Abstract

Background: Clinical implications of the proximal optimisation technique (POT) for bifurcation lesions have not been investigated in a randomised controlled trial.

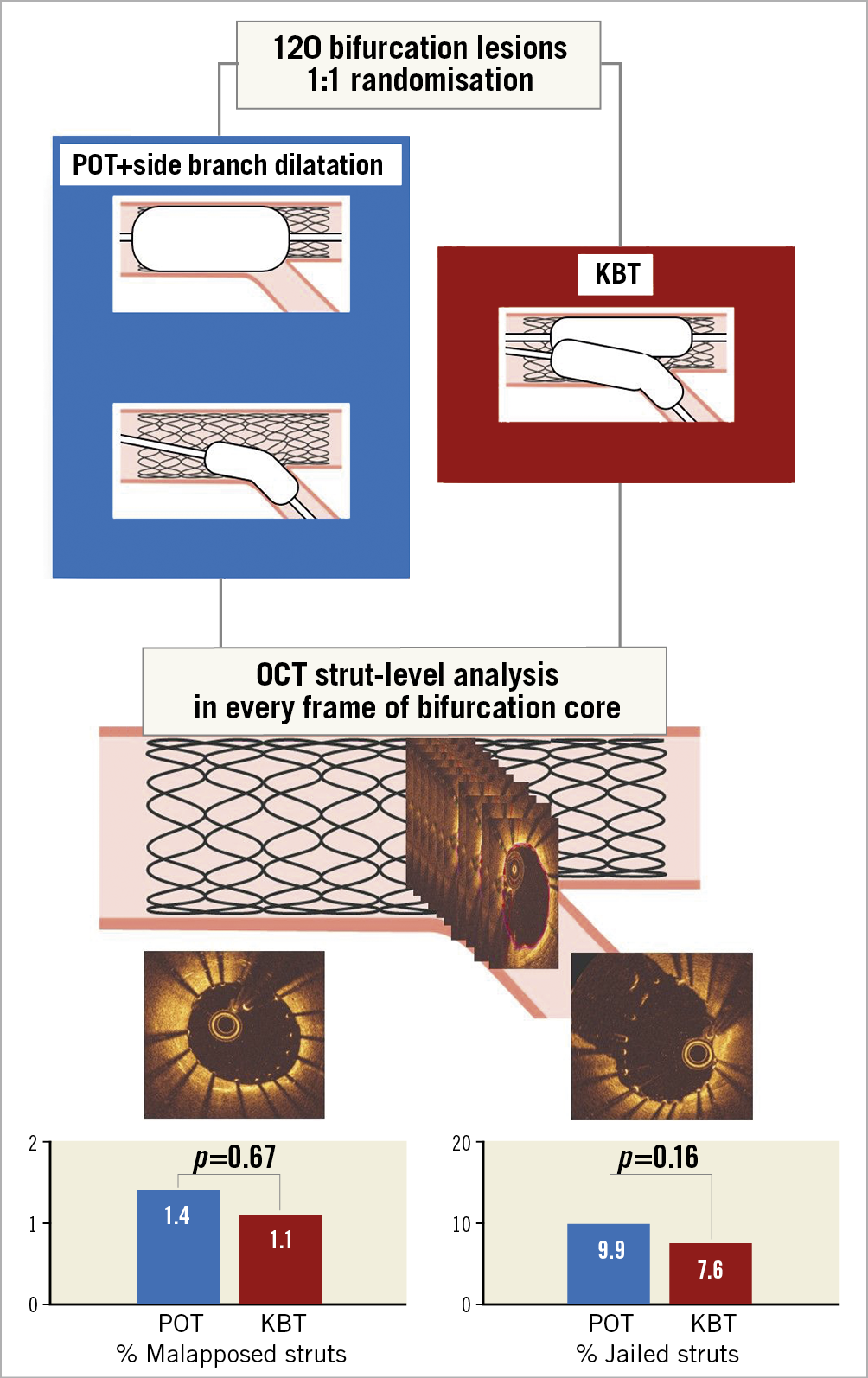

Aims: This study aimed to investigate whether POT is superior in terms of stent apposition compared with the conventional kissing balloon technique (KBT) in real-life bifurcation lesions using optical coherence tomography (OCT).

Methods: A total of 120 patients from 15 centres were randomised into two groups - POT followed by side branch dilation or KBT. Finally, 57 and 58 patients in the POT and KBT groups, respectively, were analysed. OCT was performed at baseline, immediately after wire recrossing to the side branch, and at the final procedure.

Results: The primary endpoint was the rate of malapposed struts assessed by the final OCT. The rate of malapposed struts did not differ between the POT and KBT groups (in-stent proximal site: 10.4% vs 7.7%, p=0.33; bifurcation core: 1.4% vs 1.1%, p=0.67; core’s distal edge: 6.2% vs 5.3%, p=0.59). More additional treatments were required among the POT group (40.4% vs 6.9%, p<0.01). At one-year follow-up, only one patient in each group underwent target lesion revascularisation (2.0% vs 1.9%).

Conclusions: POT followed by side branch dilation did not show any advantages over conventional KBT in terms of stent apposition; however, excellent midterm clinical outcomes were observed in both strategies.

Introduction

Coronary bifurcation lesions are involved in 15-20% of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) and represent a highly challenging lesion subset in interventional cardiology1. Provisional stenting is generally accepted as the first-line treatment for coronary bifurcation lesions. The kissing balloon technique (KBT) after crossover main vessel (MV) stenting is considered effective in securing side branch (SB) patency and removing jailed struts. Nonetheless, KBT efficacy has recently been questioned. KBT may lead to asymmetric proximal MV stent deformation or overexpansion, resulting in dissection due to inflation of two aligned balloons2,3,4.

The European Bifurcation Club recommends MV stenting with the proximal optimisation technique (POT) and provisional SB stenting as the primary approach for coronary bifurcation lesions1. POT involves balloon dilation at the proximal stent segment for apposition to the vessel wall before exchanging the SB wire. This enables easier SB wire access and reduces stent strut distortion and malapposition5,6. POT has been confirmed in bench testing; however, clinical evidence is still lacking7,8. Hence, this prospective open-label randomised study aimed to investigate whether POT is superior in stent apposition compared with conventional KBT in real-life bifurcation lesions by strut-level analyses with optical coherence tomography (OCT).

