Abstract

Aims: The mortality rate in patients with STEMI is higher in women than in men. This higher mortality rate is partly accounted for by certain known characteristics inherent in the female population (age, diabetes). Using data from the e-MUST registry on STEMI patients in the Greater Paris area, we assessed the differences between men and women treated with reperfusion strategies.

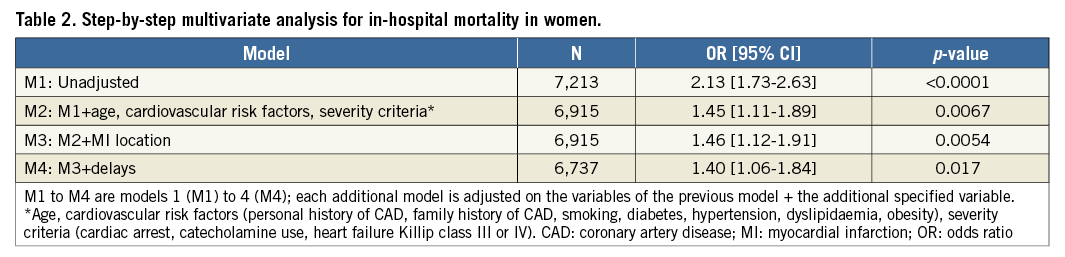

Methods and results: Patients presenting within 24 hours of pain onset between 2006 and 2010 were included in the study. The male and female subpopulations were compared according to their baseline characteristics, their management delays and their early outcomes. Five thousand eight hundred and forty males (78.9%) and 1,557 females (21.1%) were included in the study. In-hospital mortality was significantly higher in women than in men, 143 (9.4%) vs. 254 (4.4%), p<0.0001, with a longer time to treatment initiation, symptoms to call (2.7±3.6 vs. 2.2±3.4 hours, p<0.0001), symptoms to first medical contact (FMC) (3.1±3.7 vs. 2.6±3.4 hours, p<0.0001), and call to FMC (25.6±23.5 vs. 23.6±18.3 min, p=0.02). After adjustment for clinical factors, severity criteria, myocardial infarction (MI) location and delays, mortality remained higher in women than in men with an odds ratio of 1.40 [1.06-1.84], p=0.017.

Conclusions: We demonstrated longer pre-hospital delays and higher in-hospital mortality in women. The increase in the time to treatment alone does not completely explain the persistent increase in mortality. Further studies, public awareness programmes and physician education are necessary to reduce delays and improve the prognosis of STEMI in women.

Introduction

In patients presenting with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), reduced time to treatment initiation and reperfusion (thrombolysis or primary percutaneous coronary intervention [pPCI]) have been shown to improve survival significantly. Rescue and adjunctive PCI are effective therapies after thrombolytic therapy1,2. Studies of sex differences in mortality after myocardial infarction (MI) have consistently indicated that women have higher death rates, especially in short-term follow-up. The differences in baseline and procedural characteristics, such as more advanced age, a higher percentage of diabetics and cardiogenic shock, cannot wholly explain the discrepancy in outcome3. Late presentation and a lower rate in the use of reperfusion therapy may account for increased mortality.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate differences in the therapeutic management of females and males prior to their admission to a cardiology unit for thrombolysis and/or coronary angioplasty, and to assess the average time to treatment implementation and the impact of the delays on the prognosis using data from a prospective pre-hospital management registry of patients with STEMI of less than 24 hours managed by mobile intensive care units (MICU) in the Greater Paris area.

Methods

DATA SOURCE

Our data were collected between 2006 and 2010 from the e-MUST registry, a prospective multicentre registry from the Regional Health Agency of the Greater Paris Area (ARSIF), which includes all patients presenting within 24 hours of an acute STEMI and who were managed by MICUs. All MICU departments of the Greater Paris area took part in this study and enrolled the patients consecutively.

The Greater Paris area is the most populated region of France (11.7 million inhabitants). The emergency physician on site fills in the patient’s medical form on presentation, then adds data on in-hospital outcomes (time of angioplasty when applicable, death and early complications). In-hospital mortality is cross-checked using another hospital database (PMSI). The database is sent to the ARSIF registry department every four months. An external audit was carried out every year in every centre to assess the quality and the completeness of the database. Random selection of patient files was performed over a two-week period with the aim of checking the records of patients admitted for chest pain. The auditors verified that patients presenting with STE-ACS were duly included in the registry. The exhaustiveness of the registry exceeded 90%.

