A 46-year-old male, current smoker, admitted for an inferior ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), received thrombectomy and Absorb BVS implantation in the mid right coronary artery with a good angiographic result. Although he was pre-treated with a loading dose of clopidogrel (600 mg per os), a loading dose of prasugrel (60 mg) was also administered at the end of the procedure.

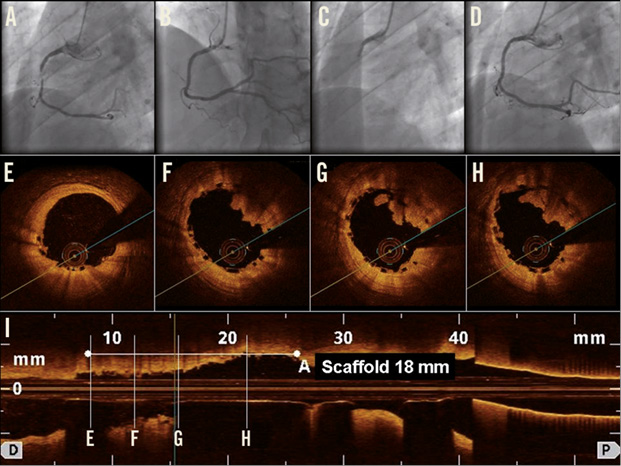

Two hours later, the patient presented with a scaffold thrombosis. After thrombectomy and abciximab administration, TIMI flow 3 was restored. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) did not show any mechanical causes and only post-dilatation was performed (Figure 1). The patient remained event-free at 30 days.

Figure 1. (A) Angiography showed a ruptured plaque in the mid right coronary artery successfully treated by Absorb BVS 3.0×18 mm (16 atm). (B) After acute scaffold thrombosis, (C) thrombectomy and post-dilation with 3.25 mm non-compliant balloon (20 atm) were performed with an optimal result. (D) OCT, performed after thrombectomy, showed large residual thrombus in the absence of mechanical thrombosis causes (E-I).

This case is the first description of scaffold thrombosis in a STEMI setting in the absence of mechanical causes, where post-dilation was chosen as the therapeutic strategy, aimed at optimising the scaffold size and then avoiding metallic stenting (Online data supplement).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Appendix. Explanatory comments on the acute Absorb scaffold thrombosis

Some concerns have been raised about Absorb bioresorbable vascular scaffold (BVS) thrombosis in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients. Jaguszewski et al reported the first case of an acute Absorb BVS thrombosis in an 80-year-old male admitted for ACS, probably due to scaffold malapposition according to optical coherence tomography (OCT) findings. The authors therefore recommended the use of OCT in cases of bioresorbable scaffold thrombosis in order to investigate possible mechanical causes1. In our case, the OCT analysis did not show any coronary spasm, dissection at the scaffold edges, strut malapposition or other possible mechanical causes of the scaffold thrombosis. High thrombogenicity of the scaffold or patient resistance to antiplatelet drugs may hypothetically be possible causes2-4. In this regard, early administration of Gp IIb/IIIa inhibitors could be helpful to prevent scaffold thrombosis, as previously noted with drug-eluting or bare metal stents5.

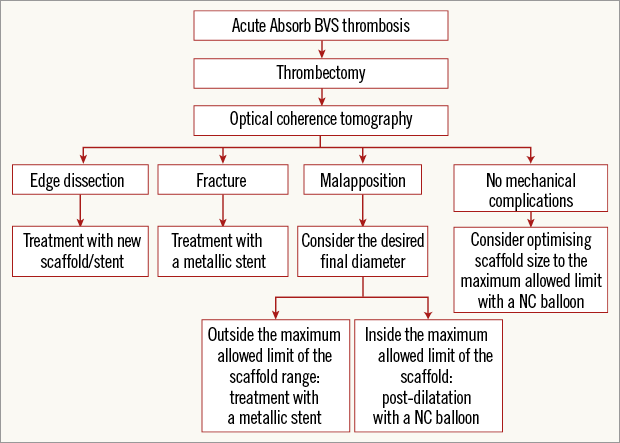

Another important point in scaffold thrombosis is whether or not it should be treated with metallic stent implantation1. It is known that treatment of a metallic stent thrombosis with implantation of a new metallic stent may enhance the thrombotic milieu and recreate the environment for a new stent thrombosis6. In case of bioresorbable scaffold thrombosis, the operators could be tempted to cover the thrombosis with the implantation of a metallic stent. In the clinical case reported by Jaguszewski, a 3.5×18 mm scaffold thrombosis, which was related to strut malapposition, was treated by thrombectomy and implantation of a 3.5×28 mm metallic stent, post-dilated by a 3.5 mm non-compliant (NC) balloon1. In our report, a post-dilation with a 3.25 mm NC balloon was the preferred therapeutic option, aimed at optimising the scaffold size. With this strategy, the thrombosis was successfully treated and the implantation of a metallic stent inside the scaffold was avoided.

In our opinion, treatment of scaffold thrombosis by metallic stent implantation should be reserved for those cases of OCT-documented scaffold fracture, or when, in case of malapposed struts, the operator wants to achieve a final diameter beyond the maximum recommended range of the Absorb BVS7. Another option could be to implant a new scaffold of larger diameter if the final desired diameter is beyond the recommended range of the scaffold which is thrombosed; however, the fact of having two scaffolds inside each other with a total thickness of 300 µm on each side of the vessel wall should be taken into account and in our opinion discouraged (Online Figure 1). Future trials to test Absorb in STEMI patients as well as an expert consensus are probably needed to understand the incidence of acute scaffold thrombosis and how to treat it.

Online Figure 1. Suggested flow chart for the treatment of acute Absorb BVS thrombosis. BVS: bioresorbable vascular scaffold; NC: non-compliant

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.