Abstract

Aims: We examined what type of STEMI patients are more likely to undergo multivessel PCI (MPCI) in a “real-world” setting and whether MPCI leads to worse or better outcomes compared with single-vessel PCI (SPCI) after stratifying patients by risk.

Methods and results: Among STEMI patients enrolled in the Swiss AMIS Plus registry between 2005 and 2012 (n=12,000), 4,941 were identified with multivessel disease. We then stratified patients based on MPCI use and their risk. High-risk patients were identified a priori as those with: 1) left main (LM) involvement (lesions, n=263); 2) out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; or 3) Killip class III/IV. Logistic regression models examined for predictors of MPCI use and the association between MPCI and in-hospital mortality. Three thousand eight hundred and thirty-three (77.6%) patients underwent SPCI and 1,108 (22.4%) underwent MPCI. Rates of MPCI were greater among high-risk patients for each of the three categories: 8.6% vs. 5.9% for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (p<0.01); 12.3% vs. 6.2% for Killip III/IV (p<0.001); and 14.5% vs. 2.7% for LM involvement (p<0.001). Overall, in-hospital mortality after MPCI was higher when compared with SPCI (7.3% vs. 4.4%; p<0.001). However, this result was not present when patients were stratified by risk: in-hospital mortality for MPCI vs. SPCI was 2.0% vs. 2.0% (p=1.00) in low-risk patients and 22.2% vs. 21.7% (p=1.00) in high-risk patients.

Conclusions: High-risk patients are more likely to undergo MPCI. Furthermore, MPCI does not appear to be associated with higher mortality after stratifying patients based on their risk.

Introduction

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the preferred treatment option for restoring epicardial flow and myocardial reperfusion of a culprit lesion in patients with STEMI1. However, the vascular process leading to myocardial infarction is frequently not limited to the culprit vessel, as multivessel disease is present in 40-65% of STEMI patients. The presence of multivessel disease is believed to worsen outcomes compared with single-vessel disease2,3 due to dysfunction extending into the non-infarct zone, a combination of stunned and/or hibernating myocardium, and slow flow and endothelial dysfunction in non-culprit vessels4.

Routine use of PCI in additional lesions at the time of STEMI has not been shown to be beneficial in patients with multivessel disease and, in fact, is largely felt to be harmful5,6. Current guidelines suggest that multivessel PCI (MPCI) at the time of STEMI is not beneficial (Class III, level of evidence C) and should be reserved for high-risk patients only1,5,6. A number of prospective and retrospective studies have examined this question specifically7-13, with a recent and comprehensive meta-analysis including over 40,000 STEMI patients suggesting that MPCI should be discouraged14. However, this analysis combined data from studies that used mixed approaches for risk adjustment. This last point is crucial as MPCI is most likely to be done in STEMI patients who are critically ill. With no large clinical trials to guide physicians in this area, the issue remains contentious.

In this context, we used the Swiss AMIS Plus registry to understand better what types of STEMI patients with multivessel disease are undergoing MPCI in a “real-world” setting, and then to determine whether these patients are more likely to benefit from MPCI versus single-vessel PCI (SPCI) after stratifying patients based on their risk.

