Abstract

The rearrangement of healthcare services required to face the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic led to a drastic reduction in elective cardiac invasive procedures. We are already facing a “second wave” of infections and we might be dealing during the next months with a “third wave” and subsequently new waves. Therefore, during the different waves of the COVID-19 pandemic we have to face the problems of how to perform elective cardiac invasive procedures in non-COVID patients and which patients/procedures should be prioritised. In this context, the interplay between the pandemic stage, the availability of healthcare resources and the priority of specific cardiac disorders is crucial. Clear pathways for “hot” or presumed “hot” patients and “cold” patients are mandatory in each hospital. Depending on the local testing capacity and intensity of transmission in the area, healthcare facilities may test patients for SARS-CoV-2 infection before the interventional procedure, regardless of risk assessment for COVID-19. Pre-hospital testing should always be conducted in the presence of symptoms suggestive of SARS-CoV-2 infection. In cases of confirmed or suspected COVID-19 positive patients, full personal protective equipment using FFP 2/N95 masks, eye protection, gowning and gloves is indicated during cardiac interventions for healthcare workers. When patients have tested negative for COVID-19, medical masks may be sufficient. Indeed, individual patients should themselves wear medical masks during cardiac interventions and outpatient visits.

Introduction

The rearrangement of healthcare services required to face the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic led to drastic reductions of elective cardiac invasive procedures1. Regions in Europe differ substantially in terms of local healthcare resources, pandemic extent, phase of the COVID-19 outbreak, changes of the pandemic over time and therefore access to healthcare services other than COVID-19 care. During the “first wave”, these variations had a wide range of implications for regional healthcare services, national healthcare authorities and in-hospital redistribution of resources.

We are now in a phase of the COVID-19 pandemic whereby some countries are already facing a “second wave” of infections and we might be dealing during the coming months with a “third wave” and subsequently new waves of infection. Therefore, we have to face the problems of how to perform elective cardiac invasive procedures in non-COVID patients and which patients/procedures should be prioritised during the different waves of the COVID-19 pandemic2. Simultaneously, during these phases, protocols that provide maximum safety of patients and healthcare workers (HCWs) during the hospitalisation and procedures require to be designed. The European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) has assembled a panel of interventional cardiologists with first-hand experience from affected areas, representatives of heavily, moderately and marginally affected countries and expertise in network organisation. The objective of this position statement is to define algorithms for safe performance of elective cardiac procedures according to the local extent and phase of the pandemic and available resources to prioritise patient work-up and procedures.

This statement reflects the official position of the EAPCI, meant to provide an overall guidance that should be adapted to the local situation and regulations.

IMPACT OF EPIDEMIOLOGIC VARIATIONS AMONG COUNTRIES ON CARDIAC INVASIVE PROCEDURES DURING THE COVID-19 OUTBREAK

The epidemiologic situation was not uniform within each individual European country, suggesting that considerations should be made at regional rather than at national levels. Despite these premises, the responses of the healthcare systems to the “first wave” were rather uniform and in line with the EAPCI strategic categorisation of cardiovascular interventions1. Healthcare systems were re-organised to separate as much as possible “hot” (dedicated to positive or suspected COVID-19 patients) from “cold” pathways (COVID-19 negative). In some regions, this occurred at the hospital level, with fully dedicated COVID-19 hospitals, while in others the separation was done within the same hospital, with COVID-19 dedicated wards and catheterisation laboratories3. In this latter case, the access and in-hospital path of the COVID-19 patients was, in general, physically separated from the path of the other patients. Given the often occult presentation of COVID-19, characterised by delayed clinical presentation from the time of contagion, at times with complete lack of symptoms, “cold” sites were sometimes affected by infections within the workforce and asymptomatic patients. This led to recurrent and temporary closures of the cold sites, disinfection, quarantine of the HCWs and patients involved, with a major impact on the regular healthcare services.

Elective structural and coronary procedures were in general put on hold and/or postponed during the “first wave” in order to increase the critical mass of HCWs available and to free intensive care unit (ICU) beds for patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia requiring mechanical ventilation4. Acute cardiovascular procedures, mostly in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and unstable or high-risk non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), were overall preserved. Interestingly, a general trend of 20-50% fewer STEMI cases was observed in many regions, which could be a consequence of the public campaign requesting the population “to stay at home”. Other factors linked to the lockdown (e.g., reduced pollution, reduced physical activity and stress, etc.) are also discussed in this context5,6,7. Importantly, HCWs reported a surge of mechanical complications of STEMI, most probably related to delayed presentation of the patients, and less frequently to a shift in the reperfusion therapy towards thrombolysis in some circumstances8,9,10,11.

While most healthcare systems returned to a certain routine clinical activity after the “first wave” of the pandemic with resumption of elective cardiovascular procedures, we are already facing the “second wave” of infections, and we cannot exclude that we may be facing new waves of infections in the upcoming months. In this position statement only elective invasive cardiac procedures for non-COVID patients will be discussed, since emergent procedures have been discussed previously1.

KEY MESSAGES

– The EAPCI position to postpone cardiovascular procedures in stable patients to unload HCWs and intensive care beds during the “first wave” of the COVID-19 pandemic was aligned with most European healthcare system recommendations.

