Today we are going to offer our readers a homemade and natural remedy for headaches. First, prepare a water bath at 80°C and a spray bottle with distilled water at 0°C. In a 100 mL dry flask, pour 2 g of salicylic acid, 6 mL of acetic anhydride and five drops of 85% phosphoric acid. Immerse the flask for a few seconds in the hot water bath and stir gently to dissolve the salicylic acid. Now instal a bubble condenser and heat in a water bath at 70-80°C for 15 minutes. Done? Then there are five or six additional steps that I do not remember: end of the recipe (but nice tutorials are available on YouTube). Clearly, this was not the pilot script for a new TV series in the wake of “Breaking Bad”, but just an introduction to the art and magic of synthesising aspirin, also known as acetylsalicylic acid. I could refer you to more appropriate references if you are interested in the remarkable story of this sensational drug from its origins in ancient Egypt to today’s worldwide recognition as a blockbuster. The list of indications for this derivative of the willow tree is gigantic, from the relief of pain and fever to the treatment of inflammation for a variety of clinical conditions.

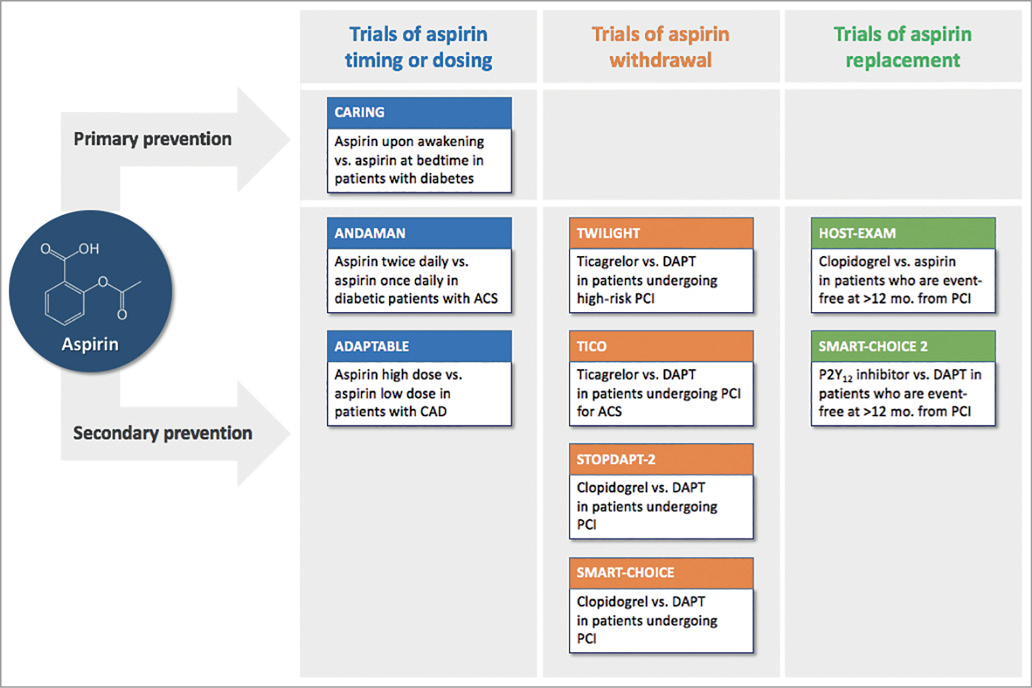

Obviously, based on its antiplatelet effects, low-dose aspirin is also useful for a number of indications in cardiovascular disease prevention. As 2018 gives way to 2019, it is worth recapitulating on the milestones of a very difficult year in the history of aspirin for cardiovascular medicine. In the secular chronicles that mark aspirin’s history, there have certainly been many more difficult years than this, yet aspirin has always remained up there on its pedestal, a cornerstone in the cardiologist’s armamentarium. To paraphrase someone much more authoritative, two things are endless: the universe and the cardiologist’s love for aspirin… but I’m not so sure of the former. Recently, at least four large randomised trials have challenged the aspirin dogma, while others are ongoing (Figure 1). Let’s see where we are, and why.