MICUs are special French medical emergency systems. A dispatch centre centralises emergency medical calls via a dedicated telephone number (which is the number 15) and organises an appropriate response with the intention of ensuring the shortest delay between the initial call and the appropriate treatment. In the event of an emergency medical call for chest pain, the medical dispatcher sends a MICU with a physician, a nurse, and a trained driver on board. If a diagnosis of STEMI is confirmed by the physician on-site, the patient is transferred to the cathlab, with or without pre-hospital thrombolysis4.

POPULATION

Patients initially managed by MICUs and presenting with a STEMI with a time delay of less than 24 hours between pain onset and first medical contact (FMC) were included in the analysis. For the purposes of the analysis they were divided according to gender.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data were summarised as means (standard deviation) or median (interquartile interval) where appropriate for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Men and women’s data were compared using the χ² test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. We assessed whether gender was an independent risk of in-hospital mortality by performing a step-by-step multivariate logistic regression successfully adjusted for age, cardiovascular risk factors, severity criteria, myocardial infarction (MI) location and delays. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A p-value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Tests were two-sided.

Results

From 2006 to 2010, 10,362 patients with STEMI within 24 hours after onset of chest pain were identified in our database. We excluded 2,361 patients who were transferred from another hospital for rescue or primary angioplasty and 604 patients without reperfusion strategy (7.5%). The rate of no reperfusion therapy was 10.4% in women and 5.7% in men (p<0.0001). We included in the study 7,397 patients with primary reperfusion therapy, 1,557 (21.1%) women and 5,840 (78.9%) men.

