Abstract

Aims: We aimed to determine whether shortening the duration of P2Y12 inhibitor therapy can reduce the risk of bleeding without increasing the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events following coronary stenting in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF).

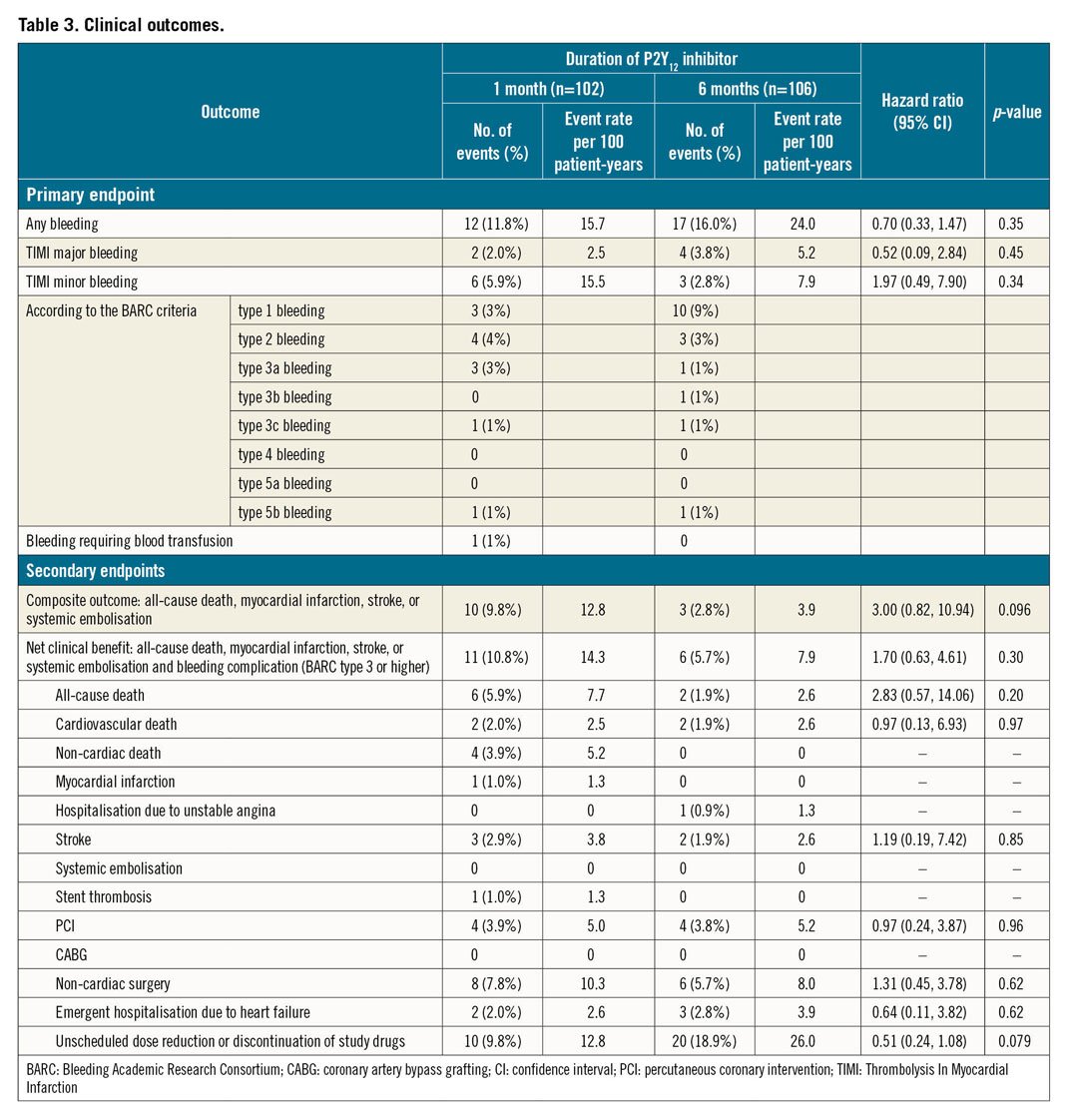

Methods and results: The SAFE-A is a randomised controlled trial that compared one-month and six-month P2Y12 inhibitor therapy, in combination with aspirin and apixaban for patients with AF who require coronary stenting. The primary endpoint was the incidence of any bleeding events, defined as Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction major/minor bleeding, bleeding with various Bleeding Academic Research Consortium grades, or bleeding requiring blood transfusion within 12 months after stenting. The study aimed to enrol 600 patients but enrolment was slow. Enrolment was terminated prematurely after enrolling 210 patients (72.7±8.2 years; 81% male). The incidence of the primary endpoint did not differ between the one-month and six-month groups (11.8% vs 16.0%; hazard ratio [HR] 0.70, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.33-1.47; p=0.35).