– While most healthcare systems returned to a certain level of routine clinical activity with resumption of elective cardiovascular procedures, we are now facing the “second wave” or new waves of infections.

PERFORMING ELECTIVE CARDIAC INVASIVE PROCEDURES TAKING INTO ACCOUNT THE PANDEMIC STAGE, RESOURCES AND PATIENTS/PROCEDURES TO PRIORITISE

The invasive management of acute coronary syndromes during the COVID-19 pandemic is beyond the scope of this document and has been covered elsewhere1. Recovery plans of elective procedures should consider three different variables:

1. Pandemic stage.

2. Availability of healthcare resources (including capacity of ICUs).

3. Patients/procedures to prioritise.

The pandemic stage in a given region should be quantified taking into account the number of infections per thousand people, the “growth rate”, number of cases requiring hospitalisation in general wards and ICUs per thousand people, and the degrees of transmission classified into the following categories according to World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation:

a. No case: with no confirmed case.

b. Sporadic cases: with one or more cases, imported or locally detected.

c. Cluster of cases: experiencing cases, clustered in time, geographic location and/or by common exposures.

d. Community transmission: experiencing larger outbreaks of local transmission defined through an assessment of factors including, but not limited to: large numbers of cases not linkable to transmission chains; large numbers of cases from sentinel lab surveillance; and/or multiple unrelated clusters in several areas of the country/territory/area.

Of note, the estimation of the “growth rate” is heavily influenced by the testing strategy and the test capacity in different regions; therefore, the evaluation of the number of hospitalised patients remains crucial to identify the degree of COVID-19 transmission and to scale the catheterisation laboratories’ capacity for elective cases.

The availability of healthcare resources should be assessed essentially by taking into account (net of any re-allocation) the number of beds in non-ICUs and ICUs per population, as well as the number of ventilators, amount of personal protective equipment (PPE), number of HCWs and budget resources to invest. A recommended threshold of available ICU capacity should be provided by regional institutions.