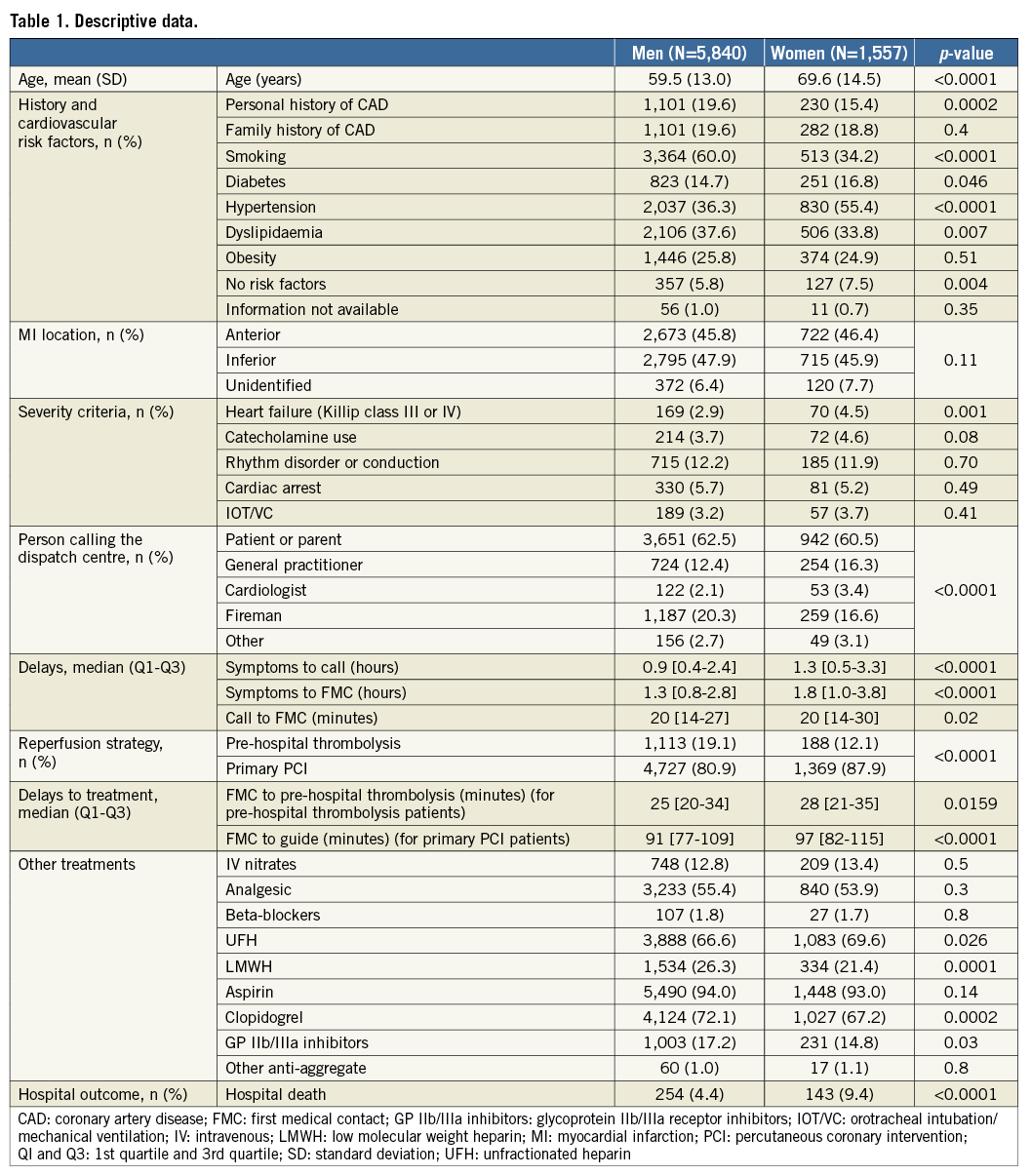

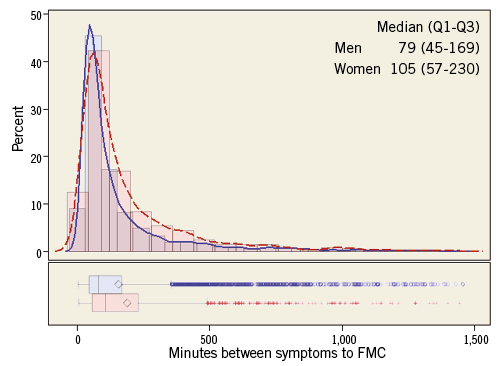

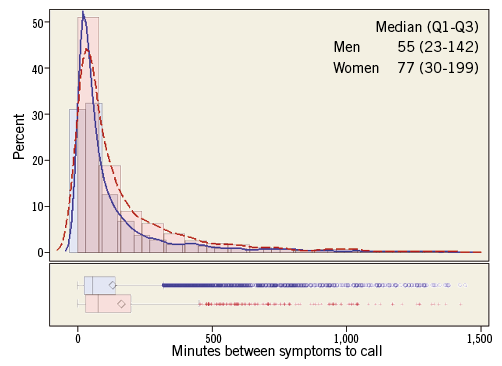

Clinical data and severity criteria are shown in Table 1. Clinical predictors of worse clinical outcome such as old age, diabetes mellitus or cardiogenic shock were significantly higher in women. The description of the call to the dispatch centre and the delays before the call are shown in Table 1. A significantly longer delay before calling with an increased delay of onset of chest pain to FMC was noted in women. The median delay between symptoms to call and symptoms to FMC was also significantly increased in women (Figure 1, Figure 2).

Figure 1. Frequency distribution and box plot of median delays between symptoms to call by gender. Q1 and Q3 (1st quartile and 3rd quartile). Men are represented in blue, and women are represented in red. Curves represent non-parametric kernel density estimate. Box plot indicates the median, upper and lower quartiles (lines), mean (diamond), 1.5 interquartile range (whiskers) and outliers (“+” markers).

Figure 2. Frequency distribution and box plot of median delays between symptoms to first medical contact (FMC) by gender. Men are represented in blue, and women are represented in red. Curves represent non-parametric kernel density estimate. Box plot indicates the median, upper and lower quartiles (lines), mean (diamond), 1.5 interquartile range (whiskers) and outliers (“+” markers).

The reperfusion strategy and the in-hospital mortality are described in Table 1. Reperfusion is performed significantly less in the female population. Thrombolytic therapy was administered significantly less often in women.

A worse in-hospital outcome in women was noted with a higher mortality rate than in men (9.4% versus 4.4%, p<0.0001).

Multivariate analysis, including step-by-step, age, cardiovascular risk factors (personal history of CAD, family history of CAD, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, obesity), severity criteria (cardiac arrest, catecholamine use or heart failure Killip class III or IV), MI location and delays (symptoms to call [five groups: 0’-30’-60’-90’-120’->120’] and call to FMC [four groups 0’-15’-30’-60’->60’]), showed a persistent but less significant increase of mortality in women (Table 2).

