The evolution of stent technology has witnessed major breakthroughs during the past three decades. Early-generation drug-eluting stents (DES) releasing sirolimus (sirolimus-eluting stents [SES], e.g., CYPHER®; Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) or paclitaxel (paclitaxel-eluting stents [PES], e.g., TAXUS™; Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) reduced the risk of restenosis and repeat revascularisation compared with bare metal stents (BMS). However, the improved efficacy was offset by the increased risk of very late stent thrombosis (ST) and delayed repeat revascularisation owing to impaired arterial healing and neoatherosclerosis attenuating the risk-benefit profile during longer-term follow-up. The Endeavor® zotarolimus-eluting stent (E-ZES) (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was one not-able exception among early-generation DES as it performed more like BMS, i.e., less effective but also less prone to very late ST. More recently, new-generation DES featuring thin/ultrathin metallic platforms using cobalt-/platinum-chromium alloys, more biocompatible biodegradable and durable polymers for drug release, and limus analogues as antiproliferative drugs have combined improved efficacy and safety, as summarised in a systematic review1 and a recent individual patient data meta-analysis comparing new-generation DES with BMS2.

In parallel with advances in stent technology, clinical trial methodology has evolved remarkably with inclusion of all-comer patient populations in randomised clinical trials, the implementation of registry-based nationwide randomised clinical trials3, and the completion of systematic long-term follow-up. The latter is important to determine whether device-related adverse events such as stent thrombosis (ST) and repeat revascularisation have time-dependent profiles, which in turn may affect the duration and intensity of ancillary medical therapy. While most trials report outcomes up to five years, several studies have provided long-term follow-up up to 10 years including SYNTAX4, SIRTAX5, and SORT OUT II6. It is in this context that the SORT OUT III7,8 investigators report on extended findings of SORT OUT III up to 10 years in this issue of EuroIntervention9.

Previous evidence has established that the E-ZES was less effective compared to the SES10 during midterm follow-up owing to increased neointimal hyperplasia, related to the fast drug elution of 95% within two weeks.

Similarly, the PROTECT trial comparing E-ZES and SES in 8,791 patients reported lower efficacy in terms of target lesion revascularisation (TLR) up to four years. However, this trial, powered for the primary endpoint definite or probable ST, showed a lower risk of ST and myocardial infarction (MI) without significant differences in overall mortality up to four years11.

In the SORT OUT III trial7,8, which randomly allocated 2,332 patients (45% acute coronary syndrome) to either E-ZES (n=1,162) or SES (n=1,170), at 10 years there were no significant differences in the composite of all-cause death or MI, and in the individual endpoints all-cause death, MI or coronary revascularisation. This is in contrast to the 18-month results, where all-cause death and MI were less frequent with SES7, but corroborates the five-year results with no significant differences in these respective endpoints between E-ZES and SES8. Landmark analyses between five and 10 years show similar results for the composite of all-cause death and MI, as well as all-cause death, MI and coronary revascularisation.

The limitations of SORT OUT III relate to the absence of device-specific outcome data including ST and TLR (not collected beyond five years), precluding firm conclusions in terms of between-device comparisons. Likewise, the study does not add novel aspects on time-related changes in rates of ST and TLR. This would have been a relevant insight from this 10-year follow-up, as landmark analyses obtained have shown significantly higher rates of ST and TLR with E-ZES during the first year, but lower respective rates with E-ZES compared to SES at >1-5 years8.