Conclusions: The study evaluated the safety of withdrawing the P2Y12 inhibitor from triple antithrombotic prescription one month after coronary stenting. However, enrolment was prematurely terminated because it was slow. Therefore, statistical power was not sufficient to assess the differences in the primary endpoint.

Introduction

Approximately 5% to 10% of patients who require coronary stent implantation have an indication for long-term oral anticoagulation to prevent adverse events related to atrial fibrillation (AF)1,2. Such patients require triple antithrombotic therapy with aspirin, a P2Y12 inhibitor, and an anticoagulant to prevent both stroke and stent thrombosis. However, compared to dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), triple antithrombotic therapy is associated with a twofold to threefold increased risk of bleeding complications3,4. Therefore, it is of key importance to clarify the risk-benefit profile of triple antithrombotic therapy in such patients.

The WOEST study reported that dual therapy with warfarin and a P2Y12 inhibitor was superior to triple therapy with warfarin, a P2Y12 inhibitor, and aspirin in terms of the risk of bleeding complications, without compromising protection against major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) after coronary stent implantation5. To date, several randomised controlled trials, including PIONEER AF-PCI, RE-DUAL PCI, and AUGUSTUS, have demonstrated that non-vitamin K oral anticoagulant (NOAC)-based strategies are superior to warfarin-based triple therapy regarding bleeding event rates6,7,8. For patients with AF who require coronary stenting, the current guidelines recommend that triple therapy with an anticoagulant plus two antiplatelet agents should be administered for one or six months, depending on the individual patient’s risk for ischaemia and bleeding9. However, the optimal strategy for triple therapy in this patient population remains challenging.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of short-duration (one-month) P2Y12 inhibitor therapy, in combination with aspirin and apixaban, for patients with AF who require percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with drug-eluting stent implantation.

Methods

STUDY DESIGN

The SAFE-A study was a multicentre, prospective, randomised, open-label, clinical trial that compared one-month and six-month P2Y12 inhibitor therapy in combination with aspirin and apixaban for patients with AF who require PCI with drug-eluting stent implantation. The major inclusion criteria were non-valvular AF, coronary artery disease indicated for PCI using drug-eluting stents, CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥1, and an age of 20 years or older. The major exclusion criteria were stenting of the left main trunk, bifurcation lesion treated with the two-stent technique, advanced chronic kidney disease (creatinine clearance <15 mL/min), and indications for surgery or pulmonary vein isolation. Patients who received any types of second-generation or third-generation drug-eluting stents were included. The design and rationale of the SAFE-A trial, including the full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria, have been reported elsewhere10. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics review board of each participating institute, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was registered in the UMIN Clinical Trial Registry (UMIN000015923).

RANDOMISATION AND TREATMENT

Within 72 hours after PCI, eligible patients were randomised in a 1:1 ratio to receive a P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel or prasugrel) for either one month or six months, in combination with both aspirin and apixaban (triple therapy). Randomisation was conducted using an electronic system, stratifying patients by age (≥65 years or <65 years), presence of acute coronary syndrome, and HAS-BLED score (≥3 or <3). Patients received apixaban 5 mg twice daily, which could be reduced to 2.5 mg twice daily if the patient was 80 years or older, had body weight ≤60 kg, or had serum creatinine levels ≥1.5 mg/dL. Either clopidogrel (75 mg/day) or prasugrel (3.75 mg/day) was used as the P2Y12 inhibitor at the discretion of the treating physician at the time of enrolment.

ENDPOINTS AND FOLLOW-UP

Patients were evaluated at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after randomisation to obtain information regarding the occurrence of endpoints, incidence of adverse events, and compliance with the study medication. The primary endpoint of this study was the incidence of any bleeding events within 12 months after PCI, which was defined as Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) major and minor bleeding (Supplementary Table 1), bleeding with various Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) grades (Supplementary Table 2), or bleeding requiring blood transfusion. Major secondary endpoints included the composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke, or systemic embolisation, as well as the net clinical benefit (all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke, systemic embolisation, or bleeding with BARC type 3 or higher). Other secondary endpoints included the individual components of the composite endpoints, as described in detail elsewhere10. Clinical follow-up was performed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after randomisation in a similar manner as an outpatient visit; if this was not possible, then a telephone interview or survey with a letter was permitted. Because this study had an open-label design, the clinical endpoints were assessed and classified by the Endpoint Assessment Committee whose members were blinded to the assigned treatment at the time of the outcome evaluation.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

This study was designed to evaluate and compare the safety of one-month and six-month P2Y12 inhibitor treatment in combination with aspirin and apixaban in AF patients who require drug-eluting stent implantation. Our hypothesis was that the incidence of bleeding events in this population would be lower with shorter (one-month) P2Y12 inhibitor treatment.

