Abstract

Secondary prevention constitutes a key element in the management of coronary artery disease. In the subgroup of patients with prior coronary interventions, however, secondary prevention plays a distinct role derived from its effects on vessel native atherosclerosis progression, saphenous vein graft attrition and reduction of adverse events after percutaneous revascularisation. From this point of view, secondary prevention can be understood as a protective measure against repeat revascularisation. These benefits contrast with the yet suboptimal implementation of secondary prevention in clinical practice, stressing the importance of a comprehensive approach to coronary revascularisation.

Abbreviations

CABG: coronary artery bypass graft

PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

IVUS: intravascular ultrasound imaging

MACE: major adverse cardiac events

MI: myocardial infarction

BMS: bare metal stent

DES: drug eluting stent

RCT: randomised clinical trial

Introduction

Coronary revascularisation and cardiovascular prevention therapy are probably the most relevant contributions of cardiology to the improvement of life expectancy of patients with coronary artery disease. Initially reserved for the amelioration of myocardial ischaemia in stable angina, the advent of percutaneous techniques expanded its use to acute settings, becoming the method of choice (whenever available) for the treatment of acute myocardial infarction.

The importance of secondary prevention in patients with coronary artery disease has been widely acknowledged and constitutes one of the key aspects of health care in these patients. Multiple studies have demonstrated that long-term prognosis in cardiovascular patients is dependent on successful implementation of secondary prevention measures, in particular, risk factor modification by therapeutic lifestyle changes and the use of platelets inhibitors, lipid-lowering agents, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-inhibitors) and beta-blockers1,2. The information has been reviewed in clinical practice guidelines and recommendations have been issued in European secondary prevention guidelines3.

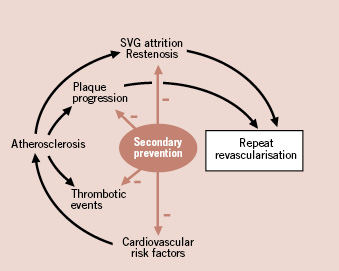

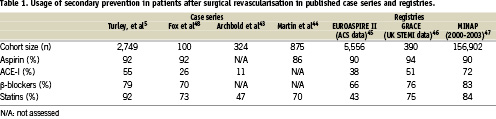

However, within the overall population of cardiovascular patients, those requiring multiple interventions constitute a subset with particular importance, both for the perspective of revascularisation as well as secondary prevention. The former aspects have been extensively covered in other articles encompassed in this current EuroIntervention special supplement. The latter, the distinct role of cardiovascular cardiovascular prevention after coronary revascularisation, follows from several different reasons. The first of these reasons is related to the higher benefit in terms of cardiac event reduction expected from treating patients which typically present a high-risk profile and a high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, diabetes and chronic renal failure4. The second is the impact that these measures may have on the progression of native coronary artery disease and the resulting need for subsequent revascularisation. Finally, the effect that secondary prevention may play in pathobiological responses to revascularisation techniques, such as endoluminal prosthesis or surgical grafts. Figure 1 depicts schematically these actions. However, it is a matter of concern that the prescription rate of secondary preventive medications in patients undergoing coronary revascularisation procedure is far from being optimal5. Available data from different registries and patient cohorts is summarised in Table 1.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the effects of secondary prevention therapy in patients with prior coronary revascularisation. When compared with other patients with coronary artery disease, a distinct benefit can be derived, in term of reduction of repeat revascularisation, from the effects of treatment on atherosclerosis progression and persistence of the results of primary revascularisation. See text for details.

The aim of this article is to review, using an evidence-based approach, the efficacy of secondary prevention strategies on three separate points: atherosclerosis progression, surgical conduit failure, and restenosis and cardiac events after percutaneous intervention. A discussion on how to improve adherence to secondary preventive recommendations is also made.

Secondary prevention and progression of coronary atherosclerosis

Following coronary revascularisation, native disease progression in treated or non-treated vascular segments has been recognised as a leading mechanism of recurrent myocardial ischaemia or angina. In this context, previous pharmacological strategies addressing atherosclerosis progression can be envisioned as preventive measures against repeated revascularisation. Different randomised clinical trials (CRT´s) on lipid-lowering agents, calcium channels blockers, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors (ACE-inhibitors) and anti-diabetic drugs in patients with coronary artery disease have included, in addition to clinical endpoints, indices of atherosclerosis progression or regression. These indices have been mostly based on quantitative coronary angiography or intracoronary ultrasound. In the following paragraphs we review some of these CRT´s of particular relevance for this article.

