Abstract

Aims: In patients with aortic stenosis randomised to transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) or surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), sex-specific differences in complication rates are unclear in intermediate-risk patients. The purpose of this analysis was to identify sex-specific differences in outcome for patients at intermediate surgical risk randomised to TAVI or SAVR in the international Surgical Replacement and Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (SURTAVI) trial.

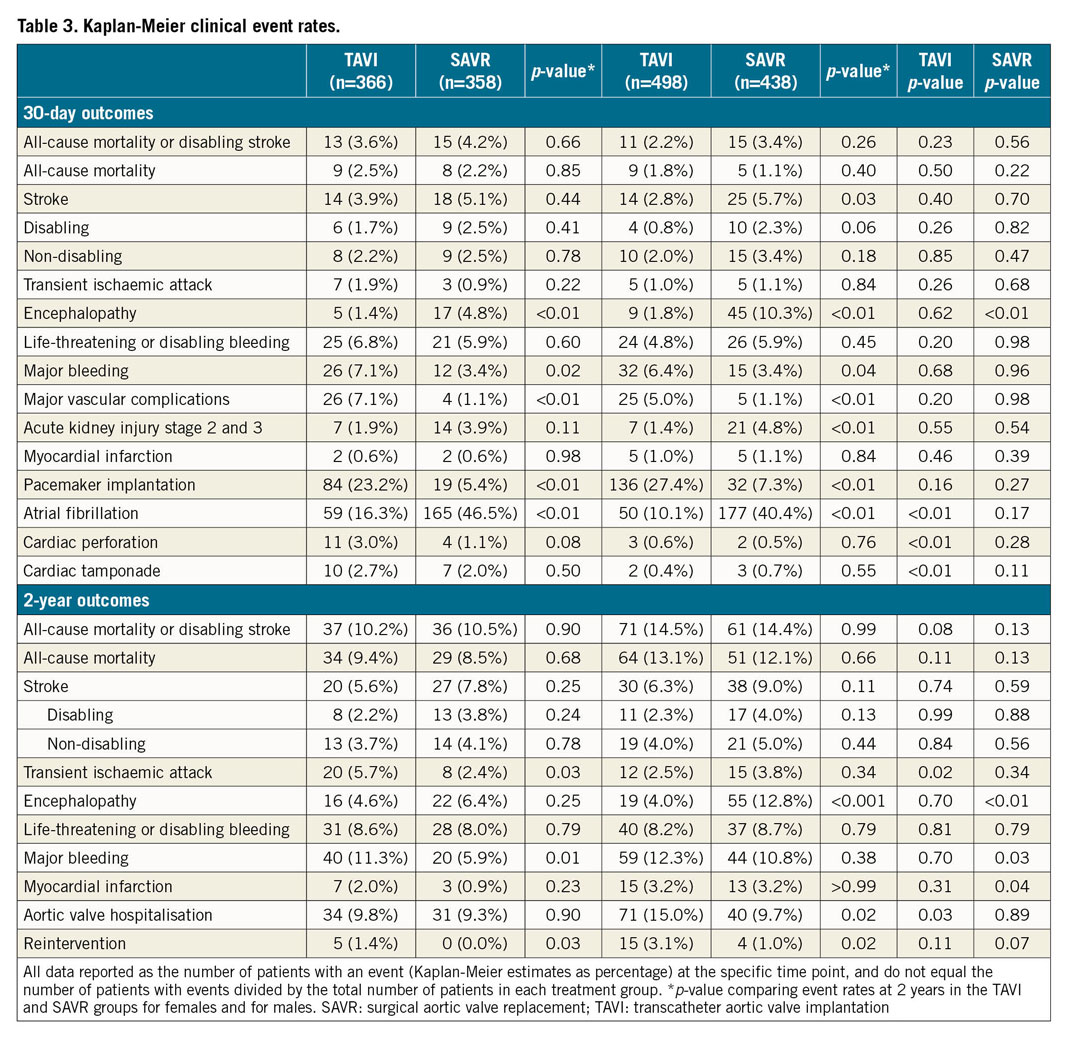

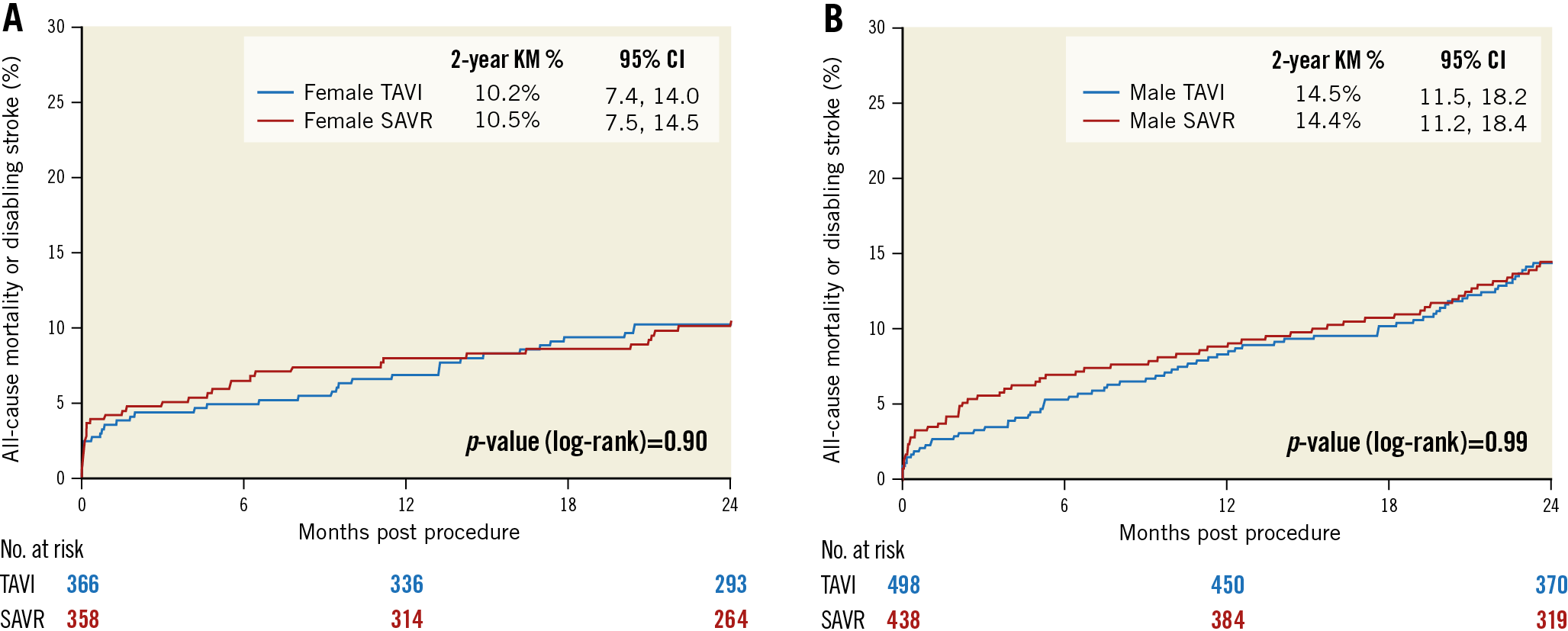

Methods and results: A total of 1,660 intermediate-risk patients underwent TAVI with a supra-annular, self-expanding bioprosthesis or SAVR. The population was stratified by sex and treatment modality (female TAVI=366, male TAVI=498, female SAVR=358, male SAVR=438). The primary endpoint was a composite of all-cause mortality or disabling stroke at two years. Compared to males, females had a smaller body surface area, a higher Society of Thoracic Surgeons score (4.7±1.6% vs 4.3±1.6%, p<0.01) and were more frail. Men required more concomitant revascularisation (23% vs 16%). All-cause mortality or disabling stroke at two years was similar between TAVI and SAVR for females (10.2% vs 10.5%, p=0.90) and males (14.5% vs 14.4%, p=0.99); the difference between females and males was 10.2% vs 14.5%, for TAVI (p=0.08) and 10.5% vs 14.4%, SAVR (p=0.13). Functional status improvement was more pronounced after TAVI in females than in males.

Conclusions: Aortic valve replacement, either by surgical or transcatheter approach, appears similarly effective and safe for males and females at intermediate surgical risk. Functional status appears to improve most in females after TAVI. Clinical Trial Registration: http://clinicaltrials.gov NCT01586910

Introduction

Female sex is a risk factor for mortality after surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) according to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons predicted risk of mortality (STS-PROM) calculator and was associated with procedural mortality for SAVR but not transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) in the Italian Observational Multicenter Registry (OBSERVANT)1. In previous studies, TAVI appeared to have a favourable efficacy and safety profile compared to SAVR, particularly in females at high operative risk2,3,4. An analysis from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Therapy (TVT) Registry and a meta-analysis of 17 studies confirmed a lower one-year mortality after TAVI in females than males, despite more procedure-related complications5,6,7. However, in a large registry evaluating a balloon-expandable transcatheter valve in patients at intermediate and high operative risk, there was no difference in longer-term outcome between males and females8.

The purpose of this analysis was to identify sex-specific differences in outcome for patients at intermediate surgical risk randomised to TAVI or SAVR in the international Surgical Replacement and Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (SURTAVI) trial.