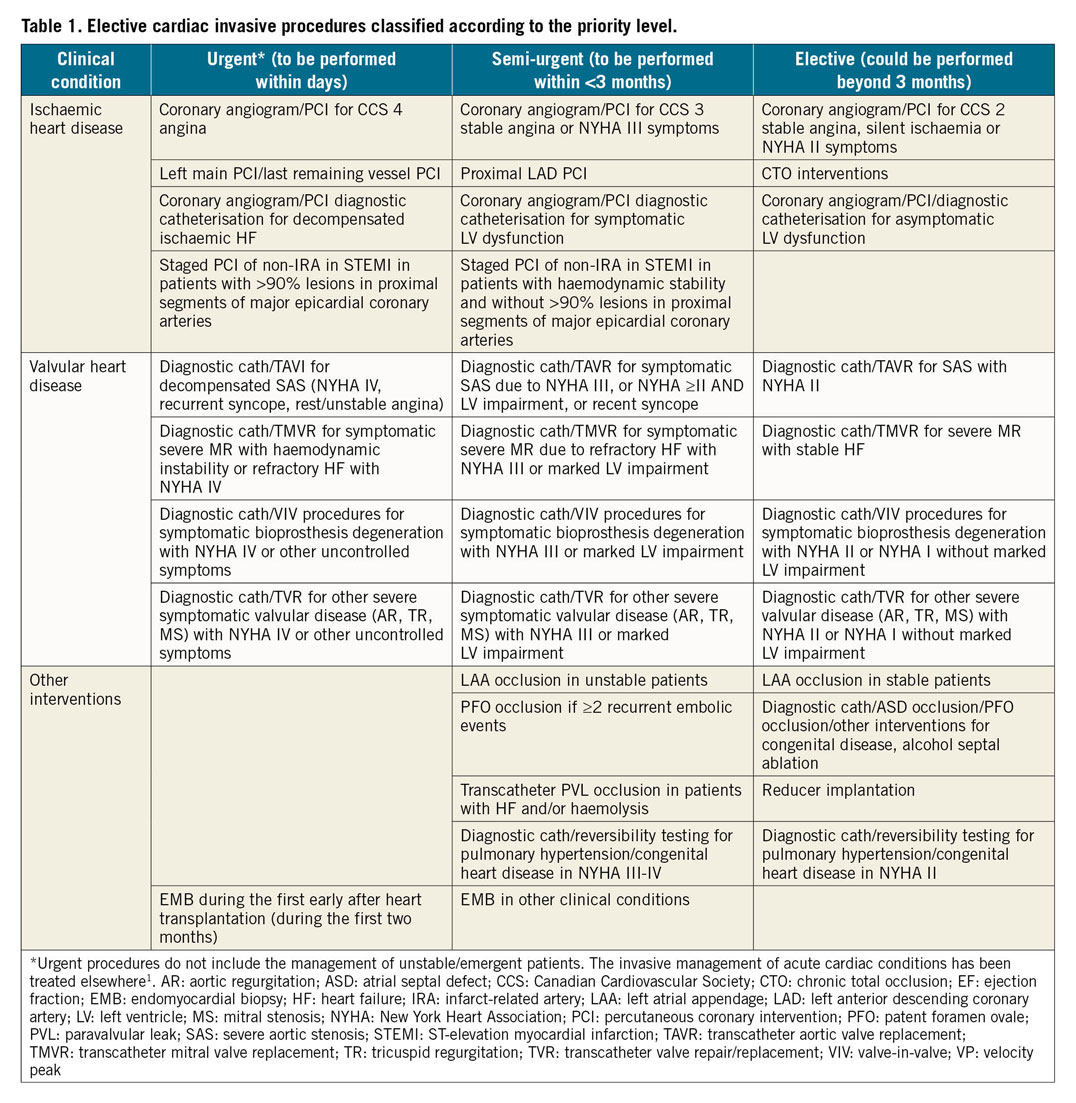

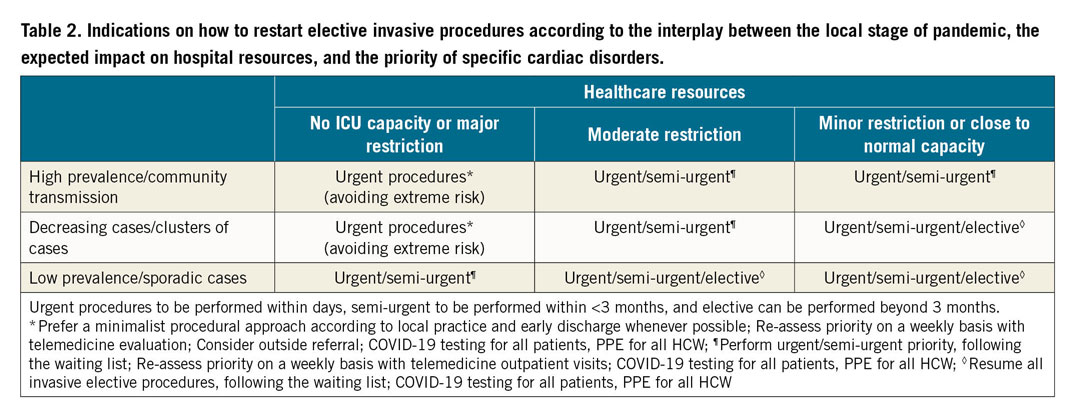

The third parameter (patients/procedures to prioritise) includes a careful evaluation of the number of patients on waiting lists and the accumulated delay, as well as the type of the cardiovascular disease requiring invasive procedures and the severity of symptoms (risk of mortality, morbidity and hospitalisation of that patient in the short and medium term, if not treated), and other patient conditions (age and comorbidities) impacting on the length of stay after intervention. Procedures could be divided into three levels: urgent (to be performed within days), semi-urgent (to be performed within <3 months) and elective (could be postponed beyond 3 months)2,12,13,14. Table 1 summarises cardiac conditions requiring invasive procedures according to these levels. The use of potential alternatives to invasive angiography (e.g., coronary computed tomography) should be taken into account whenever possible.

From the interdependence of these three variables, different clinical scenarios in planning elective invasive procedures can be assumed in non-COVID patients during different waves of infection. The worst situation occurs when the majority of available healthcare resources are dedicated to the COVID-19 pandemic in countries experiencing new waves of infections. In this scenario, cardiac invasive procedures should be performed after a careful assessment of the risk/benefit profile. On the other hand, in the best possible clinical scenario, when the number of infections is low and/or the impact on hospital resources is trivial, all invasive cardiac procedures can be planned.

Detailed suggestions on how to plan elective invasive procedures according to the interplay between the local stage of the pandemic, the expected impact on hospital resources, and the priority of specific cardiac disorders are summarised in Table 2 and Figure 1.

Figure 1. Decisional algorithm on how to perform elective invasive procedures according to the priority of cardiac disorders and the interplay among different stages of the pandemic and hospital resource availability. Urgent: to be performed within days. Semi-urgent: to be performed within <3 months. Elective: could be performed beyond 3 months.

KEY MESSAGES

– Recovery plans for elective invasive procedures should consider the interplay between the pandemic stage, the availability of healthcare resources and the priority of specific cardiac disorders.

– All waiting list patients should be prioritised according to clinical criteria (severity of symptoms and disease) with a recurring evaluation if necessary (telemedicine/outpatient consultation).