The effect of intensive vs. moderate statin therapy on atheromatous plaque progression and modification, assessed with IVUS, has been the subject of several CRT´s. The REVERSAL trial (REVERSing Atherosclerosis with aggressive Lipid lowering6) and the ASTEORID trial (effects of very high-intensity statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis)7, which studied the effect of atorvastatin 80 mg/d vs pravastatin 40 mg and rosuvastatin 40 mg/d respectively, demonstrated significant slowing and occasionally regression of atherosclerotic plaque burden in coronary disease patients associated with a significant reduction of LDL-cholesterol levels. From a wider, meta-analytic perspective, statin treatment has been associated with atherosclerotic regression. A meta-analysis by Gomez-Granillo et al with data from 11 studies (985 patients) in which the influence of statins on atherosclerotic burden was assessed longitudinally with IVUS found a significant reduction in atheromatous plaque volume associated of treatment8. However, further studies are needed to determine the translation of this plaque modification to clinical outcome.

The role of calcium channel blockers on stopping atherosclerotic progression has been addressed in the CAMELOT trial (Comparison of AMlodipine vs Enalapril to Limit Occurrences of Thrombosis)9. This trial randomised 1,991 patients with angiographically documented coronary artery disease to receive amlodipine 10 mg (calcium channel blocker) vs enalapril 20 mg or placebo. Atherosclerotic progression was assessed using intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) in a pre-specified subgroup of 274 patients. Patients allocated to amlodipine arm showed a significant reduction in cardiovascular events and IVUS revealed evidence of a slowing of atherosclerotic progression. Although the primary objective of this trial was the reduction of adverse cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease, the IVUS substudy of the trial showed a consistent relationship between reduction in blood pressure resulting from amlodipine treatment and atherosclerotic plaque regression9.

On the other hand, the anti-atherosclerotic properties of ACE inhibitors have been analysed in some clinical trials. One of these studies was the PERSPECTIVE study (PERindopril’s proSPECTIVE effect on coronary atherosclerosis by angiography and intra vascular ultrasound evaluation10), an imaging sub-study of the EUROPA trial (European trial on reduction of cardiac events with perindopril in stable coronary artery disease)11. The 244 patients of this substudy underwent angiographic and IVUS assessment at baseline and at 3-year follow-up; study endpoints were changes in minimum and mean luminal diameters measured by quantitative coronary angiography, and in plaque cross-sectional area measured by IVUS. Although the EUROPA trial was positive, with a significant reduction in cardiac events in the perindopril arm, the atherosclerotic regression endpoints of PERSPECTIVE were not reached. This apparent discrepancy is probably due to the preponderance of certain perindropril effects, such as normalisation of the endothelial function and other plaque-stabilising effects, over the sole regression of atherosclerotic plaque, and constitutes a reminder of the importance of ACE-inhibitors in secondary prevention.

Patients with diabetes mellitus are more prone to develop adverse cardiac events than non-diabetics12. Behind this fact stands the diffuse and accelerated character of atherosclerotic disease in the diabetic, with longer lesions, decreased luminal size and higher plaque burden13. To investigate whether in these patients atherosclerosis progression can be stopped by an anti-diabetic agent, the PERISCOPE trial (effect of pioglitazone versus glimepiride on progression of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with type 2 diabetes)14 compared the effect of pioglitazone, a novel insulin sensitising agent, with glimepiride, a conventional anti-diabetic drug, on the progression of coronary atherosclerosis in 543 type 2 diabetic patients with coronary disease. Progression of coronary atherosclerosis, assessed with IVUS as percent change in atheroma volume, was significantly lower in the pioglitazone arm, even when the glycemic control achieved was similar to that in the glimepiride arm. Although further trials are necessary to investigate how these findings translate into clinical outcome, they represent a fundamental observation demonstrating that pioglitazone, in addition to controlling glycemia, modulates atherosclerotic progression in type 2 diabetic patients.

Current RCTs have investigated the potential of new cardiovascular drugs on regression of coronary disease. The STRADIVARIUS trial (Strategy To Reduce Atherosclerosis Development InVolving Administration of Rimonabant: the Intravascular Ultrasound Study)15, demonstrated that rimonabant, a cannabinoid type 1 receptor inhibitor, significantly decreased the total atheroma volume (a secondary endpoint of the trial) in obese patients with metabolic syndrome. Although this study did not specifically address patients with coronary revascularisation, the results open new and promising avenues for research in this field.