Methods

STUDY POPULATION AND DESIGN

This was a prospective, open-label, randomised study designed to compare POT with KBT after zotarolimus-eluting stent implantation (either Resolute Integrity® or Resolute Onyx™; Medtronic Vascular, Santa Rosa, CA, USA). Patients who underwent bifurcation PCI eligible for a provisional SB stenting strategy using a zotarolimus-eluting stent were enrolled, randomised into groups (POT followed by SB dilation [SBD] or KBT) using a web-based allocation system, and followed up for one year.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) SB bifurcation lesions ≥2.0 mm in diameter; (2) main branch stenosis within 5 mm from the SB ostium; (3) lesions treatable by a provisional SB stenting strategy in accordance with the European Bifurcation Club consensus; (4) lesion length ≤38 mm without other stenosis in the same vessel; (5) reference vessel diameter ≥2.5 mm; and (6) proximal bifurcation lesions among multiple bifurcations. Exclusion criteria are shown in the study protocol (Supplementary Appendix 1).

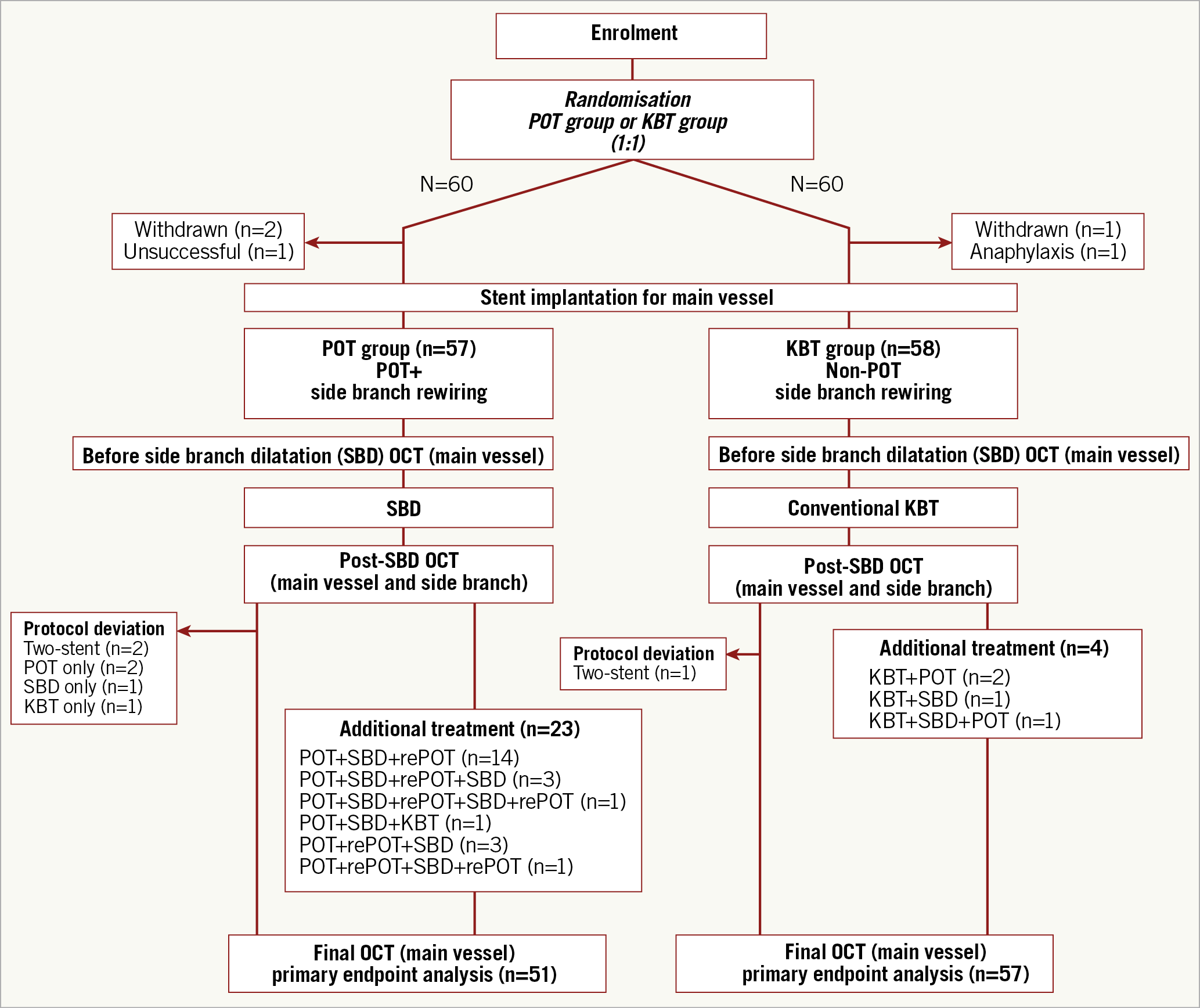

A total of 120 patients from 15 centres were enrolled and randomised between April 2016 and July 2018. Three patients withdrew consent, one patient had anaphylaxis, and one patient was excluded because of unsuccessful PCI due to wire perforation before stent implantation. Finally, 115 patients were analysed (POT group: 57 patients; KBT group: 58 patients).

All patients provided written informed consent. The study protocol was developed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This trial was registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN-ID: UMIN000019105) prior to enrolment initiation.

