Abstract

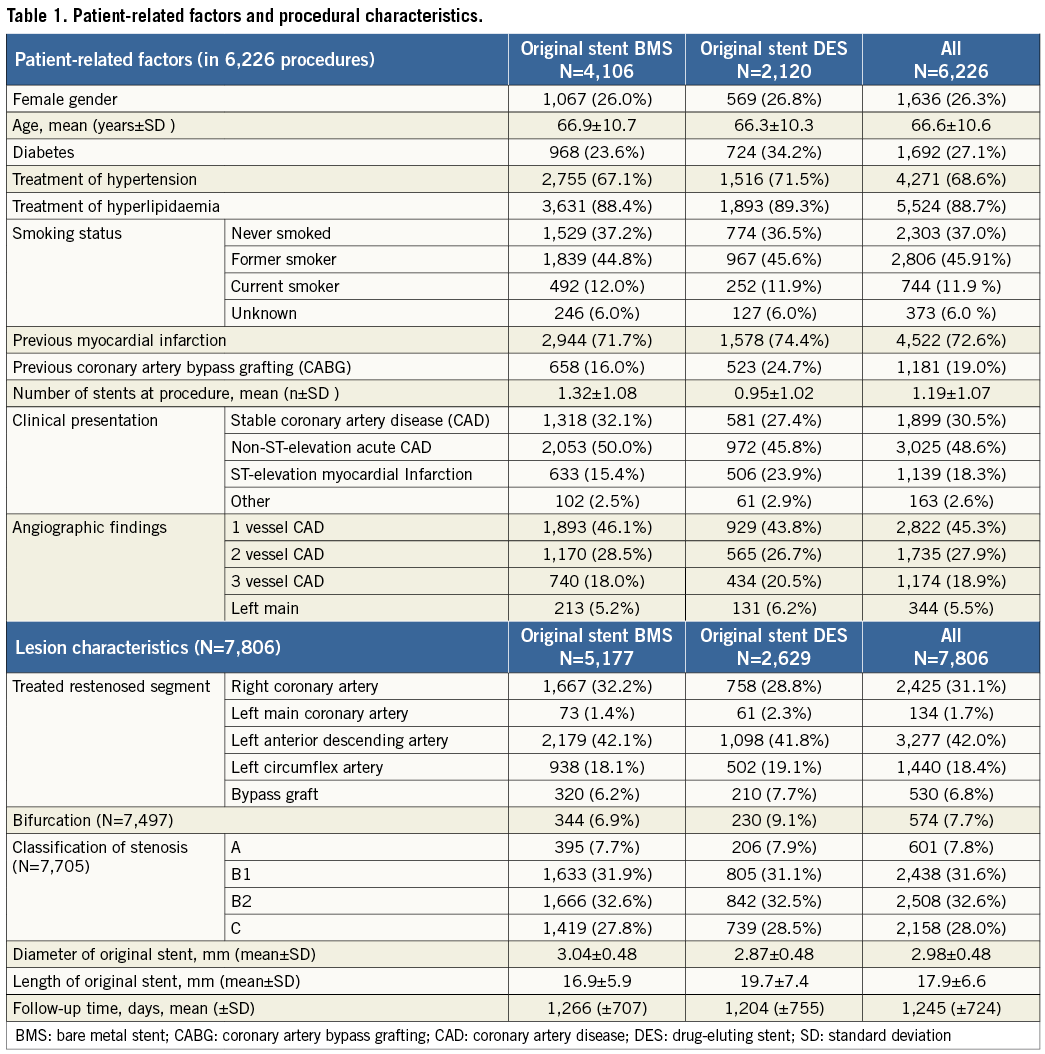

Aims: The aim of this study was to evaluate treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis (ISR).

