The HYPEREMIC trial by Elghamaz et al1 describes the use of a 3 Fr over-the-wire microcatheter for inducing maximal coronary hyperaemia during fractional flow reserve (FFR) measurement.

Forty-one patients sequentially received intravenous and intracoronary adenosine in a randomly alternated order. The data indicate that intracoronary administration of adenosine through the microcatheter allows a total dose reduction of two magnitudes and makes it possible to reach maximal hyperaemia in half the time compared to conventional intravenous administration. Patient discomfort is also markedly reduced when the intracoronary route is used. The authors do not provide analysis data about test-retest variability but suggest that measuring FFR by this means of hyperaemia induction is comparable to conventional intravenous administration of adenosine.

FFR expresses to what extent a stenosis limits maximal achievable blood flow, as compared to if the stenosis were absent. Accordingly, maximal, stable (steady-state) hyperaemia underpins the basic concept of FFR. An ideal coronary vasodilator should provide highly reproducible maximal hyperaemia quickly after its administration, with a steady state of at least 30 seconds, and should not change systemic haemodynamics. In addition, the ideal vasodilator should be cheap, widely available and without side effects. Not surprisingly, such a drug has not yet been identified.

The most commonly applied method of achieving hyperaemia is probably the intracoronary bolus injection of adenosine. Very simple, barely disruptive of regular practice, with very few side effects, this remains the simplest way to obtain a “stationary” FFR value associated with an intermediate focal stenosis. However, given the extremely short half-life of adenosine that is quickly deaminated by the red blood cells, its hyperaemic plateau does not last longer than 10-15 seconds2, too short to allow more sophisticated explorations into coronary physiology.

There is a growing interest in identifying coronary pathologies beyond simply the presence or absence of a focal coronary stenosis. The recently introduced pullback pressure gradient (PPG) index allows quantifying the distribution – diffuse versus focal – of epicardial resistance along the epicardial artery3. Likewise, the index of microcirculatory resistance (IMR) aims specifically at quantifying microcirculatory function4. Both metrics need steady-state hyperaemia of at least 30 seconds, and therefore the use of an intracoronary bolus of adenosine is not well suited to these measurements.

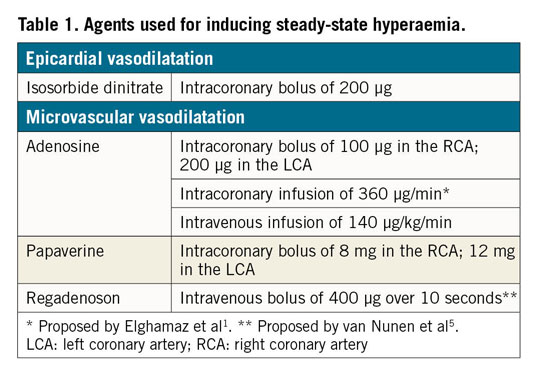

There are, however, a couple of alternatives that have been available for some time now (Table 1). Intravenous administration of adenosine is often regarded as the gold standard for inducing hyperaemia. Intravenous adenosine provides reliable maximal hyperaemia as long as the infusion is running, giving ample time to obtain both the PPG index and the IMR. However, the need for a large (preferably central) venous line, the long delay before reaching steady-state hyperaemia, the haemodynamic fluctuations, as well as occasional patient discomfort, are perceived to be obstacles in many catheterisation laboratories. The use of intravenous regadenoson for inducing coronary hyperaemia has recently been described. Its main (and probably only) advantage is that it may be given as a bolus through an intravenous line, but this is offset by side effects which it has in common with intravenous adenosine, and by the highly variable and unpredictable duration of action5. The view in the past of intracoronary papaverine as the “ideal vasodilator”6 was later overshadowed by an alleged risk of ventricular arrhythmias. Yet, its ease of use, a very limited effect on systemic haemodynamics, and steady-state hyperaemia of 30 to 40 seconds, explain the revival of this very cheap hyperaemic agent. On top of allowing accurate measurements of FFR, it also makes it possible to obtain measurements of the PPG, and to obtain the three consecutive bolus-thermodilution curves needed to calculate the IMR. Importantly, use of papaverine is safe, as long as it is not mixed with contrast medium or with heparin, which would result in precipitation, a probable cause of the previously observed ventricular arrhythmias.

By proposing a dedicated intracoronary infusion catheter to administer adenosine, Elghamaz et al remind us that inducing steady-state hyperaemia is important. The principle, however, is not new. More than 10 years ago, Yoon et al proposed intracoronary infusion through a microcatheter advanced next to the wire7. More recently, a dedicated coronary perfusion catheter was developed for the same purpose, with the additional advantage of being monorail and markedly thinner8. Its lateral holes facilitate steady-state hyperaemia simply through the continuous infusion of plain saline at 15 to 20 mL/min in the first millimetres of the artery of interest9. The mechanism of this hyperaemic phenomenon involving crosstalk between the epicardial segment and its dependent microvasculature is not yet completely understood.

Given the extremely complex and “multilayered” mechanisms controlling myocardial perfusion, it remains astonishing how many pharmacological or mechanical stimuli can induce maximal or near-maximal hyperaemia. To minimise variability related to human factors, each laboratory should master one – or maybe two – of these techniques: due to its simplicity, the intracoronary bolus of adenosine may remain the most widely used method to induce hyperaemia for straightforward FFR measurements. However, more detailed investigation of the epicardial and the microvascular pathologies should be included in the diagnostic arsenal, and therefore finding a handy tool for inducing prolonged steady-state maximal hyperaemia is also becoming of the utmost importance.

Finally, the choice of technique for hyperaemia induction will depend on many factors. One of them appears more and more to be the need for a stable, prolonged steady-state hyperaemic response.

Conflict of interest statement

G. Toth has received research grants from Boston Scientific, Terumo and Abbott Vascular, and consultancy fees from Abbott Vascular, Biotronik and Medtronic. B. De Bruyne has received consultancy fees from Boston Scientific, St. Jude Medical, and Opsens.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.