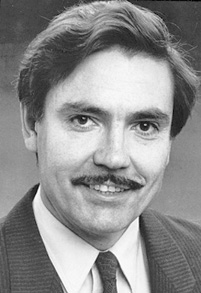

There are few areas in medicine where the development of an entire field is perceived to be so closely associated with one individual. Andreas Roland Grüntzig (Figure 1) was born in Dresden, Germany, ten weeks before the outbreak of the Second World War on 25 June 19391,2. After graduating from medical school in Heidelberg in 1969, he took a career-defining step by moving to the University Hospital in Zürich to take up a position in the Department of Angiology, which was chaired by Alfred Bollinger. In August 1971, after establishing himself in Zürich and inspired by an earlier lecture given by Eberhard Zeitler3 on the dilatation of peripheral arterial stenosis with rigid tubes pioneered by Charles Dotter4, he set off for a small town near Cologne to meet Zeitler and gain some hands-on experience with the technique. The two became friends, and subsequently together they performed the first “Dottering” case at the University Hospital in Zürich in late 1971. Grüntzig continued to accumulate experience with “Dottering” procedures over the coming years. Under the guiding influence of Wilhelm Rutishauser he became a cardiology fellow in 1973 and was appointed as a cardiologist in 1974.

Figure 1. Andreas Roland Grüntzig (1939-1985). Reproduced with permission from https://www.pcronline.com

At the same time, Grüntzig and others were well aware of the limitations of the rigid “Dottering” devices – including damage to the treated segment and distal embolisation – and their particular unsuitability in smaller vessels. With the help of Bollinger’s assistant, Maria Schlumpf, and her engineer husband, the three set about developing balloon angioplasty catheters over the course of the next three years. Working with polyvinyl chloride on Grüntzig’s kitchen table, initially they developed a single and then a double lumen balloon catheter, which allowed balloon inflation through one lumen and perfusion of the occluded artery through the other. The double lumen catheter was ultimately used for the first time to treat an iliac artery stenosis on 23 January 1975. Modifying the technique for use in coronary arteries began with the first dilatations of ligated canine coronary arteries on 22 October 1975. These initial cases were reported in the now famous abstract presentation at the American Heart Association meeting in Miami in November 19765. Also in the second half of 1976, the company subsequently known as Schneider Medintag began the commercial manufacture of the prototype balloon catheters. The final preparation for the first percutaneous coronary intervention was the proof of principle performance of the first dilatation of a coronary artery in a patient undergoing bypass surgery. This was performed through collaboration with Richard Myler in San Francisco on 9 May 1977.

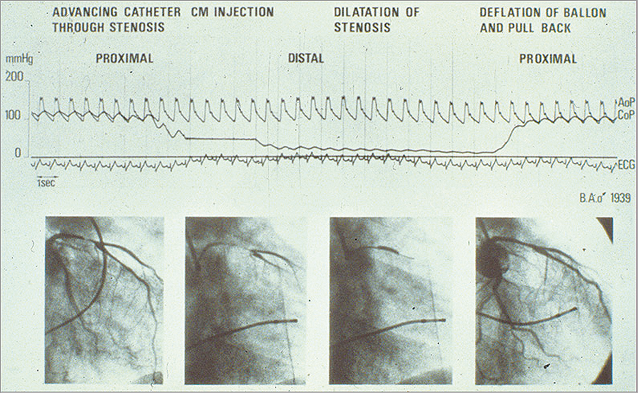

Meanwhile, the search continued for the first patient with a suitable lesion who was willing to undergo angioplasty. Back in Zürich, Bernhard Meier introduced Grüntzig to Adolf Bachmann – a 38-year-old man with debilitating angina and an accessible, focal proximal stenosis of the left anterior descending artery6. The patient had been scheduled for conventional revascularisation with bypass surgery but, after meeting Grüntzig, he agreed to be the first patient to undergo angioplasty7. On 16 September 1977, the patient underwent successful dilatation of his coronary stenosis by Grüntzig (Figure 2)8. A critical role was played by the renowned pioneering surgeon Ake Senning, who agreed to provide surgical back-up in case something went awry. The story of this remarkable case is now well known and was extensively documented in a recent article in these pages by Meier6 along with a video recording of a case demonstration by Grüntzig (Moving image 1). The rest of course is history, and developments over the intervening decades have seen percutaneous intervention become a cornerstone of the treatment of obstructive coronary artery disease. Bachmann remains alive and well 40 years later and you can watch a remarkable recording with him on the EuroIntervention website, in which he recounts his initial meeting with Grüntzig on the day before his bypass surgery was scheduled (Moving image 2).