WHICH PATIENTS AND PROCEDURES TO PRIORITISE – FROM ETHICS TO EVIDENCE-BASED MEDICINE

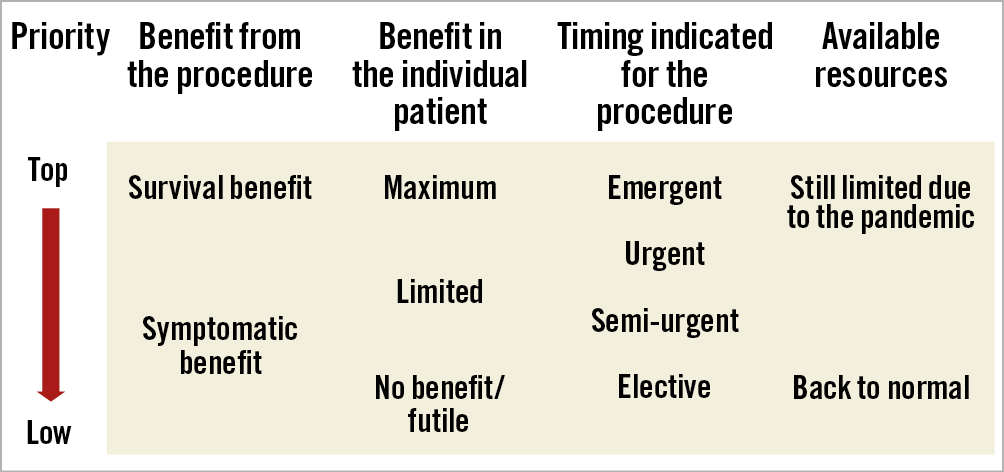

The decision regarding which patients and procedures to prioritise is challenging, both from a medical and an ethical perspective, and depends on the expected benefit from the procedure (survival vs symptomatic benefit), the degree of urgency required (urgent, semi-urgent and elective) as well as the available resources (HCWs, equipment, hospital beds, and financial resources) (Table 1, Figure 2).

Figure 2. Interplay among expected benefit from the procedure, degree of urgency required and available resources in decision making on which patient and procedure to prioritise. Urgent: to be performed within days. Semi-urgent: to be performed within <3 months. Elective: could be performed beyond 3 months

The highest priority should be given to urgent procedures with documented prognostic benefit. These are described in Table 1,15. Intermediate priority should indeed be given to semi-urgent procedures, as defined in Table 1.

Importantly, the benefit of a certain procedure should be put in the context of the individual patient and may range from maximum to limited or none, in terms of both life expectancy and quality of life. Factors such as age, comorbidities and life expectancy should also be taken into account during waves of the COVID pandemic where there is a paucity of beds, and similar considerations should also be taken into account in COVID-19 positive patients who are hospitalised for pneumonia.

While the estimated benefit from a specific procedure to the individual patient should be the first prioritisation criterion allowing the maximisation of the benefits, additional ethical criteria should guide the process of restarting an interventional activity. The process should be fair, meaning that within an institution, but ideally also within city and region, the criteria for decision making should be the same, though amongst different regions the restarting process may differ based on residual COVID-19 spread. Finally, patients should have the same access to cardiac procedures, regardless of medical insurance status, gender, ethnicity, and religious or political beliefs.

KEY MESSAGES

– The decision as to which patient and procedure to prioritise depends on the expected benefit from the procedure, the degree of urgency required and the available resources.

– The highest priority should be given to urgent procedures with documented prognostic benefit.

– Intermediate priority should be given to semi-urgent procedures.

MINIMISING PATIENT DELAY IN TREATMENT, WITH RESTORATION OF REASSURANCE AND SAFETY FOR BOTH PATIENTS AND HEALTHCARE WORKERS

The primary objective is to ensure the treatment of acute patients without delay, and to ensure that chronic patients are not left unsupported until their condition worsens.

The key priorities in the implementation of services during the COVID-19 outbreak are therefore twofold: first, to meet regional concerns about the reduced ability to progress with elective procedures due to social distancing, reduced capacity in the clinical areas available (some for reconfiguring of services, some to provide distance between patients), etc., and second, to reassure those individuals who require medical help that they will be treated safely.

Thus, communication is of particular importance, in particular since the precise instructions may change depending on the local and regional situation. In this context it is also important to highlight both the necessity to treat acute symptoms immediately and the fact that any delay in an acute cardiac situation can be fatal. This requires a combined effort from the public administration, scientific societies, hospitals, and referring physicians.

The appreciation of which measures are required to restore elective services in a responsible way will depend greatly on the local situation. If the local incidence of COVID-19 positive patients is low, attention will be directed much more to the clinical and epidemiologic side of the infection, while, in case of a high incidence, rigorous testing may be required.

Three objectives need to be considered:

1. To minimise the delay for the patients.

2. To ensure the separation of COVID-19 positive and negative patients.

3. To ensure the safety of the medical staff.

It is advisable, in the interest of the patients, to guarantee elective services, as soon as all parties assume that the local situation is favourable.