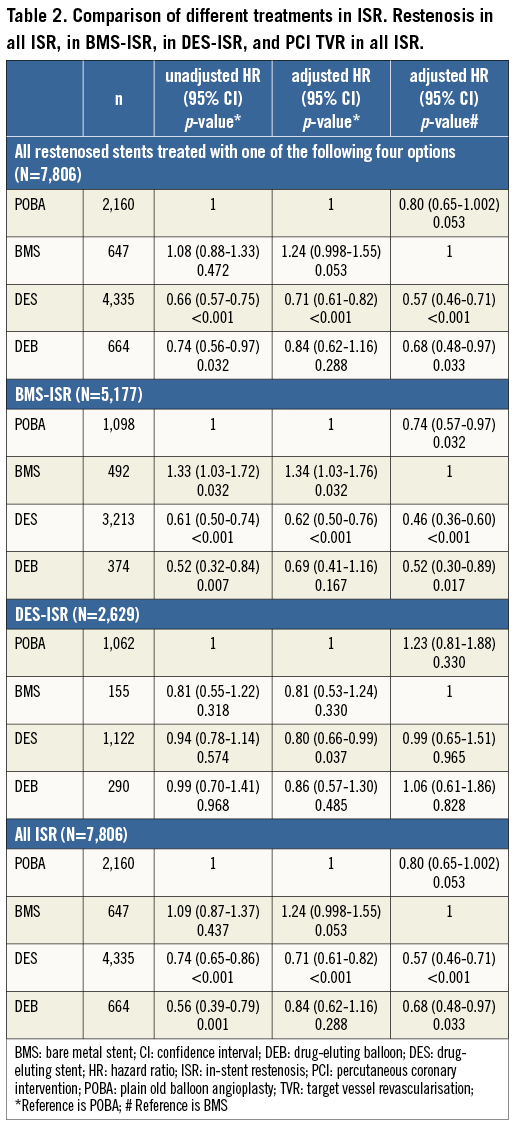

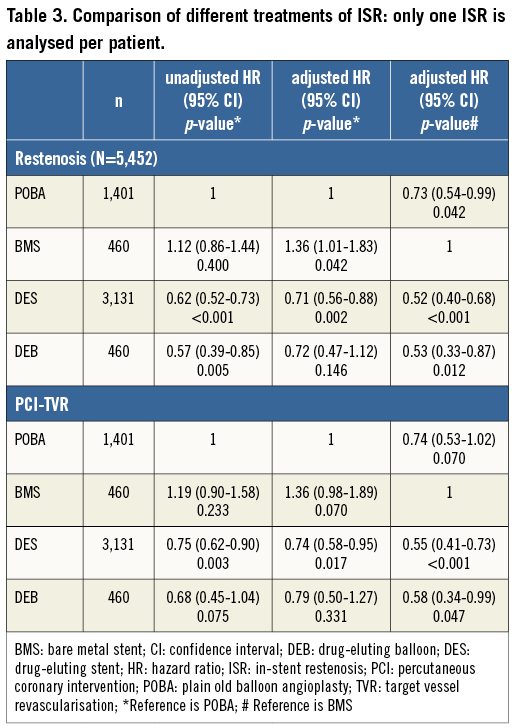

Methods and results: We investigated interventions for ISR and the occurrence of re-restenosis in the Swedish Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR). From January 1st 2005 to March 3rd 2012, 212,166 coronary segments were treated and 7,806 restenoses analysed. During seven years of follow-up 1,079 re-restenoses were registered on clinically driven angiography. For BMS-ISR the adjusted risk of re-restenosis was significantly lower with DES (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 0.71, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.61-0.82), tended to be lower with DEB (HR 0.84, 95% CI: 0.62-1.16), but higher with BMS (HR 1.24, 95% CI: 1.0-1.55) as compared to balloon angioplasty. For DES-ISR a new DES was associated with a significantly lower adjusted risk of re-restenosis (HR 0.80, 95% CI: 0.66-0.99), and a similar but non-significant reduction with DEB (HR 0.86, 95% CI: 0.57-1.30) and BMS (HR 0.81, 95% CI: 0.53-1.24) compared to balloon angioplasty. For DES-ISR a DES with a different drug was not more effective than a DES with the same drug.

Conclusions: ISR in BMS should be treated with DES or DEB while the optimal treatment of ISR in DES remains to be proven.

Introduction

Coronary in-stent restenosis (ISR) is a common clinical problem that continues to be one of the most important limitations of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). ISR is associated with significant morbidity and costs, and is not a benign entity, with a wide spectrum of clinical presentation1,2. The reported in-stent restenosis frequency varies among different types of stents, characteristics of treated lesions and patient characteristics. ISR occurs in about 15%-35% of lesions treated with a bare metal stent (BMS)3, the rate of ISR is usually lower after the implantation of a drug-eluting stent (DES), often less than 10%4,5, but considerably higher when treating more complex lesions6,7.