Methods

STUDY DESIGN

The SURTAVI trial9 randomised 1,746 patients with symptomatic, severe aortic stenosis (AS) deemed to be at intermediate risk for surgery in a 1:1 ratio to TAVI with a self-expanding valve (CoreValve® or Evolut™ R device; Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) or SAVR. Study design, detailed methods and primary results have been published3. For this sub-analysis, each treatment arm was stratified by sex, and clinical outcomes up to two years were compared. The trial complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, all local ethics committees approved the research protocol and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

ENDPOINTS

The primary endpoint was the composite of all-cause mortality or disabling stroke at two years. All endpoints were defined according to the Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 (VARC-2) criteria10. Rehospitalisation for aortic valve-related issues was defined as hospitalisation for aortic valve dysfunction or worsening heart failure. Additional outcomes included quality of life assessed with the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ)11, and exercise capacity measured by the six-minute walk test (6MWT)12. An echocardiographic core laboratory (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA) analysed echocardiograms for total aortic regurgitation (AR), mean aortic valve gradient (AVG), and effective orifice area (EOA). Patient-prosthesis mismatch (PPM) was defined per VARC-2 guidelines as moderate when the indexed EOA (EOAi) was 0.65-0.85 cm2/m2 and severe when the EOAi was <0.65 cm2/m2 in patients with a body mass index (BMI) <30 kg/m2; however, in those patients with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2, an EOAi of 0.60–0.70 cm2/m2 defines moderate PPM and an EOAi <0.60 cm2/m2 defines severe PPM13.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Categorical variables were compared between groups (either male vs female, or TAVI vs SAVR) using the χ² or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables are presented as mean±standard deviation and compared between groups using the independent samples t-test. Kaplan-Meier estimates were used to construct the graph of all-cause mortality or disabling stroke for the time-to-event analysis. Clinical event rates were calculated using Kaplan-Meier analysis. The log-rank test was used to compare the event time distributions between groups. All testing used a two-sided alpha level of 0.05. Missing data were not imputed. Subjects with missing data were not included in corresponding portions of the analysis. Cox proportional hazard regression was used to evaluate predictors of two-year all-cause mortality separately within the male and female cohorts. Covariates included treatment (TAVI or SAVR) and select baseline characteristics (age, STS score, NYHA III/IV vs I/II, need for revascularisation, average 5-metre gait speed >6 seconds or wheelchair bound, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, prior stroke, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation or flutter, and moderate or severe chronic lung disease). Hazard ratios (HRs), two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p-values from the multivariable model are presented. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

PATIENTS

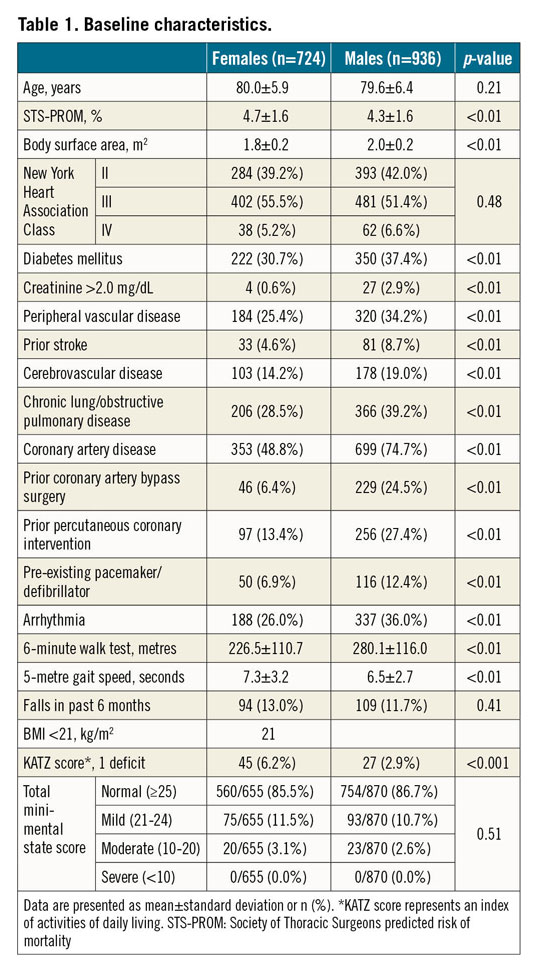

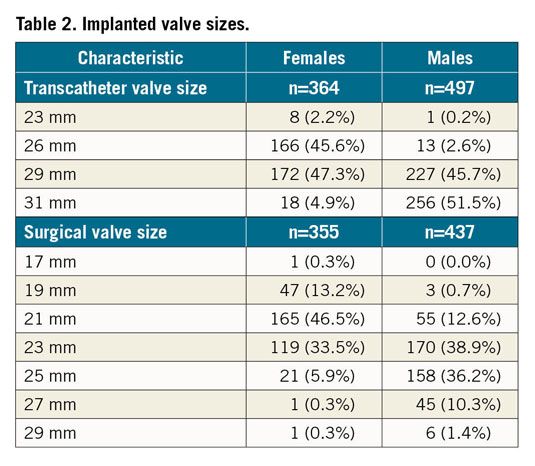

Relative to males, females were at higher risk according to STS-PROM (4.7±1.6% vs 4.3±1.6%; p<0.01) but had fewer comorbidities. Females had smaller body surface areas and more frailty indicators (Table 1). The baseline characteristics were balanced between TAVI and SAVR between the sexes (Supplementary Table 1). A total of 116/724 (16%) females underwent concomitant coronary revascularisation versus 216/936 (23%) males. Females received smaller-sized valves than males (Table 2).

