Several investigators have reported favourable clinical outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI)1-7. These studies, however, are characterised by a great deal of heterogeneity involving the definition of clinical endpoints. Several organisations with an interest in TAVI have alluded to the need for standardising reporting practices8-11. The purpose of this editorial is to create awareness of the challenges associated with clinically assessing TAVI and, more importantly, to call for consistency among endpoint definitions used for reporting the results of transcatheter valvular interventions.

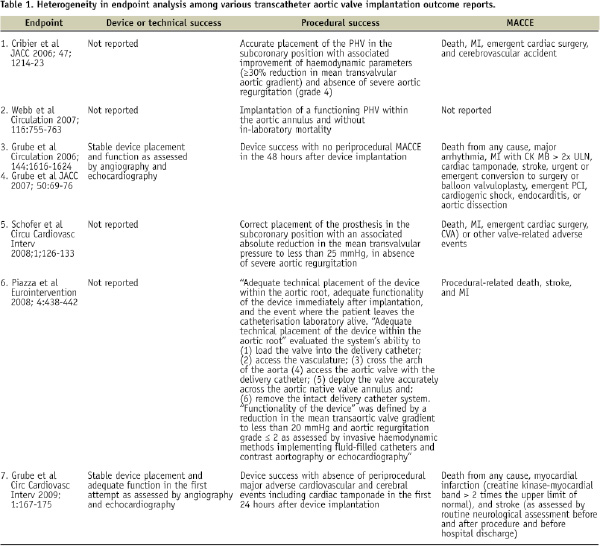

One complicating factor when trying to evaluate available data stems from the fact that the components of safety and efficacy have differed across TAVI studies. Some investigators include both device and procedural success, whereas others report only procedural success. Discrepancies also exist in how different research teams define these particular endpoints (see Table). From this table we can also appreciate the variations that exist for reporting major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE).

How are we to proceed? To make the best use of empirical knowledge, we can learn from the Academic Research Consortium (ARC) that developed a set of consensus definitions for coronary stent trials12. This informal collaboration between organisations in the United States and Europe acknowledged the mixed perspectives of physicians, regulatory bodies, and manufacturers. Therefore, the consortium enlisted academics, clinical trialists, device manufacturers, and representatives of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Two aspects of the group’s effort are of note: first, it was suggested that endpoint definitions should relate to overall device safety and effectiveness. Specifically, safety endpoints were meant to include any adverse event, whether device-related or not, and effectiveness was related to the effects of early and late relief of coronary obstruction (pathophysiological mechanism of action). Second, patient-oriented composite endpoints (e.g., all-cause mortality, any myocardial infarction [MI], and need for repeat revascularisation) were contrasted with device-oriented endpoints (cardiac death, MI, or repeat procedure) to highlight the patients’ perspective and capture the complex interplay between patient baseline characteristics, procedural factors, device performance, and possibly unrecognised factors affecting outcomes.

We may face as great or even greater challenges developing standardised reporting for TAVI. Some common ground for clinical endpoint reporting would be required to allow valid treatment comparisons between TAVI and surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR). The vast body of knowledge and experience of the cardiac surgeon in the field of valvular heart disease cannot be overstated. Recently, Akins et al published updated guidelines on the reporting of mortality and morbidity after cardiac valve interventions10. The authors of the guidelines included key experts in the field of cardiac surgery. Their updated document was intended to facilitate the analysis, reporting, and comparison of clinical studies of various therapeutic approaches to valvar heart disease, including TAVI. A closer examination of the guidelines would suggest that well-accepted definitions, such as structural and non-structural valve dysfunction and reintervention, would need reconsideration in order to make them more applicable to TAVI11. A heart team (specifically an interventional cardiologist and cardiac surgeon) would be best suited to address these issues13.

The benefits of standardised clinical endpoints are many, but primarily they allow for effective communication among all interested parties, including patients. To this end, they would serve both regulatory and clinical purposes. Moreover, comparisons and subsequent generalisations of studies would become more credible. Standardised definitions, however, would need to find sensible balance between being too liberal or too strict. Furthermore, they should be flexible enough to accommodate the rapidly changing technology and practice paradigms.

One question remains: Have we achieved a sufficient level of understanding of the benefits and risks associated with TAVI to begin discussions on the standardisation of clinical-endpoints? It is our opinion that it is time for a collaborative effort among interventional cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, regulatory bodies, and device manufacturers and that just such a consortium would provide the initial momentum to guide us in the right direction. The need for randomised controlled trials to adequately assess the outcomes of TAVI demands standardised definitions and the involvement of central core laboratories will be essential in their implementation.

Let us not make the same mistake as in stent trials - This editorial is a call for a Valvular Academic Research Consortium (VARC).

Acknowledgment

We would like to extend our appreciation to Dr. John Webb and Prof. Joachim Schofer for verifying the factual content of the information found in the table.