There are no clearly established standards of treatment for ISR, but there are numerous options: DES has shown a considerable and durable advantage over balloon angioplasty8 and BMS4,5 in the treatment of BMS-ISR. The assessment of drug-eluting balloon (DEB) therapy in patients with BMS-ISR has shown consistent results in favour of this device compared with non-coated balloon angioplasty9.

At present, it remains unclear which strategy is best in the treatment of DES-ISR. Whereas observational studies showed advantages of novel DES implantation over (cutting) balloon angioplasty and vascular brachytherapy (VBT), a recent observational study reported no differences in target lesion revascularisation (TLR) rates between DES and balloon angioplasty on a two-year follow-up10. DEB therapy showed favourable results in smaller trials compared to balloon angioplasty in the treatment of DES-ISR11,12. Since the use of DES is now widespread even in complex lesions and off-label indications, the problem of ISR in drug-eluting stents is not negligible. Treatment results are considerably worse compared to BMS-ISR, and rates of re-restenosis are consistently higher13.

The Swedish Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR) registry, with complete nationwide enrolment and registration of restenosis of any previously implanted stent anywhere in the country, offered a unique opportunity to evaluate treatment for ISR.

Methods

STUDY POPULATION

Our study included all PCI-treated coronary in-stent restenosis (ISR) in Sweden from January 1st 2005 to March 3rd 2012. The data were analysed with regard to different types of treatment, patient and stenosis characteristics. The primary objective was to evaluate the results of different types of treatment for ISR as detected in clinically driven angiography. The study endpoint was occurrence of re-restenosis until the end of the follow-up period. Re-restenosis was defined as a luminal renarrowing of at least 50% at follow-up angiography in a previously treated coronary segment.

SCAAR DATA

The SCAAR data have been described elsewhere14.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We summarised baseline characteristics of the patients with mean and standard deviations for continuous variables and percentages for discrete variables. Cumulative event rates were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. The primary objective was to evaluate incidence and outcome after treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis. The primary outcome variable was clinically driven restenosis with angiographic confirmation. As a secondary event, we also analysed repeat target lesion revascularisation performed with PCI, PCI-TLR. The cumulative adjusted relative risk of the primary outcome variable was calculated using the Cox proportional hazard method with the variables shown in Table 1 (except follow-up time), together with the type of ISR treatment (DES/BMS/DEB/balloon angioplasty), type of original stent (DES/BMS), treating centre and year of procedure. Because of the fact that different devices used in one individual patient/procedure were not statistically independent of each other, we also performed separate sensitivity analyses in which only one randomly selected segment (device) per patient was analysed (Table 3). To test statistical interaction between treatment and type of the original stent (DES/BMS) an interaction variable, “treatment*original stent type”, was introduced in a separate model. In another separate analysis, the main statistical model was used, but DES was divided into two groups: old DES were classified as CYPHER® and CYPHER SELECT® (Cordis Corporation, Miami, FL, USA), TAXUSTM Express2TM and TAXUS® Liberté® (Boston Scientific Corporation, Natick, MA, USA), Endeavor® (Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA); and new DES as Endeavor® Resolute (Medtronic Inc.), XIENCE V®, XIENCE PRIMETM (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA) and PromusTM and PROMUSTM Element (Boston Scientific Corporation)15.

Due to the limited number of events in the analysis of change of stent drug in DES-ISR, only these variables were forced into the statistical model when change of stent drug was analysed: change of drug, diameter of the stent, length of the stent, diabetes, treated vessel, year of treatment, treating hospital and indication of the procedure. In an additional analysis we tested the statistical interaction between change of drug (change/no change) and type of drug (sirolimus/paclitaxel/everolimus/zotarolimus/biolimus) by introducing an interaction term, “change of drug*type of drug” into the statistical model. If diameter or length was unknown the information was taken from the original stent. All reported p-values are two-sided. The analyses were performed with the use of SPSS statistical software version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) or Stata/MP version 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

