Abstract

Aims: To evaluate practice patterns in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), focusing on the United Kingdom (UK).

Methods and results: The Antiplatelet Therapy Observational Registry (APTOR) is a prospective observational study of consecutive ACS patients undergoing PCI (N=1525) from January-August 2007 in the UK, France, and Spain. In the UK, median time from hospital admission to PCI was one day post-admission (IQR 0,4) among STEMI patients and five days (IQR 2,9) among unstable angina/non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (UA/NSTEMI) patients. Patients in the UK most frequently received a 300 mg aspirin loading dose (85%), 300 mg clopidogrel loading dose (70%), and 75 mg clopidogrel maintenance dose (99%). Loading dose was given on the day of hospitalisation to 80% of STEMI patients and 68% of UA/NSTEMI patients. Clopidogrel was discontinued by 12 months in 30% of UK patients. Length of hospitalisation was similar between the three countries.

Conclusions: Despite established consensus guidelines for ACS patient management, APTOR data show disparity in management practices for ACS patients undergoing PCI in the UK and two other European countries. These data can help provide focus for areas of ACS management requiring improvements to meet guideline therapy, including reducing time from hospitalisation to PCI and maintaining 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy for all ACS patients undergoing stenting.

Introduction

In 2007 in the United Kingdom (UK), 91,458 men and women died from coronary heart disease1. An estimated 141,000 individuals experienced a new myocardial infarction and two million people suffer from angina1. A large number of patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in the UK and Western Europe undergo cardiac catheterisation, often with treatment with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in addition to pharmacological therapy2. ESC guidelines recommend early diagnostic cardiac catheterisation and PCI within two hours for ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients and 72 hours for non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) patients, along with dual antiplatelet therapy for 12 months when stents have been employed3-5. Despite guideline recommendations, variation in ACS management and PCI practice patterns exist between European countries6.

While several observational studies have reported on general ACS management patterns in Europe7-12, specific details on patient management strategies are not widely available, including delays in PCI and antiplatelet administration. The Antiplatelet Therapy Observational Registry (APTOR) 12-month study aims to address these issues by following concurrently recruited ACS patients from the UK, France, and Spain in a “real world” clinical setting. The present manuscript presents specific details of ACS patient management in the UK, including stent use, time to revascularisation, and location, timing, dose, and duration of antiplatelet treatment.

Methods

Study design

APTOR is a non-interventional, prospective observational cohort study enrolling patients presenting with ACS undergoing PCI during January 2007 to August 2007 from 122 sites from the UK (n=29), France (n=71), and Spain (n=22) with a median age of 61 years. Data were collected about country-specific patterns of health care used in ACS patient management at teaching and non-teaching centres. Patient demographics, medical history, clinical characteristics, treatments and procedures, and clinical outcomes were recorded for patients by index diagnosis at hospital admission, PCI, and hospital discharge, and at three and 12-months post-discharge. An independent steering group of four international cardiologists who are also authors of this paper oversaw the design, conduct and analysis of the registry.

Study population

Patients enrolled in this study had a diagnosis of ACS requiring PCI with either initiation or continuation of any antiplatelet therapy. Once the study was initiated at a site, all consecutive presenting ACS patients who were undergoing PCI with associated antiplatelet therapy were invited to join the study. Patient care and treatment strategies were at the discretion of the patient and physician. This manuscript presents data for subjects enrolled in the UK. However, limited data from France and Spain are also presented to place the findings from the UK in perspective.

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics for continuous variables include median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables data presented include counts and percentage. Event rates at 12 months are reported as Kaplan-Meier estimates with 95% confidence intervals based on the time from PCI to clinical event, last visit or end of study (12 months), whichever came first. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

One-third of the 1,525 ACS patients enrolled were from the UK (n=504), with the remainder from France (n=483) and Spain (n=538). The majority of patients in APTOR in the UK were enrolled at a teaching hospital (72%). Among the 29 active sites in the UK, the median number of PCIs performed annually was 450 (min-max, 75-3,000).