In the APPRAISE-2 trial which evaluated the efficacy of apixaban when added to DAPT in patients with acute coronary syndrome, the incidence of any bleeding events was 18.5% in the apixaban group and 8.4% in the placebo group11. Assuming an incidence of the primary endpoint of 15% for six-month P2Y12 inhibitor treatment, a sample size of 550 patients was calculated to be necessary to detect a risk reduction of 50% associated with withdrawing the P2Y12 inhibitor from triple therapy at one month, with 80% power and an α level of 0.05. Accounting for loss to follow-up, the target sample size for this study was established as 600 patients (300 patients per group). However, because of slow enrolment, further enrolment was stopped after 210 patients had been enrolled. The study was continued until all enrolled patients had been followed up for a minimum of six months.

Continuous variables are presented as means with standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges, as appropriate. The unpaired t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the two groups. Categorical variables are reported as absolute values and percentages and were compared using Fisher’s exact test.

Clinical outcomes were analysed based on an intention-to-treat principle. No multiplicity adjustment was made for the comparison of primary and secondary endpoints. The primary endpoint was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between groups were evaluated using the log-rank test. The hazard ratio (HR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) for group comparisons were estimated using a Cox proportional hazards model that included the treatment regimen as a covariate stratified according to age, presence of acute coronary syndrome, and HAS-BLED score. Pre-specified subgroup analyses of the primary endpoint were performed.

In all analyses, p<0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed by biostatisticians (M. Gosho and T. Ohigashi) using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