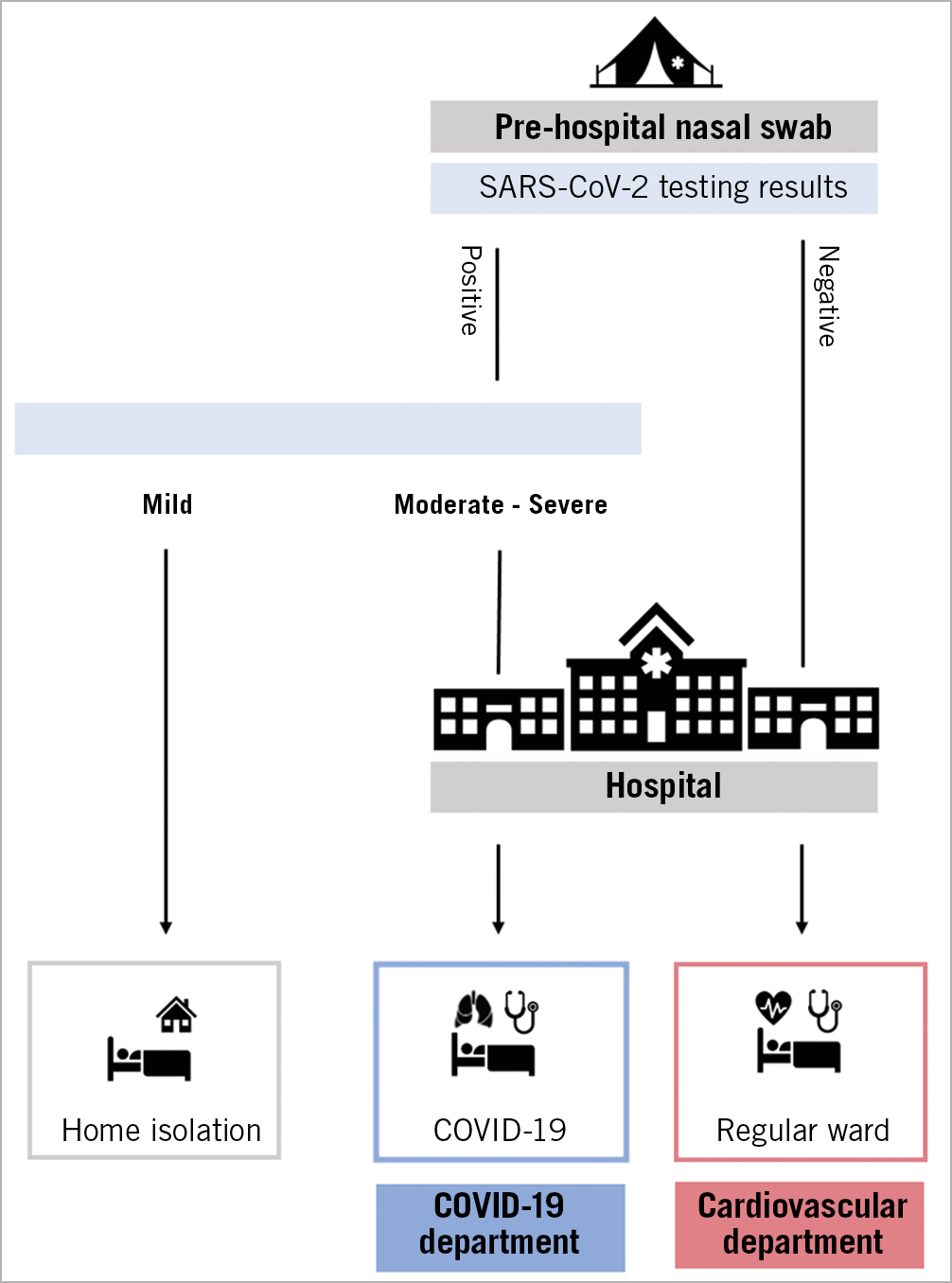

In any case, there need to be clear pathways for “hot” (COVID-19 positive) or presumed “hot” patients and “cold” patients in all hospitals (Figure 3). This can be achieved within the same institution or by the separation of “cold” centres for those routine patients with no risk of COVID-19. This latter organisation requires a regionally harmonised approach and specific attention to inter-institutional cooperation.

Figure 3. Hospital pathways during the COVID-19 pandemic for hot and cold areas. Patients with elective indications to percutaneous cardiac interventions undergo pre-hospital testing. If tested negative for COVID-19, they are admitted to cold areas (regular wards) of the hospital in order to undergo percutaneous cardiac interventions. If tested positive, according to symptoms, they will be sent to home isolation or admitted to hot areas (COVID-19 ward) in order to be treated for complications of the infection.

The implementation of pre-hospital triage is of utmost importance. This includes a symptom status questionnaire for all patients, optionally a temperature check.

ENSURE PATIENT SAFETY

According to WHO recommendations, testing in areas with community transmission must be prioritised and focused on the early identification and protection of vulnerable patients undergoing surgical procedures16.

