Abstract

Aims: In a rabbit denudation model, assess impact of strut thickness on arterial healing by comparing endothelial cell coverage and strut tissue coverage after implantation of bare metal stents of varying thickness; evaluate the effect of an everolimus-eluting stent.

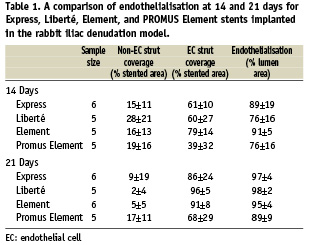

Methods and results: Strut tissue coverage and endothelialisation were assessed 14 and 21 days after implantation with scanning electron microscopy quantitation methods and immunostaining against the endothelial cell marker PECAM-1 (CD-31). At 14 days, strut tissue coverage was higher with the stainless steel Liberté stent (88%, 97 µm) versus Express (77%, 132 µm). The platinum chromium Element stent with the thinnest strut (81 µm) had the highest level (95%). By 21days endothelialisation was complete for all. The everolimus-eluting Element stent had a 1-week delay in luminal endothelialisation but was >89% by 21days; strut endothelial coverage was >79% in 80% (4/5) of animals, with total strut tissue coverage >95%.

Conclusions: This study demonstrated that strut thickness affects strut tissue coverage post stent implantation and the addition of an everolimus-eluting polymer introduces a short delay in endothelialisation. The results highlight the need to control for aspects of stent design such as strut thickness when comparing across drug-eluting stent platforms.

Introduction

Clinical trials of first generation coronary drug-eluting stents (DES) have demonstrated reduced rates of restenosis compared to bare metal stent controls1-5 with no increases in death or myocardial infarction.6 However, autopsy data suggest that uncovered struts may play a role in some late stent thrombosis events observed clinically.7,8 Typical safety evaluations of coronary stents include scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of the luminal flow surface of stented vessels 30, 90, and 180 days after stent implantation, most often in the non-injured porcine coronary model.9-11 In the porcine model complete endothelialisation is commonly observed at 30 days post-stent implantation for marketed DES devices, with no differences reported between DES and comparator bare metal stents (BMS) at the time points evaluated.12-15 Even when evaluated at earlier time points, the porcine model does not allow for discrimination between bare and DES devices.11 In contrast, the rabbit iliac model with balloon denudation of the endothelial cell layer promotes delayed arterial healing kinetics, allowing for better discrimination between device types at early time points (14-21 days). Joner et al recently published results in this model showing delays in strut tissue coverage and endothelial cell coverage with DES compared to BMS16 and also reported a disparity in re-endothelialisation rates among different comparator DES at 14days. However, the relative contributions of drug coating versus stent strut thickness were not apparent due to the nature of the study design. Other studies have implicated stent strut thickness in the kinetics of re-endothelialisation17-19 and this likewise could contribute to some of the results observed in the Joner study.

The purpose of the current study was to determine the impact of stent strut thickness on the rate of re-endothelialisation following implant of three different BMS (Express™, Liberté™, and Element™; Boston Scientific Corporation [BSC], Natick, MA, USA) in the rabbit denudation model. These three stent types represent an evolution of platform design and architecture from the thickest, 132 µm stainless steel Express to the thinnest, 81 µm Element stent manufactured from a novel platinum chromium alloy.20 Additionally, the effect on endothelialisation and strut coverage of an everolimus-eluting coating on the Element stent platform (PROMUS Element) was examined.

Methods

Device descriptions

The three BMS assessed in this study included the balloon-expandable Express™ (132 µm strut thickness; 71-91 µm strut width) and Liberté™ (97 µm strut thickness; 76 µm strut width) stainless steel stents and the Element™ stent made of a platinum chromium alloy (81 µm strut thickness; 66 µm strut width). Along with differences in strut thickness and width, stent architecture varied among the three BMS.21 Also examined was PROMUS™ Element, which contains the antiproliferative agent everolimus22 applied to the Element stent using the same combination of polymer layers found in the PROMUS everolimus-eluting stent.4 All stents were 2.75 mm in diameter and 16 mm long, with the exception of initial tests with 8 mm long Express stents for method development. All stents were manufactured by BSC, Natick, MA, USA.