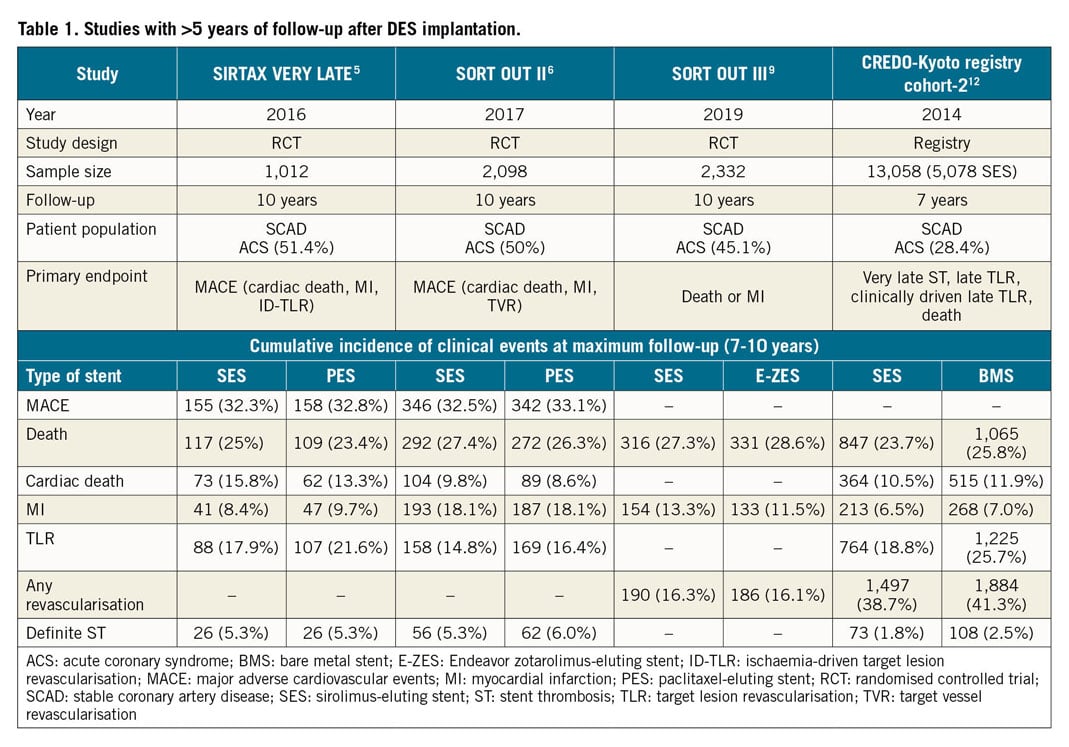

Currently available studies with >5-year follow-up after DES implantation are summarised in Table 1. The three RCTs show relatively consistent rates of death (23.4-28.6%). Rates of MI range from 11.5-18.1% within the SORT OUT trials6,9, whereas SIRTAX VERY LATE5 showed somewhat lower rates (8.4-9.7%).

Several insights can be derived from these extended follow-up reports:

1. Differences between early-generation DES in terms of repeat revascularisation (efficacy) during the first year of follow-up are offset during midterm follow-up up to five years with no further differential emerging up to 10 years.

2. Repeat revascularisation remains frequent and one of the principal reasons for inferior outcomes comparing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) in patients with advanced three-vessel coronary artery disease.

3. It is noteworthy that cardiovascular mortality contributed to only approximately 50% of all-cause mortality. The latter observation corroborates previous insights that cardiovascular mortality continues to decline relative to non-cardiovascular mortality and contributes to the diminished impact of cardiovascular therapies on all-cause mortality.

New-generation DES have overcome the limitations of both BMS and early-generation DES. Long-term follow-up has been firmly established in the evaluation of coronary devices. However, any device difference beyond five years will be increasingly difficult to establish in view of competing non-coronary risk factors and is futile as long as the progress in device iterations is maintained.

Conflict of interest statement

S. Windecker reports research and educational grants from Abbott, Amgen, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, BMS, Bayer, CLS Behring, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Polares and Sinomed. L. Räber received research grants to the institution from Abbott Vascular, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, HeartFlow, Sanofi and Regeneron, and speaker or consultation fees from Abbott Vascular, Amgen, AstraZeneca, CSL Behring, Occlutech, Sanofi and Vifor. The other author has no conflicts of interest to declare.