Discussion

In-hospital mortality of patients with STEMI treated by a pre-hospital medical system was significantly higher in women than in men: 4.4% vs. 9.4%, p<0.0001. Pre-hospital delays and time to treatment initiation were significantly longer: symptoms to call (2.7±3.6 vs. 2.2±3.4 hours, p<0.0001); symptoms to FMC (3.1±3.7 vs. 2.6±3.4 hours, p<0.0001), call to FMC (25.6±23.5 vs. 23.6±18.3 min, p=0.02). After adjustment for age, cardiovascular risk factors, severity criteria, MI location and delays, mortality remained higher in women than in men with an odds ratio of 1.40 [1.06-1.84], p=0.017.

The higher mortality rate in women with acute STEMI has been widely reported3,5-7. The multivariate analysis carried out in our previously reported study showed that higher hospital mortality persists even after eliminating the numerous confounding factors inherent in this population5 .

Previous studies have suggested that a lower use of pPCI is a major cause of the increased mortality noted in women. Milcent et al studied data extracted from a French national health payment database8. All hospital admissions in France with a discharge diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction were extracted from the database. Women were older (75 vs. 63 years of age; p<0.001) and had a higher rate of hospital mortality (14.8% vs. 6.1%; p<0.0001) than men. Percutaneous coronary interventions were more frequent in men (7.4% vs. 4.8%; 24.4% vs. 14.2% with stent; p<0.001). Mortality adjusted for age and comorbidities was higher in women (p<0.001), with an excess adjusted absolute mortality of 1.95%. Simulation models related 0.46% of this excess to reduced use of procedures. The survival benefit related to percutaneous coronary intervention was lower among women. Similar results were observed in the Swiss Registry in which women were older with a higher rate of comorbidities, a longer time to treatment implementation and less coronary angioplasty (odds ratio 0.65 [0.61-0.69])9. In-hospital mortality was higher (10.7% vs. 6.3%, p<0.001), even in patients undergoing primary angioplasty (4.2% vs. 3.0%, p<0.018). In the New York registry of 11,162 males and 2,561 females under 50 years of age who underwent primary angioplasty for treatment of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) with STEMI, female gender was found to be an independent risk factor of in-hospital mortality10, although the PCI success rate was comparable in both genders. It is to be noted, however, that the use of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors and stents was lower in the female group (58.6% vs. 65.1%, p<0.0001, and 92.5% vs. 94.9%, p<0.0001, respectively).

In contrast, in our study pPCI was used more often as a reperfusion therapy compared to thrombolysis. All patients were triaged by a pre-hospital physician. Coronary angiography followed if necessary by pPCI may have been preferred in women in this setting due to uncertainty in the diagnosis of STEMI or fear of bleeding complications, which are both more frequent in women5. However, despite a higher use of pPCI, in-hospital survival was lower in women.

In our previous study5, we analysed in-hospital data in women with STEMI. A longer delay in the implementation of reperfusion was suggested as a cause for the higher mortality reported in women. The current study integrated data from the pre-hospital phase, including delays before hospital admission. A longer delay between chest pain onset and the first call to an emergency unit was clearly evidenced in women. This delay is probably due to an underestimation of symptoms which are often considered atypical in this population. It seldom occurs to female patients and their families that the symptoms are related to STEMI, which requires urgent care. Consequently, as reported in our study, women tend to contact their GP or a cardiologist rather than use the dedicated phone number for medical emergencies, which would shorten delays to hospital admission and reperfusion. Our study also demonstrated that, once the first contact has been made, the time elapsed before female patients receive medical attention is also longer. In a Spanish study in which patients were matched by age, no difference was found by gender in the time to seeking healthcare11. In contrast, most studies performed to date have reported longer delays in women12,13.

Longer delays in the management of patients with acute STEMI are associated with excess mortality: each additional minute elapsed before treatment initiation increases the mortality rate14-16. The impact of time is even more significant at the onset of symptoms14. Reperfusion strategies are more efficient when they are initiated as early as possible.