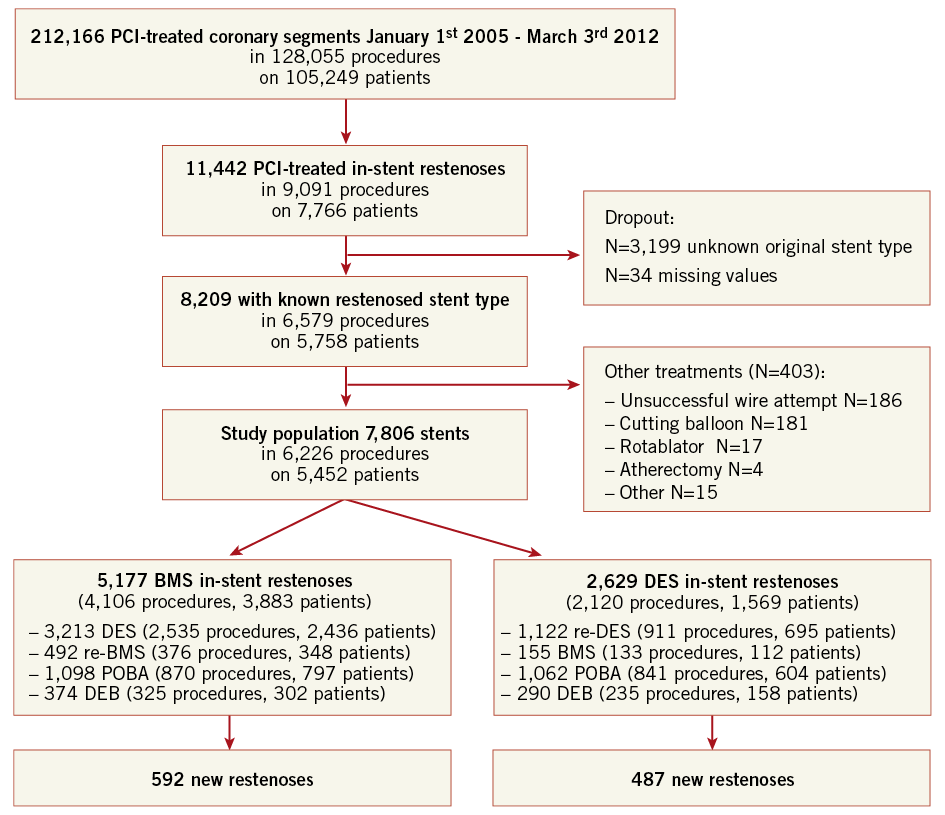

During the study period 212,166 coronary lesions were treated in Sweden (Figure 1), of which 11,442 were recorded in the registry as in-stent restenosis and of these the type and the characteristics of the original stent were known in 8,209 cases. The study population consisted of 7,806 ISR after removal of 403 ISR with a more unusual new treatment or just wire attempt. DES was the most common new treatment in ISR, with 4,335 stents, while BMS was used in 647, DEB in 664 (in 27 cases with additional BMS) and balloon angioplasty in 2,160 ISR. The DEBs used were SeQuent® Please (B. Braun AG, Melsungen, Germany) in 82% of the cases, Elutax (Aachen Resonance GmbH, Aachen, Germany) in 14%, and two other types of DEBs in less than 5%. The original stent was a BMS in 5,177 cases and a DES in 2,629 cases. The background and procedural factors in these two groups are summarised in Table 1. Treatment of ISR with DES, BMS and balloon angioplasty had similar follow-up durations (1,266±707 days, 1,204±755 days and 1,245±724 days, respectively). DEB treatment of ISR had a considerably shorter follow-up time (430±271 days).