Methods

STUDY DESIGN AND STUDY POPULATION

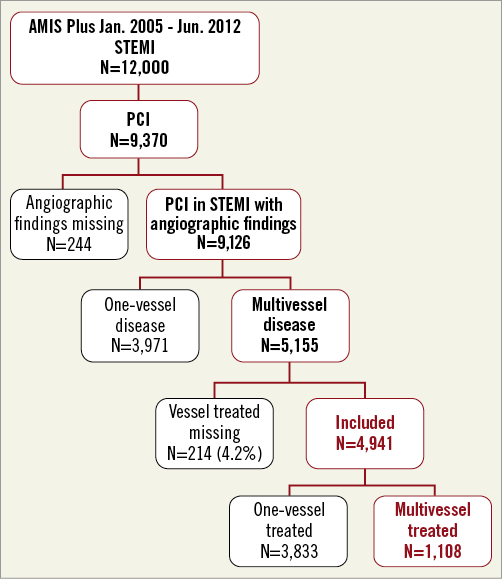

The AMIS (Acute Myocardial Infarction in Switzerland) Plus project founded in 1997 is an ongoing nationwide prospective registry of patients admitted with ACS to hospitals in Switzerland. Details have been previously published15,16. Participating centres, ranging from community institutions to large tertiary facilities, provide blinded data for each patient through standardised internet-based or paper-based questionnaires. These are checked for plausibility and consistency by the AMIS Plus Data Center in the Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine at the University of Zurich. The registry was approved by the Supra-Regional Ethics Committee for Clinical Studies, the Swiss Board for Data Security and the Cantonal Ethics Commissions. The AMIS Plus project is officially supported by the Swiss Societies of Cardiology, Internal Medicine and Intensive Care Medicine. The study design and flow of the patients are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Study design.

The present analysis included all patients (N=12,000) enrolled in AMIS Plus between January 2005 and June 2012, with ST-elevation myocardial infarction defined by characteristic symptoms with ECG changes and cardiac marker elevation (creatine kinase MB fraction at least twice the upper limit of normal or troponin I or T above individual hospital cut-off levels for MI). All patients were required to have ST-segment elevation and/or the new development of left bundle branch block on the initial ECG at presentation. A total of 9,370 patients underwent PCI. We then further limited our study population to those patients with STEMI who also had multivessel disease (n=4,941). Three thousand eight hundred and thirty-three patients (77.6%) underwent SPCI and 1,108 (22.4%) underwent MPCI (Figure 1). Multivessel disease was defined as the presence of an angiographic stenosis of ≥50% in at least two of three main coronary arteries and/or involving the LM when a surgical bypass graft was concerned.

STUDY ENDPOINTS, COVARIATE OF INTEREST AND ADDITIONAL VARIABLES

Our study endpoint of interest was in-hospital mortality. We also evaluated a secondary endpoint of in-hospital major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) that included mortality, reinfarction and cerebrovascular events. Our covariate of interest was MPCI use, which we defined as the performance of PCI in at least two or more vessels during STEMI. The MPCI population had only undergone the acute primary PCI procedure and not a staged procedure at the same hospital. Lesions that involved the left main coronary artery (LM) and that were subsequently treated were considered a separate lesion from those involving the left anterior descending and circumflex coronary arteries. The decision regarding SPCI or MPCI attempt was performed at the operating physician’s discretion.

The AMIS Plus has 230 items that address medical history, comorbidities, known cardiovascular risk factors, clinical presentation, out-of-hospital management, early in-hospital management, reperfusion therapy, hospital course, diagnostic tests used or planned, length of stay, discharge medication and discharge destination. Patients are enrolled in the registry on the basis of their final diagnosis. A number of covariates were examined in this study with regard to their association with multivessel PCI and culprit-vessel PCI only. These included: risk factors documented in the patient’s medical history (dyslipidaemia, arterial hypertension and diabetes), obesity (body mass index ≥30 kg/m2), smoking (active or not), and additional non-cardiovascular comorbidities (assessed using the Charlson index). We also included data on immediate drug treatments and discharge medication.