EARLY CLINICAL OUTCOMES

All-cause mortality at 30 days was similar between treatment arms for each sex (females: SAVR 2.2%, TAVI 2.5%; p=0.85; males: SAVR 1.1%, TAVI 1.8%; p=0.40). There was no significant difference in mortality between males and females in the TAVI (p=0.50) or SAVR (p=0.22) arms (Table 3). For males, the 30-day rate of stroke following SAVR was significantly higher than TAVI (SAVR 5.7%, TAVI 2.8%; p=0.03), but not for females (SAVR 5.1%, TAVI 3.9%; p=0.44). There was no significant difference in the rate of stroke between males and females in the TAVI (p=0.40) or SAVR (p=0.70) arms.

In the TAVI arm, females experienced significantly more atrial fibrillation, cardiac perforation, and cardiac tamponade than males (atrial fibrillation: females 16.3%, males 10.1%; p<0.01; cardiac perforation: females 3.0%, males 0.6%; p<0.01; cardiac tamponade: females 2.7%, males 0.4%; p<0.01) (Table 3).

CLINICAL OUTCOMES AT TWO YEARS

The primary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality or disabling stroke at two years for females was 10.5% for SAVR and 10.2% for TAVI (p=0.90) (Table 3, Figure 1A). For males, the rate was 14.5% for TAVI and 14.4% for SAVR (p=0.99) (Table 3, Figure 1B). There was no difference in the primary composite endpoint for males and females in TAVI (p=0.08) or SAVR (p=0.13). The rates of all-cause mortality were also similar for females (9.4% TAVI, 8.5% SAVR; p=0.68) and males (13.1% TAVI, 12.1% SAVR; p=0.66) with no difference in rates by sex in TAVI (p=0.11) or SAVR (p=0.13). There was no significant difference in the rate of stroke following SAVR or TAVI for either sex (females: SAVR 7.8%, TAVI 5.6%; p=0.25; males: SAVR 9.0%, TAVI 6.3%; p=0.13). Reintervention was more common following TAVI for both sexes (males: SAVR 1.0%, TAVI 3.1%; p=0.02; females: SAVR 0.0%, TAVI 1.4%; p=0.03). Males but not females in the TAVI group were rehospitalised for symptoms of heart failure or aortic valve dysfunction more often than those in the SAVR group. Males were rehospitalised more than females after TAVI (p=0.03).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier all-cause mortality or disabling stroke estimates. All-cause mortality or disabling stroke for females (A) and males (B) in the TAVI and SAVR groups.

PREDICTORS OF TWO-YEAR MORTALITY

Of the selected covariates, prior stroke was the only significant predictor of two-year mortality for females (HR 3.44, 95% CI: 1.51-7.83, p<0.01) while a history of atrial fibrillation or flutter was the only significant predictor for males (HR 1.60, 95% CI: 1.08-2.36, p=0.02). Treatment allocation (either TAVI or SAVR) was not associated with two-year mortality for males (p=0.75) or females (p=0.72) (Supplementary Table 2).