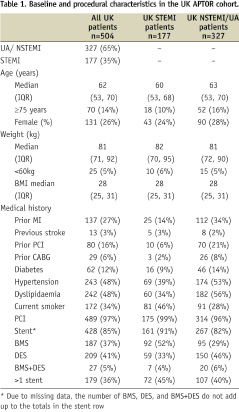

Among UK patients, the index diagnosis was UA/NSTEMI in 65% of subjects and STEMI in 35%, similar to the distribution in the overall APTOR study (62% and 38%, respectively; Table 1).

There were slightly more female subjects in the UK (26% vs. 18% in France and 22% in Spain) and a slightly lower percentage of subjects with diabetes (12% in the UK vs. 16% in France and 31% in Spain) and history of hypertension (48% in the UK vs. 51% in France and 61% in Spain). The median age of subjects in the UK was 62 years; 14% of patients were age ≥75 years, with a slightly higher percentage in the NSTEMI/UA cohort (16%) than in the STEMI cohort (10%). Prior MI, prior PCI, history of hypertension, and history of dyslipidaemia were more frequent in the UK NSTEMI/UA cohort than in the UK STEMI cohort (Table 1).

Antiplatelet therapy and patterns of use

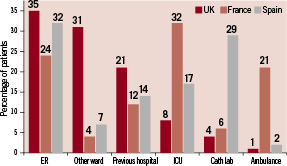

In the UK, most patients received the loading dose either in the emergency room (35%) or another ward within the study hospital (31%), with very few receiving it in the catheterisation laboratory (4%). The most common site for receiving the first clopidogrel loading dose overall in APTOR patients and in the UK was the emergency room (30% overall; Figure 1). However, location of loading dose varied by country (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Location of first clopidogrel loading dose by country.

Patients in the UK most frequently received a 300 mg loading dose of clopidogrel (70%), with 21% receiving >300 mg and 9% receiving <300 mg. Nearly all UK patients received a 75 mg maintenance dose of clopidogrel (99%), with <1% receiving a 150 mg maintenance dose. For the aspirin dose, the majority of UK patients were loaded with 300 mg (85%) followed by a maintenance dose of 75 mg (92%).

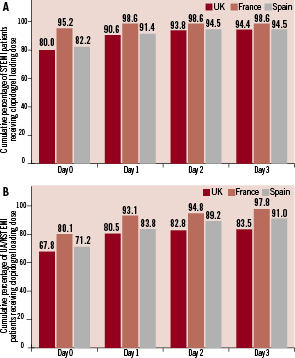

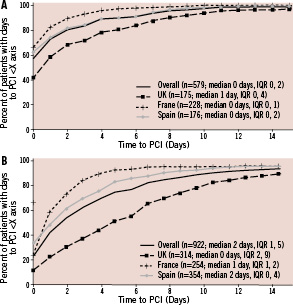

In the UK, 80% of STEMI patients received the clopidogrel loading dose on the day of hospital admission, as compared with 95% in France and 82% in Spain (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. A) Cumulative frequency of days from hospital admission to clopidogrel loading dose among STEMI patients by country. B) Cumulative frequency of days from hospital admission to clopidogrel loading dose among UA/NSTEMI patients by country.

By day three, 6% of STEMI patients in the UK had not received a clopidogrel loading dose. Among UA/NSTEMI patients, 68% of UK patients received the clopidogrel loading dose on the day of hospital admission, as compared with 80% in France and 71% in Spain (Figure 2B). By day three, 17% of UA/NSTEMI patients in the UK had not received a clopidogrel loading dose.

In the UK, approximately one-third of subjects discontinued clopidogrel by 12 months (30%). Although more patients in the UK with bare metal stents (BMS) only discontinued clopidogrel than those who received drug-eluting stents (DES) (43% vs. 15%), the median time to discontinuation was similar (89 days with BMS, IQR 57, 182; 84 days with DES, IQR 28, 209). Likewise, slightly more STEMI patients in the UK discontinued clopidogrel than UA/NSTEMI patients (36% vs. 26%) but the median time to discontinuation was similar (84 days for STEMI, IQR 28, 148; 86 days with UA/NSTEMI, IQR 28, 224).