PRE-HOSPITAL TESTING

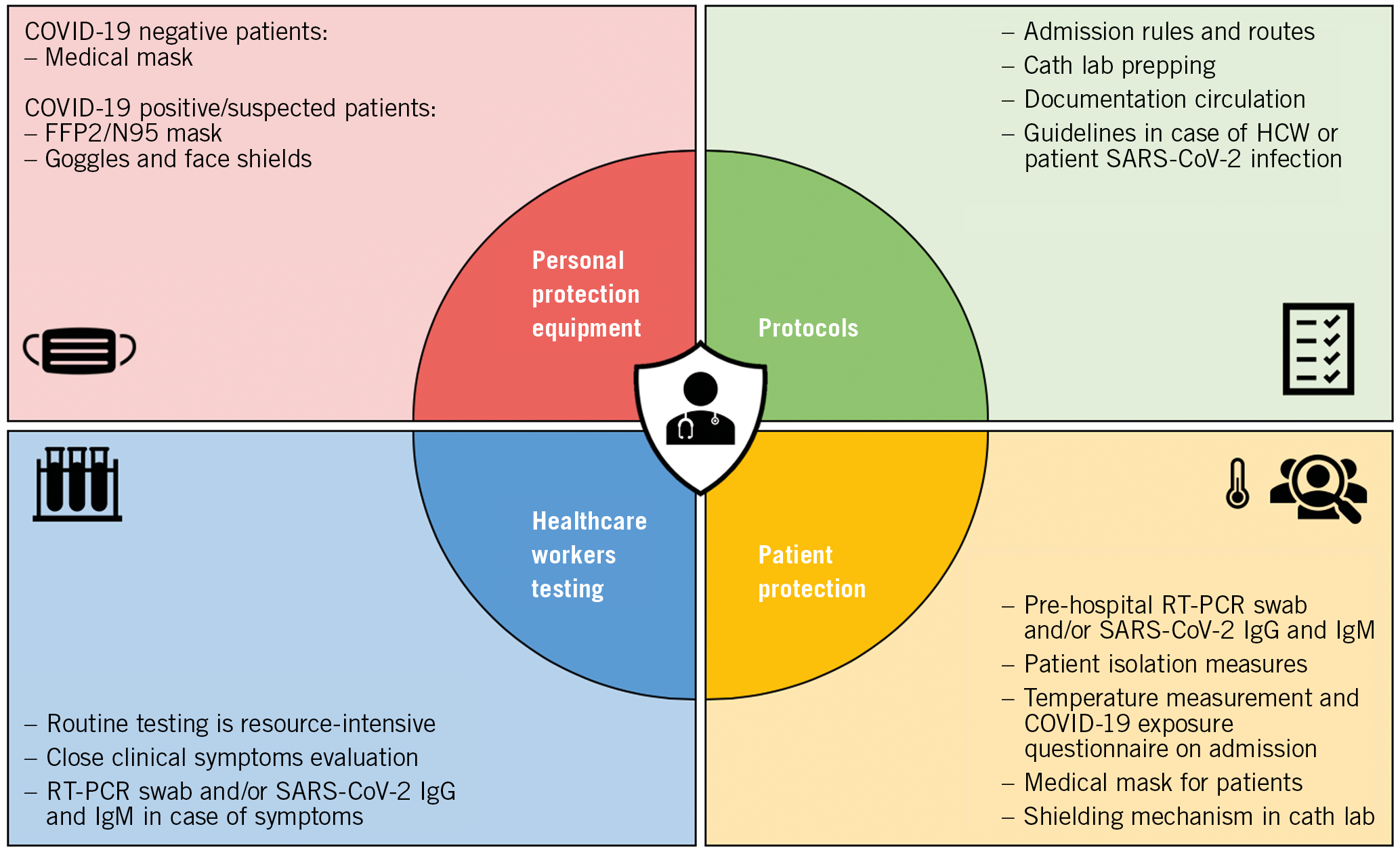

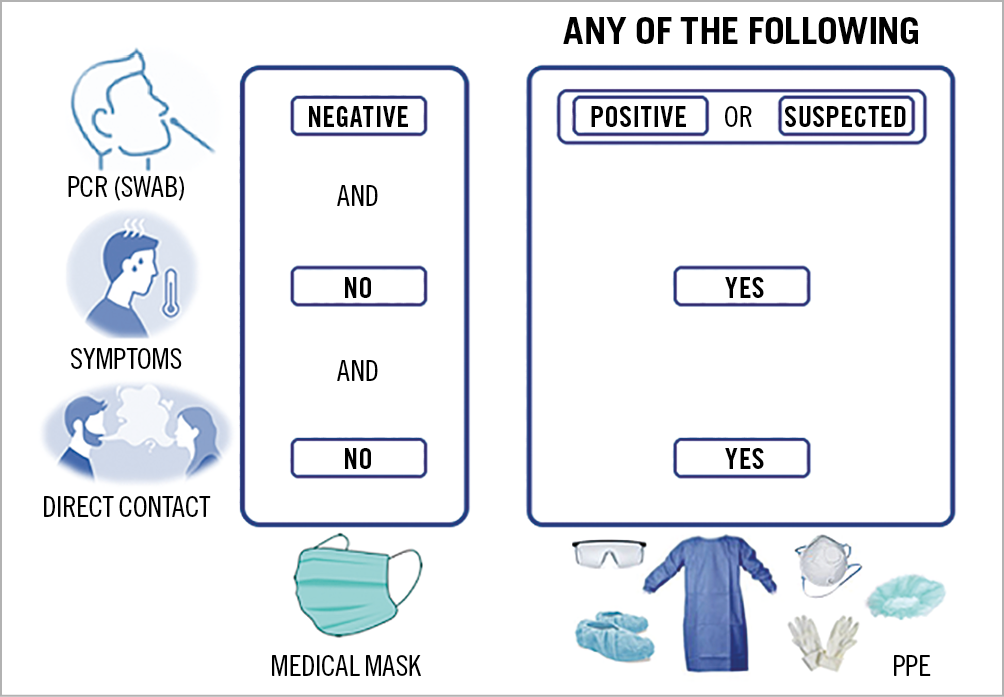

Depending on the local testing capacity and intensity of transmission in the area, healthcare facilities may test surgical patients for COVID-19 before the surgical procedure, regardless of risk assessment for COVID-1916 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. How to guarantee the safety of patients and healthcare workers.

Pre-hospital testing should always be conducted when the patient has symptoms suggestive of SARS-CoV-2 infection and should be considered in case of aerosol generating procedures (AGPs).