Figure 2. Documentation of pressures during the world’s first coronary angioplasty on 16 September 1977 at the University Hospital of Zürich in Switzerland. The top curve represents the aortic pressure (AoP) at the tip of the guiding catheter in the coronary cusp. The bottom curve represents the pressure at the tip of the balloon catheter while in the coronary artery (CoP), damped because of the tiny lumen transmitting the pressure. The very low distal pressure during balloon occlusion (centre) documents the absence of collaterals. The distal pressure stayed practically level with the aortic pressure during balloon pullback at the end of the tracing. This testifies to a good haemodynamic result of angioplasty. The resolution of the cine frames depicted at the bottom is good, as these are pictures of the processed cine film not available during the intervention. The initials and year of birth of the patient are depicted at centre right. Reproduced with permission from Meier et al6. CM: contrast medium; ECG: electrocardiogram

In commemoration of the 40th anniversary of this first percutaneous coronary intervention, the current edition of EuroIntervention is devoted in its entirety to a review of the field. A series of eleven review articles focuses on the different aspects of percutaneous coronary intervention, showing how it has become one of the most frequently performed medical procedures in the world. This issue is released to coincide with the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) in Barcelona – which also has this anniversary as its central theme – and we are very pleased to include an interview with Stephan Achenbach, the chair of the ESC Congress Committee, as a foreword9. Those attending the congress in Barcelona will be able to visit a dedicated museum celebrating “40 years of angioplasty” organised by PCR located in Village 3. This museum already proved very popular with participants at EuroPCR 2017 in Paris earlier this year.

In the first three review papers in this issue, Carlos Collet and colleagues reflect on the equally remarkable story of the development of diagnostic coronary angiography10, Christos Bourantas and colleagues report on the development and progress in intravascular coronary imaging11, and Gianluca Pontone et al provide an overview of the state of the art in non-invasive imaging12. Invasive assessment of haemodynamic lesion severity is now an important part of routine clinical practice in patients with multivessel disease and lesions with unclear functional significance. Mauro Echavarria-Pinto provides a timely overview of this field in the light of recent important randomised clinical trials13.

The initial balloon angioplasty catheters of Grüntzig were rudimentary devices difficult to manoeuvre, placing all but the most proximal of lesions out of the reach of this pioneering intervention. Progress in balloon catheter technology was rapid with, amongst others, important advances by John Simpson, who developed a balloon catheter system allowing independent manipulation of the balloon catheter and guidewire14, and Tassilo Bonzel, who developed the monorail system for facilitating balloon catheter exchange15. Developments and the state of the art in balloon catheter technology are extensively reviewed by Fernando Alfonso and Bruno Scheller in a comprehensive article16. Emanuele Barbato et al review evolving concepts in plaque modification, particularly as it applies to the treatment of heavily calcified lesions17, and Giulio Stefanini and colleagues provide a comprehensive review of bare metal and drug-eluting stent technology18, the latter of which was a critical development in facilitating the expansion of percutaneous intervention to patients with complex disease patterns such as left main stem stenosis, coronary bifurcations, and multivessel disease. The widespread adoption of angioplasty and stenting was crucially dependent on the development of effective antithrombotic therapy following intervention. Indeed, the intensity and duration of dual antiplatelet therapy has been the subject of considerable controversy and of a large number of randomised clinical trials over the last decade in particular. An ESC Focused Update on Dual Antiplatelet Therapy will be presented for the first time by Marco Valgimigli at the ESC meeting in Barcelona. In a timely review in EuroIntervention, he and his colleagues provide an overview of trials on dual antiplatelet therapy, incorporating an updated meta-analysis in a document which may serve as a useful companion to the guidelines document19.

Bioresorable scaffolds is another area which has attracted considerable debate and many studies in recent years20. Yuki Katagiri, Gregg Stone and Yoshi Onuma provide an overview of the inception and current status of these devices as well as a perspective on future developments21. In spite of the considerable progress in catheter-based treatment of coronary stenosis, future events continue to be determined to a large extent by disease progression in non-intervened segments22. Javaid Iqbal, Robert Widmer and Bernie Gersch provide a review of medical therapy and highlight the importance of optimal therapy in revascularised patients23. In the final paper, as we look to the future, Werner Mohl et al provide an interesting overview of developments in cell therapy and its potential for translation to endogenous repair24.

Of course, progress in percutaneous coronary intervention has also spawned innovation in the transcatheter treatment of valvular heart disease. With this in mind, a second dedicated issue of EuroIntervention will be published to coincide with PCR London Valves in late September, highlighting progress and the state of the art in the field of structural interventions. We hope that you will find both series of papers a valuable resource and a fitting way to commemorate 40 years of percutaneous cardiac intervention.

Supplementary data

Moving image 1. Andreas Grüntzig explaining the bimanual technique. It is particularly helpful even today when it is necessary to intubate the coronary artery deeply with the guiding catheter to pass a tight lesion with the balloon. The voice in the background is that of Spencer King. The case was performed in Atlanta, GA, USA, in 1983.

Moving image 2. Interview with the first PTCA patient, Mr Bachmann. A video from the DVD “PTCA: a history”. Reproduced with permission from angioplasty.org. The full interview is available at the following link: http://www.ptca.org/voice/2012/09/16/35th

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.

Andreas Grüntzig explaining the bimanual technique. It is particularly helpful even today when it is necessary to intubate the coronary artery deeply with the guiding catheter to pass a tight lesion with the balloon. The voice in the background is that of Spencer King. The case was performed in Atlanta, GA, USA, in 1983.

Interview with the first PTCA patient, Mr Bachmann. A video from the DVD “PTCA: a history”. Reproduced with permission from angioplasty.org. The full interview is availabe at the following link: http://www.ptca.org/voice/2012/09/16/35th