Revascularisation

In total, PCI was performed in 99% of patients and 93% received stent implantation. Stent use varied by country, with 85% of patients in the UK receiving stents (Table 1) versus 96% in France and 97% in Spain. DES use also varied by country, with 55% stented patients in the UK receiving DES and 45% receiving BMS (Table 1). The percentage of DES use was lower than the UK in France (33%) and higher than the UK in Spain (72%). The use of stents was more common in the UK STEMI cohort than the UK NSTEMI/UA cohort (91% vs. 82%), with higher bare metal stent use (52% vs. 29%) and lower drug-eluting stent use (33% vs. 46%) in STEMI patients (Table 1).

Among STEMI patients, median time from hospital admission to PCI was one day post-admission (IQR 0, 4) in the UK and the day of admission (IQR 0, 1) in France and in Spain (IQR 0, 2) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. A) Days from hospital admission to PCI among STEMI patients for each country and overall (pooled data). B) Days from hospital admission to PCI among UA/NSTEMI patients for each country and overall (pooled data).

While 58% of STEMI patients in the registry overall underwent PCI on the day of hospital admission, 42% did so in the UK compared with 66% in France and 62% in Spain. Among UA/NSTEMI patients, the median time from hospital admission to PCI was five days (IQR 2, 9) in the UK, one day (IQR 1, 2) in France, and two days (IQR 0, 4) in Spain (Figure 3B). The majority of UA/NSTEMI patients overall underwent PCI within two days of hospital admission (56%); this percentage was lower in the UK (31%) compared with France (76%) and Spain (63%).

Length of hospitalisation

Despite longer delays in time from hospitalisation to PCI in the UK, length of hospitalisation was similar between countries. Among STEMI patients, the median stay was five days (IQR 4, 8) in the UK, six days (IQR 4, 9) in France, and seven days (IQR 5, 9) in Spain. Among UA/NSTEMI patients, the median stay was seven days (IQR 4, 12) in the UK, five days (IQR 4, 8) in France, and six days (IQR 3, 8) in Spain.

Clinical outcomes

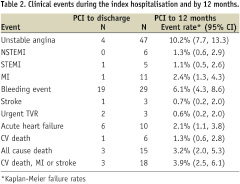

From PCI to hospital discharge, the number of clinical events was low (Table 2), with only three patients experiencing the composite of cardiovascular death, MI or stroke.

There were six subjects with acute heart failure during the index hospitalisation and four subjects with unstable angina. There was one cardiovascular death in a NSTEMI/UA patient and no cardiovascular deaths in the STEMI cohort.

From PCI to 12 month follow-up, 3.2% of patients had died, with less than half classified as cardiovascular death (1.3%) (Table 2). Of the cardiovascular deaths, three occurred in the STEMI cohort and three in the NSTEMI/UA cohort. The most frequent event during follow-up was unstable angina, which occurred in 10.2% of patients. A new MI was reported in 2.4% of patients (STEMI 1.1% and NSTEMI 1.3%) and stroke in 0.7%. The composite of CV death, MI or stroke occurred in 3.9% of patients by one year. Of the 29 subjects with bleeding events (6.1%) during the one year follow-up, 19 had experienced the bleeding event during the index hospitalisation.

Discussion

Although many ACS patients in the UK are managed according to European consensus guidelines3,5, not all aspects of guideline-recommended care are practiced routinely as evidenced by the present study. Variation was evident in several practices, including time from hospitalisation to PCI, timing and location of dosing of antiplatelet therapy, and length of antiplatelet therapy.

Several differences were noted in revascularisation strategies, including less stent use and a longer time from hospital admission to PCI in the UK than in France or Spain. Stent use in the UK in APTOR was 85%, somewhat lower than the 94.7% rate reported in the 2007 report of the National Coronary Angioplasty Audit13. However, there was a slight decline in stent use noted in the 2008 National Coronary Angioplasty Audit, to 92%14. The percentage of drug-eluting stents was identical to that observed in the National Coronary Angioplasty Audit in 2007 at 55%13 and similar to that in 2008 at 58%14, which represents a decline in DES use from 2005 and 2006, when it peaked at 63.5%. There was a notable difference in the frequency of both stent use and type of stent used in APTOR patients in the UK when examined by presenting syndrome of STEMI or NSTEMI/UA.