Finally, the ILLUSTRATE trial (an Investigation on Lipid Level management using coronary UltraSound To assess Reduction of Atherosclerosis by CETP inhibition and HDL Elevation)16, investigated whether a combination of torcetrapib, a cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitor and atorvastatin were able to slow coronary atherosclerosis progression in high risk patients (60% with prior coronary revascularisation). Although this drug regime improved lipid profile, it failed to reduce the progression of coronary atherosclerosis (primary endpoint of the trial) documented by IVUS as percent change in atheroma volume. Even worse, an increase in major cardiovascular events in the treatment group led to premature cessation of the trial.

In summary, different drugs (statins, amlopidine and pioglitazone, and more recently rimonabant) seem to prevent or even regress atherosclerosis progression. No information is currently available, however, on whether this effect might translate into a lower need of future revascularisation, a hypothesis that might be tested in future clinical trials.

Importance of secondary prevention after CABG

In spite of the introduction of arterial grafts with internal thoracic arteries, aorto-coronary saphenous vein bypass grafts (SVGs) still play an important role in surgical coronary revascularisation, and there were millions of patients treated before the 90´s who only underwent this sort of graft. Graft failure can be early and late, with different underlying pathophysiological mechanisms. The main cause for early failure, excluding technical operative problems, is SVG thrombosis. In the long term, SVG accelerated atherosclerosis becomes the dominant aetiology. The difference between this and native vessel atherosclerosis, is that SVG atherosclerosis plaques are diffuse, concentric, cholesterol rich and non-calcific. They also are vulnerable, prone to rupture and to cause thrombus formation. These changes, absent in arterial grafts, explain why patency rates of SVG´s are much lower17.

Secondary prevention can play a major role in lengthening SVG life. Two pharmacological modalities have demonstrated efficacy in the prevention of SVG atherosclerosis or thrombosis: antiplatelet agents and lipid-lowering drugs. Antiplatelet therapy, early in the postoperative period, improves outcome after CABG and reduces the incidence of SVG atherosclerosis18. In a meta-analysis from the Antiplatelet Trialists’ collaboration, low-dose aspirin was associated with improved graft patency for an average of one year after surgery19. Higher pooled odds reduction for SVG closure was documented with low-dose aspirin (75 to 325 mg/day) compared to placebo or control therapy. This benefit was similar to that seen with higher and more gastro-toxic doses of aspirin. Beside, aspirin is inexpensive, is associated with few side effects and is known to be beneficial to all patients with coronary artery disease17. Therefore, starting from these results, aspirin should be indicated immediately after CABG to prevent graft occlusions during the first post-operative year and be continued indefinitely unless contraindications exist20. Thienopyridine use in this clinical setting is less supported. Bhatt et al21, analysing a subgroup analysis of patients with prior CABG included the CAPRIE trial (Clopidogrel versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischaemic Events) suggested that clopidogrel is superior to aspirin in reducing recurrent ischaemic events in patients with prior CABG and recent myocardial infarction, stroke or symptomatic peripheral vascular disease. Time elapsed from CABG operation, however, was not reported. It must be stressed that these findings were not the primary objective of the CAPRIE trial, and that therefore should be interpreted with caution. For patients who are allergic to aspirin, however, clopidogrel 300 mg loading dose six hour after surgery, followed by a maintenance dose of 75 mg/day is indicated in the ACC/AHA task force on bypass surgery20.

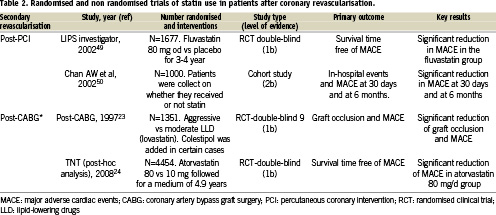

Following CABG, lipid-lowering drugs have been demonstrated to prevent both native coronary artery and graft atherosclerosis progression, as well as decreasing subsequent cardiovascular events22. On these grounds, recent trials reported a better clinical outcome when an aggressive LDL-cholesterol-lowering treatment is followed and this benefit is linked to the development of less new stenoses, either native coronary or saphenous vein graft. Two large RCT´s were specifically designed to test the use of statins after CABG, the Post-CABG trial (Post-Coronary Artery Bypass Graft) and TNT trial (Treating to New Targets) trial post-hoc analysis24 (Table 2). The former randomised 1,351 patients with patent venous bypass grafts to 40 or 2.5 mg/day of lovastatin. After a 4.3-year follow-up, graft attrition, assessed angiographically, occurred less frequently in the aggressive treatment arm. This finding paralleled the lower adverse event rate documented in the same arm. The latter, the TNT trial post-hoc trial, analysed data obtained in those 4,454 out of the total 10,001 patients included in the trial with prior CABG and LDL levels < 130 mg/dl. This subgroup of patients had been randomised to atorvastatin 80 (aggressive therapy) or 10 mg (less-aggressive therapy), and followed during an average of 4.9 years. In both trials, aggressive statin treatment was superior to a low-dose regimen in decreasing both graft atherosclerosis progression and need of secondary revascularisation (either with redo CABG or PCI). This benefit was independent of gender, age, and presence of risk factors for coronary heart disease, including smoking, hypertension, diabetes, or elevated serum triglyceride concentrations23,24.