Animal care and use

Study protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at American Preclinical Services (Minneapolis, MN, USA), and experiments were conducted according to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (U.S. National Institutes of Health Publication 85-23, revised 1996).

Anesthetised adult female New Zealand White rabbits underwent endothelial denudation of both iliac arteries using an angioplasty balloon catheter (Maverick, 2.25 mm × 15 mm, BSC, Natick, MA, USA). Denudation was achieved by three balloon passes at a balloon to artery ratio of approximately 1.05:1. Immediately following balloon denudation, stents were deployed at a target stent to artery ratio of 1.3:1. Five to six devices of each type were implanted per time point, with each rabbit receiving one stent per iliac artery. Rabbits were maintained on aspirin (40 mg/day, PO) starting 24 hours before catheterisation with continued dosing throughout the in-life phase of the study. In addition, heparin was administered at the time of catheterisation with doses ranging from 20-250 IU/kg to maintain activated clotting times of 250 seconds or above. Following device implantation, post-procedural angiography was performed to verify stent placement and patency and the animals were allowed to recover.

After 7, 14, or 21 days, animals were euthanised and stented arteries were perfused with lactated Ringer’s solution to remove blood and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Stented vessels were bisected longitudinally with one half processed for SEM and the opposite reserved for en face immunostaining of whole mount vessels.

Quantitative analysis of endothelial surface coverage

SEM imaging and quantification was essentially conducted according to the methods of Joner et al.16 Briefly, serial images were acquired at low magnification (15× magnification) and were digitally assembled to provide a view of the entire luminal stent surface area. Enlarged images (200× magnification) were assessed by a trained analyst and endothelial surface coverage was traced and measured with Image Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics Inc, Bethesda, MD, USA) and reported as the percent strut area covered and percent luminal area covered. In addition, areas of stent struts not covered by endothelium were further characterised as being uncovered or covered with a proteinaceous matrix consisting of focal platelet and fibrin aggregates intermixed with red blood cells and inflammatory cells. Stent strut surface area was calculated from high resolution faxitron images.

Whole-mount en face immunostaining for PECAM-1

Immunostaining for PECAM-1 was carried out with modification of the methods of Joner et al.15 Longitudinally bisected vessels were rinsed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and incubated in PBS with Tween 20 (Serotec, Raleigh, NC, USA) containing 10% normal goat serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for onehour at room temperature. Following the blocking step, vessels were incubated with a primary antibody against PECAM-1 (anti-PECAM-1, 1:10 dilution; Dako, Carpintaria, CA, USA) overnight at 4°C. Specific binding was visualised with goat anti-mouse antibody labelled with Alexa Fluor 594,1:200 dilution (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in the dark, for one hour at room temperature.

Confocal images were acquired via fast mode scanning with a 20x water immersion lens on an Olympus Fluoview 1000, BX61 with a Proscan Prior Automatic Stage (FV.AS.10 Software) at the Biomedical Imaging Processing Lab at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA. Fluorescent images were overlaid and photo-merged with differential interference contrast (DIC) images to denote the pattern of endothelial cell coverage over stent struts.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation. For quantitative SEM data,analysis of variance was used to make comparisonsacross allgroups. Individual comparisonsbetween groups were made using the Tukey pairwise comparison test. P values of < 0.05were consideredstatistically significant.