STUDY POPULATION

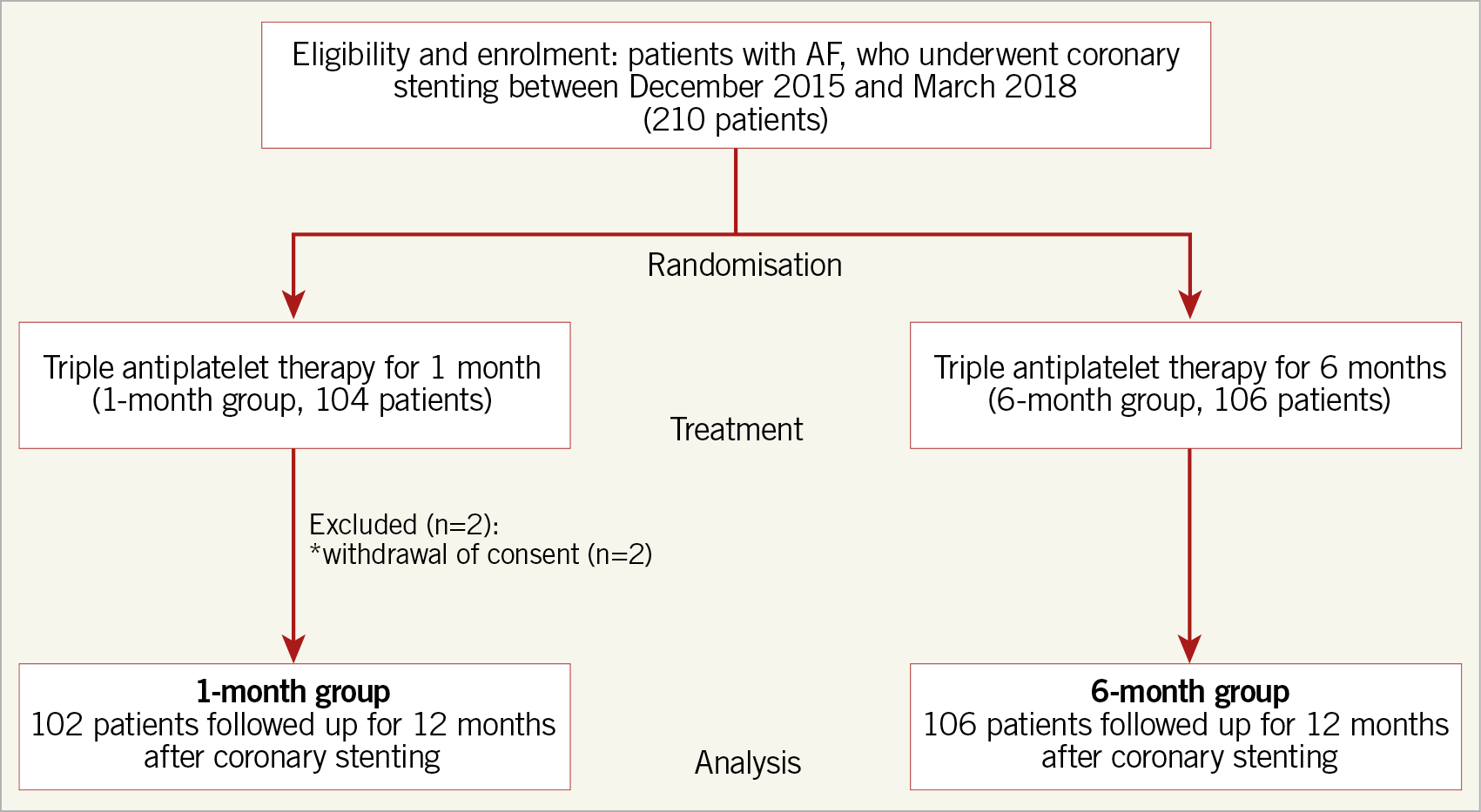

Between December 2015 and March 2018, a total of 210 eligible patients from 66 participating centres in Japan were enrolled. After excluding two patients who withdrew consent, our analysis included 208 patients who completed the trial (one-month group, 102 patients; six-month group, 106 patients) (Figure 1). Although the study had originally aimed to enrol 600 patients (300 per group), enrolment was terminated after a sample size of 210 patients was reached because of slow enrolment.