When pre-hospital testing is necessary, a period of (self-) isolation has to be taken into consideration according to local practice (i.e., home, hospital). However, other possible scenarios might occur, reflecting different regional and local practices.

In all cases, testing should be paralleled by a thorough collection of epidemiological history, evaluating the occurrence of symptoms of infection in the weeks preceding hospitalisation and the potential contact with an infected patient.

It also seems reasonable that patients wear medical masks during invasive cardiac procedures. This strategy seems reasonable because of the long virus incubation period and viral transmission by asymptomatic or early symptomatic patients17,18.

All other standard practices including accurate hand hygiene, physical distancing whenever possible, and systematic surface and zone disinfection are also essential to ensure both patient and HCW safety19.

MANAGEMENT OF OUTPATIENT VISITS

Supplementary Table 1 lists precautions for the management of outpatient visits.

For outpatient care, it seems sufficient to investigate symptoms of infection and contacts with infected patients using a questionnaire at the time of phone contact to arrange the date of the visit. It is advisable that patients wear a medical mask during this outpatient visit. However, there should be a strong emphasis on hand hygiene, respiratory hygiene and medical masks to be used by all patients with respiratory symptoms.

In addition, patient visits should be appropriately scheduled to avoid overcrowded waiting rooms, and disabled patients should be assisted by only one person.

Furthermore, for the safety of patients and HCWs, in each clinical scenario presented above, the number of HCWs involved in patient care should be limited to the minimum necessary.

Alternatives to face-to-face outpatient visits should use telemedicine (e.g., telephone consultations or cell phone videoconference) to provide clinical support without direct contact with the patient.

SARS-CoV-2 SWAB AND SEROLOGY TESTS

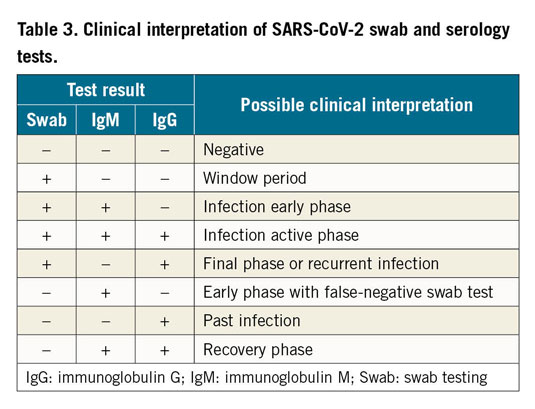

Clinical interpretation of SARS-CoV-2 swab and serology tests is described in Table 3.

Molecular assays for detection of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA using polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based techniques or nucleic acid hybridisation strategies can be used to identify SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals during the acute phase of the infection. It is, however, reported that an improperly taken swab may be the cause of a false negative result20. Based on the available studies, a sensitivity of 70% appears to be a reasonable estimate16. Evaluation of the pre-test probability based on a patient’s epidemiological status and perhaps repeated tests could overcome an individual test’s limited sensitivity. The sensitivity in asymptomatic individuals is not well established21.

A second category includes serological and immunological assays which detect antibodies after exposure to the virus. The detection of specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies is possible at the earliest about 10 days after the first clinical symptoms of infection, while immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies can be detected even later. The sensitivity of immunoassays may vary from 88.1 up to even 100% depending on the type of test22,23.

An overview of immunoassays and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) diagnostic kits for SARS-CoV-2 is provided in Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3.

More recently, rapid antigen detection (RAD) tests for qualitative determination of SARS-CoV-2 antigen also became available (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/antigen-detection-in-the-diagnosis-of-sars-cov-2infection-using-rapid-immunoassays). The trade-off is a highly variable sensitivity compared to RT-PCR (ranging from 0-94%), but specificity is consistently reported to be high (>97%). RAD tests are most likely to perform well in patients with high viral loads, as in the pre-symptomatic and early symptomatic phases of the illness, and in populations with expected high prevalence of disease (such as HCWs). However, a negative result cannot completely exclude COVID-19 infection, and therefore in symptomatic patients it might be suggested to repeat testing or preferably conduct confirmatory RT-PCR testing.

It is advisable, if local conditions permit, to maintain swab testing of all patients with real-time RT-PCR-based diagnostic kits detecting SARS-CoV RNA. Nevertheless, which strategy to use will depend on regional and local availabilities and protocols.

ENSURE HCW SAFETY

The safety of HCWs is one of the fundamental aspects of guaranteeing elective invasive procedures during different phases of the pandemic in order to ensure continuity of care to patients with cardiovascular disease. Data from the EAPCI survey show a drastic drop in cardiac procedures and the necessity to improve HCW safety24 and restore confidence amongst HCWs25,26,27. Reports from China and the Hubei region have reported infection rates in HCWs as high as 5.7% which has decreased over time to 2.7% with the use of appropriate protocols, increasing availability of PPE and widespread testing27. However, these rates were observed in front-line HCWs exposed to COVID-19 positive patients. In the elective cardiovascular patient setting, lower numbers are expected. Further studies to report the actual infection rate with routine elective testing are required.