Results

Kinetics and pattern of re-endothelialisation following bare metal stenting

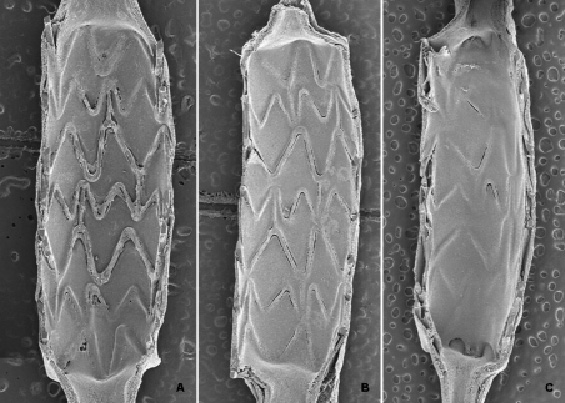

A preliminary study to determine the appropriate time points for evaluation of endothelialisation following balloon-denudation and stenting in the rabbit iliac artery was conducted using Express BMS at follow-up times of 0, 7, 14, 21 and 28 days, with sample sizes of 5-6 stented vessels per time point. Immediately post-deployment (0days), 89±15% of the luminal surface area was determined to be free of endothelial cells via SEM visualisation. At seven days post-deployment, 88.3±5.0% of the luminal area was covered by endothelial cells and coverage was complete at 14 days (97.8±3.6%), 21 days (99.5±0.7%), and 28 days (100%±0%). Endothelialisation followed a distinct pattern, progressing from the proximal and distal ends of the stent towards the middle (Figure 1). An additional study was conducted looking at the impact of device length at time points of 7, 14 and 21 days (data not shown). Based on this analysis, follow-up time points of 14 and 21 days were selected for further analysis. Additionally, the stent length evaluated was increased from 8mm to 16mm so as to further delay the rate of endothelialisation and allow for greater discrimination between stent platforms.

Figure 1. Pattern of re-endothelialisation following stenting. Stenting of denuded rabbit iliac arteries with bare metal stents follows a predictable pattern and time course, with re-endothelialisation progressing from the proximal and distal ends towards the middle (A-C). By seven days post implant 88.3%±5.0% of the luminal surface area is re-endothelialised (A), with complete endothelialisation by 14 (97.8%±3.6% , B) and 21 days post-implant (99.5%±0.7%, C).

Quantitative SEM comparisons across bare metal stent platforms

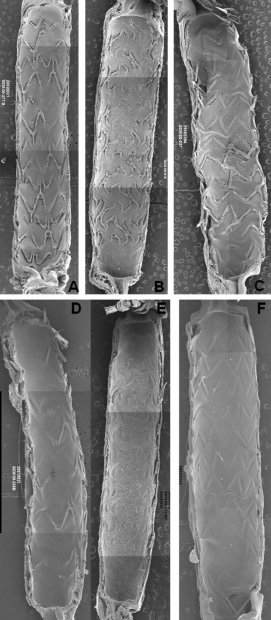

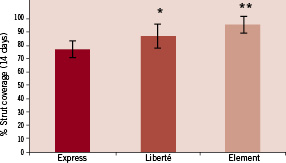

At 14days, the luminal surface area was incompletely endothelialised for Express and Liberté but nearly complete for Element (Figure 2, A-C and Table 1). By 21 days endothelialisation of luminal surface area and stent struts was largely complete for all three (Figure 2, D-F and Table 1). Overall strut tissue coverage, including endothelial cell coverage plus non-endothelial cell coverage (focal platelet and fibrin aggregates intermixed with red blood cells and inflammatory cells) was significantly lower at 14days with the thicker Express struts (77%) compared to Liberté (88%, P=0.05) and Element (95%, P=0.001) (Figure 3). At 14days coverage by tissue and cell types other than endothelial cells was 15% for Express, 28% for Liberté, and 16% for Element (Table 1). By 21days coverage was almost completely due to endothelial cells as non-endothelium accounted for 9%, 2%, and 5% of coverage with Express, Liberté, and Element, respectively.

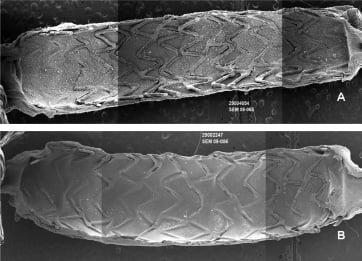

Figure 2. Scanning electron micrograph images post-implant in denuded rabbit iliac arteries. Images are representative examples of bare metal Express (A, D), bare metal Liberté (B, E) and bare metal Element (C, F) stents at 14 days (A-C) or 21 days (D-F).

Figure 3. Effect of strut thickness on the kinetics of tissue coverage. At 14 days post-implant, 77±6% of bare metal Express stents struts had some form of tissue coverage compared to 88±7% of bare Liberté (* P=0.05) and 95±4% of bare Element (** P=0.001) stent struts.