Figure 1. Study flow chart. AF: atrial fibrillation

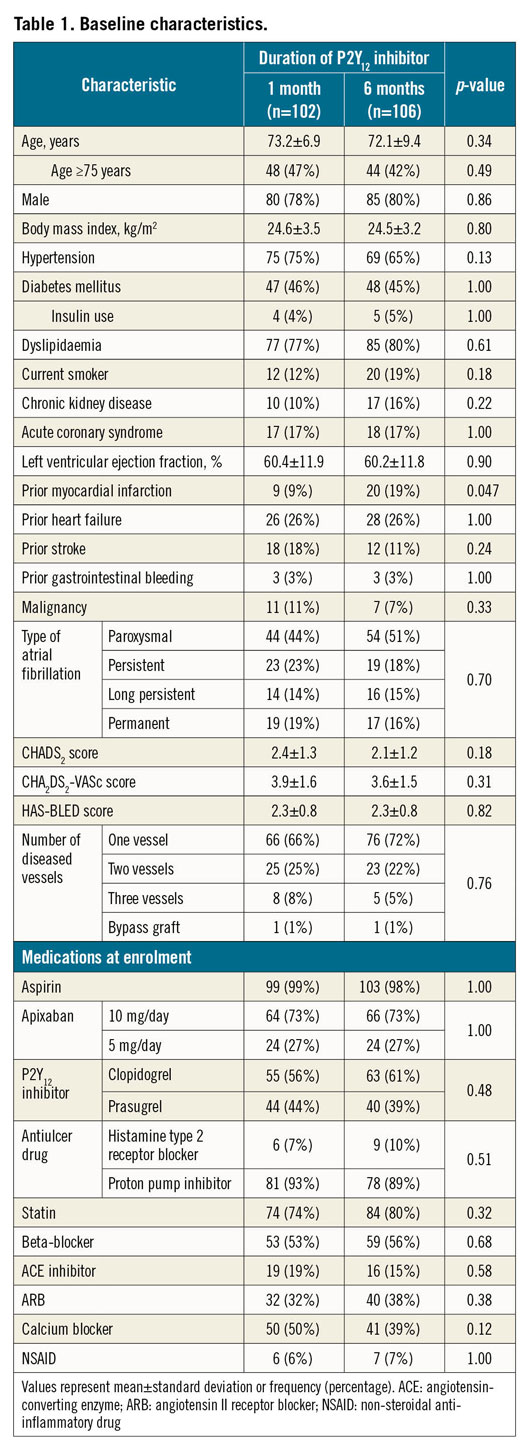

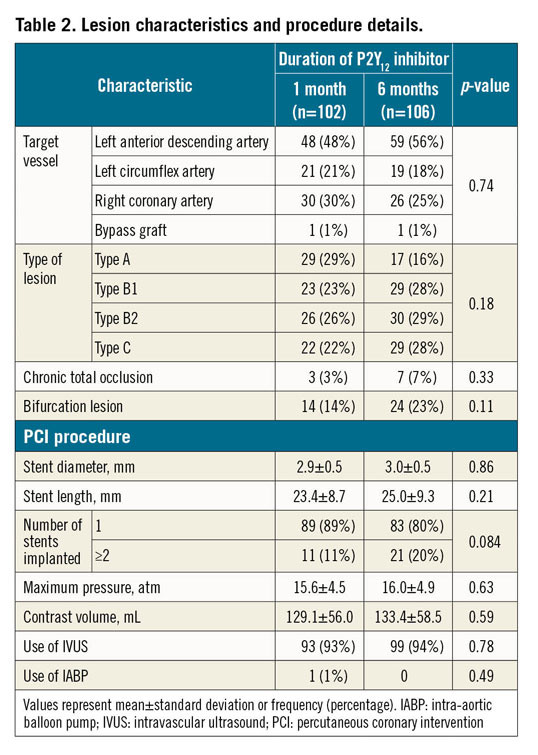

The baseline patient characteristics (Table 1) were well balanced between the two groups, except for the prevalence of prior myocardial infarction. There were no significant differences between groups regarding lesion characteristics or procedural details (Table 2). The prescribed antithrombotic drugs at enrolment and at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after randomisation are shown in Supplementary Figure 1. The study was continued until all enrolled patients had been followed up for a minimum of six months. The rates of completing 12 months of follow-up were 33% for the one-month group and 31% for the six-month group (p=0.77). The median and interquartile ranges of the follow-up period were 11.7 months (6.0, 12.2) and 10.0 months (5.7, 12.1), for the one-month group and six-month group, respectively (p=0.37).

