Introduction

This is the second article in the EuroIntervention Tools & Techniques series and deals with the radial approach for percutaneous coronary intervention. The following is an overview of its management and highlights the salient technical features to be covered in the online version. The complete, unabridged chapter with dynamic angiographic images can be viewed at www.eurointervention.org

Background

Cardiac catheterisation has traditionally been performed via the transfemoral approach (TFA). Campeau et al first described the radial approach to coronary angiography in 19891; later, Kiemeneij et al published the first series of ballon angioplasty2 and bare-metal stent3 implantation performed by radial approach. Since then, the transradial approach (TRA) percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), has become increasingly common. TRA has been shown to be safer and more cost-effective than the classic femoral approach, with similar efficacy rates for a broad spectrum of patients with fewer access site or bleeding complications4-8.

The radial artery is relatively superficial, allowing easy identification and puncture of the artery. It is also easily compressible and there are no important nerves running along side it, making the puncture and compression relatively safe. A meta-analysis published in 2009 showed a significant reduction in bleeding complications9.

Studies also show that the TRA can significantly reduce hospital stay and costs after diagnostic procedures or PCI, and is generally preferred by patients as they can mobilise immediately after the procedure10.

Although a larger number of procedure failures are reported when compared with femoral approach6,9, the success rate for TRA is more than 95%.

Indications

TRA should be considered as the preferred access site in the presence of aorto-iliac disease. However, it is only used by default by some operators. Provided operator expertise is adequate, we don’t see any inconvenience in performing PCI by TRA in all comers. Since TRA is associated with lower major bleeding and with a tendency to reduce adverse events9, TRA should be the preferable approach if the bleeding risk is higher or the achievement of correct haemostasis by femoral approach is difficult, for example with extreme obesity7.

Difficulties

There are some drawbacks that one must be aware of before embarking on the TRA:

– The learning curve for TRA is steeper than for TFA15-17

– Crossover from TRA to TFA is significantly higher than in the opposite way9. Difficult anatomy may enable operator to continue by radial (Figures 1 and 2).

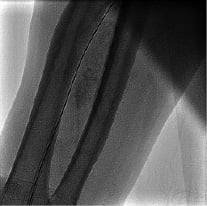

Figures 1 and 2. Two cases of extreme aortic tortuosity. A transfemoral approach may be advised in this scenario.

– Small artery size restricts interventional device options;

– The risk of transient or permanent radial artery occlusion with a normal Allen´s test is 5.3% and 2.8% respectively12, and medication is required to avoid vasospasm13 and thrombosis14.

– Difficult or tortuous anatomy can lead to longer procedures with higher radiation exposure compared to similar femoral access procedures11.

Methods

This issue reviews the advantages and disadvantages of TRA, and the most common techniques to work by TRA. First, we describe the preparation set-up, then we describe the puncture, catheter engaging techniques, and haemostasis. Some examples are shown with problems to advance catheter and suggestions to overcome it. Finally some tips and tricks (Figures 3-5) are presented in the difficult situations section.

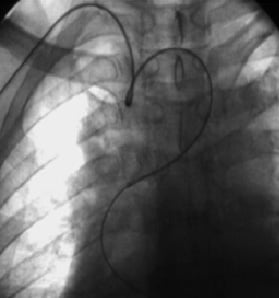

Figures 3-5. Perforation of the radial artery with the guidewire from the introducer in a tortuous artery (Figure 3). A hydrophilic wire is advanced through the lumen under fluoroscopy (Figure 4). A diagnostic catheter is advanced over the wire and easily crosses the zone of spasm and perforation. After the PCI was completed, withdrawal of the introducer to the distal artery and contrast injection shows that the artery perforation has sealed and there is no further contrast extravasation (Figure 5).