Figure 1. Ongoing studies of aspirin in the field of cardiovascular disease. ACS: acute coronary syndromes; CAD: coronary artery disease; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

Aspirin for primary prevention

The use of aspirin as a primary prevention strategy is a divisive choice. Some think it is useless, others think that the day a heart attack occurs, the doctor will regret never prescribing it. If we look at data from before 2018, doubts are unsurprising. In a meta-analysis of 118,445 individuals from 11 trials of primary prevention, aspirin reduced non-fatal myocardial infarction by 22% but death by only 6%. This came at the price of a 59% relative increase in gastrointestinal bleeding and a 33% relative increase in haemorrhagic stroke1,2. As such, the problem is not aspirin per se, but the level of cardiovascular risk that allows physicians to ignore the risk of bleeding as compared to the beneficial reduction in myocardial infarction. For subjects at low cardiovascular risk, the game is probably not worth the candle. This is certainly reflected in current European guidelines for cardiovascular prevention, which assign a class III recommendation to aspirin for primary prevention3.

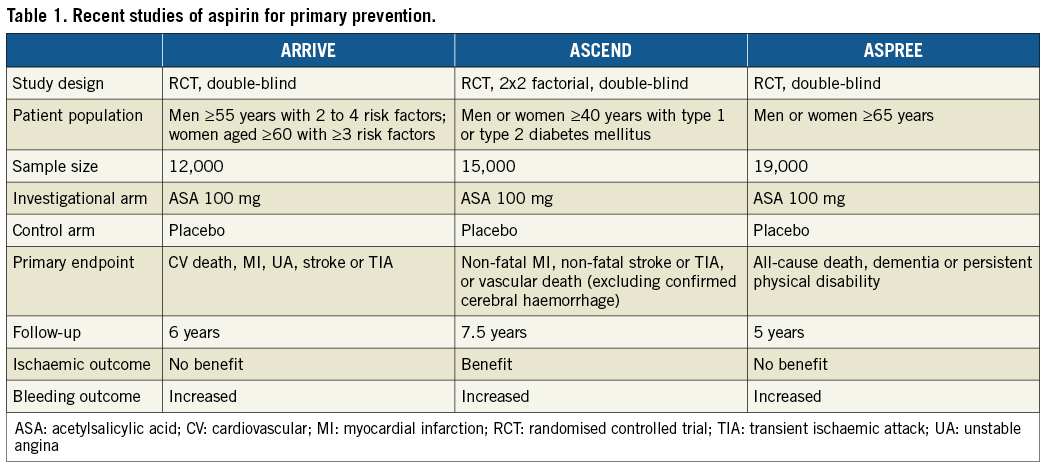

Earlier this year, over a period of a couple of months, three randomised trials have probably settled the debate. A common characteristic of these studies is that they intentionally included patients with “non-low” cardiovascular risk (Table 1)4. In the ARRIVE trial (N=12,546), this was actually not the case: the investigators targeted patients at moderate cardiovascular risk based on available risk calculators, but they finally ended up with a population at low risk5,6. At a median follow-up of five years, aspirin did not reduce ischaemic events (hazard ratio [HR] 0.96, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.81-1.13) compared with placebo, and increased gastrointestinal bleeding by 111%. The second trial, ASCEND (N=15,480), included only patients with diabetes. This time, aspirin reduced serious vascular events at a mean of 7.4 years by 12% (rate ratio 0.88, 95% CI: 0.79-0.97; p=0.01), but this small reduction was counterbalanced by a 29% relative increase in major bleeding7. The third trial, ASPREE (N=19,114), conducted in older (≥65 years) subjects, is quite peculiar in that it did not deserve just one publication in the New England Journal of Medicine, but rather three simultaneously8-10. At a median of 4.7 years, aspirin did not reduce the rate of cardiovascular disease (HR 0.95, 95% CI: 0.83-1.08) and increased the rate of major bleeding by 38%.