CLINICAL OUTCOMES

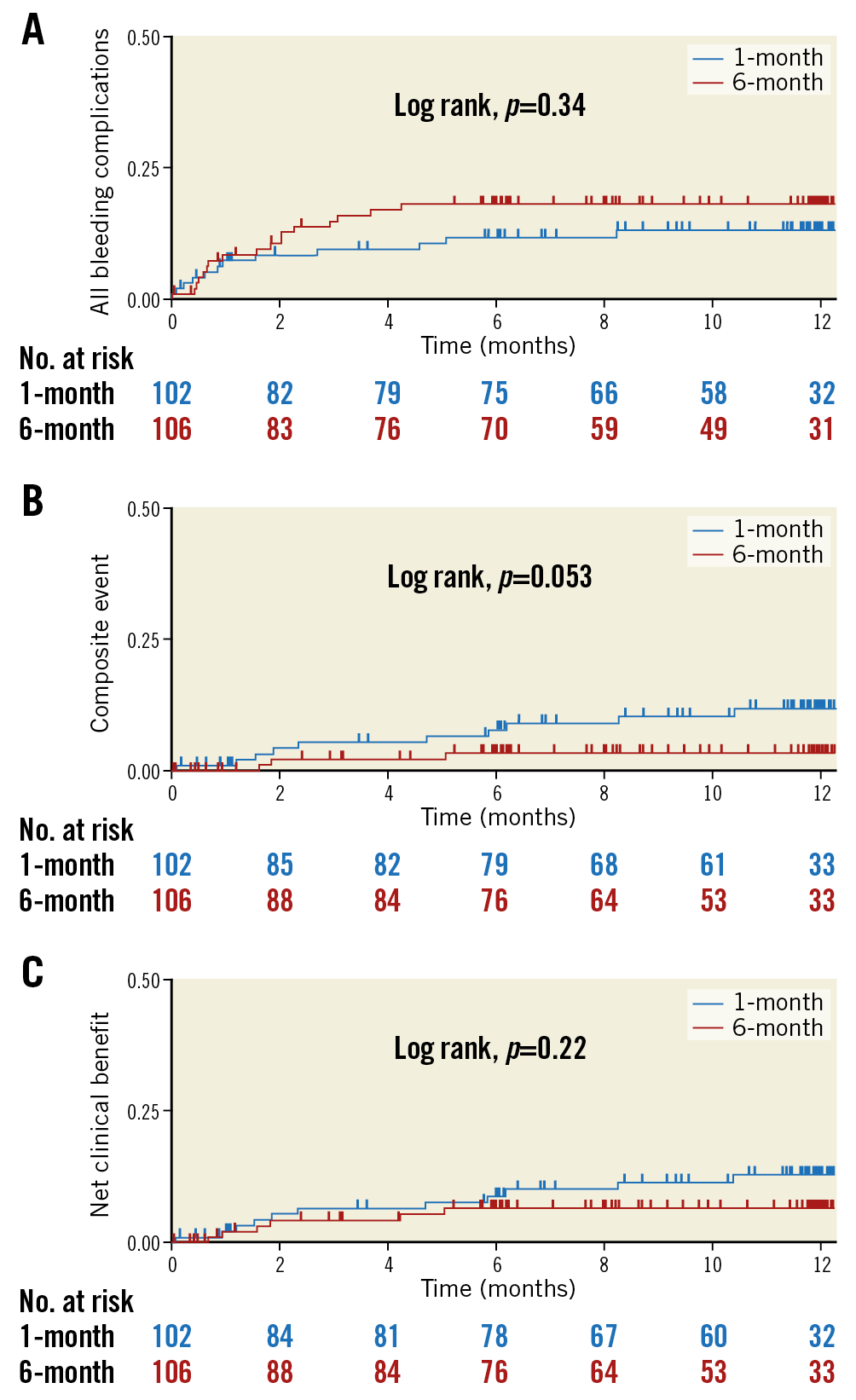

Within 12 months after PCI, the primary endpoint (any bleeding) occurred in 11.8% of patients in the one-month group and in 16.0% of patients in the six-month group (HR 0.70, 95% CI: 0.33-1.47; p=0.35) (Table 3, Figure 2A). The major secondary composite endpoint occurred in 9.8% of patients in the one-month group and 2.8% of patients in the six-month group (HR 3.00, 95% CI: 0.82-10.94; p=0.096), with the difference explained mainly in terms of the higher incidence of non-cardiac death for the one-month group (Table 3, Figure 2B). There was no significant difference in the net clinical benefit of the one-month and six-month groups (10.8% vs 5.7%; HR 1.70, 95% CI: 0.63-4.61; p=0.30) (Table 3, Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier curves. Cumulative incidence of the primary endpoint (any bleeding events; A), composite secondary endpoint (all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke, or systemic embolisation; B), and net clinical benefit (all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke, systemic embolisation, or BARC type 3 or higher bleeding; C) within 12 months after coronary stenting. BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium

Regarding the individual secondary endpoints, non-cardiac death was observed more frequently in the one-month group than in the six-month group (3.9% vs 0%; p=0.048); there were three cancer-related deaths and one pneumonia-related death. Stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction occurred in only one patient (in the one-month group) (Table 3).