High-risk patients were identified a priori as those with: 1) LM involvement that required treatment with PCI; 2) out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; or 3) Killip class III/IV. We selected these specific categories since they represent clinical scenarios under which patients with STEMI are at high risk for in-hospital mortality and additional revascularisation is believed to be worthwhile.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The results are presented as percentages for categorical variables and analysed using the non-parametric Pearson χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Continuous normally distributed variables are expressed as means±1 standard deviation (SD) and compared using the Student’s unpaired t-test. Continuous non-normally distributed variables are expressed as median and interquartile ranges and analysed using the Mann-Whitney U test. All statistical tests were two-tailed and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A multivariate logistic regression model was examined to determine predictors of MPCI use and included the following variables: age, gender, LM involvement, Killip class >2, Charlson comorbidities weighted index ≥2 and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Moreover, we assessed the association between MPCI and in-hospital mortality. To determine in-hospital mortality predictors, a multivariate logistic regression model included the following variables: age, gender, vessel treated, LM involvement, Killip class >2, Charlson comorbidities weighted index ≥2 and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. We did this in the entire cohort and after stratifying patients based on risk. Adjusted odds ratios in all models are reported from the multivariate models. IBM SPSS software version 19 ( IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

STUDY POPULATION AND MPCI PREDICTORS

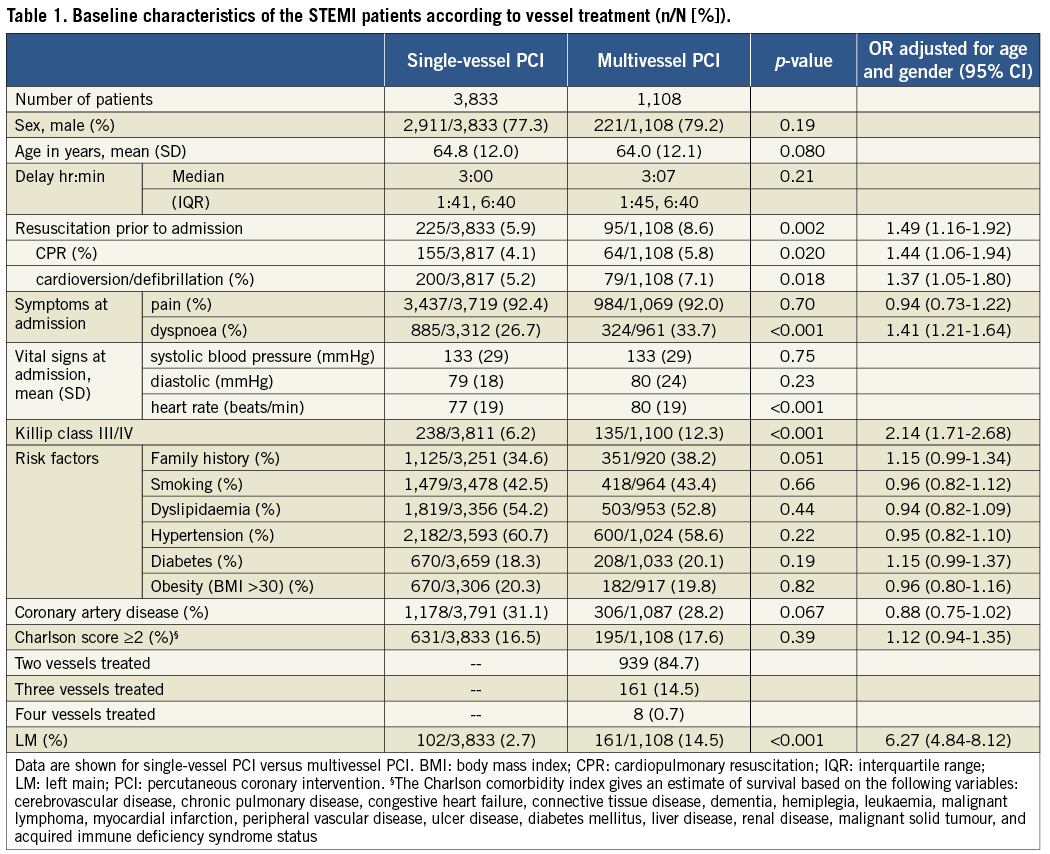

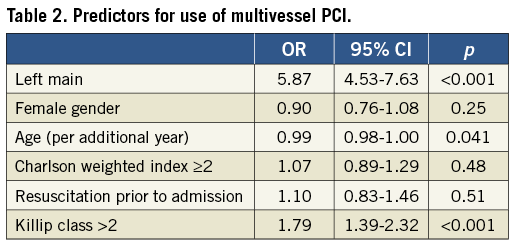

Out of 12,000 patients admitted with a diagnosis of STEMI between 2005 and 2012, we identified 4,941 patients (41.2%) with multivessel disease who underwent PCI. Three thousand eight hundred and thirty-three patients (77.6%) underwent SPCI and 1,108 (22.4%) underwent MPCI (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics stratified by MPCI use are presented in Table 1. In general, rates of MPCI were greater among sicker patients. High-risk patients, identified by the three characteristics, all had higher rates of MPCI use after age and gender adjustment: 8.6% vs. 5.9% for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OR 1.49, 95% CI: 1.16-1.92, p=0.002); 12.3% vs. 6.2% for Killip III/IV (OR 2.14, 95% CI: 1.71-2.68, p<0.001); and 14.5% vs. 2.7% for LM involvement (OR 6.27, 95% CI: 4.84-8.12, p<0.001). In addition, drugs, i.e., glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors/AT antagonists, were used less frequently in patients treated with MPCI (33.2% vs. 39.4%, OR 0.75, 95% CI: 0.65-0.87, p<0.001; 59.3% vs. 62.8%, OR 0.85, 95% CI: 0.74-0.98, p=0.034; 50.0% vs. 61.8%, OR 0.61, 95% CI: 0.54-0.70, p<0.001, respectively). After accounting for additional risk factors, the presence of LM (OR 5.87, 95% CI: 4.53-7.63, p<0.001) and a Killip class III/IV (OR 1.79, 95% CI: 1.39-2.32, p<0.001) were the only factors independently predictive of MPCI use during STEMI (Table 2).