ENDPOINTS

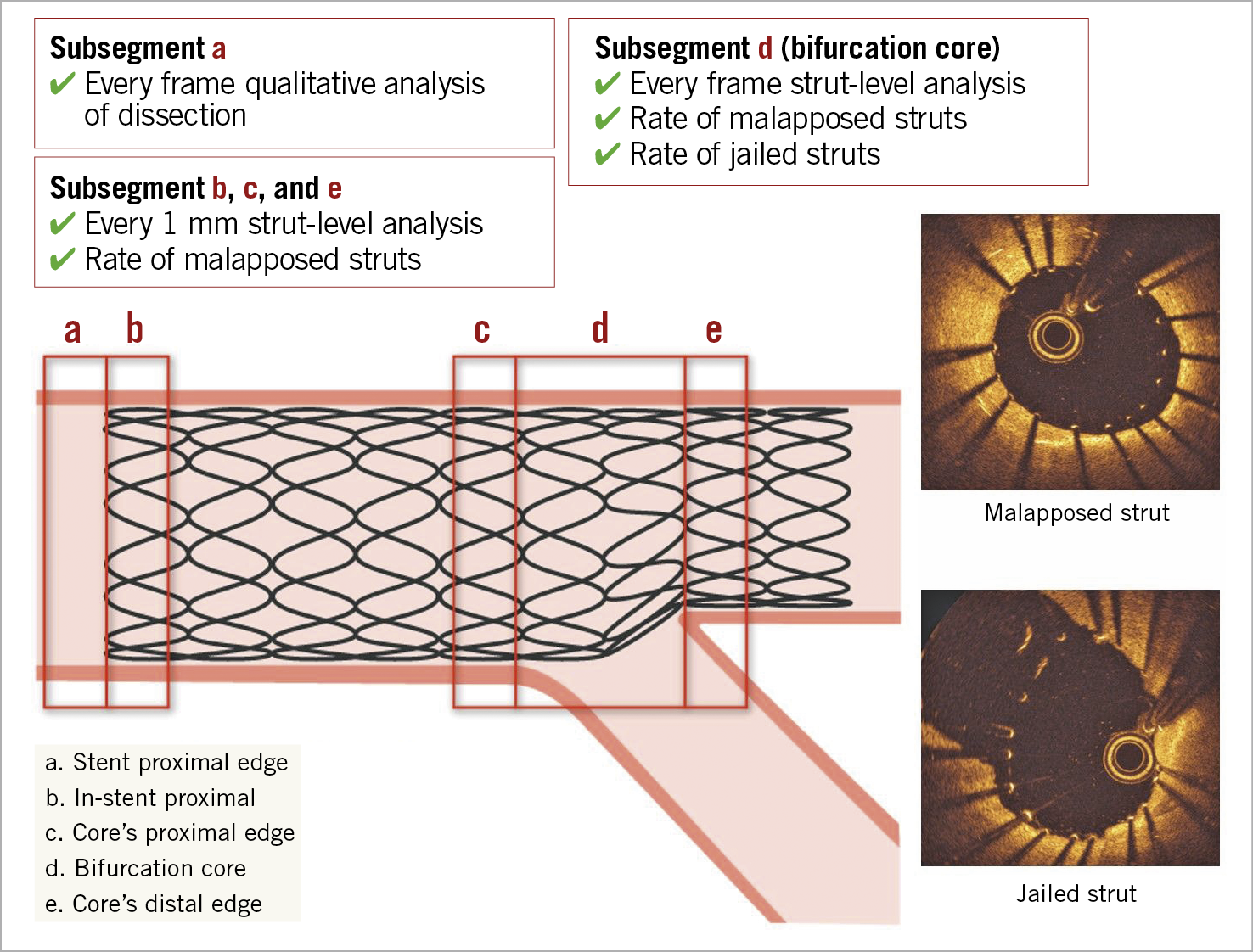

The primary endpoint was the rate of malapposed struts in each subsegment, assessed by final OCT (Figure 1). Secondary endpoints were stent and lumen area, stent eccentricity index, malapposition area/distance, proximal edge dissection assessed by final OCT, total procedural time, fluoroscopic time, amount of contrast, SB wire crossing time after MV stenting, death/cardiac death, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, clinically driven target lesion revascularisation (TLR), and target vessel revascularisation up to one year. Definite stent thrombosis was defined according to the Academic Research Consortium classification9. TLR was defined as repeat PCI revascularisation or target lesion surgery.

Figure 1. Trial profile. KBT: kissing balloon technique; OCT: optical coherence tomography; POT: proximal optimisation technique; SBD: side branch dilation

PCI PROTOCOL

All patients were treated with aspirin, clopidogrel, prasugrel, and periprocedural heparin in accordance with institutional policies.

POT GROUP

Crossover stenting was performed from the proximal to distal bifurcated MV in the lesion. Stent size was decided based on the distal MV reference diameter under visual or quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) guidance. Immediately after stent implantation, POT dilation was performed before SB wiring. POT balloon size was selected based on the proximal MV reference diameter. Locating the POT balloon distal marker at the carina was encouraged. The jailed wire technique for the SB was mandatory until guidewire recrossing, aimed at a distal cell of the jailed struts. SBD was performed using a short non-compliant balloon (length: 4-8 mm).

KBT GROUP

Crossover stenting was performed as in the POT group. The conventional KBT, in which MV and SB balloons were aligned at the proximal stent edge, was employed after changing the MV and SB wires10. KBT balloon size was selected by matching the MV and SB balloons to the distal MV and SB reference diameters, respectively.

OCT IMAGING

OCT imaging was performed with either the protocol-recommended frequency-domain OCT (ILUMIEN™ OCT imaging system; Abbott Vascular, Westford, MA, USA) or optical frequency-domain imaging (Lunawave®; Terumo Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Nitroglycerine or other vasodilators were used prior to OCT image acquisition. A high-resolution pullback mode with 100% contrast for blood clearance was recommended; low-molecular-weight dextran-L or lactated Ringer’s solution was allowed for renal failure patients. OCT images were obtained after z-offset calibration to include at least 5 mm distal and proximal edges of the target lesion. OCT image acquisition was performed before SBD, at the end of the procedure.

OTHER TECHNICAL CONSIDERATIONS

All procedures were performed under angiographic guidance. OCT results were not used for stent sizing. A provisional stenting strategy was mandatory. The SB stenting criterion was Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 0 or TIMI 1 SB flow after treatment, as previously reported7. To avoid fatal adverse events, additional treatment including re-POT or additional KBT was allowed after procedure completion for cases with stent malapposition >400 µm from the vessel wall in any part of the stent. The choice of additional treatment, re-POT or additional KBT, was at the operators’ discretion. Protocol deviation was defined as procedures in which the protocol was not completed, including the need for two stents, performing only POT, or only KBT or SBD without POT.

