Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is a treatment reserved for elderly and frail patients. Although the evidence base now extends to intermediate-risk patients (however you define risk!), the reality is that this technology continues to be used almost exclusively in the elderly. This theme is consistent among the randomised trials that have extended the indications for TAVI from extreme to intermediate risk: the average age of the PARTNER (1A, 1B, and 2) and CoreValve US Pivotal studies is 83 years1-3. Even the NOTION trial that evaluated TAVI in low-risk patients (Society of Thoracic Surgeons [STS] score: 2.9±1.6%) had an average age of 79 years4. The recruitment of such elderly patients in these clinical trials was necessary to achieve the strict inclusion criteria historically centred on surgical risk scores (STS or EuroSCORE). The use of surgical scores to determine risk in a patient population distinct from that from which it was derived and undergoing a transcatheter rather than surgical procedure is now widely accepted to be illogical5. As such, the institutional Heart Team is now the dominant mechanism to determine risk in ongoing low-risk trials (PARTNER 3 [NCT02675114] and CoreValve Low Risk [NCT02701283]) and in clinical practice guidelines6.

Early comparisons between TAVI and surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) suggested similar one-year rates of death and stroke (PARTNER 1A, CoreValve US Pivotal)1-3,7. Transcatheter procedures were, however, associated with higher rates of new permanent pacemaker, vascular complications, paravalvular leak, and were more expensive. On the other hand, those undergoing surgery had longer ICU and hospital stay, higher rates of acute kidney injury, atrial fibrillation, bleeding, blood transfusion, and worse quality of life for the first year. Iterative device development, operator experience, and the integration of multislice computed tomography for procedural planning have addressed many of the drawbacks of early TAVI: transfemoral TAVI is now associated with lower mortality than surgery and the rates of both vascular complications and paravalvular leak have been reduced to surgical levels8. Transfemoral TAVI has become more cost-effective than SAVR. Why then, with these advantages, does TAVI remain a treatment for elderly and frail patients?

The answer is obvious: younger patients have lower STS scores (80% of patients undergoing SAVR are at low operative risk with an STS score of <4%9) and the technology needs to be proven in this population. But, do we really expect the results of TAVI to be less favourable in younger patients? The lower the risk, the better TAVI seems to perform. It is not therefore an expectation of higher rates of death, stroke, PVL, etc., that has limited the expansion of the technology to younger patients. Rather, the primary reason that TAVI continues to be a treatment for the elderly is the absence of studies that demonstrate long-term durability! Our surgical colleagues have clearly illustrated durability for their bioprosthetic valves, right? Well, although one would expect the surgical literature to be replete with high-quality longitudinal studies describing decades of bioprosthetic valve performance, these data simply do not exist. There are no large long-term independent core laboratory-adjudicated serial echocardiographic surveillance studies on surgical bioprosthetic valve performance. The often cited reports of surgical bioprosthesis durability of 15-20 years emanate from single-centre experiences of modest size10.