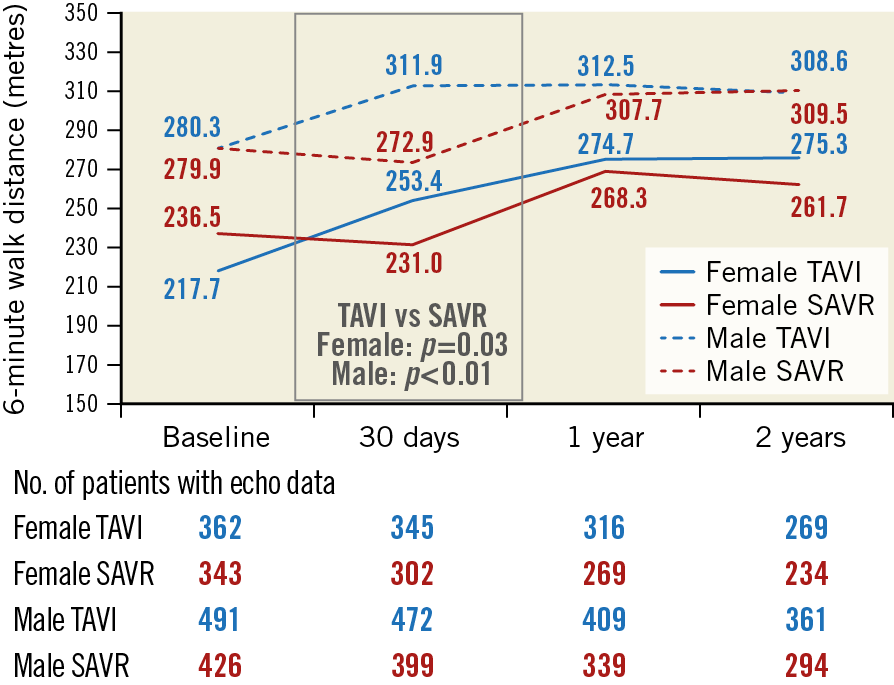

EXERCISE CAPACITY

At baseline, males walked a greater distance in six minutes than females (280.1±116 m vs 226.6±110.6 m, p<0.001) (Figure 2). At 30 days following TAVI, both sexes improved their average 6MWT distance by more than 30 metres relative to baseline. SAVR patients walked, on average, a shorter distance in six minutes at 30 days than they did at baseline. By one year, SAVR patients had improved their 6MWT distance relative to baseline in both sexes. Among the TAVI patients at one year, females had a more pronounced improvement than males (females: SAVR ∆23.1±97.9 m, TAVI ∆49.8±110.2 m; p<0.01; males: SAVR ∆13.7±105.1 m, TAVI ∆27.8±98.1 m, p=0.08). Distance walked remained similar between one and two years in all groups. For the TAVI cohort, the 6MWT improved more for females than males at two years (∆37.9±108.3 vs ∆18.7±119.6 m; p=0.06). Results were similar when only patients with data at each time point were included (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 2. Metres walked in 6 minutes relative to baseline. The average distance in metres walked at 30 days, one year, and two years relative to the average distance walked at baseline for males and females in the TAVI and SAVR groups.

QUALITY OF LIFE

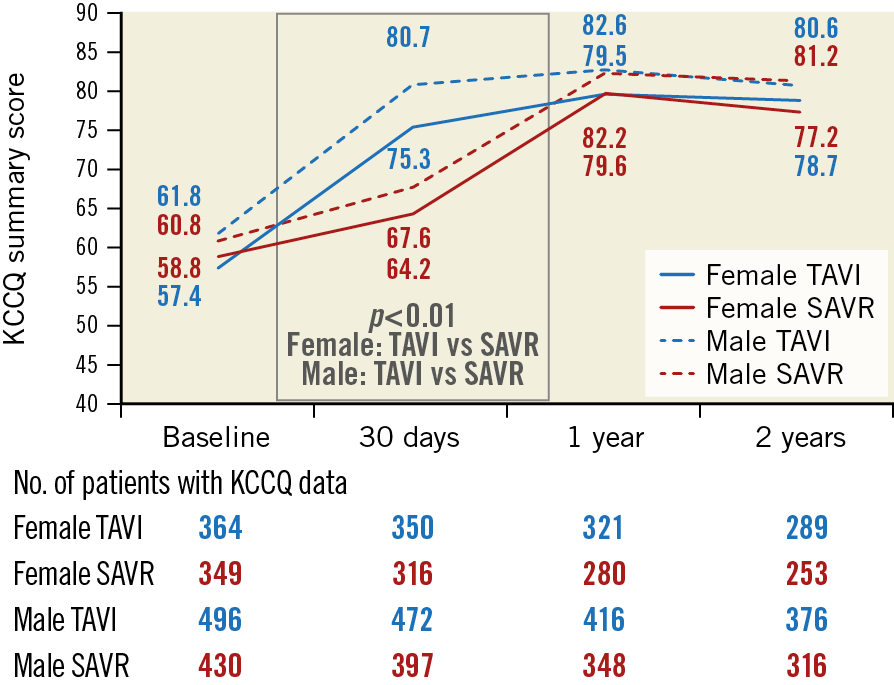

The KCCQ overall summary score improved faster after TAVI than SAVR and was similar between treatments at both one and two years for both sexes (Figure 3, Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 3. Mean KCCQ overall summary score from baseline to two years. Mean Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) overall summary score for females (solid lines) and males (dotted lines) in the TAVI (blue lines) and SAVR (red lines) groups.