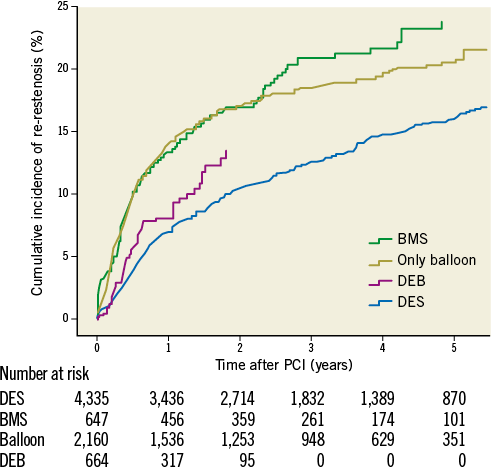

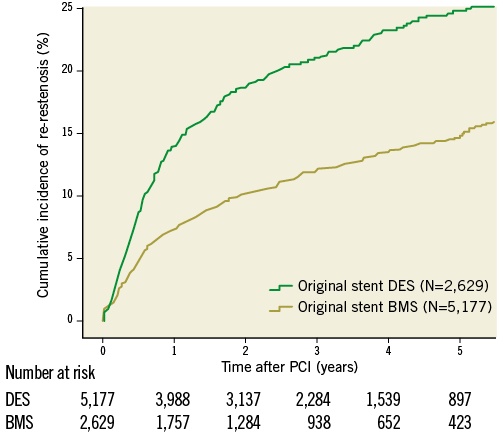

In total, 1,079 re-restenoses occurred, 592 in BMS-ISR and 487 in DES-ISR. As depicted in Figure 1, ISR in BMS were mainly treated with a DES (62%), by balloon angioplasty (21%), new BMS (9.5%), and DEB (7.2%). ISR in DES were treated with a new DES, balloon dilatation, DEB and BMS in 43%, 40%, 11% and 6%, respectively. The long-term incidence of new restenosis (re-restenosis) of these ISR is illustrated in Figure 2. The rates of new restenosis were generally low. For the new treatment with DES, DEB, BMS and balloon angioplasty the recorded rates of re-restenosis within a year were 7%, 8%, 13% and 13%, respectively. When the original stent was a DES the risk of a re-restenosis after the new invasive treatment was higher compared to treatment of BMS-ISR, HR (95% CI) 1.80 (1.59-2.03), p<0.001, Figure 3.

Figure 1. Flow chart of the investigated population. BMS: bare metal stent; DEB: drug-eluting balloon; DES: drug-eluting stent; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; POBA: plain old balloon angioplasty

Figure 2. Cumulative crude incidence of re-restenosis for different ISR treatment alternatives independent of original stent type during five years of follow-up. BMS: bare metal stent; DEB: drug-eluting balloon; DES: drug-eluting stent; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

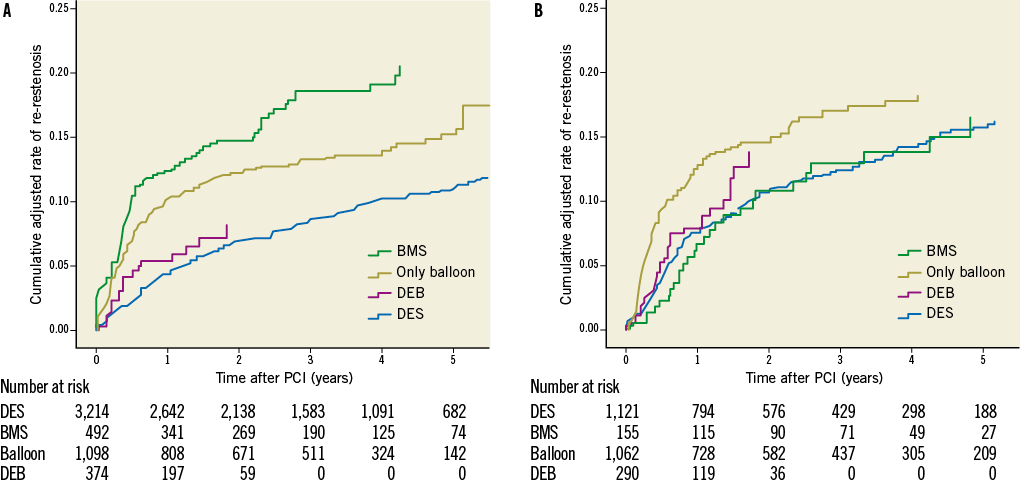

The effects of different ISR treatments are shown in Table 2. Table 3 shows the results when analysing treatment results of only one ISR per patient. With DES treatment of ISR, independent of initial stent type, the unadjusted and adjusted risk of new restenosis was lower as compared with treatment with BMS and with balloon angioplasty. Treatment with DEB had a lower risk of a re-restenosis than BMS, but not statistically different as compared with balloon angioplasty. There was also a trend towards a lower risk of re-restenosis for balloon angioplasty compared to BMS. In the statistical model, a significant interaction was found between the type of original stent (DES/BMS) and the type of ISR treatment, p=0.032. The crude incidence of re-restenosis dependent on the original stent type is shown in Figure 3, and the cumulative adjusted risk of re-restenosis for the two types of original stent (DES and BMS) and for the four major different ISR treatments separately are shown in Figure 4A and Figure 4B. Treatment results of BMS-ISR differ largely in contrast to DES-ISR. When comparing “old DES” (n=2,921) vs. “new DES” (n=1,422) no significant statistical difference was found, HR (95% CI) 0.85 (0.66-1.10), p=0.213.