There is limited evidence of specific benefit of ACE inhibitor and beta-blocker treatment in patients with prior revascularisation. The QUO VADIS study (Quinapril on clinical outcome after coronary artery bypass grafting), which included 149 patients with prior surgical revascularisation, evaluated the benefit of quinapril on total exercise endurance one year after the onset of treatment25. Although the primary endpoint was not reached, patients allocated to quinapril experienced significantly less adverse cardiovascular events. The ONTARGET trial (ONgoing Telmisartan Alone and in combination with Ramipril Global End-point Trial) evaluated the hypothesis that complete inhibition of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in patients with high cardiovascular risk profile is superior to partial inhibition26. The trial randomised more than 26,000 patients with normal left ventricular ejection fraction to telmisartan 80 mg, ramipril 10 mg or both treatment arms. Around 30% of the patients had previous coronary revascularisation. Telmisartan was found equivalent to ramipril, but the combination of both caused more adverse events without showing additional benefits. On the other hand, few controlled trials have tested the effect of beta-blockers after CABG. Sjoland H et al reported on the effect of beta-blockers on a surrogate endpoint (exercise capacity) after CABG in 967 patients randomised to active treatment or placebo27. No benefit associated with treatment was observed in terms of exercise capacity or clinical outcome. Since few RCT`s have either been done or performed sub-group analysis to evaluate ACE-inhibitor and beta-blocker treatment after coronary revascularisation, a evidence-based recommendation cannot be issued.

In summary, antiplatelet agents and statins have convincingly demonstrated clinical benefit after CABG. Antiplatelets prevent graft thrombosis during the first year after surgery and statins reduce the graft atherosclerosis progression as well as subsequent clinical events. There is little evidence to support routine use of ACE-inhibitors and beta-blockers in post-CABG patients, but both must be systematically indicated in those patients with prior MI, left ventricular dysfunction or congestive heart failure.

Importance of secondary prevention after percutaneous revascularisation

Percutaneous coronary intervention improves epicardial vessel haemodynamics by dilating stenosed segments, but does not provide protection against pathobiological changes in the other atheromatous segments which may cause plaque ulceration, thrombosis or luminal narrowing due to plaque progression26. Furthermore, vascular responses to endovascular treatment stand behind the development of restenosis, an important limitation of this treatment in the long-term. Even after the introduction of drug eluting stents (DES), a major breakthrough in controlling its appearance after stent implantation, restenosis continues being a major problem for patients, clinicians and health care systems28. The large number of PCIs performed worldwide and expanded off-label, real-life stent use – with higher restenosis rates than those reported in the controlled environment of clinical trials – ensures that restenosis will continue to be the main reason for secondary revascularisation for years to come.

Several considerations must be made regarding secondary prevention after PCI and we shall focus first on its impact on the prevention of cardiovascular events and atherosclerosis progression. While PCI can be performed with the aim of improving prognosis or controlling anginal symptoms, the latter constitutes its most common indication. This is probably one of the reasons that multiple clinical trials comparing medical therapy and PCI failed to demonstrate a clear benefit in terms of reduction of death or myocardial infarction29. However, Jaber et al performed a retrospective cohort study of PCI procedures involving 7,745 patients demonstrating that after successful PCI, the use of multiple evidence-based classes of cardiovascular medications was associated with improved outcome of death or MI30. On these grounds, The COURAGE trial (Clinical Outcomes Utilization Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation) was designed to determine whether PCI coupled with optimal medical therapy reduces the risk of death and nonfatal myocardial infarction in patients with stable coronary artery disease, as compared with optimal medical therapy alone31. Involving a total of 3,071 patients with coronary artery disease (25% with prior revascularisation by CABG or PCI), patients allocated to optimal medical therapy alone were found to present a similar risk of adverse major cardiovascular events than those allocated to PCI as initial management strategy.

The COURAGE trial was fraught by serious bias problems: eligibility criteria was fulfilled by less than 10% of patients undergoing assessment for their inclusion of the study, and the average inclusion per centre was less than 50 patients per year during the five year enrolment period31. The most likely result of such bias is that patients in the PCI arm presented a far lower risk than those treated in everyday practice. In addition, it might be unfair not to mention that the application of optimal secondary preventive measures in the study population, enforced to a higher level than that reported in real-life registries, did not play an important role in equalising major cardiac events in both groups. However, freedom from angina in patients in the medical group may reflect a benefit of both antianginal medications (e.g., nitrates and beta blockers) and secondary prevention therapies (statins) due to their effect on pathobiological processes such as endothelial dysfunction.