The overall picture delineated by these three studies is rather categorical and points clearly against the use of aspirin in the context of primary prevention. In the updated meta-analysis of 14 primary prevention trials of aspirin by Paul Ridker, including ARRIVE, ASCEND and ASPREE, the hazard ratio for mortality is now 0.97 (95% CI: 0.93-1.01)11. The multifaceted therapeutic properties of low-dose aspirin have been advocated as a means for such pleiotropic consequences as platelet inhibition and inflammatory effects, including cancer reduction and prevention of cognitive disorders12. However, not even these hypotheses have been confirmed so far by the long-term follow-up of ASCEND and ASPREE9,13.

Aspirin for secondary prevention

In the context of secondary cardiovascular prevention, many antithrombotic drugs have succeeded with mixed fortunes and a common denominator: being tested on top of aspirin. Dual antiplatelet therapy is the standard of care after an acute coronary syndrome and after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)14. Aspirin is also indicated for chronic therapy in patients with stable atherosclerosis, and even the new kid on the block in this setting - rivaroxaban, as tested in the COMPASS trial - is indicated on top of aspirin15. Yet, the rationale for aspirin-free approaches has slowly emerged, based on lessons from trials of anticoagulated patients such as WOEST, PIONEER-AF and RE-DUAL16. Indeed, aspirin established its success as a secondary prevention strategy in the era when other contemporary and broadly accepted medications were scarcely used (e.g., statins) or not available (e.g., ticagrelor or prasugrel). The line-up of clinical investigations exploring the effect of aspirin withdrawal on cardiovascular outcomes now faces the results of the first study of this kind conducted in the field of PCI, the large GLOBAL LEADERS trial.

The study hypothesis of GLOBAL LEADERS was that ticagrelor in combination with aspirin for one month and followed by ticagrelor monotherapy decreases the rate of all-cause mortality or new Q-wave myocardial infarction at 24 months compared with standard antiplatelet therapy (e.g., dual antiplatelet therapy for 12 months, followed by aspirin monotherapy)17. The trial fell short of its primary objective (p=0.07), but the interpretation is more problematic than it seems, because GLOBAL LEADERS entailed not just one comparison of antithrombotic strategies, but three. In the first month, all patients in the two arms were on dual antiplatelet therapy (e.g., with aspirin plus ticagrelor in the experimental group and with aspirin plus ticagrelor or clopidogrel in the reference group). Scrutiny of the event curves does not identify a significant separation during this timeframe. Between one and 12 months, the experimental strategy was ticagrelor monotherapy, which was compared with dual antiplatelet therapy. In this landmark period, ticagrelor monotherapy did better than its comparator. In fact, the p-value for death or myocardial infarction at 12 months was significantly in favour of the experimental strategy (p=0.028). The third portion of the trial (between 12 and 24 months) was a comparison of ticagrelor and aspirin monotherapies, where no difference was noted. Therefore, the strategy of ticagrelor monotherapy with aspirin withdrawal actually showed promise in GLOBAL LEADERS when compared with dual antiplatelet therapy, while the effect was neutral in the comparison of ticagrelor versus aspirin alone. The aspirin-free strategy is currently being investigated in other clinical trials, including the TWILIGHT study that has recently completed its enrolment16.

Conclusions

Does an aspirin a day keep the doctor away? Not really, at least for patients with no overt cardiovascular disease. A recent meta-analysis suggests that a one-dose-fits-all approach to the use of aspirin yields only modest benefits in cardiovascular prevention, possibly due to underdosing in patients of large body size and excess dosing in patients of small body size18. This hypothesis theoretically leaves an open door for new aspirin trials of primary prevention. Conversely, in patients with established coronary artery disease, a number of studies are trying to break down the monolithic conviction that aspirin must necessarily be part of any antithrombotic cocktail. With many ongoing investigations of dosing, timing, withdrawal and replacement (Figure 1), aspirin – whatever you think of it – will continue its millennial journey and remain in the spotlight for the years to come.