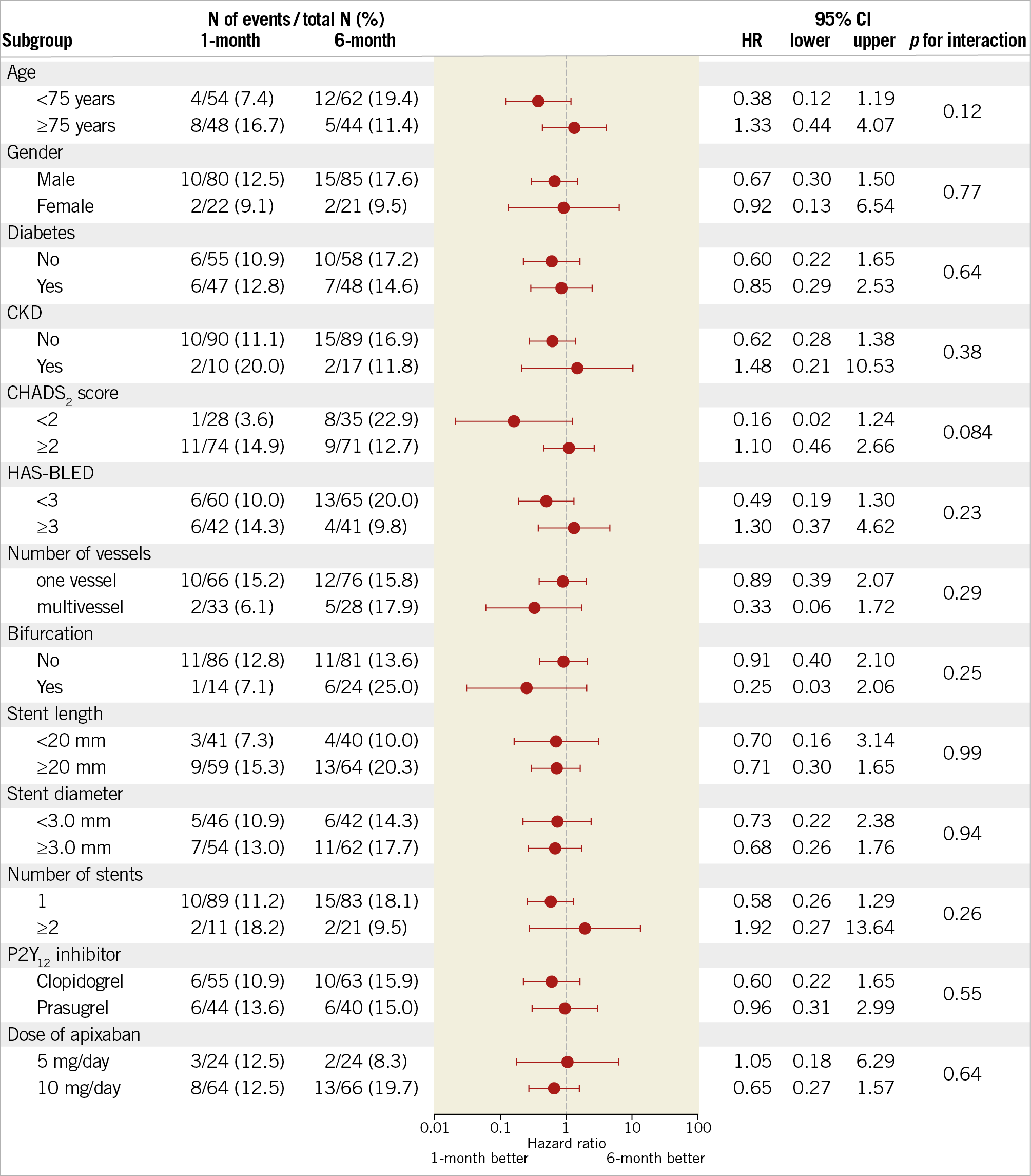

Finally, the pre-specified subgroup analysis revealed no significant interactions with the lack of treatment effect, which was consistent across all pre-specified subgroups (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Pre-specified subgroup analysis of the primary endpoint. Patients were stratified according to the duration of triple antithrombotic therapy (one-month group vs six-month group). Data are presented as the number of patients with events, crude incidence rates, and hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). Data for the six-month group were used as a reference. CKD: chronic kidney disease

Discussion

The SAFE-A study was the first randomised trial comparing one month and six months of P2Y12 inhibitor therapy, combined with aspirin and apixaban, for patients with AF who require coronary stenting. The major findings were that one-month P2Y12 inhibitor therapy was not superior to six-month P2Y12 inhibitor therapy as part of a triple antithrombotic therapy regimen to decrease the risk of bleeding events. Furthermore, no significant differences were found in the rates of ischaemic coronary events between one-month and six-month P2Y12 inhibitor therapy when combined with apixaban-based dual therapy.

In the present study, the incidence of the primary endpoint tended to be lower in the one-month group than in the six-month group (11.8% vs 16.0%; HR 0.70, 95% CI: 0.33-1.47; p=0.35).

The SAFE-A study failed to demonstrate the superiority of short-term (one-month) P2Y12 inhibitor therapy for reducing bleeding complications. The lack of statistical significance was probably due to the limited number of patients enrolled. Although the study had originally aimed to enrol 600 patients (300 per group), enrolment was terminated after a sample size of 210 patients was reached. Slow enrolment was probably related to the physicians’ concerns regarding the increased risk of bleeding associated with prolonged triple therapy.

The balance between the ischaemic risk and bleeding risk is particularly important for patients who require anticoagulation or antiplatelet treatment. Regarding patients without AF, shorter (three- to six-month) DAPT was associated with a significant reduction in major bleeding events, without increasing the risk of ischaemic events, compared with the standard 12 months of DAPT12. However, current evidence regarding the safety and effectiveness of triple therapy (combination of dual antiplatelet and anticoagulant treatments) for patients with AF remains limited. Recently, several randomised controlled trials combining NOAC and antiplatelet therapy have aimed to address such limitations and to compare rivaroxaban-, dabigatran-, and apixaban-based triple therapy strategies against warfarin-based triple therapy6,7,8. Recently, the AUGUSTUS trial found that the combination of apixaban and a P2Y12 inhibitor was associated with fewer bleeding events than a warfarin-based strategy (10.5% vs 14.7%; HR 0.69, 95% CI: 0.58-0.81) among patients with AF who presented with recent acute coronary syndrome, or who required PCI8. In both arms, the addition of aspirin compared to placebo was associated with an increased incidence of bleeding (16.1% vs 9.0%; HR 1.89, 95% CI: 1.59-2.24). The results of recent trials suggested that NOAC-based strategies should be preferred over warfarin-based strategies to reduce the risk of bleeding in patients with AF who require coronary stenting.