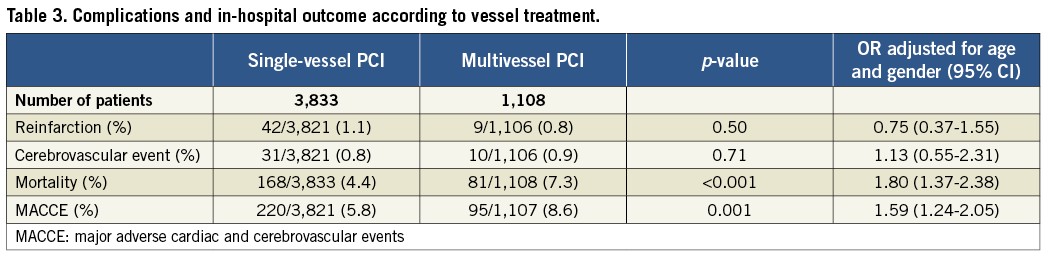

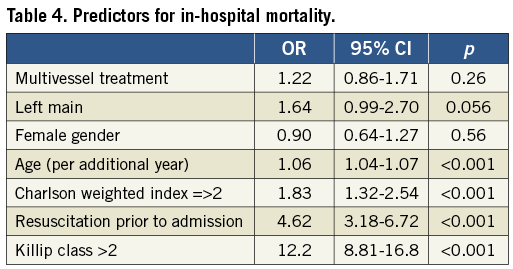

IN-HOSPITAL OUTCOMES AND PREDICTORS OF MORTALITY

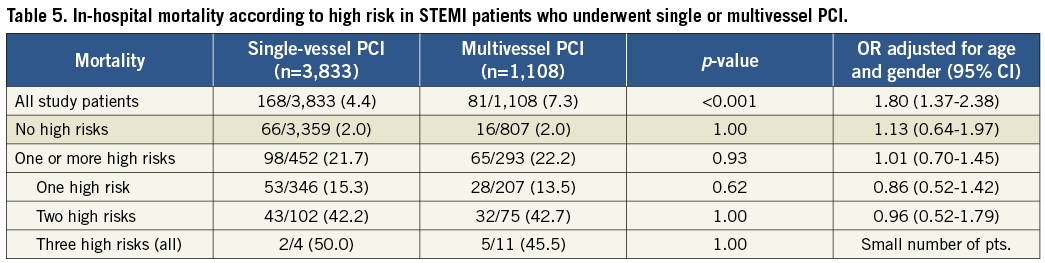

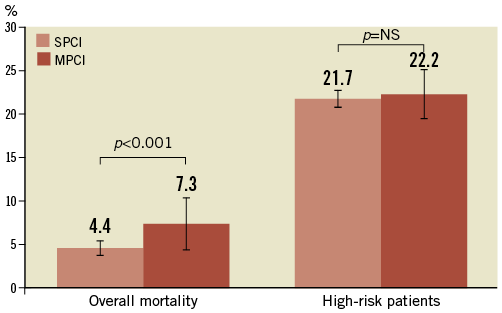

Overall, in-hospital mortality after MPCI was higher when compared with SPCI (7.3% vs. 4.4%, OR 1.80, 95% CI: 1.37-2.38; p<0.001) as well as MACCE (8.6% vs. 5.8%, OR 1.59, 95% CI: 1.24-2.05, p<0.001, Table 3). Age (per additional year), Charlson weighted index ≥2, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and Killip III/IV were identified as predictors of in-hospital mortality (OR 1.06, 95% CI: 1.04-1.07, p<0.001; OR 1.83, 95% CI: 1.32-2.54, p<0.001; OR 4.62, 95% CI: 3.18-6.72, p<0.001; OR 12.2, 95% CI: 8.81-16.8, p<0.001, respectively, Table 4) but not MPCI use (OR 1.22, 95% CI: 0.86-1.71, p=0.26). Differences in in-hospital mortality were completely eliminated when patients were stratified by risk: in-hospital mortality for MPCI vs. SPCI was 2.0% vs. 2.0% (p=1.00) in low-risk patients and 22.2% vs. 21.7% (p=0.93) in high-risk patients (Figure 2 and Table 5).

Figure 2. In-hospital mortality according to high risk in STEMI patients who underwent single or multivessel PCI.

Discussion

Our analysis has several key findings. First, we identified that patients more likely to undergo MPCI are sicker in general and at high risk. Second, MPCI is associated with higher rates of in-hospital mortality and MACCE, but these differences are largely negated after stratifying patients based on risk. The latter finding indicates that MPCI in non-critically ill STEMI patients does not negatively influence in-hospital outcome.

Patients with STEMI and multivessel disease are likely to have a substantial increase in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality due to several factors – and not just the performance of MPCI 2-4. First of all, STEMI patients with multivessel disease are likely to have more extensive coronary disease and lower LV ejection fraction compared to those with single-vessel disease17. It has also been hypothesised that acute myocardial infarction slows flow globally throughout the coronary vessels, due to increased systemic inflammatory response and vasospasm, which may exacerbate outcomes18-20.

There is a large body of literature investigating whether PCI procedures should be extended during the course of STEMI in patients with multivessel disease or whether it should be confined to culprit vessel5,6,14. Existing data are somewhat conflicting and controversial14. Several studies suggested that MPCI during the course of STEMI is associated with increased mortality, MACE and stent thrombosis11,13,21-24. On the contrary, Qarawani et al and Politi et al supported MPCI in the acute phase of STEMI as a feasible and safe attempt resulting in an improved acute clinical course after MPCI and a lower MACE rate at long-term follow-up8,25. Another study revealed incomplete revascularisation as a strong and independent risk factor of death and MACE in patients with STEMI26. The HELP-AMI multicentre, randomised trial found one-time full revascularisation to be a safe procedure7. Investigators concluded, however, that the staged approach to MPCI during the acute phase of MI avoids treating non-relevant lesions unneccesarily7. Also, no economic advantages of one-time MPCI were documented7.

