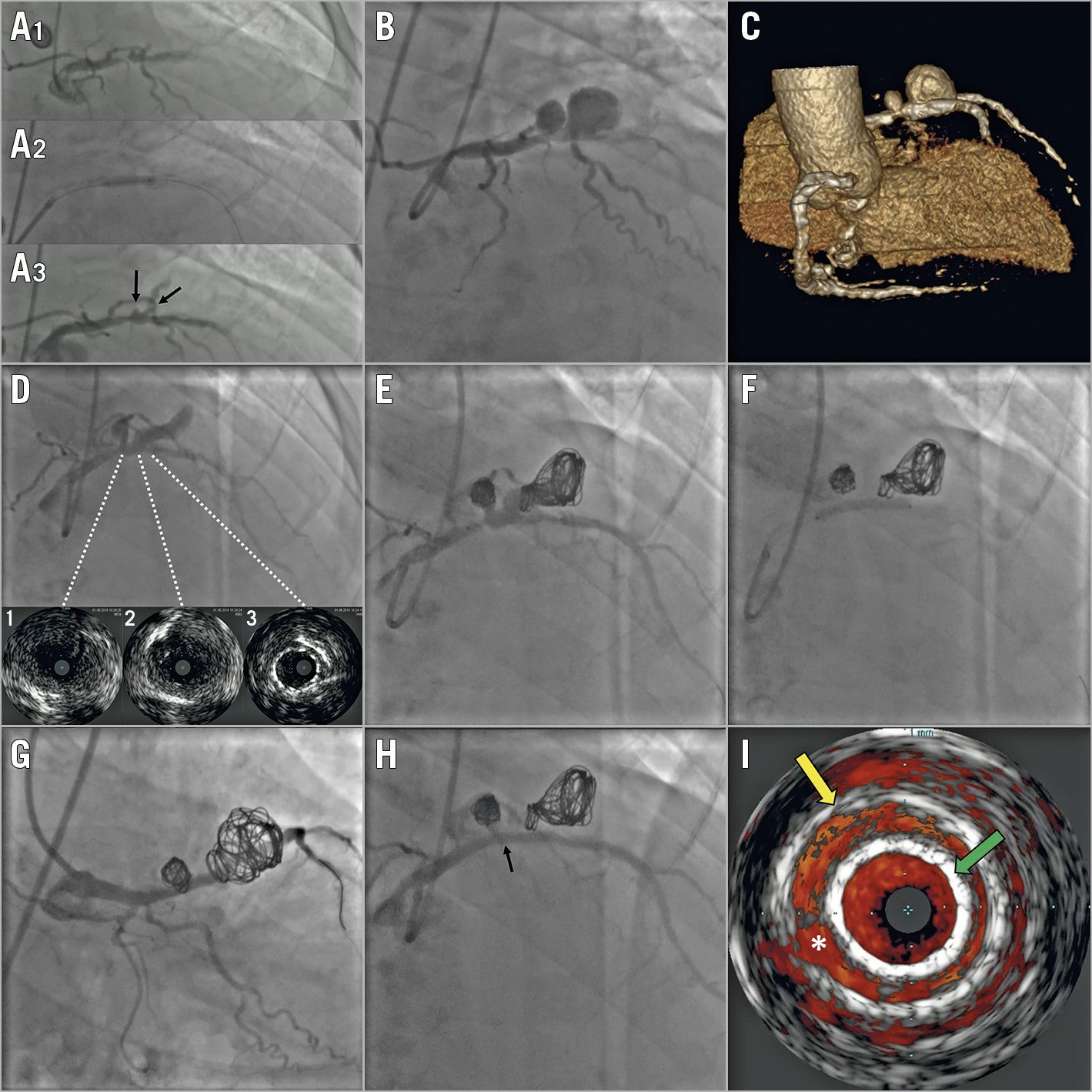

Figure 1. Evolution and management of the giant dual-chamber pseudoaneurysm. A1) - A3) Urgent revascularisation of the proximal LAD with a non-compliant balloon. The arrows indicate the origin of two close diagonal branches. B) Seven-day control angiography showing the giant dual-chamber pseudoaneurysm, corresponding to the origin of the two diagonal branches. C) 3D volume-rendering view from coronary computed tomography angiography. D) Ten-day control angiography and IVUS imaging with different cross-sections showing the damage to the vessel (1-2) and the proximal edge of the distally migrated stent (3). E) Residual flow after coil embolisation. F) Stent deployment. G) Final result: a caudal view. No residual flow is detected on angiography. H) Cranial view. The arrow indicates the leak area on IVUS. I) Colour-flow IVUS imaging showing a small leak (*) between the stent (green arrow) and the pseudoaneurysm wall (yellow arrow).

A 73-year-old male patient, previously treated with percutaneous coronary intervention for a heavily calcified severe stenosis of the proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD), was admitted to our institution for non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction complicated by third-degree atrioventricular block and acute pulmonary oedema. Urgent coronary angiography revealed a severe restenosis of the proximal LAD treated with a non-compliant balloon (Figure 1A1-Figure 1A3). Seven-day control angiography showed a giant dual-chamber pseudoaneurysm of the proximal LAD (Figure 1B, Moving image 1, Moving image 2), confirmed at coronary computed tomography angiography (Figure 1C). Intravascular ultrasound imaging (IVUS) suggested extended damage of the proximal LAD (Figure 1D).

Several percutaneous options had been discussed. The sole implantation of a covered stent would have required a clear delineation of the damaged area to avoid the risk of incomplete sealing. Coil embolisation would have resulted in a residual flow in the presence of a wide neck. Finally, a stent-assisted coil embolisation technique had been considered unsuitable due to the presence of multiple chambers.

The scheduled procedure was performed with a 7 Fr transfemoral approach. A dedicated microcatheter (Echelon™; Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was placed through the neck of the pseudoaneurysm inside the distal chamber, then the 3×24 mm extended-polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) stent (BeGraft; Bentley Innomed GmbH, Hechingen, Germany) was advanced within the LAD, ready to be used. Three coils (20×50 mm, 18×40 mm, and 18×40 mm) were detached in the distal chamber (Axium™; Medtronic) and one (10×30 mm) in the proximal, with mild residual filling (Figure 1E, Moving image 3). The stent was then deployed (Figure 1F), observing pseudoaneurysm exclusion on angiography (Figure 1G, Figure 1H, Moving image 4-Moving image 6). Colour-flow IVUS imaging showed a small leak due to pseudoaneurysmal dilatation (Figure 1I, Moving image 7). The three-month follow-up showed no significant angiographic/IVUS changes.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.

Moving image 1. Caudal view showing the filling of both chambers.

Moving image 2. Right anterior oblique cranial view of the pseudoaneurysm.

Moving image 3. Residual flow after coil embolisation.

Moving image 4. Final result: caudal view showing the exclusion of the pseudoaneurysm.

Moving image 5. Final result: left anterior oblique cranial view.

Moving image 6. Final result: right anterior oblique cranial view.

Moving image 7. Final colour-flow IVUS imaging showing a short area with slight stent malapposition.