CASE SUMMARY

BACKGROUND: A 68-year-old male smoker presented with progressive symptoms of vertebrobasilar insufficiency and angina. His past medical history included arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia as well as diffuse coronary artery disease including left main disease. Of note, he had undergone coronary bypass surgery 12 years earlier utilising the left internal mammary artery.

INVESTIGATION: Physical examination, laboratory tests, duplex ultrasound imaging, contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging and coronary angiography.

DIAGNOSIS: Severe bifurcation stenosis of the left subclavian and vertebral artery with consecutive subclavian steal syndrome and myocardial ischaemia.

MANAGEMENT: Bifurcation T-stenting using a self-expandable bare metal and a coronary drug-eluting stent.

KEYWORDS: bare metal stent, drug-eluting stent, peripheral intervention, subclavian artery, subclavian steal syndrome, T-stenting technique, vertebral artery

PRESENTATION OF THE CASE

A 68-year-old male smoker presented with progressive dizziness, vertigo and temporary diplopia existing for two months. Six weeks previously, he had suffered from a sudden drop attack. Moreover, he complained about exertional angina during the last quarter of the year. Apart from that, he had no other symptoms. His past medical history included arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia as well as diffuse coronary artery disease including left main disease. Of note, he had undergone coronary bypass surgery 12 years earlier utilising the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) on the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery and two venous grafts on the left circumflex artery (LCX) and right coronary artery (RCA). He was on a long-term medication consisting of acetylsalicylic acid, simvastatin, bisoprolol, ramipril, and metformin. On clinical examination left carotid and subclavian bruits were noted. He was found to have a 55 mmHg difference in upper extremity systolic blood pressure with 125 mmHg on the right and 70 mmHg on the left arm. Pulses in the lower extremities were intact with a systolic blood pressure of 160 mmHg on both legs. ECG and the laboratory tests showed no abnormalities.

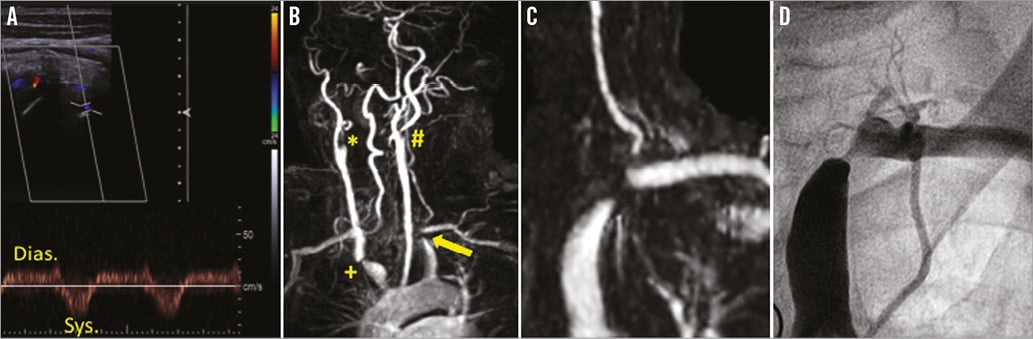

Non-invasive imaging using duplex ultrasound suggested diffuse atherosclerotic disease of the extracranial arteries, including severe stenosis of the proximal left subclavian artery (SA) (>250 cm/s) with alternating flow within the left vertebral artery (VA) under resting conditions (Figure 1A), of the innominate artery (≈200 cm/s) as well as of the left internal carotid artery (≈200 cm/s), and occlusion of the right carotid artery with left to right crossflow via the anterior cerebral artery on transcranial Doppler examination. Clinical assessment by a neurologist confirmed symptomatic SA stenosis with consecutive subclavian steal syndrome in this patient with diffuse supra-aortic vessel disease. For further evaluation contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging was performed revealing the complex stenosis of the left SA at the mid segment involving the left vertebral artery origin (Figure 1B, Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Subclavian steal syndrome caused by advanced supra-aortic disease. A) Colour-coded Doppler ultrasound imaging of subclavian steal syndrome demonstrating an alternating flow within the extracranial left verterbral artery (VA) under resting conditions with antegrade flow in the diastolic (Dias.) and retrograde flow in the systolic (Sys.) phase due to severe stenosis of the proximal left subclavian artery (SA). B) MR angiography of the supra-aortic arteries revealing filiform stenosis of the left SA (arrow) as well as the concomitant lesions including occlusion of the right (*) and stenosis of the left internal carotid artery (#) and of the innominate artery (+). C) Magnification of the MRA demonstrates the close relation of the high grade stenosis of the left SA and the nearby stenosis of the VA. D) Conventional angiography clearly demonstrates the SA stenosis and the retrograde perfused nearby VA as well as the antegrade perfused LIMA origin.

Subsequent coronary angiography demonstrated a patent venous graft on the dominant and proximal occluded RCA, a filiform stenosis of the left main artery with occlusion of the proximal LAD and a rather small LCX with occlusion of a marginal branch. The venous graft supplying the marginal branch was also occluded. Angiography of the left SA depicted the severe stenosis at the curvature of the SA with an alternating flow in the nearby VA as well as an antegrade flow in the LIMA graft supplying the LAD (Figure 1D).

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERT’S OPINION

In this patient, over the years, multiple cardiovascular risk factors led to an extensive atherosclerosis and caused an intermittent subclavian steal syndrome.