ECHOCARDIOGRAPHIC FINDINGS

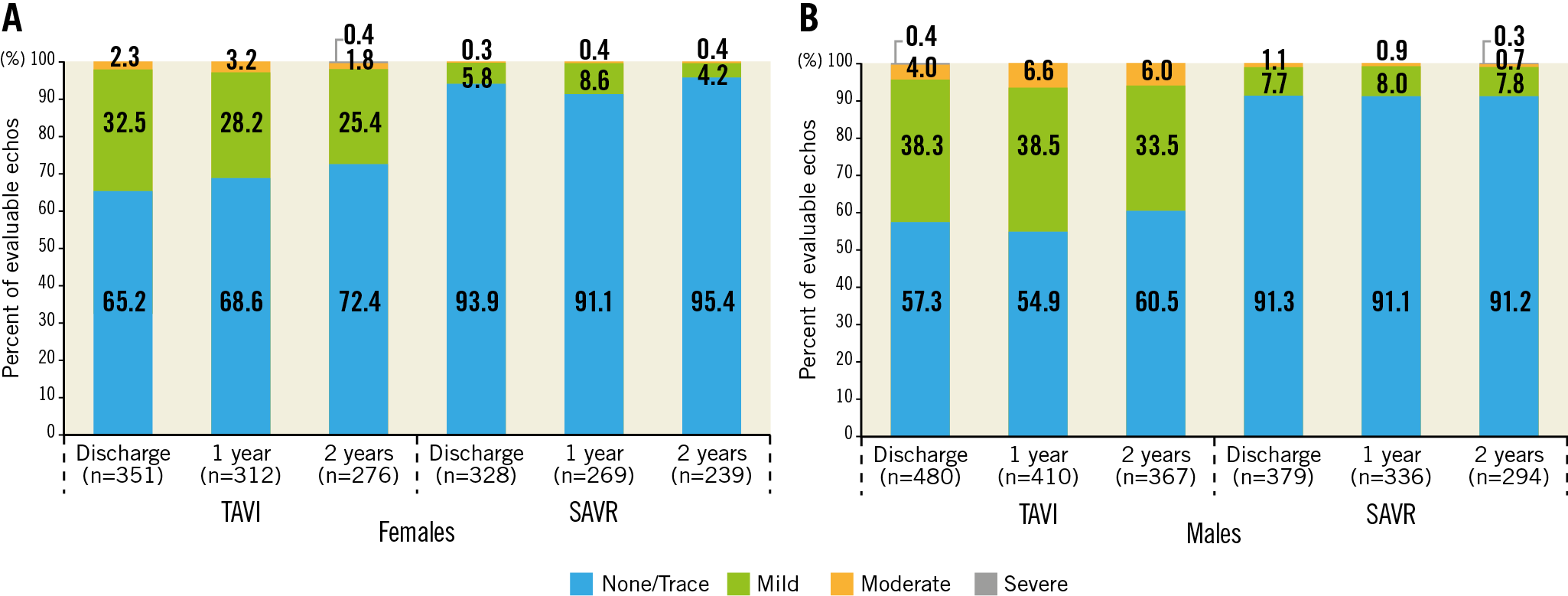

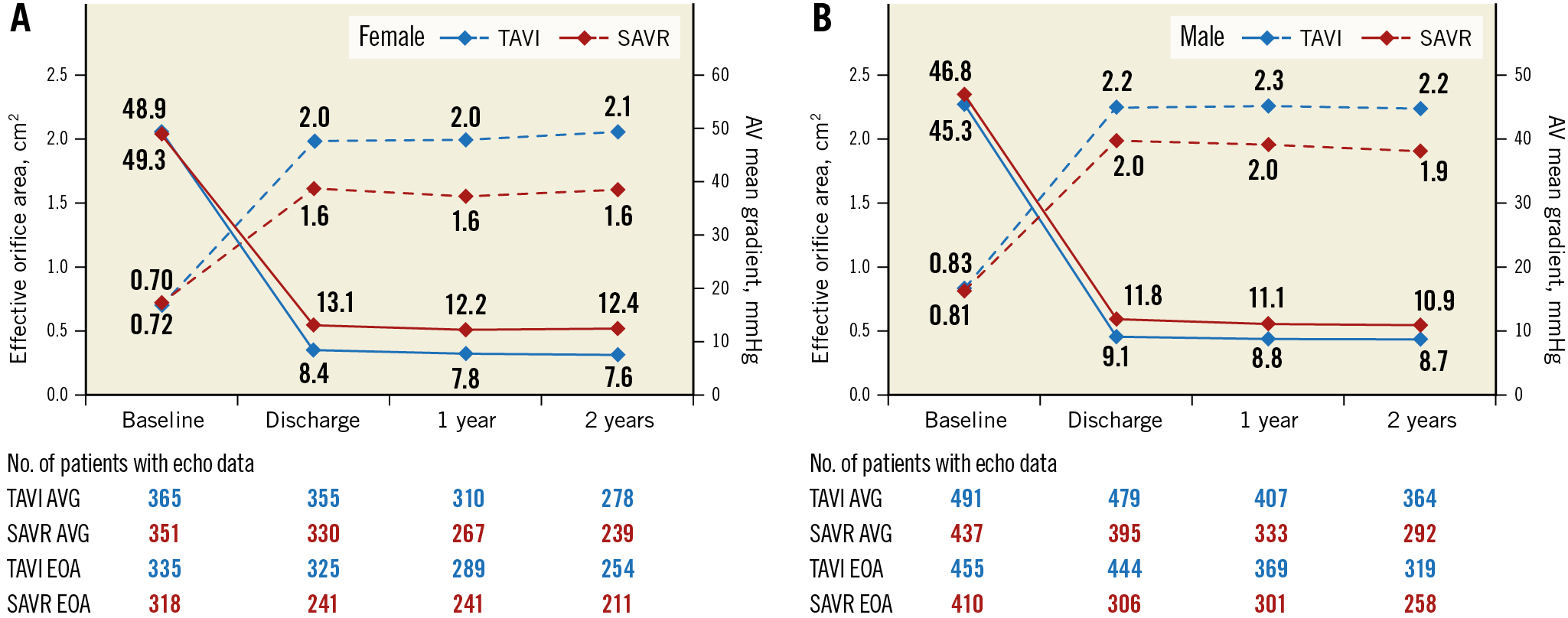

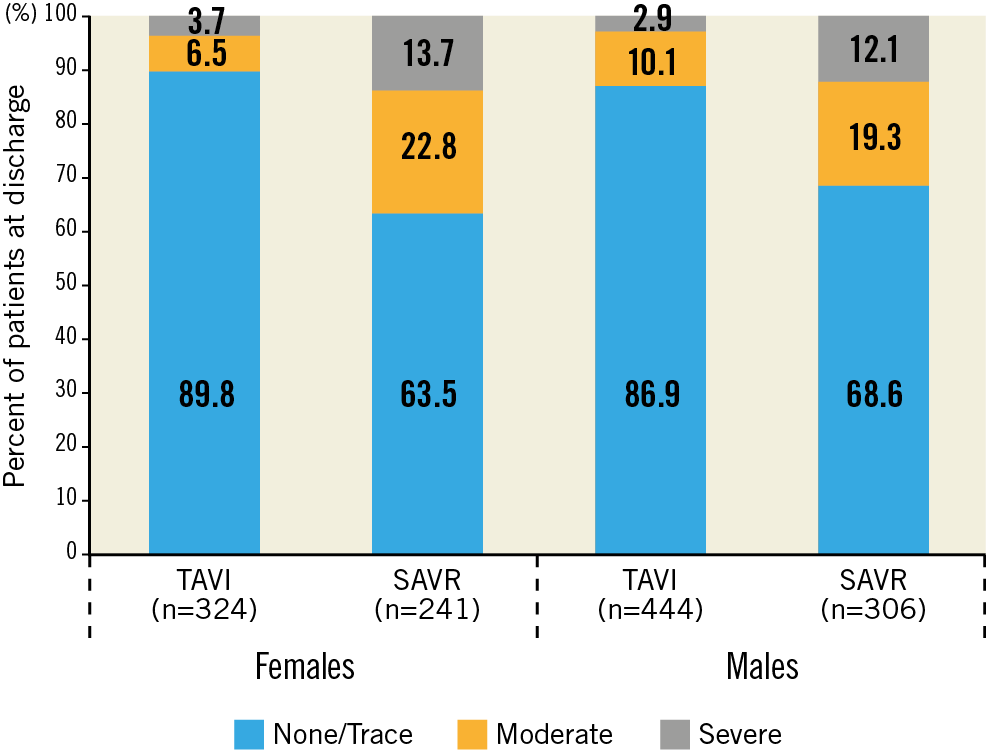

For both sexes, moderate or severe total AR was more frequent following TAVI than SAVR at discharge and up to two years (Figure 4A, Figure 4B, Supplementary Figure 3). More than mild PVL after TAVI occurred more often in males than females at all time points and reached statistical significance at two years (6% vs 2.2%, p=0.02). Both sexes experienced lower AVG and larger EOA (Figure 5A, Figure 5B, Supplementary Figure 4) and less severe PPM (Figure 6) at each follow-up time point following TAVI as compared to SAVR. There were no differences between males and females within each treatment arm.

Figure 4. Aortic regurgitation up to two years. Core lab reported total aortic regurgitation for females (A) and males (B) in the TAVI and SAVR groups.

Figure 5. Valve haemodynamics up to two years. Core lab reported effective orifice area (dotted lines) and aortic valve mean gradient (solid lines) over time for females (A) and males (B) in the TAVI (blue lines) and SAVR (red lines) groups. Transcatheter valve replacement was associated with significantly larger effective orifice area, and significantly smaller mean gradient at each time point compared with surgery (all p<0.01).

Figure 6. Patient-prosthesis mismatch at discharge. Moderate or severe patient-prosthesis mismatch at discharge was more common following SAVR for both males and females (both p<0.01).

Discussion

This post hoc analysis from the SURTAVI trial focused on sex-specific outcome differences and can be summarised as follows. 1) In elderly patients at intermediate operative risk, there are no sex-specific differences in the two-year rate of all-cause death or disabling stroke after TAVI using a self-expanding valve (CoreValve or Evolut R) or SAVR. 2) Concomitant coronary revascularisation was more common in males who have more comorbidities than females who are frailer. 3) Females had more TAVI procedure-related complications than males without any early or late survival penalty. 3) In general, females received smaller valve prostheses than males but there was no gender difference in PPM. 4) More than mild PVL after TAVI was more common in males than females. 5) Functional capacity improved more quickly with TAVI than SAVR in both sexes with a greater incremental improvement in females at 30 days and one year. 6) Rehospitalisation for valve or heart failure-related symptoms after TAVI was more frequent in males than in females and was more frequent compared to SAVR only in males.

