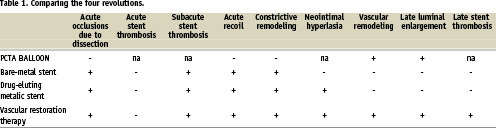

The invention of balloon angioplasty as a treatment of obstructive coronary disease by Andreas Grüntzig in 1977 was a huge leap forward in technology, and undoubtedly will always remain the first revolution in interventional cardiology. However, this technique was plagued by multiple problems including the risk of acute occlusion of the vessel due to extensive dissection requiring emergency bypass surgery1. While late luminal enlargement and vascular remodelling could occur, more often constrictive vascular remodelling was the case instead, with consequent restenosis. The advent of bare metal stenting and the landmark BENESTENT trial have established bare metal stenting as the second revolution in interventional cardiology2. This technology provided a solution to acute vessel occlusion by sealing the dissection flaps and preventing recoil. The rate of subacute occlusion was reduced to 1.5%, making emergency by-pass surgery a rare occurrence, truly a thing of the past. Restenosis rates were further reduced from 32% to 22% at seven months, but this was still high, and neointimal hyperplasia still occurred, necessitating repeat revascularisation. Since the vessel was now caged with metal, late luminal enlargement and advantageous vascular remodelling no longer occurred. Another problem, namely that of late stent thrombosis, was also first described3. To solve the issue of in-stent restenosis - after the failure of brachytherapy - drug eluting stents were introduced. Indeed, the follow-up of the first 45 patients implanted with the sirolimus eluting Bx velocity stent (Cordis, Johnson & Johnson, Warren, NJ, USA) had negligible neointimal hyperplasia. This was confirmed in the RAVEL study4,5. Drug eluting stents were thus dubbed the third revolution in interventional cardiology. Both large scale randomised trials and all-comer registries showed excellent results in terms of the need for repeat revascularisation. This technology brought closer the results of percutaneous coronary intervention to that of coronary bypass graft surgery. Serruys’ “rosy” prophecy came true6, however, it soon turned out that, as in all true “roses”, this one also has its thorns. The thorn of the first generation of drug eluting stents was an increased risk of late stent thrombosis. Registries of all comers treated with drug eluting stents showed late stent thrombosis rates of 0.53% per year, with a continued increase to 3% over four years7,8. In patients with complex multivessel disease (ARTS II), the rate of combined definite, probable and possible stent thrombosis was as high as 9.4% at five years, accounting for 32% of MACE events9. In addition, the pathology showed uncovered struts and inflammatory reaction in post-mortem specimens. Vasomotion testing showed abnormal vasoconstriction response to acetylcholine distal to the stent, suggesting that the structure and function of the endothelium remained abnormal10. All these problems promise to be solved with the advent of fully biodegradable scaffolds such as the BVS stent (Abbott Laboratories. Abbott Park, Il, USA) tested in the ABSORB trial11. This new technology, heralded as the fourth revolution in interventional cardiology, offers the possibility of transient scaffolding of the vessel to prevent acute closure and recoil. The scaffold will remain in place, eluting an antiproliferative drug that will counteract constrictive remodelling and excessive neointimal hyperplasia. However, ultimately after a period of two years, the stent struts are reabsorbed, proteoglycan is deposited. Within three to four years there is complete integration of the device into the vessel wall with infiltration by functional smooth muscle cells; with 100% of the struts tissue-covered and 100% apposed, as shown by optical coherence tomography in the pilot ABSORB cohort A12. In addition, it appears that the lumen enlarges and the vessel positively remodels. Vasomotion testing demonstrates restored normal vasodilatory response to acetylcholine and nitroglycerine of the endothelium within the previously scaffolded area of the vessel suggesting that the normal endothelial structure and function are fully restored. Thus, the new era in interventional cardiology is the era of Vascular Restoration Therapy or VRT, with fully biodegradable devices. The new “rosy” prophecy is that this technology will provide the ultimate solution to the problem of late stent thrombosis, and that this rose won’t have any thorns! (Table 1).