Time to PCI in the UK cohort was longer than the ESC guideline recommendations of within the first day for STEMI patients and within 72 hours for NSTEMI patients3-5, with less than half of STEMI patients undergoing PCI on the day of admission and less than one-third of UA/NSTEMI patients undergoing PCI within two days of admission. This finding is likely reflective of the percentage of patients who first presented to a previous hospital without on-site catheterisation facilities, and is supported by the fact that 21% of patients received the clopidogrel loading dose at a previous hospital (Figure 1). In the 2008 National Coronary Angioplasty Audit, the mean time from door to PCI was 3.0 days in UA, NSTEMI or convalescent STEMI patients with direct admission13,14. For STEMI patients, delayed versus early (within the first 12 hours) PCI have been associated with increased in-hospital mortality15. Nevertheless, while differences in time to PCI and type of stents used were noted (as well as differences in timing and location of dosing of antiplatelet therapy), length of hospitalisation was generally similar between the countries, suggesting that differences in revascularisation approaches may not significantly impact the duration needed for acute patient management. While centres in France and Spain took patients to the catheterisation laboratory more quickly, the UK was more efficient in discharge once the procedure occurred. Another possible explanation may be selection bias as to which patients undergo PCI in the different countries.

Antiplatelet patterns also varied in the UK compared to other countries, including location of dosage and duration of antiplatelet use. ESC guidelines currently recommend an aspirin loading dose of 150-325 mg and a maintenance dose of 75-100 mg3,5. UK patients tended to receive the higher end range for the aspirin loading dose, of 300 mg, but the lower range for the maintenance dose, of 75 mg. A significant benefit of higher dosages of aspirin in ACS patients has not been demonstrated, but higher dosages have been associated with increased bleeding events, primarily gastrointestinal16. This seems to be supported by UK APTOR data, which showed a relatively high rate of bleeding during the index hospitalisation but a lower rate from discharge to one year, as 19 of the 29 patients with a bleeding event did so during the index hospitalisation.

Per the ESC guideline recommendation3,5, the large majority of patients in the UK received a 300 mg loading dose of clopidogrel followed by a 75 mg maintenance dose. The timing of the loading dose, however, was somewhat delayed in the UK relative to France and Spain, a finding that is likely due to differences in delays from hospital admission to PCI in the UK for those patients who received the loading at the time of PCI. Delay in timing of clopidogrel loading dose is also likely due to both system-level issues as well as how the patient makes first medical contact (e.g., ambulance, emergency department, hospital with vs. without on-site catheterisation laboratory). Indeed, the time from symptom onset to clopidogrel loading dose will likely decline in 2008 and onward following the National Health Service recommendation to administer clopidogrel to STEMI patients in the ambulance prior to hospitalisation in the UK17.

While nearly all patients were on both clopidogrel and aspirin maintenance therapy at hospital discharge, only 63% of patients in the UK continued dual therapy by 12 months despite the recommendation of guidelines to maintain 12 months of dual therapy with both aspirin and clopidogrel where possible3,5. Use of clopidogrel at one year was lower in patients who received only a bare metal stent. However, guidelines recommend 12 months of clopidogrel in all ACS patients receiving a stent, irrespective of the type of stent used3,5. Studies such as the HORIZONS-AMI trial have found that bare metal stents may have similar rates of stent thrombosis through one year compared to drug-eluting stents18.

This analysis from APTOR demonstrates that while several of the recommendations for the management of ACS patients undergoing PCI in the UK are being met, including use of a 300 mg clopidogrel loading dose and a low aspirin maintenance dose, not all benchmarks in the current European guidelines have been reached, including with respect to timing of PCI and duration of antiplatelet administration. While data reported from APTOR cover the time period of 2007-2008, and it is possible that real-time findings might differ, these data should help provide a focus for areas of needed improvement in the management of UK ACS patients to meet guideline recommendations, including reducing time from hospitalisation to PCI and maintaining 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy for all ACS patients undergoing stent implantation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sabina A. Murphy for assistance in preparing the manuscript and Nathan Carter for statistical support. Mr. Carter is an employee of i3 Statprobe.