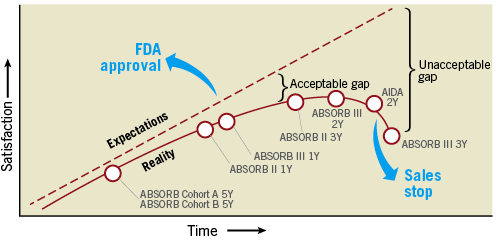

The background story is quite well known among interventional cardiologists, so it will not take too much text to summarise it. Since September 2017, approximately six years after it obtained Communauté Européenne (CE) approval, the Absorb™ bioresorbable vascular scaffold (BVS) (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) has no longer been available in the European market. During this time of frequent ups and downs (Figure 1), four sponsored studies cumulatively encompassing 3,389 patients compared the outcomes of the BVS with those of its everolimus-eluting drug-eluting stent (DES) counterpart, XIENCE® (Abbott Vascular). The three-year results of these studies are now in the public domain and meaningfully summarised by an individual-patient meta-analysis by Ali et al, showing increased rates of target lesion failure and device thrombosis with the BVS between one and three years and cumulatively at three years1.

Figure 1. A brief history of the first-generation bioresorbable vascular scaffold from approval to sales stop, between expectations and reality, turning the initially acceptable gap with metallic drug-eluting stents into an unacceptable one.

With three-year data available at the patient level, one may wonder why the Editorial Board decided to publish another meta-analysis of long-term BVS outcomes from Kang et al in this issue of EuroIntervention2.

Indeed, there is one part of the BVS story which will never be known, at least on a large-scale level, and that is how the first-generation device compares at long term versus DES other than XIENCE. This is a relevant question because, in the “debriefing phase” that has followed the removal of the BVS from sale, many observers now suggest that the key reason for the failure of the first-generation device was the exaggerated success of its comparator. Ironically, the biocompatible, durable-polymer XIENCE DES showed not only better clinical outcomes, but also the same effect on vasomotion restoration and angina relief, two of the most anticipated hallmarks of the BVS philosophy3.

So, how would a BVS have compared versus another DES in the long term? To address this question, in the absence of head-to-head randomised trials, a well-conducted network meta-analysis is the best an interested reader can hope for. Essentially, a network meta-analysis uses direct evidence to generate indirect evidence: for example, if stent A was compared to stent C and stent B was compared to stent C, then –within certain boundaries– we are entitled to speculate on how stent A would compare with stent C. Of note, Kang et al previously published a network meta-analysis of stent trials using a similar approach but focusing on one-year outcomes4. They meta-analysed a total of 147 randomised studies including 126,526 patients and found a low risk of definite or probable stent thrombosis for all contemporary metallic DES, including biocompatible durable-polymer DES, biodegradable-polymer DES, and polymer-free DES. The BVS displayed an increased risk of device thrombosis compared with the XIENCE stent (mostly based on direct evidence) and the Orsiro (Biotronik AG, Bülach, Switzerland) biodegradable-polymer stent (based on indirect evidence).

The updated meta-analysis now published in EuroIntervention analysed a total of 91 trials with a mean follow-up of 3.7 years in 105,842 patients2. The network plot in Figure1 of this meta-analysis is a nice synthesis of the history of stent trials since RAVEL5. Clearly, the most studied stents so far have been the first- and second-generation durable-polymer DES (firstly as investigational products and then as comparators). A total of 23,790 patients have been randomised to the XIENCE DES at some point and somewhere in the galaxy of stent trials. The network geometry shows some closed loops (e.g., studies of A vs. B, B vs. C, and A vs. C) essentially pertaining to older stents. The existence of closed loops allows checking the consistency of direct and indirect comparisons. In contrast, many cross-trial comparisons of newer stents, including BVS, still rely on smaller numbers and indirect evidence. Those results should be accepted with caution.

If we acknowledge its inherent caveats and limitations, the beauty of the network meta-analysis methodology once applied to stent trials is the possibility of looking at the results from very different angles. From the BVS side, the results tell the story of a debacle, since all the controls were associated with lower rates of thrombosis at two years or longer, with various degrees of significance but with few doubts regarding the direction of the treatment estimate. If we are more interested in DES in general, the probable rank of current devices did not identify substantial differences across newer-generation DES with respect to stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction. The BVS, at least and not surprisingly, was better than bare metal stents with respect to target vessel and lesion revascularisation2.

A key message from the two meta-analyses from Kang et al is that the higher risk of thrombosis with the BVS compared with all other DES is not limited to the first year after implantation, but continues up to at least three years2,4. Many mechanisms have been advocated to explain the potential reasons, which are well covered elsewhere6. In the only randomised ABSORB trial with four-year follow-up available, there were no more thromboses with both the Absorb and XIENCE stents between three and four years7. Obviously, if your performance as a stent in the coronary of patients starts with a large gap, then it is very difficult to catch up, even under the assumption of no more events beyond three to four years, when the device has disappeared and should theoretically no longer act as a trigger for thrombosis8. Therefore, improving the initial performance of the device will be key for the BVS concept to survive. In the three-year meta-analysis from Ali et al, most clinical event rates between BVS and XIENCE were similar if patients with device thrombosis were excluded1. Promisingly lower rates of thrombosis were reported from an interim analysis of the ABSORB IV trial, where patient selection and procedural technique9 were better than in earlier studies (Stone GW. Presented at TCT 2017). The next-generation device will be thinner, which should decrease its intrinsic thrombogenicity10. You may bet that in future trials of BVS the antithrombotic therapy protocols will be somehow more aggressive, introducing another potential game changer11.

There are therefore some reasons to remain optimistic rather than discrediting the BVS concept once and for all. Current results belong to first-generation BVS devices. The concept itself deserves a second chance, provided that expectations are downplayed a bit10. The expected improvement in clinical outcomes by design improvements, dedicated implantation protocols and better patient management will require a scrupulous new round of systematic non-clinical and clinical testing according to standardised criteria. Based on consensus from the Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI)12, this should include data from a medium-sized randomised trial against DES powered for a surrogate endpoint of clinical efficacy and a large-scale randomised clinical trial with planned long-term follow-up. It will take many years for the BVS to appeal to the interventional community again, but you know the old saying … “good things come to those who wait”.