Randomised trials and meta-analyses evaluating TAVI versus SAVR in AS patients at high operative risk suggested that females had a better clinical outcome with TAVI than SAVR. In the Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valve (PARTNER) 1 trial, females had lower two-year mortality particularly with transfemoral TAVI (23.4% vs 36.9%, p=0.023)4. The CoreValve US High Risk Pivotal Trial confirmed a lower one-year mortality in females with TAVI over SAVR (12.7% vs 21.8%, p=0.03)2. A report from the TVT Registry including 23,652 patients with a mean age of 82 years and STS score of 8±6 suggested superior one-year survival in females over males5. However, the PARTNER 2 S3 trial included patients at high (n=583) and intermediate (n=1,078) operative risk and could not find sex-specific differences in mortality or stroke8. The SURTAVI trial enrolled patients with an intermediate-risk profile and is aligned with the PARTNER 2 S3 trial. In lower-risk patients, a mortality difference between males and females after TAVI is not observed, and survival in females was similar for SAVR and TAVI.

Studies consistently report that female patients present with a higher predicted STS operative risk score, have less coronary artery disease but are deemed to be frailer. In a population at higher operative risk, the FRAILTY-AVR study confirmed that women presented with more physical frailty traits than men14. Females compared to males suffered more TAVI-related procedure complications, specifically more access-site complications and bleeding without any early mortality penalty. In this SURTAVI analysis, patients were at lower overall risk and TAVI was no longer associated with excess major vascular or bleeding complications in female patients, although we found more atrial fibrillation, cardiac perforation, and cardiac tamponade versus in male patients. Need for conversion to open surgery for ventricular or annular rupture was also higher in female patients in the TVT Registry5. Whether this finding is associated with frailty status and increased myocardial vulnerability in females remains speculative. However, 9 out of 13 women with TAVI-associated tamponade or ventricular perforation were frail as compared to 1 out of 4 men.

The consistent observation of a higher frequency of more than mild PVL after TAVI in male versus female patients remains incompletely understood. In the early TAVI experience, a potential hypothesis was the lack of larger transcatheter valve sizes resulting in more undersizing in males than in females4. Our data seem to refute this hypothesis because a broader range of transcatheter valve sizes was available to accommodate aortic annulus diameters between 18 and 30 mm. Despite more use of larger valve bioprostheses, a higher rate of more than mild PVL persisted in men. A prior report suggested that females compared to males presented with similar AS severity by echocardiography in terms of aortic valve area and peak aortic jet velocity but less aortic valve calcification measured by multidetector computed tomography15. Aortic root calcification has been linked to PVL16. Excessive calcium in the aortic root may preclude complete transcatheter valve deployment and induce valve eccentricity, particularly with a self-expanding design. Valve eccentricity seems to be associated with PVL17. One can speculate that the higher likelihood for PVL in males in SURTAVI at least partially explains the need for more rehospitalisations for valve or heart failure-related symptoms. It could also help to explain the more pronounced improvement in functional capacity measured by the 6MWT up to two years in females after TAVI.

Limitations

This report reflects a post hoc analysis of the SURTAVI randomised trial. SURTAVI was not powered to address sex-specific differences after TAVI or SAVR specifically. Our TAVI findings should be interpreted in the perspective of a self-expanding valve design. It is worth noting that the majority of TAVI procedures used the first-generation CoreValve system without advanced repositioning features, outer porcine tissue wrap and smaller profile. Device iterations may affect valve performance and clinical outcomes in males and females.

Conclusions

Aortic valve replacement, either by a surgical or transcatheter approach, is equally effective and safe for males and females at intermediate surgical risk. Functional status appears to improve most in females after TAVI.

|

Impact on daily practice Sex differences in clinical outcomes have been reported after transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) or surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) in patients with symptomatic, severe aortic stenosis at high operative risk. In an analysis of 1,660 intermediate-risk patients (724 females and 936 males) randomised to TAVI or SAVR, there was no difference in all-cause mortality or disabling stroke at two years between males and females receiving either treatment or between TAVI and SAVR in females or males. Functional status improvement was more pronounced after TAVI for females compared to males, but quality of life improvement was similar between the sexes and faster after TAVI than SAVR for all patients. |

Acknowledgements

Molly Schiltgen, MS, and Colleen Gilbert, PharmD, employees of Medtronic, assisted in preparation of the manuscript including drafting the Methods and Results sections, creating Tables and Figures, and ensuring the accuracy of the trial information. Shuzhen Li, an employee of Medtronic, provided statistical analyses.

Funding

This work was supported by Medtronic, plc (Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Conflict of interest statement

N. Van Mieghem has received research grants from Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences, and Abbott Vascular. M. Reardon has received fees from Medtronic for providing educational services. S. Yakubov has received institutional research grants from Boston Scientific and Medtronic. S. Windecker has received institutional research grants from Abbott, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, and Terumo. R. Makkar has received research grants from Edwards Lifesciences and St. Jude Medical, and personal fees from Abbott Vascular, Cordis, and Medtronic. P.W. Serruys has received grant support and fees from Medtronic, Philips, and ReCor Medical. J. Popma is an employee of (and reports other from) Medtronic. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.