QCA ANALYSIS

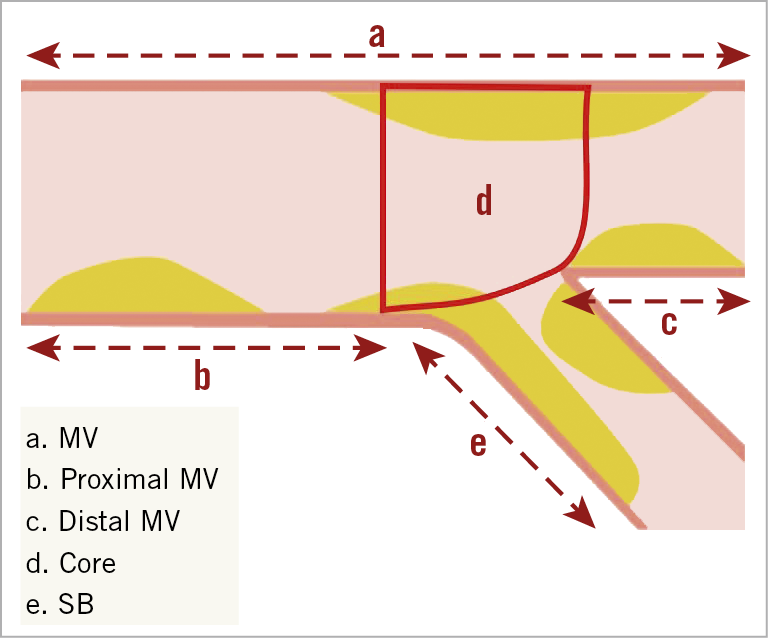

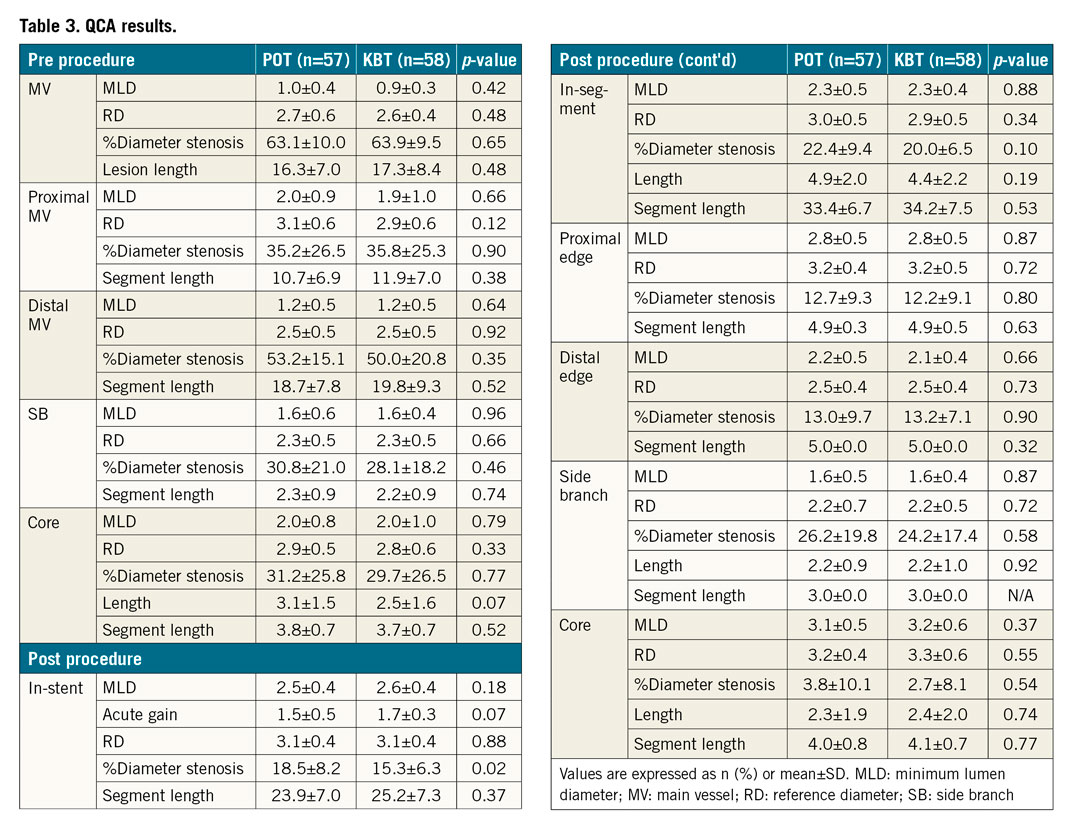

QCA was performed in an independent core laboratory (Cardiocore Japan, Tokyo, Japan) using a semi-automated bifurcation analysis software. QAngio® XA (Medis Medical Imaging Systems, Leiden, the Netherlands) was used11. For each subsegment, minimal lumen diameter, reference vessel diameter, percent diameter stenosis, and lesion length were measured before and at the end of the procedure, as previously reported11. Preprocedural analysis included five subsegments: MV, proximal MV, distal MV, bifurcation core, and SB (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Subsegment analysis by quantitative coronary angiography. MV: main vessel; SB: side branch

OCT IMAGE ANALYSIS

OCT image analysis was conducted using QIvus (Medis Medical Imaging Systems) in an independent core laboratory (Cardiocore Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Five subsegments were defined: proximal edge, in-stent proximal site, core’s proximal edge, bifurcation core, and core’s distal edge (Figure 3). Excluding the bifurcation core, subsegment lengths were 5 mm from the border, which was the end of the stent or bifurcation core. Quantitative analysis was performed for all frames except for measurements regarding the stent at the proximal edge. To compare subtle differences, quantitative analysis was conducted for every frame, especially at the bifurcation core subsegment. Otherwise, all quantitative analyses were performed at every 1 mm interval along the entire target segment. For quantitative strut-level analysis, malapposed strut rate and maximum malapposition distance were estimated for all subsegments except for the proximal edge, and the jailed strut rate only at the bifurcation core was determined. A jailed strut was defined as a strut floating at the SB orifice. Malapposition was adjudicated when the distance between the lumen and stent contour was greater than the strut thickness (Resolute Integrity: 91 µm; Resolute Onyx: 81 µm). Qualitative assessment for evaluation of edge dissection, including all visible ones irrespective of range or depth, was performed for all frames at the proximal edge.