All the studies on MPCI versus SPCI in patients with STEMI and multivessel disease (MVD) were performed on a small population8,25,26. In a meta-analysis of patients with STEMI and MVD, a strategy of staged complete revascularisation appeared to be the best choice in patients with STEMI4,14. In another recently published meta-analysis, one-time MPCI was not beneficial for patients with STEMI, although it did not worsen the mortality rate27.

The rate of MPCI among STEMI patients has reportedly ranged between 0% and 38%10. Full revascularisation, including non-culprit vessels, has been suggested to be most relevant for high-risk patients with cardiogenic shock leading to reduced ischaemia and improved survival28,29. Indeed, currently published guidelines recommend MPCI only in unstable STEMI patients1,5,6. In non-shock STEMI patients, the use of PCI should be focused on the infarct-related or culprit vessel only. However, these recommendations remain based on observational studies where there has been a mixed application of risk-adjustment methods.

Why would MPCI be potentially harmful in STEMI patients? PCI in acute coronary syndromes could cause coronary microembolisation due to the erosion or rupture of a vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque occurring spontaneously30. This leads to periprocedural MIs, contractile dysfunction and reduced coronary reserve30. These potential complications in a non-culprit artery may be poorly tolerated due to simultaneous impairment of the infarct-related and non-related areas22. Second, in the acute phase of STEMI, the significance of the lesion of the non-culprit vessel could be overestimated due to vasoconstriction and endothelial dysfunction31, leading to overtreatment of vessels where the benefit is unlikely to be substantial. In this setting, an initial conservative strategy is likely to be more effective32. Additional reasons for culprit-vessel PCI only include its lower contrast use, which could reduce the risk of acute kidney injury – a powerful predictor of outcomes in STEMI patients. The advantage for staged PCI is that non-culprit lesions can be discussed within a Heart Team to determine the best individual management strategy5,6.

PCI for non-culprit vessels in the acute course of STEMI, excluding the cardiogenic shock setting, is discouraged in recently published ESC guidelines and has been labelled as “inappropriate” in a recent report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force33,34. The accurate treatment strategy in case of STEMI and MVD is still not well established by RCTs33.

In our observational experience, after stratifying patients based on risk, MPCI does not appear to be associated with higher mortality, supporting its potential use for selected patients during the course of STEMI. MPCI may be considered by physicians in terms of convenience for the patients and potential cost reduction compared to post-STEMI staged PCI of non-culprit vessels35.

Study limitations

Our study should be assessed in the context of its limitations, many of which are inherent to registry studies. First, there is the potential for residual confounding factors due to a lack of data on relevant clinical features that could have impacted both on the choice to use MPCI as well as on outcomes. Therefore, to identify the high-risk setting we selected the clinical and angiographic variables, since we were not able to provide more accurate risk stratification based on the GRACE or TIMI score. Second, although the AMIS Plus registry provides data on the number of vessels treated with PCI, the precise anatomical distribution of the lesions and technical features of the procedure itself are unknown. Third, we have no information regarding subsequent treatment of non-culprit vessels (CABG, staged in-hospital revascularisations, and conservative treatment) or follow-up data on the patients following discharge.

Conclusions

STEMI patients with multivessel disease who have undergone MPCI are sicker than those who underwent culprit-vessel PCI only. Furthermore, MPCI does not appear to be associated with higher mortality after stratifying patients based on their risk. Therefore, although MPCI in STEMI patients should continue to be reserved for high-risk groups, physicians should not be reluctant to use this approach when their clinical judgement suggests potential benefit. Large-scale prospective trials should be organised to guide the appropriateness of MPCI during the course of STEMI. The current observation reflects a “real-world” practice which encourages us to perform a randomised clinical trial of MPCI in STEMI in the near future.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.