The measures to guarantee HCW safety are illustrated in Figure 4 and Figure 5. PPE plays a crucial role in safe restoration of elective PCI procedures. In the early stage of the pandemic a shortage of such resources was reported, particularly the lack of FFP2/N95 masks and facial protective shields28. However, in patients where COVID-19 is confirmed or suspected, each operator should be equipped with FFP2/N95, eye protection (i.e., face shield or goggles), gloves and gowns, as previously described1,16. Indeed, medical masks might be sufficient when dealing with COVID-19 negative patients and airborne PPE only during AGPs.

Figure 5. PPE use according to different clinical scenarios.

Institutional protocols focusing on elective patient admission should be based on local epidemic status and local infrastructure to minimise the risk of admission of an infected patient. However, there are situations in which the maximum level of protection should be maintained (Figure 5).

Testing of HCWs is a resource-intensive measure. Its potential benefit needs to be carefully discussed and will largely depend on the extent of the pandemic and the local situation. In most cases, close attention to clinical symptoms, and routine masking of patients and staff can be more easily and reasonably implemented.

KEY MESSAGES

1. Strategies to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection should be tailored to the extent and phase of the pandemic of individual regions.

2. Pre-hospital triage is strongly suggested with clear pathways for “hot” and “cold” patients.

3. Depending on the local testing capacity and intensity of transmission in the area, healthcare facilities may test surgical patients for SARS-CoV-2 infection before the invasive cardiac procedure, regardless of risk assessment for COVID-19.

4. Pre-hospital testing should always be conducted in case of symptoms suggestive of SARS-CoV-2 infection and should be considered in case of AGPs.

5. Patients should wear medical masks during cardiac interventions and outpatient care visits.

6. For HCWs’ PPE, in case of confirmed or suspected COVID-19 positive patients, FFP2/N95 masks are indicated. In case of COVID-19 negative tested patients, medical masks might be sufficient.

7. Regarding testing of HCWs, in most cases close attention to clinical symptoms, and routine masking of patients and staff can be more easily and reasonably implemented.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has been associated with a significant decline of elective cardiac procedures to unload HCWs and ICUs but also with an unexpected reduction of primary PCI procedures, with an unusual surge of mechanical complications of STEMI. Elective cardiovascular interventions are now being restored in most regions, though at a different pace depending on the local epidemiology of the pandemic; some countries are already experiencing a second wave or new waves of infections. Recovery plans for elective invasive procedures should consider the interplay between the pandemic stage, the availability of healthcare resources and the priority of specific cardiac disorders. All waiting list patients should be re-prioritised according to clinical criteria (severity of symptoms and disease) with a recurring re-evaluation if necessary (telehealth/outpatient consultation). The decision as to which patient and procedure to prioritise depends on the expected benefit from the procedure, the degree of urgency required and the available resources. Strategies to prevent infection should be tailored on the degree of involvement in the pandemic of individual regions. However, pre-hospital triage is strongly suggested, and clear pathways for “hot” or presumed “hot” patients and “cold” patients are mandatory in each hospital. Depending on the local testing capacity and intensity of transmission in the area, healthcare facilities may test patients for SARS-CoV-2 infection before the surgical procedure, regardless of risk assessment for COVID-19. Pre-hospital testing should always be conducted in case of symptoms suggestive of SARS-CoV-2 infection and should be considered in case of AGPs. The use of a medical mask during procedures performed in patients with recent negative testing and without symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 disease would be appropriate. The use of dedicated PPE is indeed advisable before, during, and after procedures performed in elective patients with confirmed and suspected COVID-19 infection.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the help of Alessandro Beneduce, MD and Francesca Ziviello, MD in manuscript preparation.

Conflict of interest statement

A. Chieffo declares lecture/consultant fees from Abbott Vascular, Abiomed, Cardinal Health, Biosensors, and Magenta. G. Tarantini declares speaker fees from Edwards Lifesciences, Boston Scientific, and Neovasc Inc. M. Roffi declares institutional research grants from Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Terumo, Biotronik, and GE Healthcare. G. Stefanini declares a research grant from Boston Scientific and speaker fees from Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Biosensors, and B. Braun. P. Buzman declares speaker fees from Novartis and unrestricted research grants from Meril Lifesciences. R. Moreno declares speaker and consultant fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Biosensors, Biotronik, Daiichi Sankyo, Edwards Lifesciences, Ferrer, Medtronic, Terumo, Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, and New Vascular Therapy. G. Cayla declares personal fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Medtronic, MSD, Pfizer, and Sanofi. A. Baumbach declares institutional research support from Abbott Vascular, and consultation and speaker fees from Abbott Vascular, AstraZeneca, Cardinal Health, Sinomed, MicroPort, KSH, and Medtronic. H. Nef declares speaker fees from Boston Scientific, Abbott, AstraZeneca, Shockwave, SMT and Siemens, consultant fees from Boston Scientific and an institutional grant from SMT. J. Mauri Ferre declares lecture fees from Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Cardiva 2 SL and Medtronic, and consultant fees from Biosensors. M. Voskuil declares institutional research grants from Medtronic, Edwards and Boston Scientific. S. Windecker declares research and educational grants to the institution from Abbott, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Bayer, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Cardinal Health, Cardiovalve, CSL Behring, Daiichi Sankyo, Edwards, Johnson and Johnson, Medtronic, Medalliance, Guerbet, Polares, Sanofi, Terumo, V-Wave and Xeltis. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.