Figure 3. Subsegment analysis by optical coherence tomography. Except for the bifurcation core (segment d), subsegment length was 5 mm from the border. The border denotes the end of the stent and bifurcation core. Strut-level analysis was performed for every frame, and the rate of jailed struts at the bifurcation core was estimated. Dissection at the proximal edge (subsegment a) and distal edge was adjudicated.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Sample size calculation was based on the assumption that the incidence of the primary endpoint would be 10.0% in the POT group and 35% in the KBT group7. Therefore, we estimated that 51 patients in each group would allow the trial to have 80% power with a two-sided alpha level of 0.05 (according to the chi-square test) to detect a significant difference in the primary endpoint. Compensation for 20% suboptimal imaging required enrolment of 60 patients per group. Analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat basis. Continuous variables were assessed for normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test and are expressed as mean±standard deviation or as median (interquartile range). Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test and are presented as numerical values and percentages. Depending on the distribution of variables, continuous variables were compared using an unpaired Student’s t-test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. All p-values were two-sided; p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analysed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

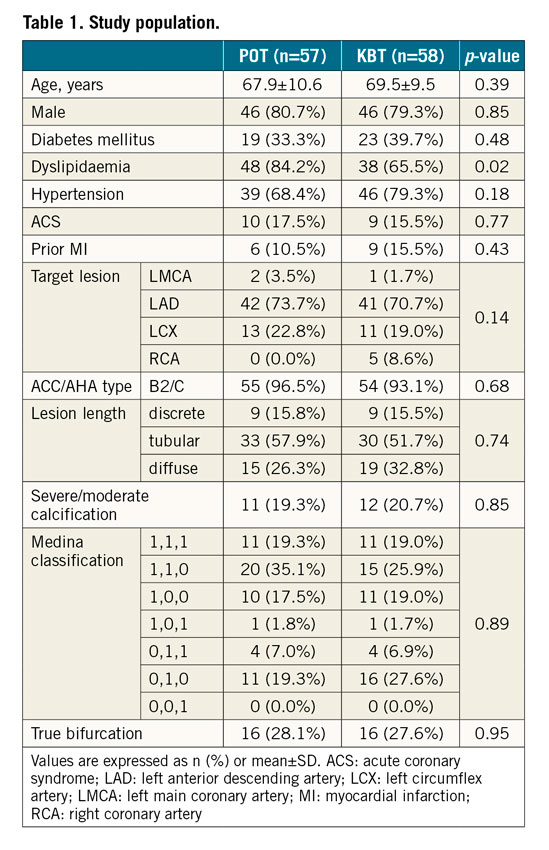

Baseline patient characteristics, lesion characteristics, Medina classification, and true bifurcation rate were similar between the groups (Table 1).

PROCEDURAL CHARACTERISTICS AND OUTCOMES

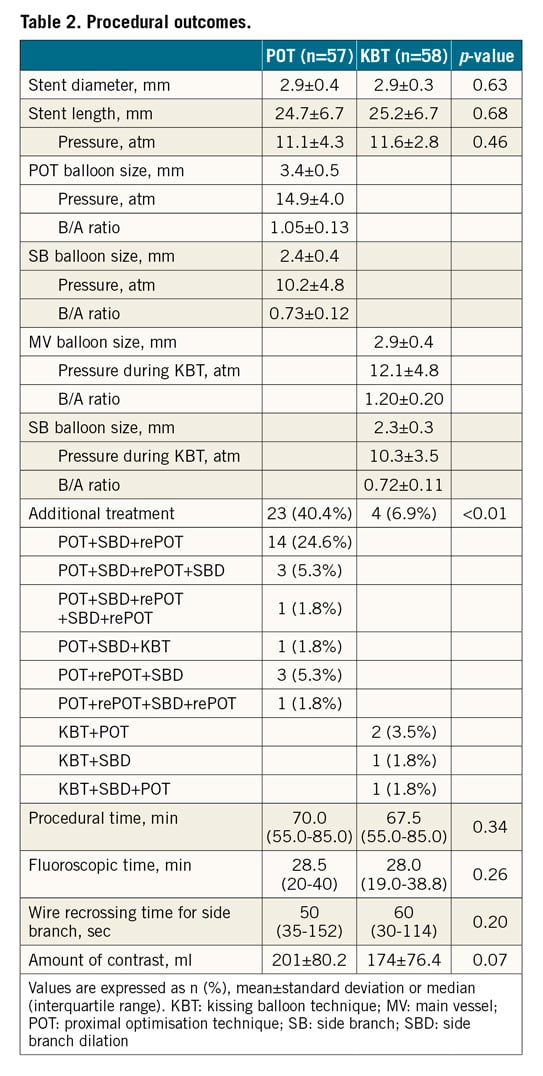

Procedural characteristics are presented in Figure 1. Procedural outcomes are summarised in Table 2. Stent diameter and length were not significantly different between the groups. In the POT group, the POT and SB balloon sizes were 3.4±0.5 mm and 2.4±0.4 mm, respectively. Furthermore, the POT and SB balloon/artery ratios, calculated using the reference diameter from the QCA analysis, were 1.05±0.13 and 0.73±0.12, respectively. In the KBT group, the MV and SB balloon sizes were 2.9±0.4 mm and 2.3±0.3 mm, respectively. Moreover, the MV and SB balloon/artery ratios were 1.20±0.20 and 0.72±0.11, respectively. Additional treatment was performed for 40.4% and 6.9% of patients in the POT and KBT groups, respectively (p<0.01). The POT+SBD+re-POT sequence most frequently required additional treatment in the POT group (24.6%). Protocol deviation was observed in 6 patients in the POT group and 1 in the KBT group. In the POT group, protocol deviations included the need for a second stent (n=2), POT only (n=2), SBD without POT (n=1), and KBT without POT (n=1). In the KBT group, protocol deviation included the need for a second stent (n=1). SB stenting was applied in 3.5% and 1.7% of patients in the POT and KBT groups, respectively (p=0.62). No significant differences in procedural time, fluoroscopic time, wire crossing time for the SB, and amount of contrast were noted between the groups.

QCA RESULTS

Results of preprocedural and post-procedural QCA measurements are presented in Table 3. No significant difference in preprocedural QCA measurements was observed between the groups. However, regarding post-procedural QCA measurements, in-stent percent diameter stenosis was higher in the POT group (18.5±8.2 vs 15.3±6.3, p=0.02).