Quantitative SEM comparison between Element and PROMUS Element stents

At 14days, endothelialisation of the luminal surface area was lower with PROMUS Element compared to Element but was nearly complete for both by 21 days (Figure 4and Table 1). However, in the PROMUS Element cohort, stent struts remained incompletely endothelialised even at 21 days (68±29%, Table 1). This was largely due to a single animal with poor strut endothelial cell coverage (19% compared to >79% for the remaining four animals in the cohort) total strut coverage for this animal was also very low, 33%, as compared to >95% for the remaining animals in the cohort. The components of non-endothelial cell stent strut coverage at 21 days with the DES were similar to that observed with the BMS.

Figure 4. Scanning electron micrograph images of PROMUS Element stents. Images are representative examples at 14 days (A) and 21 days (B) post-implant in denuded rabbit iliac arteries.

Comparisons of PECAM-1 staining between Element and PROMUS Element stents

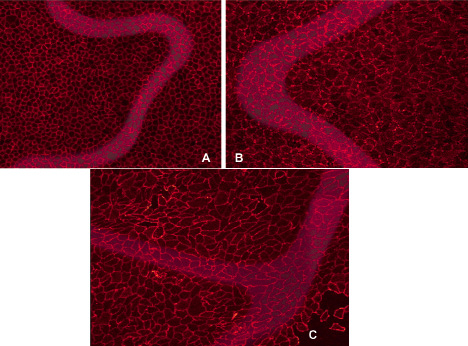

Immunostaining of whole mount en face stented vessels for PECAM-1 demonstrated confluent endothelial cell monolayers as assessed by staining at the circumference of cells, where cell-cell interactions occur. Endothelial cell morphology at 21days was similar across all four stent types (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Representative luminal en face immunohistochemical staining for PECAM-1. Images show the confluent endothelial cell monolayer overlying stented regions of bare Liberté (A), bare Element (B), and PROMUS Element (C) stents 21 days post-implant in the rabbit iliac denudation model.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that strut thickness and drug coating can affect the rate of strut tissue coverage and luminal surface endothelialisation post stent implantation. The animal model used here, balloon denudation of the endothelial cell layer in rabbit iliac arteries, promotes delayed arterial healing kinetics, allowing for better discrimination in stent strut tissue coverage and endothelialisation between device types. At 14 days, strut tissue coverage as determined by SEM was significantly greater with the thinner bare metal stainless steel Liberté strut (88%) compared to the thicker Express (77%, P=0.02). The platinum chromium Element stent with the thinnest strut had the highest level of strut tissue coverage (95%, P=0.001 compared to Express) and the highest level of strut and luminal endothelialisation at 14 days (79 and 97%, P>0.05). By 21days luminal and strut endothelialisation were complete for all three stent platforms. The addition of an everolimus-eluting coating to the Element stent delayed luminal endothelialisation by one week but it reached 89% by 21days with strut endothelial coverage >79% in 80% of animals and total strut coverage >96% in 80% of animals.

In accordance with multiple consensus documents for the evaluation of drug-eluting coronary stents, typical preclinical safety evaluations include SEM analysis of the luminal flow surface of stented vessels 30, 90, and 180 days after stent implantation, most often in the non-injured porcine coronary model.9-11,23 Evaluations of Express, Liberté, Element, and PROMUS Element stents in the porcine model have shown complete luminal endothelial cell coverage by 30 days or earlier.12,13,24 The vascular compatibility of the polymer coating for PROMUS Element, which consists of the same combination of polymer layers found in the PROMUS everolimus-eluting stent4, has also been evaluated previously. In the rabbit model, complete endothelial cell coverage by 14days was reported for stents with polymer-only coating25 while in the pig complete endothelial cell coverage was documented by 30 days.24 However, species and model dependent factors impact the time course of arterial healing following stent implant and some clinical evidence suggests that wide inter-individual variability exists in the human patient population.7,8,12,13,26,27 In the current work, inter-animal variability was evident in the healing of treated arteries. This could be attributed to the natural variation in vascular repair but could also be related to incomplete stent apposition at deployment where the resulting incomplete neointimal coverage of malapposed struts may be a predisposing factor for very late stent thrombosis in patients.28 Optical coherence tomography can provide a high level of accuracy in evaluating heterogeneity of vascular response following stent implantation.29 In both animal models and human clinical outcomes, further study of this variability is warranted. A recent comparison of four DES in the rabbit iliac model concluded that the first generation paclitaxel- and sirolimus-eluting stents delayed arterial healing compared to second generation everolimus- and zotarolimus-eluting stents.16 The results of our study, however, highlight the need to control for aspects of stent design such as strut thickness when conducting quantitative comparisons across DES platforms.