Figure 3. Cumulative crude incidence of re-restenosis when the original stent was a drug-eluting stent or a bare metal stent, respectively, independent of treatment modality for the second intervention during five years of follow-up. BMS: bare metal stent; DES: drug-eluting stent; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

BMS-ISR

In BMS-ISR new treatment with a DES was associated with a significantly lower risk of re-restenosis, compared to both balloon angioplasty and BMS. The risk was more than halved when a DES was used compared to a BMS. For balloon angioplasty the risk of a subsequent new restenosis was lower compared to novel BMS implantation. For DEB the adjusted incidence was significantly lower as compared to a new BMS and in the unadjusted model as compared to balloon angioplasty. However, after adjustment this statistically significant difference disappeared.

DES-ISR

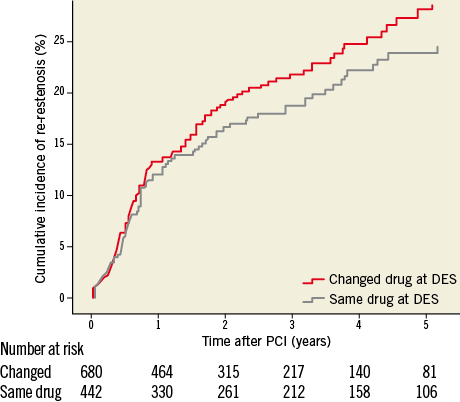

In the treatment of DES-ISR the only statistically significant difference was a lower risk of re-restenosis with novel DES implantation compared to balloon angioplasty. There were no differences in re-restenosis rates among the use of DES, BMS and DEB compared to each other in DES-ISR. In 1,122 cases the DES-ISR was treated with a new DES. In these pairs of DES, 61% had the same drug on both stents and in 39% of pairs the drug on the new stent was different from the first one. The change of stent drug did not affect the risk of re-restenosis, HR (95% CI) 1.16 (0.88-1.53), p=0.290, and after adjustment 1.14 (0.084-1.55), p=0.391 (Figure 5). No statistical interaction was found between change of drugs and the type of drug used in the DES, p=0.831.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the long-term outcome after treatment of ISR with different types of interventional therapy in a very large cohort of unselected, consecutive patients from all interventional centres in Sweden. Patients with ISR presented in 67% with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), while 18.3% presented with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, emphasising again the severity of the disease.

In the study period we encountered a variety of different interventional therapies with different outcome. In general, there was a good effect of PCI treatment of restenosis: in about 85-90% of the lesions there was no reporting of a new restenosis during the first year. However, we found a considerable difference in the risk of re-restenosis between the two types of the original stents. When the original stent was a DES, the risk of re-restenosis was 1.8 times higher than if the original stent was a BMS. Thus, when a restenosis occurs in a DES (which is a rarer event compared to restenosis in BMS), there is a higher risk for re-restenosis13.

BMS-ISR

Drug-eluting devices showed good results in BMS-ISR (Figure 4A) with a reduction of the risk of a new restenosis for both DES and for DEB compared to novel BMS implantation. Also, compared to balloon angioplasty, drug-eluting devices had a better effect, significantly so for DES versus balloon angioplasty but only as a trend when DEB was compared to balloon angioplasty. The only randomised controlled trial comparing novel BMS implantation to balloon angioplasty in the treatment of BMS-ISR showed that the binary restenosis rate and the one-year event-free survival rate were similar in both groups16. In our study balloon angioplasty had a better effect than using a new BMS in BMS-ISR. Similarly, in an earlier observational study17, BMS did not reduce TLR or death at one year compared to balloon angioplasty in the treatment of BMS-ISR. Our study shows the lower clinical need for reintervention after use of drug-eluting devices for the treatment of BMS-ISR, as has been described previously14,18,19. In a recent retrospective trial for the treatment of BMS-ISR18, DES were associated with a significantly lower composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, MI or TLR when compared to BMS at 3.2 years of follow-up (21% versus 45%, p=0.03).