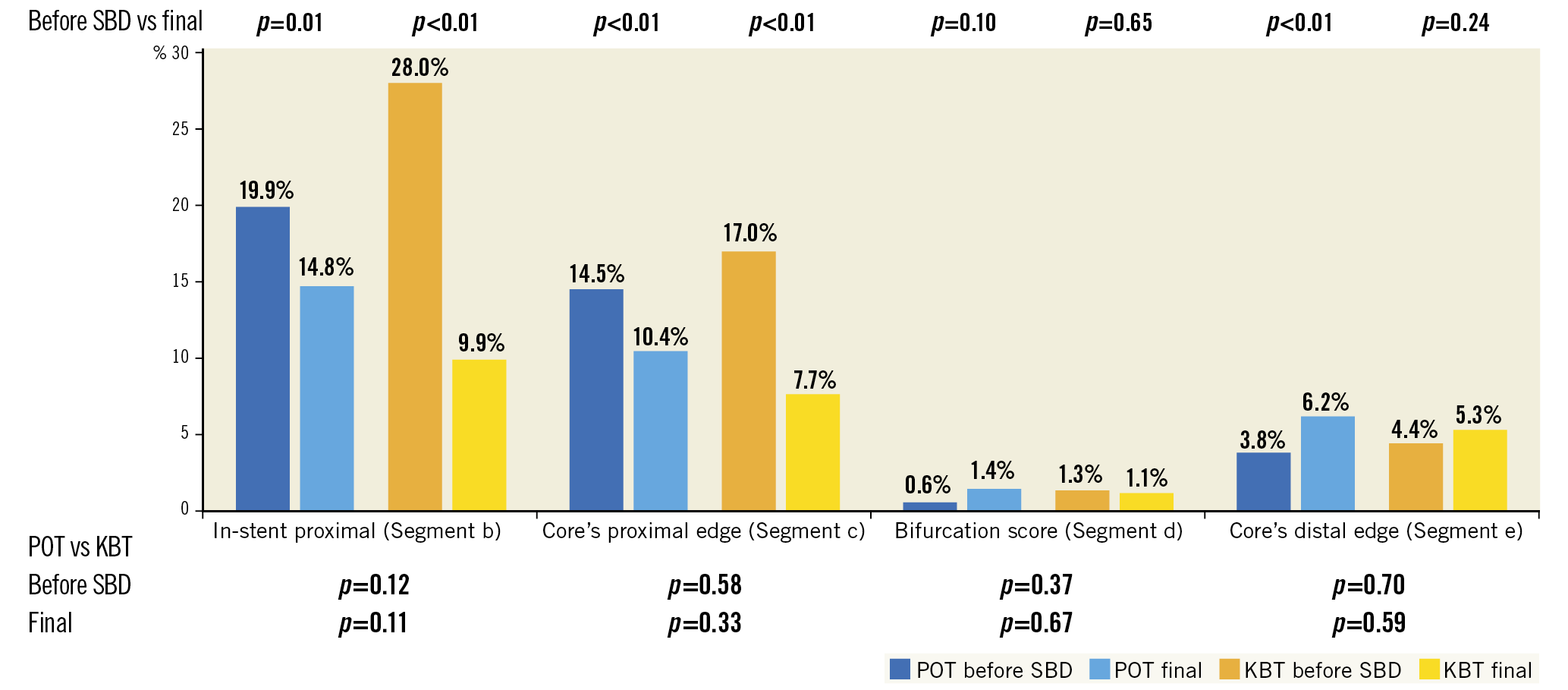

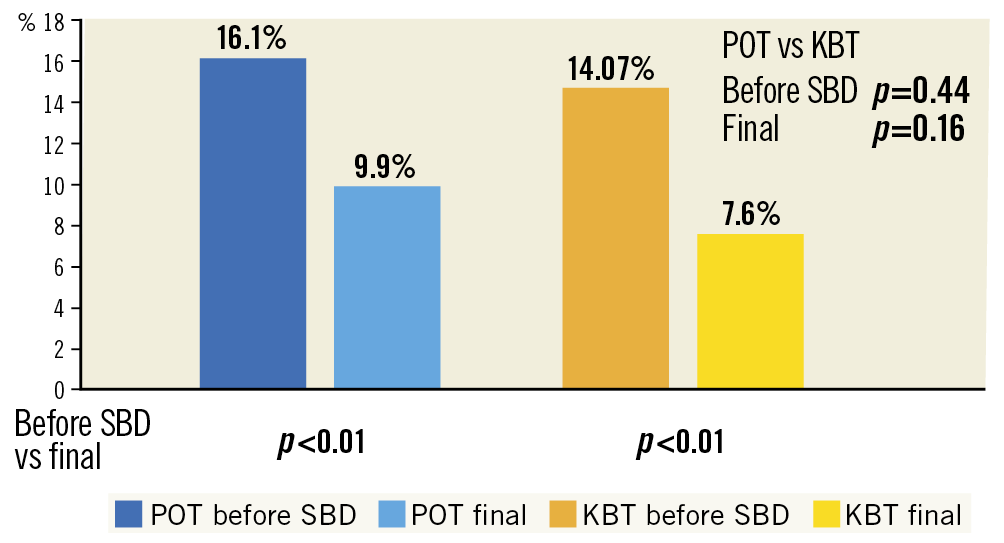

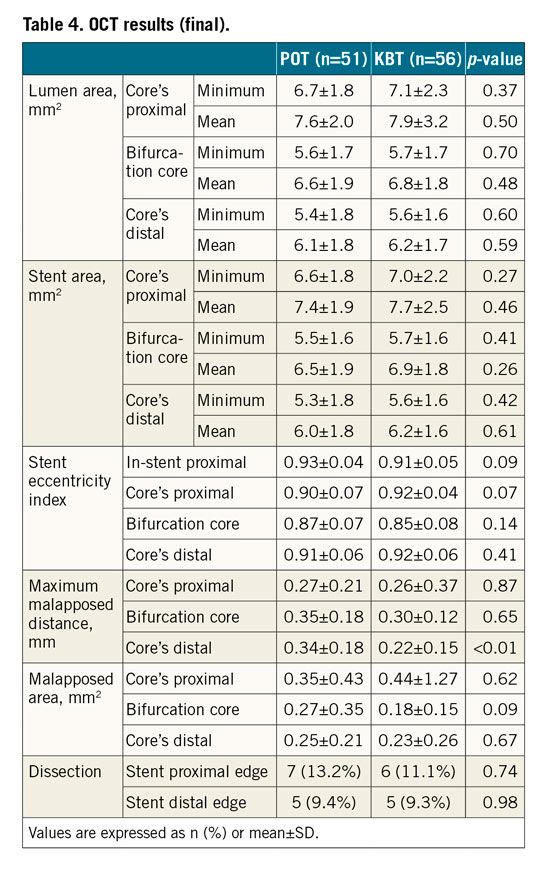

OCT RESULTS

The malapposed strut rate as assessed by final OCT, the primary endpoint, was 10.4% and 7.7% at the in-stent proximal site (Figure 3C, p=0.33), 1.4% and 1.1% at the bifurcation core (Central illustration, Figure 3D, p=0.67), and 6.2% and 5.3% at the core’s distal edge (Figure 3E, p=0.59) in the POT and KBT groups, respectively (Figure 4). The malapposed strut rate as assessed by pre-SBD OCT was 14.5% and 17.0% at the in-stent proximal site (Figure 3B, p=0.58) in the POT and KBT groups, respectively (Figure 4). The jailed strut rate at the bifurcation core, the secondary endpoint, was 16.1% and 14.7% (p=0.44) by pre-SBD OCT and 9.9% and 7.6% (p=0.16) by final OCT in the POT and KBT groups, respectively (Central illustration, Figure 5). Lumen area, stent area, and stent eccentricity index in the final OCT were not significantly different between the POT and KBT groups (Table 4). The maximum malapposition distance of the core’s distal edge (Figure 3E) as assessed by final OCT was greater in the POT group (0.34±0.18 vs 0.22±0.15, p<0.01). The dissection rates at the proximal (Figure 3A) and distal edges (Table 4) were not significantly different between the groups.