One very interesting study published by Pelletier et al showed that, among younger adults (n=1,123 patients [18-55 years]) with ACS, women and men had different access to care. Women were less likely than men to receive care within benchmark times for electrocardiography (≤10 min: 29% vs. 38%, p=0.02) or fibrinolysis (≤30 min: 32% vs. 57%, p=0.01). Women with STEMI were less likely than men to undergo reperfusion therapy (pPCI or fibrinolysis) (83% vs. 91%, p=0.01). Clinical determinants of poorer access to care included anxiety, increased number of risk factors and absence of chest pain. Gender-related determinants included feminine traits of personality and responsibility for housework17. Among the clinical determinants of procedure delays, anxiety was associated with failure to meet the 10-minute benchmark for ECG in women but not in men. Patients with anxiety who present to the emergency department with non-cardiac chest pain tend to be women, and the prevalence of ACS is lower among young women than among young men. These findings suggest that triage personnel might initially dismiss a cardiac event among young women with anxiety, which would result in a longer door-to-ECG interval

In our study, adjustment for delays in treatment reduced the OR for mortality in women versus men but only by 0.4 (model 3 to model 4). Consequently, delays in treatment implementation seem to account only partially for the higher mortality rate observed in women.

Differences in the physiopathology of STEMI between men and women have been suggested to explain this increased mortality. Because oestrogen has protective effects on the cardiovascular system18, women’s myocardium may be more vulnerable to abrupt ischaemia19. A higher occurrence of plaque rupture in men and more frequent plaque erosions with microvascular embolisation in women have been reported20. Moreover, young women share a significantly lower plaque burden and amount of necrotic core than men, but have significantly higher microvascular coronary and cardiac endothelial dysfunction21,22. In women, the rate of spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is higher than in men. Vanzetto et al reported a very interesting study and concluded that, although SCAD is an uncommon disease in the general population, especially in men, it may be responsible for more than 10% of ST-elevation ACS in women below 50 years of age23. Contrary to what is usually thought, this disease does not exclusively affect younger women in the peripartum period, or those carrying inflammatory or collagen disease, but can also be seen in middle-aged females with one or more cardiovascular risk factors. The use of intraluminal imaging devices will probably result in a higher rate of SCAD and intraparietal haematoma being highlighted in this population24. The pathophysiology of SCAD probably involves the formation of an intramural haematoma on the basis of constitutional or acquired arterial wall fragility and mechanical stress, with a risk of longitudinal and axial extension with true lumen compression and possibility of intimal rupture24. The initial treatment of SCAD is not standardised, and the use of antithrombotic and antiplatelet therapy has not been clearly established in this setting23,24. This difference in the physiopathology could partially explain the prognostic difference between women and men.

Our results suggest that public awareness programmes focused on women could improve the outcome of STEMI in this population. Women must be made aware that symptoms such as chest pain and shortness of breath can be indicative of STEMI and require a call to an emergency medical system (EMS) in order to reduce delays to treatment. Puymirat et al demonstrated a striking reduction in STEMI mortality in the French USIC and FAST-MI registries between 1995 and 2010. However, there was an increase in the proportion of women younger than 60 years with STEMI25. In addition, Juliard et al demonstrated for STEMI <6 hours that gender was correlated with hospital mortality in the subgroup of women aged >65 years26. This difference, which was found to be more pronounced in older women, was also demonstrated in the publication by Corrada et al27. Physicians must therefore also be educated to detect symptoms suggesting a STEMI in women. As stated in the paper by Weissler-Snir et al, greater efforts should be devoted to increasing women’s awareness of cardiac symptoms during the pre-hospital course of STEMI28.

Limitations

Partial clinical data were entered in the database. This approach was chosen to facilitate external audits and to obtain a high rate of patients with complete and reliable data.

Although not analysed in the present study, the characteristics of typical vs. atypical chest pain could partly explain the variations in the delays between calls and management of patients with ACS.

Comorbidities such as renal insufficiency and pathologies of the higher functions which are potentially more frequent in elderly patients and may influence the outcome were not recorded in our study.

When this study was carried out, new-generation thienopyridine agents were less widely used than today. This may have influenced the outcomes of the female as well as the male patients.

Medical treatments associated with coronary reperfusion such as aspirin, statins and beta-blockers were not compared in the present study.

Criteria of angiographic complexity and the types of stent implanted were not recorded in this study.

Follow-up was limited to the hospital stay. Analysis of subgroups in registries is limited by the observational nature of the analysis. However, the large number of patients included in our registry limits this potential bias.

