-dependent positive correlation exists between systolic blood pressure (SBP)/ diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and stroke, as well as between SBP/DBP and ischaemic heart disease4. When considering a middle-aged population, this correlation would translate into a 10% lower stroke mortality, and about a 7% lower mortality from ischaemic heart disease when the usual SBP would be 2 mmHg lower4. From another perspective it has been shown that 54% of stroke and 47% of ischaemic heart disease worldwide are attributable to high blood pressure5. Taken together, these data suggest that hypertension is the number one risk for mortality because of its dominant role in cardiovascular pathogenesis.

Regional differences and changes over time

The trend in blood pressure differs depending on the world region: consequently, this results in regional differences in the burden of blood-pressure-related disease. Danaei and colleagues have published a comprehensive analysis of SBP levels since 1980 including health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 5.4 million participants in 199 countries and territories6. From 1980 to 2008, age-standardised SBP levels fell predominantly in high-income regions such as Western Europe, North America, and high-income Asian-Pacific countries6. In Western Europe, for example, male SBP fell by 2.1 mmHg per decade. Viewed through a European lens, Western European women and men still had the highest SBP of all high-income regions6. In other regions SBP decline was more moderate, e.g., –1.1 mmHg per decade in Central Europe, and –1.5 mmHg in Eastern Europe. Also viewed through the European lens, these regions still had the highest SBP values in women and men in 2008 worldwide. Finally, in some regions of Africa and Asia a clear increase in SBP was documented. The driving forces of this development are mostly unknown but may include access to antihypertensive medication, as well as dietary aspects.

Despite the falls in blood pressure levels during the last decade in Europe, the overall prevalence of cardiovascular disease will still rise because of an ageing population in high-income regions. This development has recently been confirmed by Murray and colleagues who showed an increase in DALYs of 29% for ischaemic heart disease and 19% for cerebrovascular disease from 1990 to 20103. Taken together, it appears to be very likely that, as the number of older patients increase, and despite the recently documented fall in blood pressure levels in Europe, hypertension as a strong age-dependent risk factor will remain one of the most crucial cardiovascular risk factors in the future.

Fighting the burden of hypertension

Effective blood pressure lowering has consistently been shown to reduce overall cardiovascular risk7. Independently of the chosen blood pressure lowering regime, most of the randomised clinical intervention trials demonstrated that a larger decrease in blood pressure also resulted in a larger reduction of cardiovascular risk7. Hypertension control rates are still suboptimal despite the knowledge both about hypertension being the most important cardiovascular risk factor, and about the effectiveness of antihypertensive treatment on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1988-1994 and 1999-2008 showed that hypertension control in the USA improved from 27.3% in 1988-94 to 50.1% in 2007-2008 with almost 50% of patients still not reaching their target blood pressure8. In agreement with this, a recent analysis of observational and clinical studies performed in Italy and published between 2005 and 2011 confirmed the poor control rate for European countries as well, with only 37% of treated hypertensive patients achieving recommended blood pressure values9.

The burden of resistant hypertension

Closely connected to the poor hypertension control rate is the problem of resistant hypertension. According to international hypertension guidelines, resistant hypertension is defined as an increased blood pressure of >140/90 mmHg under antihypertensive treatment with at least three antihypertensive drugs one of which should be a diuretic. Looking at the prevalence of resistant hypertension, reported numbers vary markedly. Data from NHANES reported a prevalence of 12.8% for US adults treated for hypertension10. Results from a Spanish registry of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring showed a comparable prevalence of 14.8%11. However, results from clinical trials such as ASCOT (Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcome Trial), ALLHAT (Antihypertensive and Lipid Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial), or ACCOMPLISH (Avoiding Cardiovascular Events in Patients Living with Systolic Hypertension) demonstrated a markedly higher prevalence, between 25% and 35% of treated patients12. Combining clinical trial data and results from recent observational studies, the prevalence of resistant hypertension appears to range between 15% and 30% of treated hypertensive patients12. More importantly, Daugherty and colleagues recently reported that patients with resistant hypertension exhibit a much higher risk for cardiovascular events with a hazard ratio of 1.47 (95% CI: 1.33-1.62) when compared to patients without resistant hypertension13.

In conclusion, hypertension is the number one risk factor for mortality in the world. The burden of this disease is enormous with respect to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, and increases markedly in cases of resistant hypertension. Hypertension is a strong age-dependent risk factor indicating that high blood pressure will gain even more importance in terms of mortality with an ageing world population. Despite the established epidemiological and clinical knowledge, hypertension control rates are still far from being optimal, and treatment-resistant hypertension becomes more and more important. Therefore, new strategies for an improvement of awareness and effective treatment are absolutely essential.

Conflict of interest statement

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.