Central illustration. An overview of the PROPOT trial. Malapposed strut rate assessed by final OCT, the primary endpoint of this study, was 1.4% and 1.1% at the bifurcation core (p=0.67). Jailed strut rate at the bifurcation core was 9.9% and 7.6% (p=0.16) by final OCT in the POT and KBT groups, respectively. KBT: kissing balloon technique; OCT: optical coherence tomography; POT: proximal optimisation technique

Figure 4. Rate of malapposed struts at each segment before side branch dilation and at the end of the procedure. KBT: kissing balloon technique; POT: proximal optimisation technique; SBD: side branch dilation

Figure 5. Rate of jailed struts at the bifurcation core before side branch dilation and at the end of the procedure. KBT: kissing balloon technique; POT: proximal optimisation technique; SBD: side branch dilation

PROCEDURAL OUTCOMES

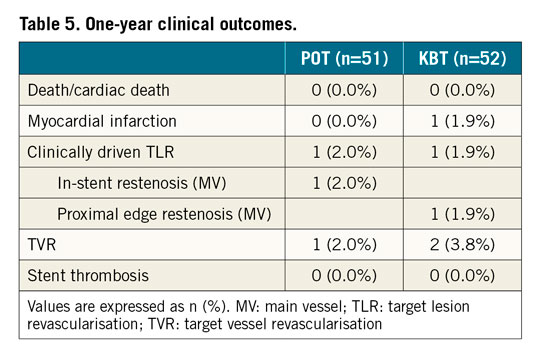

One-year clinical outcomes are summarised in Table 5. No death or cardiac death was observed in either group. One patient (1.9%) in the KBT group had a myocardial infarction. Clinically driven TLR was performed for one patient in each group (2.0% vs 1.9%). The TLR site was located in the MV in both groups. Target vessel revascularisation was performed for one patient (2.0%) in the POT group and two (3.8%) in the KBT group. No patient had stent thrombosis in either group.

Discussion

This is the first prospective, open-label, randomised study to investigate whether POT is superior in terms of stent apposition compared with the conventional KBT in real-life bifurcation lesions using OCT. The main findings were the following. (1) Malapposed strut rates around the bifurcation were not significantly different between the POT and KBT groups. (2) Jailed strut rates at the SB ostium before SB treatment or at final OCT did not differ between the groups. (3) No significant differences in stent area, stent eccentricity index, dissection rate, procedural time, fluoroscopic time, SB wire crossing time, and amount of contrast were observed between the groups. (4) One-year clinical outcomes were excellent in both groups.

Provisional stenting followed by KBT as bifurcation lesion treatment is widely used in clinical practice. Although a limited advantage regarding SB restenosis reduction has been reported4, randomised controlled trials comparing one-stent strategies with or without KBT showed no advantage12 or an adverse effect13 on clinical outcomes. Hence, KBT efficacy remains controversial. In bench testing, KBT has a potential risk of ellipsoid stent deformation and MV overexpansion, leading to coronary dissection of the proximal part of the stent3. In previous studies, elliptical MV overexpansion resulted in more frequent MV reintervention2,14.

POT involves dilation of a short balloon at the proximal segment of the stent for apposition to the MV before SB wiring. This enables easier wire access to the SB and reduces distortion and stent strut malapposition5,6. Although this technique’s efficacy has been confirmed in bench testing, clinical evidence is limited7,8. In this study, POT and SBD did not show any advantage over conventional KBT regarding stent apposition and procedural convenience. The malapposition rate for each OCT timing, either after wire recrossing or after SB treatment, did not significantly differ between groups. Furthermore, the final stent area was similar in both groups, and no clinical benefits were gained in procedural time, SB wire crossing time, or amount of contrast.