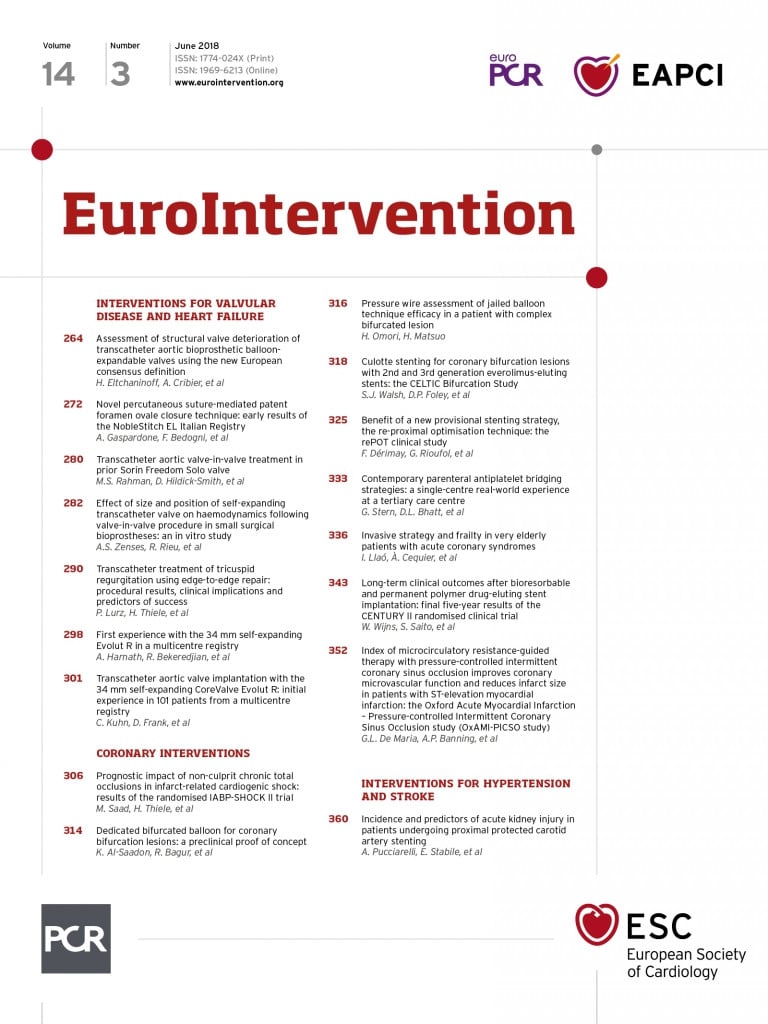

Although imperfect, such studies do provide a “guesstimate” of longer-term valve performance. It is therefore encouraging to see some early snapshots of TAVI durability starting to emerge. In the current issue of EuroIntervention, the pioneers of TAVI from Rouen, France, report the medium-/long-term durability of balloon-expandable transcatheter aortic valves11. Importantly, this report adjudicates valve performance/durability according to the recently published consensus document from the European Association of Percutaneous Coronary Interventions12. In this study, Eltchaninoff et al report the eight-year incidence of structural valve deterioration and bioprosthetic valve failure to be 3.2% (95% CI: 1.45-6.11) and 0.58% (95% CI: 0.15-2.75), respectively. These data are in direct contradistinction to an abstract presented at EuroPCR 2016 that included data from Rouen, and reported a Kaplan-Meier estimate for the eight-year rate of structural valve degeneration of 50% (Dvir D. First look at long-term durability of transcatheter heart valves: assessment of valve function up to 10 years after implantation. Presented at: EuroPCR 2016, Paris, France). The importance of the development of standardised definitions for reporting valve failure/degeneration is clearly emphasised by these dichotomous results.

The intervention and surgical communities and, more importantly, our patients need to understand the true long-term incidence of bioprosthetic valve failure. At EuroPCR 2018, EuroIntervention Deputy Editor Lars Søndergaard presented six-year haemodynamic data from the randomised NOTION 1 trial: effective orifice area was larger with TAVI than SAVR (1.53 vs. 1.16 cm2, p<0.001) and mean gradient was lower (9.9 vs. 14.7 mmHg; p<0.001) (Søndergaard L. NOTION: longevity of transcatheter and surgical bioprosthetic aortic valves in patients with severe aortic stenosis and lower surgical risk. Presented at: EuroPCR 2018, Paris, France). Furthermore, structural valve deterioration (mean gradient ≥20 mmHg; change in mean gradient ≥10 mmHg from baseline; or moderate/severe intraprosthetic aortic regurgitation [new or worsening from baseline]) was significantly less common with TAVI than SAVR (4.8% vs. 24.0%; p<0.001). Only with this kind of information can we help our patients to make informed treatment decisions. The ongoing low-risk industry-sponsored trials are unlikely to provide answers to the durability conundrum: the sample sizes are perhaps too small for longitudinal analyses and the follow-up period is only 10 years. Even really poor surgical bioprosthetic valves made it to eight years! There is an absolute requirement for large prospective registries with core laboratory adjudication of serial echocardiographic examinations for both surgical and transcatheter bioprostheses.

Transcatheter valve durability is not the sole determinant of extending TAVI to younger patients (coronary access, impact of long-term right ventricular pacing, cost-effectiveness, reimbursement), but it is the most important. Demonstrating equivalence, inferiority, or superiority to current-generation surgical bioprostheses will take time. In the meantime, the ongoing low-risk studies will probably support TAVI in lower-risk patients, but what about younger patients? Only the NOTION 2 trial (NCT02825134) has an upper age limit (≤75 years old) ensuring the recruitment of younger patients. So, in 10 years, will we be routinely treating patients in their sixth decade with TAVI? Probably, but, until then, TAVI will continue to be a treatment for the elderly and frail.