The SAFE-A study exhibited two main differences from previous studies. First, early withdrawal of the P2Y12 inhibitor from NOAC-based strategies represents a unique feature of this study design. Previous studies examined the safety and efficacy of the combination of NOAC and a P2Y12 inhibitor, and withdrawing aspirin, as compared to warfarin-based strategies. Second, in this study, approximately 40% of patients received prasugrel as the P2Y12 inhibitor, whereas most patients received clopidogrel as the P2Y12 inhibitor in previous studies. It is unclear whether clopidogrel or aspirin should be stopped early to reduce the risk of bleeding for patients receiving NOAC-based antithrombotic therapy. Withdrawing aspirin from DAPT after stent implantation raises concerns about the loss of protection against coronary ischaemic events. The effect and safety of very early withdrawal of aspirin therapy (at one to two weeks) remain topics of debate because the first weeks after PCI are known to represent the period with the highest risk for coronary ischaemic events. The AUGUSTUS trials did find a slightly smaller number of coronary ischaemic events among patients who used aspirin compared to those who did not (2.9% vs 3.6%; HR 0.81, 95% CI: 0.59-1.12), although event rates were low and the trial was not adequately powered to assess differences in individual ischaemic outcomes8. Recent meta-analysis showed a significant increase of stent thrombosis (risk ratio 1.59, 95% CI: 1.01-2.50; p=0.04) with a double therapy of NOAC and P2Y12 inhibitor without aspirin, as compared to triple therapy13. Another matter of concern is the polymorphism of cytochrome P450 2C19 (CYP2C19), which affects the pharmacokinetics of clopidogrel14. Poor CYP2C19 metabolism, which is associated with a lack of response to clopidogrel, is noted among approximately 20% of the Asian population15. Our present results suggest that it may be feasible to withdraw the P2Y12 inhibitor and continue aspirin and apixaban for patients with AF who require drug-eluting stent implantation. Nevertheless, the optimal antithrombotic treatment regimen for these patients remains to be clarified in further clinical studies with adequate power.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the number of enrolled patients was smaller than the target sample size established based on the original design because enrolment was slow and had to be terminated prematurely. Second, due to the open-label design, we could not exclude selection bias. However, the assessment of endpoints was blinded. Third, approximately 40% of patients included in this study were using prasugrel. The approved dose of prasugrel in Japan (20 mg and 3.75 mg/day for loading and maintenance, respectively) is lower than that approved in Western countries. Because the present study involved Japanese patients, the findings cannot be generalised to other ethnic populations. Fourth, unscheduled dose reduction or discontinuation of study drugs was performed for 9.8% and 18.9% of patients in the one-month group and six-month group, respectively, which might have affected the results of the study.

Conclusions

SAFE-A is the first randomised trial to compare one-month and six-month P2Y12 inhibitor therapy in combination with aspirin and apixaban for patients with AF who underwent PCI with drug-eluting stent implantation. The study was prematurely terminated because of slow enrolment and was not powered to assess the differences in the primary endpoint. We could not confirm that early stopping of the P2Y12 inhibitor can reduce bleeding events after PCI for patients with AF.

|

Impact on daily practice SAFE-A is the first randomised trial to compare one-month and six-month therapy with a P2Y12 inhibitor combined with aspirin and apixaban to prevent major adverse cardiovascular events for AF patients who require coronary stenting. The unique approach involved withdrawing the P2Y12 inhibitor at one month after stenting. However, the results failed to show the superiority of such short-term P2Y12 inhibitor treatment for reducing bleeding events, probably because of the inadequate statistical power. |

Acknowledgements

We thank Hiroyuki Hosokawa, Masahiro Sakai, Eriko Onose, and Koichi Hashimoto from the Tsukuba Clinical Research & Development Organization, University of Tsukuba, for their invaluable assistance with this study. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding

This study was sponsored by grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb K.K.

Conflict of interest statement

K. Aonuma has received research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb K.K., and belongs to departments endowed by commercial entities Boston Scientific Corporation, Japan Lifeline Co., Ltd., Nihon Kohden Corporation, BIOTRONIK Japan, Inc., Toray Industries, Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH, and Century Medical, Inc. During the study, M. Gosho received lecture and/or consultant fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, and Asahikasei Pharma. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.