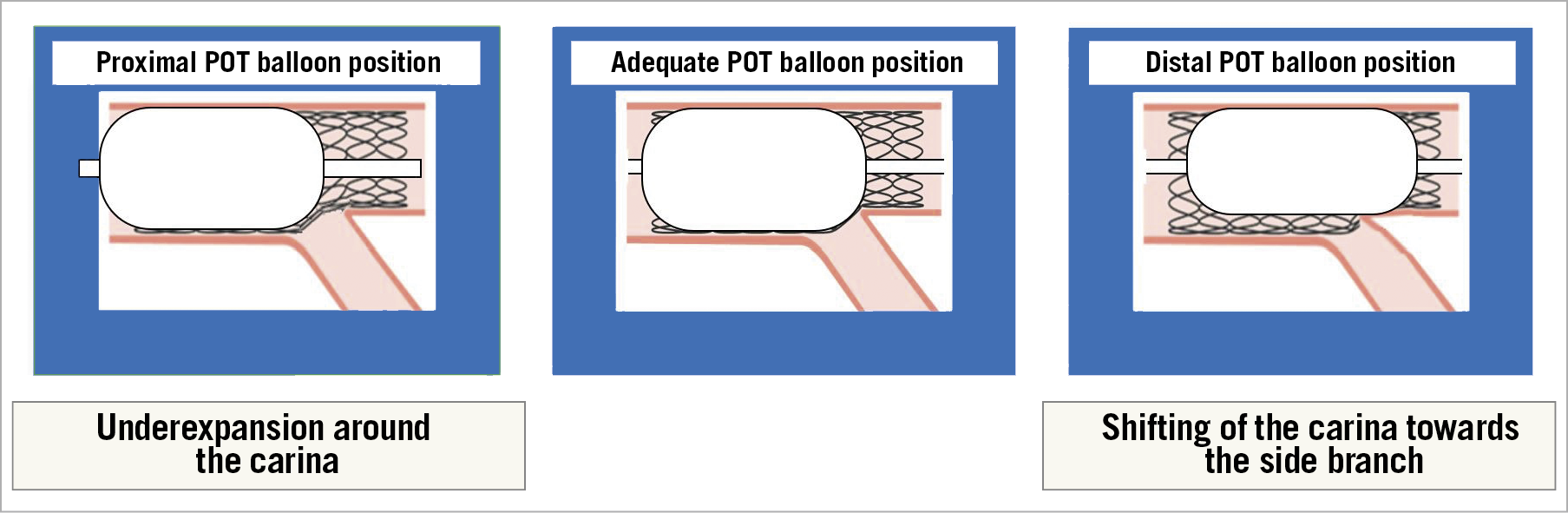

Possible reasons for the non-superiority of POT followed by SBD over conventional KBT include the following. (1) The POT balloon might not have been correctly placed; the distal marker and balloon shoulder were not placed just at the carina. (2) Visualisation of the actual part of the carina by angiography was not correct. (3) KBT balloon size was large enough to effectively reduce malapposition at the proximal MV and bifurcation core. A previous study using bench testing suggested that appropriate POT balloon positioning is essential to avoid a carina shift15. Inappropriate distal location of the POT balloon risks distal MV overstretch and carina shift to the SB, while inappropriate proximal location may lead to stent malapposition and underexpansion around the carina16 (Figure 6). Nonetheless, in daily clinical practice, visualisation of the actual part of the carina by angiography is difficult due to foreshortening or vessel overlap. For suitable POT performance, intracoronary imaging is useful for accurate carina identification; however, the identification of the actual part of the carina is still a challenging issue given the anatomical complexity that cannot be fully captured even with the use of a single intracoronary imaging modality17. Regarding carina shift prevention, KBT is more reliable than POT followed by SBD15. Using adequately sized KBT balloons could also reduce malapposition at the proximal MV and bifurcation core at a level similar to that after POT. In this study, operators were likely to select a larger balloon for the MV in the KBT group because the MV balloon/artery ratio was significantly greater than the POT balloon/artery ratio (1.20±0.20 vs 1.05±0.13, p<0.01). However, they selected a relatively smaller balloon with a similar balloon/artery ratio for the SB in both groups (0.73±0.12 vs 0.72±0.11, p=0.41) (Table 2). Consequently, favourable outcomes regarding rates of malapposed struts and jailed struts were observed in the KBT group.

Figure 6. Importance of POT balloon position. POT: proximal optimisation technique

In our study, additional treatment was performed for 40.4% of the POT group, 24.6% of which underwent re-POT. The POT+SBD+re-POT sequence is generally recommended for correcting carina deviation or stent deformation induced by SBD18. However, it risks jailed strut re-protrusion or SB ostial area narrowing after re-POT across the SB ostium19,20. While POT followed by SBD seems to be a simple strategy, additional treatment is more frequently required and intravascular imaging is necessary for optimal POT balloon size selection and its positioning, and correction of SBD-induced stent deformation.

The guidewire recrossing point into the stent-jailed SB would also have affected both POT and KBT results in this study. Previous studies showed that selecting the distal recrossing point under 3D-OCT guidance was effective in achieving a better SB opening and stent apposition for link-free stent types21,22. Although this study did not include a protocol for the illustration of the wire recrossing point, it was adjusted under 3D-OCT guidance in several participating institutes, which might have contributed to the excellent clinical outcomes in both groups.

One-year outcomes in this study were excellent, and major adverse clinical events were observed in only 3% of patients across both groups. TLR performance had an acceptably low incidence and was limited to the MV despite routine SB treatment. Treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions using an adequately sized balloon and optimisation under OCT guidance might result in good clinical outcomes for both POT and KBT.

Limitations

This randomised study had an open-label design and included a small number of patients. Furthermore, operators and patients were aware of the technique used, potentially introducing bias and/or affecting procedural results. Clinical implications of OCT-guided surrogate imaging endpoints are unknown and limited; nonetheless, previous studies showed that stent malapposition was associated with stent failure and thrombosis23,24. Target lesions were mainly located in the left anterior descending artery; left main lesions accounted for only 1.7-3.5%, which may not reflect a certain benefit derived from POT in bifurcations with large vessel tapering. Although regulated in the protocol, several device-related variables (e.g., balloon size, length, pressure, and non-compliant-type), as well as procedural variables (e.g., the position of the POT and KBT balloons, and the sequence of balloon inflation for KBT) might have influenced the results. Additionally, higher protocol deviation rates in the POT group (10.4% vs 1.7% in the KBT group) might have affected results. The degree of operator skill was inherent and could have led to technical bias or affected procedural decisions. Post-PCI OCT data were obtained after the final procedure, which did not completely reflect conditions immediately after POT or KBT. The protocol recommended angio-guided device selection; however, performing OCT in every phase would affect device selection and procedural decisions, irrespective of whether additional treatment was performed or not. Additional treatment was carried out only in case of stent malapposition >400 µm from the vessel wall in any part of the stent to avoid future adverse events; however, it might significantly affect the results, and might not allow generalisability to a non-OCT-guided PCI.

Conclusions

In this randomised study, regarding treatment following crossover stenting in coronary bifurcation lesions, POT followed by SBD did not show any advantages over conventional KBT in terms of stent apposition or procedural convenience; however, excellent midterm clinical outcomes were observed in both strategies. Further trials are required to confirm the long-term clinical benefit of POT for bifurcation lesions.

|

Impact on daily practice This is the first randomised study to investigate whether POT is superior in terms of stent apposition compared with the conventional KBT in bifurcation lesions using OCT. Malapposed strut and jailed strut rates around the bifurcation were not significantly different between the POT and KBT groups. One-year clinical outcomes were excellent in both strategies. Further trials are required to confirm the long-term clinical benefit of POT for bifurcation lesions. |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Yasuyuki Maruyama for his role in the data and safety monitoring board for this study. We also thank Dr Takaaki Isshiki for his role in the clinical events committee.

Funding

This study was funded by Medtronic Japan Co. Ltd.

Conflict of interest statement

N. Suzuki has received speaker fees from Abbott Vascular, Actelion Pharmaceuticals, Astellas, Astellas-Amgen, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Nipro, Otsuka, Sanofi and Toa Eiyo. Y. Numasawa reports personal fees and lecture fees from Abbott and Terumo, and being a consultant for Nipro. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.