The other aspect that requires a separate discussion is whether secondary prevention plays a role in the prevention of restenosis at the treated coronary segment. The rationale behind the development of DES, namely that local delivery of antiproliferative drugs targets selectively the segment to treat, avoiding systemic administration of drugs, has proved extremely successful. However, multiple studies were performed in the pre-DES era testing the efficacy of different drugs on preventing restenosis, including the four pharmacological groups that constitute the cornerstone of secondary prevention: antiplatelet agents, statins, ACE inhibitors and beta blockers32-38. None of these drugs demonstrated a preventive effect in this regard. However, it is important that some of the studies performed, like the FLARE trial (FLuvastatin Angiography REstenosis)9 demonstrated an important reduction in major cardiac events in the treatment arm. This contributed to highlight the particularly high cardiovascular risk of patients requiring coronary interventions, and the distinct benefit of adequate preventive treatment (Figure 1). A separate discussion would be required for diabetes mellitus, a strong predictor of coronary restenosis and a critical risk factor for the occurrence of major cardiac events. Although it is beyond the scope of this article, glycemic control appears of paramount importance, although no specific RCTs have been performed for the prevention of restenosis besides the already mentioned PERISCOPE trial14, which was discussed above.

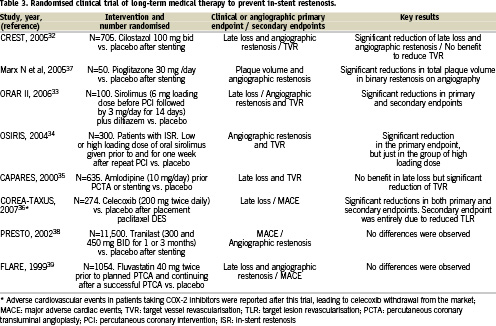

Antiplatelet agents constitute a key aspect of co-adjuvant treatment in PCI, and therefore we would not discuss them as a separate issue, nor will we perform a review of the topic which would be beyond the scope of the present article. But before finishing this section, we should mention several recent pharmacologic approaches, which, although shadowed by the overwhelming success of DES, might constitute alternative, or co-adjuvant approaches to prevent in-stent restenosis, particularly since some of them have other medical applications, including the control of diabetes. Table 3 provides a list of such agents, CRT´s and the most relevant features. It should be kept in mind, however, that these CRT´s did not perform a comparison with DES. Besides, the reduction in late luminal loss observed in the treatment arm is significantly lower than that achieved with DES. For instance, in the CREST trial testing cilostazol, late lumen loss in the treatment arm was higher than that reported in DES trials (0.57 mm in CREST versus 0.24 mm in SIRIUS or 0.23 mm in TAXUS IV)32,40,41. More late luminal loss was also noted with oral sirolimus in ORAR II33 compared to a sirolimus-eluting stent in SIRIUS (0.66 mm versus 0.24 mm), but significant systemic side effects limited its being approved for restenosis prevention, other than perhaps in patients receiving a stent and being treated with this drug after renal transplant.

Implementation of secondary preventive treatment after coronary interventions in the real world

Although the importance of secondary prevention in patients with coronary artery disease has been widely disseminated among health care professionals, management of these patients remains far from ideal (Table 1). While large coordinated national and international secondary prevention programs are necessary, the contribution of the individual physician is of vital importance for enforcement of secondary prevention in everyday practice. With regard to the main issue of this article, prevention in patients with repeated coronary interventions, we should consider potential weaknesses and threats limiting the application of secondary preventive measures in these patients.

The first of these obstacles would be the limited information available on secondary prevention in patients with coronary interventions and, even more, in those with repeated interventions. Available knowledge is derived from CRTs, but few of them considered this important patient subgroup in a pre-specified way during trial design. The second aspect, not fully independent from the previous one, is the promotion of physician awareness about the distinct role of secondary prevention after coronary intervention. Dissemination of the information collected in clinical trials appears an important task, as also would be the inclusion of this missing category in clinical practice guidelines, as discussed in the first chapter of this issue: a recognisable heading under which a multiplicity of relevant topics are grouped and presented in a coherent manner. Treating cardiovascular disease as a health care process, avoiding episodic health care, has been recommended in consensus documents and certainly would facilitate a closer patient follow-up, ensuring compliance with secondary preventive treatment42.