Conclusion

In conclusion, using data from a pre-hospital registry on STEMI in the Greater Paris area, we demonstrated longer pre-hospital delays and higher in-hospital mortality in women. The increase in the time to treatment impacted on the prognosis but this factor alone does not explain the persistently higher mortality rate reported in female patients. Further studies, public awareness programmes and physician education are necessary to reduce delays and improve the prognosis of STEMI in women.

| Impact on daily practice Emergency physicians and interventional cardiologists must be aware of the increase in early pre-hospital delays and higher in-hospital mortality in STEMI in women in order to improve management of chest pain in women. Public education programmes targeting women are necessary. STEMI in-hospital mortality can probably be further reduced by lowering vascular complications with an increased use of the radial approach and tailored management of antithrombotic and anticoagulant treatment. |

Funding

Funding of this registry was provided entirely by the Regional Health Agency of the Greater Paris Area (ARSIF), a French Government Agency.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Appendix. Main investigators of the e-MUST Registry (hospitals, emergency physicians and public health physicians)

CH François Quesnay (Mantes la Jolie): Dr Goldman, Dr Hazan, Dr Hoffman, Dr Pasquereau, Dr Viso; Dr Meyer; CH Robert Ballanger (Aulnay sous Bois): Dr Biens, Dr Charestan, Dr Mezard, Dr Raphaël; Dr Benaceur, Dr Guerout; CH Simone Veil (Eaubonne): Dr Belotte, Dr Lefevre, Dr Monfroy, Dr Pouradier, Dr Peyron Fourcade; CH Sud Francilien (Corbeil-Essonnes): Dr Briole, Dr Capitani, Dr Desclefs, Dr Laborne, Dr Pouges, Dr Roignant; Dr Cabo, Dr Lairy; CH Victor Dupouy (Argenteuil): Dr Cuvier; Dr Chevalier; CH d’Etampes (Etampes): Dr Benaicha, Dr Gaffinel, Dr Jeufraux, Dr Nguyen, Dr Pone; Dr Mirolo; CH de Coulommiers (Coulommiers): Dr Compagnon; Dr Echard; CH de Fontainebleau (Fontainebleau): Dr Fossay, Dr Grippon; Dr Bicharzon; CH de Gonesse (Gonesse): Dr Birlouez, Dr Sebbah, Dr Thevenin; Dr Desrues, Dr Hakim; CH de Juvisy sur Orge (Juvisy sur Orge): Dr Aubert, Dr Clavie, Dr Ducommun, Dr Faggianelli, Dr Schvahn; Dr Pillant; CH de Longjumeau (Longjumeau): Dr Coudray, Dr Hautefeuille, Dr Rousseau, Dr Ta; Dr Solvignon; CH de Marne la Vallée (Jossigny): Dr Mathieu, Dr Porcher, Dr Stibbe; Dr Echard; CH de Meaux (Meaux): Dr Bouvet, Dr Goes, Dr Limoges; Dr Echard; CH de Melun (Melun): Dr Letarnec, Dr Rebillard, Dr Tazarourte; Dr Luquet; CH de Montereau (Montereau): Dr Amokrane, Dr Cadot; Dr Derosin; CH de Nemours (Nemours): Dr Coletta, Dr Demiere; Dr Narcisse; CH de Provins (Provins): Dr D’Araujo, Dr Roy, Dr Tarlier; Dr Drevillon; CH de Rambouillet (Rambouillet): Dr Chevrier, Dr Clero, Dr Lederlin; CH de Versailles (Le Chesnay): Dr Boutot, Dr Lambert, Dr Moro, Dr Richard, Dr Sammut; Dr Jourdan, Dr Vinas; CH du Dr Delafontaine (Saint-Denis): Dr Hennequin; Dr Heurte; CH d’Arpajon (Arpajon): Dr Bensalem, Dr Rivoal, Dr Touitou, Mme Rodriguez; Dr Durand; CH d’Orsay (Orsay): Dr Alayrac, Dr Hellio, Dr Nunes; Dr Manet; CHI Le Raincy-Montfermeil (Montfermeil): Dr Beruben, Dr Cavagna, Dr Kergueno; Dr Hennion, Dr Lesgourgues; CHI Poissy-Saint Germain en Laye (Poissy): Dr Getti, Dr Lefevre, Dr Ramaut, Dr Ruiz; Dr Lellouch, Dr Razafimamonjy; CHI de Villeneuve Saint Georges (Villeneuve Saint Georges): Dr Auger, Dr Bergeron, Dr Meinadier, Dr Tshisumbule; Dr Casciani; CHI des Portes de l’Oise (Beaumont): Dr Binda, Dr Le Foll-Llanas, Dr Rakotonirina; Dr Bertiaux; Hôpital Avicenne-APHP (Bobigny): Dr Lenoir, Pr Adnet, Pr Lapostolle; Dr Duclos; Hôpital Beaujon-APHP (Clichy): Dr Devaud, Dr Duchateau, Pr Mantz; Dr Bendersky; Hôpital Henri Mondor-APHP (Créteil): Dr Aurore, Dr Bertrand, Dr Boche, Dr Goldstein, Dr Jacob, Dr Ladka, Dr Penet, Pr Marty; Dr Hemery; Hôpital Hôtel Dieu-APHP (Paris): Dr Boizat, Dr Bourgeois, Dr Eche, Dr Kierzek, Dr Sahakian, Pr Pourriat; Dr Bouam; Hôpital Lariboisière-APHP (Paris): Dr Chaplain, Dr Gueye, Dr Payen; Dr Brechat, Dr Lebrun, Dr Segouin; Hôpital Necker-APHP (Paris): Dr Greffet, Dr Jaffry, Dr Lamhaut, Pr Carli; Dr Le Bihan-Benjamin; Hôpital Pitié-Salpétrière-APHP (Paris): Dr Boon, Dr Delay, Dr Ecollan, Dr Kergueno; Dr Rufat, Pr Baudelou; Hôpital Raymond Poincaré-APHP (Garches): Dr Baer, Dr Cahun-Giraud, Dr Goddet, Dr Lebail; Dr Maillard; Hôpital Saint-Antoine-APHP (Paris): Dr Bourquard, Dr Brard; Dr Boule, Dr Marty; Hôpital de Pontoise (Pontoise): Dr Boukacem, Dr Dupas, Dr Giroud, Dr Ricard-Hibon; Dr Decup; BSPP G1 Montreuil (Montreuil): Dr Bartou, Dr Caballe, Dr Courtiol, Dr Ramdani, Dr Violin; BSPP G2 Vitry (Vitry): Dr Ernouf, Dr Lefort, Dr Mlynski; BSPP G3 Plessis-Clamart (Clamart): Dr Bon, Dr Culoma, Dr Maurin, Dr Rivet; BSPP Service Médical d’Urgence (Paris): Dr Domanski, Dr Jost, Pr Tourtier; CH André Grégoire (Montreuil): Dr Menguy; CMC Foch (Suresnes): Dr Leclerc; CMC Marie Lannelongue (Le Plessis Robinson): Dr Vallet; CMC Parly 2 (Le Chesnay): Dr Baget, Dr Debris, Dr de Livron; Centre Cardiologique d’Evecquemont (Evecquemont): Dr Herman; Clinique Alleray Labrouste (Paris): Dr Herman, Dr Pioger; Clinique Ambroise Paré (Neuilly sur Seine): Dr Bucquoit; Clinique Bizet (Paris): Dr Housni, Dr Rousseau; Clinique Cardiologique du Nord (Saint-Denis): Dr Carradot; Clinique Turin (Paris): Dr Gueyouche, Dr Leminou, Dr Morange; Clinique les Fontaines (Melun): Dr Grandcoin; Hôpital Ambroise Paré (Boulogne Billancourt): Dr Lot; Hôpital Américain de Paris (Neuilly sur Seine): Dr Richard; Hôpital Bichat-APHP (Paris): Dr Buzzi, Dr Deoliveira, Dr Gardesse, Dr Lê-leplat; Hôpital Cochin-APHP (Paris): Dr Dreau, Dr Frenkiel; Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou-APHP (Paris): Dr Heudes, Dr Karafilovic, Pr Chatellier; Hôpital Européen de Paris - La Roseraie (Aubervilliers): Dr Allouch, Dr Lebovisci; Hôpital Privé d’Antony (Antony): Dr Gedin; Hôpital Saint-Joseph (Paris): Dr Gaillard, Dr Rejasse; Hôpital Tenon-APHP (Paris): Dr Lukacs; Hôpital d’Instruction des Armées du Val de Grace (Paris): Dr Romary; Institut Cardiovasculaire Paris Sud - Claude Galien (Quincy sous Sénart): Dr Servigne, Dr Vollaire; Institut Cardiovasculaire Paris Sud - Jacques Cartier (Massy): Dr Cohen-Attia, Dr Gedin, Dr Lequeu, Dr Vollaire; Institut Mutualiste Montsouris (Paris): Dr Gayer, Dr Germain.