Primary percutaneous coronary intervention is the preferred method of reperfusion in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). These patients often have multivessel coronary artery disease (CAD), which carries a much worse prognosis than patients with single-vessel disease. Recently, the COMPLETE trial definitively established the benefit of a complete revascularisation strategy in patients with STEMI and multivessel CAD1. At a median follow-up of three years, complete revascularisation reduced cardiovascular (CV) death or new myocardial infarction (MI) by 26% compared with the culprit lesion-only strategy (hazard ratio 0.74, 95% CI: 0.60-0.91; p=0.004). In COMPLETE, as in several other trials2,3, an angiography-guided strategy was used to identify suitable non-culprit lesions for PCI, mainly because of its simplicity and broad applicability. Despite the success of this strategy in guiding non-culprit PCI, this approach could be considered overly inclusive and may select some patients who do not require PCI. Also, visual stenosis severity judged by operators correlates poorly with quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) values measured in an angiographic core lab. A physiology-guided approach addresses these issues by considering not only the degree of stenosis but also the functional significance of the lesion. The use of a physiology-guided approach has demonstrated value in the setting of stable CAD by reducing the number of PCI procedures and ensuing complications (mainly periprocedural MI) and costs4,5,6. Whereas the use of a physiology-guided strategy for PCI is well established in patients with stable CAD, its role in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is much less clear. A recent meta-analysis compared the use of fractional flow reserve (FFR) in ACS versus stable CAD and found that a deferral of either the culprit or non-culprit lesion for PCI on the basis of a non-ischaemic FFR in ACS patients was associated with higher incidence of major adverse CV events compared with stable CAD patients (17.6% vs 7.3%, p=0.004)7. Second, another concern of the physiology-guided strategy is that it cannot account for the impact of plaque morphology on future events. A lesion that is deemed not functionally significant by physiology could still harbour high-risk morphologic features (such as thin-capped fibroatheroma) at increased risk of plaque rupture or erosion leading to future cardiovascular events8,9. The potential benefit of an FFR-guided strategy may be attenuated by deferring intervention on such lesions. In two recent trials evaluating an FFR-guided versus an angiography-guided non-culprit lesion strategy, there were clear reductions in revascularisation, but no apparent reductions in hard endpoints, although neither trial was powered for this outcome10,11. Third, physiology-based methods are invasive in that pressure wires are used to cross the lesion.

Quantitative flow ratio (QFR) is an emerging novel strategy; it is an adenosine-free and non-invasive method to evaluate the severity of lesions. It is calculated by applying computational fluid dynamics to a three-dimensional QCA derived from two angiographic projections separated by at least 25 degrees12. QFR measurement strongly depends on the quality of imaging acquisition. Since it is an angiography-based method for quantifying FFR, the cut-off values are the same as those for FFR, i.e., a value of ≤0.8 is functionally significant. QFR has good agreement with invasive FFR in patients with stable coronary disease. A meta-analysis of the diagnostic performance of QFR with respect to FFR involving prospectively enrolled patients found sensitivity of 84% (95% CI: 77-90, I2= 70), specificity of 88% (95% CI: 84-91, I2= 60), positive predictive value of 80% (95% CI: 76-85, I2= 33), and negative predictive value of 95% (95% CI: 93-96, I2= 76)13. However, the role of QFR may be limited by anatomic and technical factors. For example, its use in evaluating lesions in overlapping and tortuous vessels, bifurcation and ostial lesions may be limited. Factors such as inadequate contrast opacification of vessels and image quality can also affect QFR analysis significantly. Outcome studies evaluating its use are also lacking.

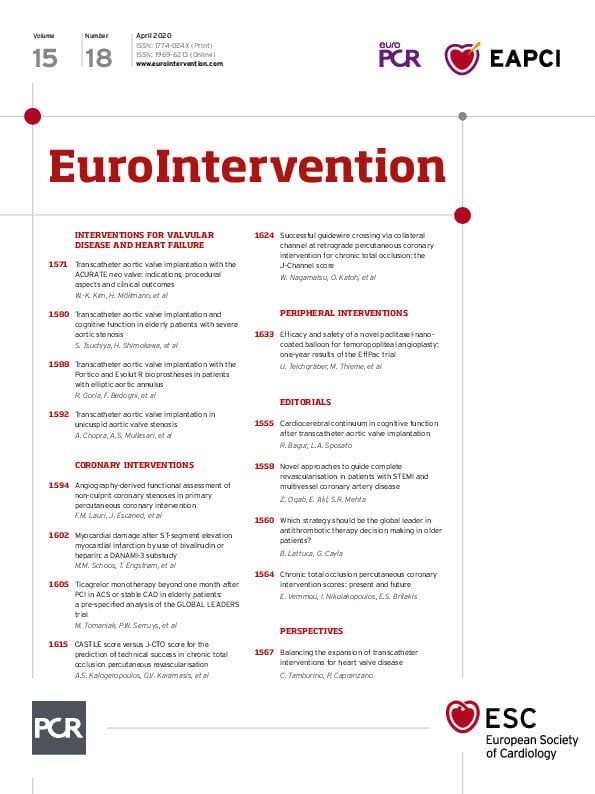

In this edition of EuroIntervention, Lauri et al report the results of their retrospective multicentre study evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of QFR in functional assessment of non-culprit lesions in STEMI patients with multivessel disease (MVD)13

A total of 82 patients were analysed. QFR was performed using the coronary angiogram during primary PCI and its diagnostic performance was compared with that of a matched control group of stable angina patients using FFR as the reference standard. QFR analysis was blinded to FFR. The diagnostic performance of QFR to detect FFR-positive lesions was high (sensitivity 85.7%, area under the curve [AUC] 0.91 [95% CI: 0.85-0.97]) and similar to that observed in the matched control population. The accuracy of QFR was higher for lesions with FFR values outside the grey zone (0.75-0.85), where there was more than 95% agreement between QFR and FFR. The study has several strengths, not least of which is that all QFR assessments were blinded. However, the study also has several limitations. Due to its retrospective analysis, there may be selection bias as the authors excluded about 40% of angiograms. This high rate of exclusion raises two concerns. First, it questions the broad applicability that QFR may have in this setting. Second, it probably overestimated the reported diagnostic accuracy of QFR.

With complete revascularisation in STEMI patients with MVD now becoming the goal across the world, a simple and accurate tool to assess non-culprit lesions for PCI non-invasively may have a significant role. Such techniques hold promise for reducing the number of non-culprit lesion PCI procedures, thereby improving safety and lowering healthcare costs. However, before it can be widely recommended, well-designed and adequately powered prospective randomised trials and large-scale validation studies of this approach in patients with STEMI and multivessel CAD are needed.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.