Figure 4. A) Cumulative adjusted risk of re-restenosis for different treatment of restenosis when the original stent was a bare metal stent during five years of follow-up. B) Cumulative adjusted risk of re-restenosis for different treatment of restenosis when the original stent was a drug-eluting stent during five years of follow-up. BMS: bare metal stent; DEB: drug-eluting balloon; DES: drug-eluting stent; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

The DEB technique represents a new treatment alternative. First data in randomised controlled trials showed favourable results in the treatment of BMS-ISR compared to balloon angioplasty20 and paclitaxel-eluting stents21.

DES-ISR

While DES use is an effective treatment for patients with BMS restenosis, the same cannot be said for patients with DES restenosis. In our study the adjusted risk of new restenosis in a DES-ISR is higher compared to the risk of new restenosis after treatment of a BMS-ISR. Patients with DES-ISR experience significantly higher rates of target vessel revascularisation (TVR) (10.3% BMS-ISR vs. 22.2% DES-ISR, p=0.0113, 19.7% BMS-ISR vs. 27.8% DES-ISR, p=0.0522) with trends towards increased major adverse clinical endpoint (MACE) rates (16% BMS-ISR vs. 25.2% DES-ISR, p=0.0813, 24.3% vs. 32.5%, p=0.0622) in studies on 23813 and 2,148 patients22. Many observational studies have evaluated outcomes after PCI for DES-ISR, but numbers of enrolled patients have been too small and results too inconsistent to draw definitive conclusions about the optimal treatment of DES-ISR23. Data of the Japanese j-Cypher registry, evaluating 1,094 sirolimus-eluting stent (SES) ISR, comparing re-SES therapy versus balloon angioplasty, showed significantly lower TLR rates in the re-SES cohort (23.8% vs. 37.7%, p<0.0001), without differences in two-year mortality24. Smaller randomised trials11,12 showed superiority of the DEB compared to plain balloon dilatation in patients with DES-ISR on 13111 versus 5012 patients. This fact could not be confirmed in our study including 290 DEB-treated DES-ISR. Compared to balloon angioplasty none of the three major treatment options (re-DES, BMS or DEB) showed superiority. Only after adjustment, using multivariate regression analysis, did the implantation of a second DES become statistically significantly better than balloon angioplasty in the treatment of DES-ISR. Compared to BMS implantation in a DES-ISR, neither re-DES nor DEB therapy showed superiority. Our analysis showed that the implantation of a second DES carrying a drug different from the one that was used before does not show any advantage compared to the application of a DES with the same drug again (Figure 5), which is in accordance with most25,26 but not all27 data in the literature.

Figure 5. Cumulative adjusted risk of re-restenosis for treatment of restenosis when the original stent was a drug-eluting stent and the drug on the second drug-eluting stent was of the same type or different during five years of follow-up. DES: drug-eluting stent; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

In our registry analysis, treatment groups were heterogenous. In the DES group different types of first and second-generation stents were used, and in the DEB group four different types of drug-coated balloons were evaluated. According to a recent investigation28, efficacy varies largely among the different devices. In our study, 14% of the DEBs used belonged to the type of DEB with the lowest efficacy, which may have had a negative impact on the restenosis rate.

Limitations

The inherent limitations of a non-randomised registry study should be acknowledged. The findings should be regarded as hypothesis-generating. Despite appropriate statistical adjustments, unknown confounders may have affected the results. Moreover, it is not possible to attribute individual events to the individual stents or the stented vessel. Some patients presenting with ISR could not be followed up because the previously treated segment was renamed on a later occasion. Patients with clinically relevant ISR who underwent bypass surgery or were treated medically were also not studied.

The pattern of restenosis (focal/non-focal) has an important impact on the treatment result, but these data are currently not available in the SCAAR database. The choice of stent type was based on the operator’s decision, which could possibly have introduced selection bias. Since we did not differentiate the pattern of restenosis, acute stent thrombosis may also have been falsely coded as restenosis by the operator in a few cases, possibly explaining the relatively high number of patients with STEMI. However, there is also evidence that a severe restenosis may present with acute stent occlusion and ST elevation.

Funding

Supported by funds from the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions and the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation (to SCAAR and the Uppsala Clinical Research Center) and by a grant from the Swedish Board of Health and Welfare and the Swedish Medical Products Agency (all Stockholm, Sweden).

Conflict of interest statement

S. James has received institutional research grants from Medtronic, Terumo Inc., and Vascular Solutions, and has received honoraria for advisory board work with Medtronic. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.