The pattern of re-endothelialisation for the stents tested here appeared to progress from uninjured areas (the proximal and distal segments of the stented vessel) toward areas of injury, with the middle region being the final area to develop complete endothelial cell coverage (Figure 1), as observed by others with this model.30,31 This is further illustrated by the finding that longer stents, and therefore longer regions of denudation, develop complete endothelialisation at a slower rate compared to shorter stents (Figures 1-3).

In this study, both Element and PROMUS Element stents showed nearly complete endothelialisation of the luminal surface area by 21days with strut endothelial coverage >91% for all Element stents and >79% in 80% (4/5) of animals receiving PROMUS Element. These data are similar to the endothelialisation data at 28days reported by Joner et al for the comparison of the XIENCE™ DES (>70% endothelialisation) with Multi-Link Vision™, the equivalent BMS (>90%).16 In addition to SEM evaluation of endothelial cell morphology, immunostaining demonstrated no loss of PECAM-1 expression at cell-cell junctions for PROMUS Element compared to Element. Taken together, these data indicate that the everolimus-eluting coating on PROMUS Element accounts for minimal delayed arterial healing when delivered on thinner strut, lower profile stent platforms. This delay in endothelialisation is not unexpected: as an mTOR inhibitor, everolimus is known to impact endothelial cell growth and function32. It is important to note that this delay in endothelialisation was limited to the rabbit denudation model as there was no delay in endothelialisation associated with PROMUS Element in a standard porcine model22.

Autopsy studies have revealed a correlation between uncovered struts and stent thrombosis7,8,27 which has driven preclinical model development towards species and time points that better predict delayed arterial healing as evidenced by uncovered struts and incomplete endothelialisation following stenting. In the clinic, optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging can provide some assessment of strut coverage after coronary stenting, including the detection and measurement of thin layers of neointimal coverage.29,33,34 Randomised clinical trials using OCT may help ascertain the effectiveness of new generation DES in improving vessel healing and reducing stent thrombosis.

Limitations of this study include, as with all preclinical models, the use of an animal model as a human clinical surrogate. However, the rabbit denudation model promotes delayed arterial healing kinetics allowing for better discrimination between device types and as such may provide a better approximation of the clinical situation than the non-injured swine coronary model often used for safety evaluations of DES. While the major difference between the BMS assessed was strut thickness and strut widths, it should be noted that strut pattern differed and the Element stent was made of a platinum chromium alloy compared to the stainless steel Express and Liberté stents. The significantly greater uncovered strut area observed for Express versus Liberté (P=0.02), however, suggests that strut thickness is the major determining factor in strut coverage and re-endothelialisation.

In conclusion, the current study is the first preclinical evaluation of BMS platforms to determine the impact of strut thickness on the rate of strut tissue coverage and endothelialisation post coronary stent implantation. Increased strut thickness was shown to reduce the rate of strut coverage and the addition of an everolimus-eluting polymer introduced a short delay in luminal endothelialisation. The results highlight the need to control for aspects of stent design such as strut thickness when comparing across BMS and DES platforms.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Prof. Willem J. van der Giessen, MD, PhD and Heleen van Beusekom, PhD of the the Department of Cardiology, Erasmus Medical Center (Rotterdam, The Netherlands) for their critical review of this manuscript and Jerry Sedgewick, PhD of the Biomedical Imaging Processing Lab at the University of Minnesota, (Minneapolis, MN, USA) for his technical assistance with confocal image acquisition and processing. Additionally the authors thank Natalia Sushkova, MD for her technical assistance with development of the whole mount en face immunostaining procedure; Alisa Davis for SEM image acquisition; Bill Stoffregen, DVM, PhD for his training and oversight of the SEM image analysis; and Ruth M. Starzyk, PhD for her assistance with drafting and editing the manuscript (all of Boston Scientific Corporation).