The patient’s symptoms are probably due to vertebrobasilar and myocardial ischaemia as a consequence of an alternating flow in the vertebral artery and in the LIMA graft as a result of a pressure gradient caused by a severe stenosis of the proximal left subclavian artery. However, embolisation of atherosclerotic material as a cause of neurological events cannot be entirely excluded1.

In general, a subclavian artery stenosis increases cardiovascular mortality. In particular, the involvement of the LIMA graft, supplying the LAD, puts the life of our patient at risk. Therefore, the first and most important treatment objective is the revascularisation of the subclavian artery. According to the ESC guidelines and following a previously reported favourable five-year primary patency rate of 89% and a 95% secondary patency rate in those patients with symptomatic restenosis2, we would choose the endovascular-first approach.

Access to the subclavian artery would be achieved through the common femoral artery, using a 6 Fr sheath and a 0.035” guidewire. A proper placement of the stent to cover the stenosis fully but not to compromise the vertebral artery or the LIMA bypass is mandatory. For that reason, we would choose a balloon-expandable stent, which is not likely to move during expansion as can happen with self-expanding nitinol stents.

From our point of view, Figure 1D shows a sufficient filling of the vertebral artery origin, no stenosis but only an unsteadiness concerning the vessel wall. An ostial stenosis of the vertebral artery may have been simply pretended at the MRT (Figure 1C) because of its angulated take-off. Nonetheless, stenting of the subclavian artery may compromise the adjacent vertebral artery, as well as the LIMA graft. In order to deal with that, we would secure both vessels by introducing 0.018” guidewires transbrachially. This would allow for kissing balloon angioplasty or provisional stenting in case of flow-limiting lumen constriction. Furthermore, the transbrachial sheath would enable additional angiography in order to visualise the take-offs of the vessels precisely.

In a second step, a few weeks after the initial procedure and dependent on symptoms and the general condition of the patient, the moderate left internal carotid artery stenosis might be considered for revascularisation in order to prevent stroke. The right internal carotid artery occlusion may have worsened symptoms of the subclavian steal but does not itself require intervention because there is a sufficient left to right cross flow.

The patient’s cardiovascular risk factors have to be controlled, and a dual antiplatelet therapy for 30 days would be advisable.

Conflict of interest statement

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

How would I treat?

THE INVITED EXPERTS’ OPINION

This 68-year-old patient presented with multisite artery disease characterised by an advanced involvement of the supra-aortic trunks as well as of the coronary arteries. The 2011 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral artery diseases recommend, as a general rule, to treat the symptomatic territory first in patients requiring multisite revascularisation3. The patient described has coronary-subclavian steal syndrome, and the treatment of the left subclavian artery (SA) stenosis should lead to an improvement of both vertebrobasilar symptoms– by re-establishing an antegrade perfusion in the left vertebral artery (VA) –and exertional angina– by improving the flow to the LIMA graft4. While a surgical approach to subclavian steal syndrome –using axillo-axillary or carotid subclavian bypasses– has been described with good long-term patency outcomes5, in most centres these lesions are approached percutaneously. In the present case, the advanced supra-aortic disease (i.e., additional significant stenosis of the innominate artery, occlusion of the right internal and stenosis of the left internal carotid arteries) precludes surgical options anyway. Based on the limited images at our disposal, we do not believe that the origin of the left VA is significantly stenosed, though arising very close to the SA lesion. Of note, MRA –which is a flow study and not an anatomic study– may overestimate lesions in vascular territories at low flow (such as at the origin of the left VA in the presence of alternating flow).

With respect to the technical aspects, we would approach this intervention by a retrograde femoral access. The patient would receive aspirin and 5,000 IU of unfractionated heparin. Using a 5 Fr Judkins right diagnostic catheter to engage the left SA, a 0.035” floppy hydrophilic wire (e.g., Glidewire®; Terumo Corp., Tokyo, Japan) should be able to pass the lesion and be followed by the diagnostic catheter across the lesion. The floppy wire should then be exchanged for a 0.035” long stiff wire (e.g., Supra Core®; Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The short femoral sheath is then exchanged for a 90 cm long 6 Fr sheath (e.g., Flexor Shuttle Select® Guiding Sheath; Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA), which is engaged over the wire at the origin of the SA. An angiogram with digital subtraction function and store-image function is performed. Balloon predilatation is performed with an undersized 0.035” over-the-wire (OTW) balloon (e.g., 5.0×40 mm Admiral Xtreme™; Invatec-Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Using the stored ground image as reference, a self-expanding nitinol stent is deployed across the origin of the VA (e.g., 8.0×60 mm, S.M.A.R.T® Vascular Stent; Cordis, Johnson & Johnson, Warren, NJ, USA) and post-dilated (e.g., 7.0×40 mm Admiral). In our experience, there is no need to place a filter emboli protection device in the VA as cerebral embolic events in this setting (i.e., flow reversal in the VA) are exceedingly rare. In case of a stenosis of the origin of the VA artery we would consider performing the procedure using instead a long 7 Fr sheath and either securing the VA with a 0.014” wire –in case of moderate lesion of the VA ostium– or stenting the origin of the VA (e.g., with a coronary stent) before stenting the SA (T stent) if the VA stenosis is severe.

Last but not least, this patient has advanced internal carotid disease –probably asymptomatic– which requires attention. In the presence of a contralateral carotid occlusion an asymptomatic revascularisation of carotid stenosis of ≥70% should be considered. In this setting, carotid artery stenting should be favoured over endarterectomy, as the presence of contralateral carotid occlusion increases the risk of stroke with surgery but not with stenting6.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.