Abstract

Aims: Bioresorbable scaffolds are increasingly used in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. ABSORB EXTEND is an ongoing study that will recruit 800 patients. This report evaluates acute and late scaffold failure in the first 450 patients enrolled in ABSORB EXTEND who have completed 12 months follow-up.

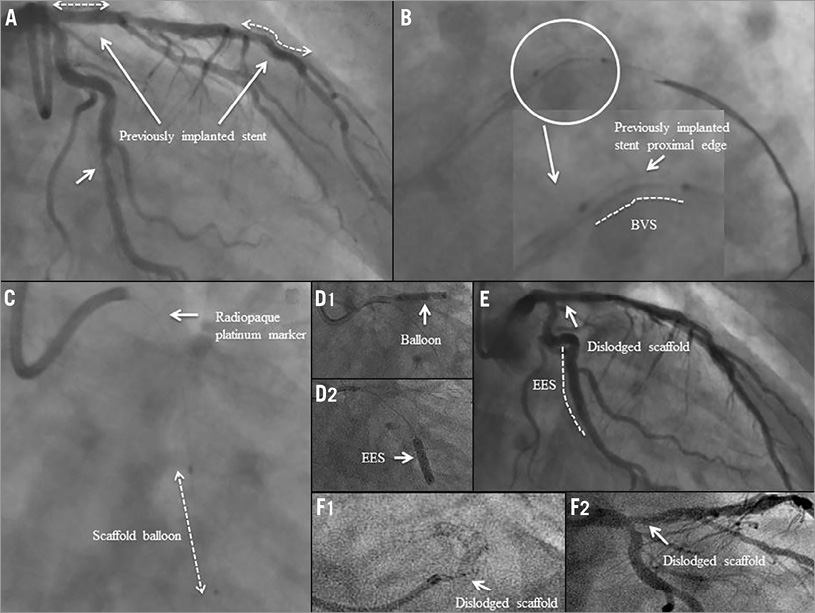

Methods and results: Clinical event data from the first 450 patients enrolled in ABSORB EXTEND have demonstrated low rates of ischaemia-driven MACE (4.2%) and target vessel failure (4.7%) at 12 months. There have been seven cases of device failure in this study: three cases of scaffold dislodgement (0.67%) and four cases of subacute or late scaffold thrombosis (0.89%). All scaffold dislodgements occurred in the left circumflex (LCX), and in two cases dislodgement was observed after reinsertion of the same device. Two cases of subacute scaffold thrombosis and two late scaffold thromboses were observed. Two out of four cases of scaffold thrombosis seemed to be related to either premature discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) or resistance to clopidogrel.

Conclusions: This is the first report specifically describing the incidence and the potential mechanisms of scaffold dislodgement and scaffold thrombosis as seen in the ABSORB EXTEND trial.

Introduction

Acute vessel closure, due to dislodgement of a coronary stent during deployment or an early stent thrombosis, is a rare but potentially fatal complication of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)1. Late or very late thrombosis also remains a long-term concern with metallic drug-eluting stents, due to delayed healing potentially caused by the permanent presence of foreign bodies such as metals and coating materials1-4.

The Absorb everolimus-eluting poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) bioresorbable vascular scaffold system (BVS; Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) is a novel approach to treat coronary lesions5-8. After complete bioresorption of the polymeric struts8, the risk of very late scaffold thrombosis may theoretically be reduced due to the absence of foreign material9,10. On the other hand, the thick polymeric struts (total strut thickness=156 μm) crimped onto the delivery balloon contribute to the large profile of the device that may cause friction between the device and the diseased vessel wall or any daughter catheter, resulting in dislodgement of the scaffold10. Until now, however, there have been no specific reports of these acute and late complications with the Absorb BVS beyond anecdotal presentations of isolated cases.

ABSORB EXTEND (unique identifier NCT01023789) is an international prospective, single-arm study that will recruit 800 patients with long lesions (length up to 28 mm) or lesions in small vessels (2.0-3.8 mm diameter). Treatment of two de novo native coronary artery lesions is also permitted when each lesion is located in a different epicardial vessel. The details of the trial are described in the previous report11.

The first 450 patients enrolled in ABSORB EXTEND have completed 12 months follow-up and this interim report presents seven cases of device failure detected in this population. Three cases of scaffold dislodgement (0.67%) and four cases of subacute or late scaffold thrombosis (0.89%) are described in detail to evaluate the underlying mechanisms and to make some practical recommendations to avoid these serious complications.

Case descriptions

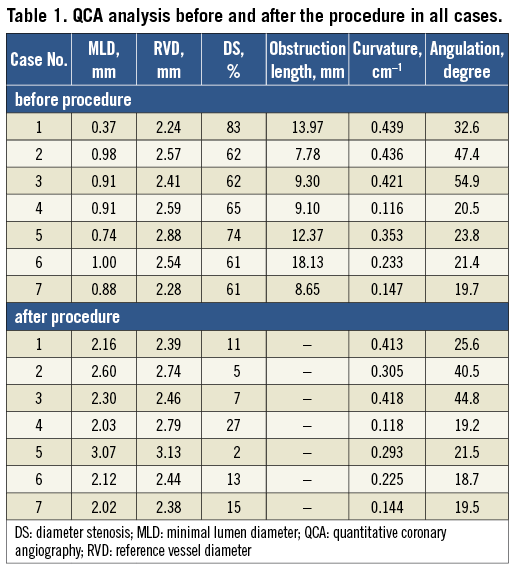

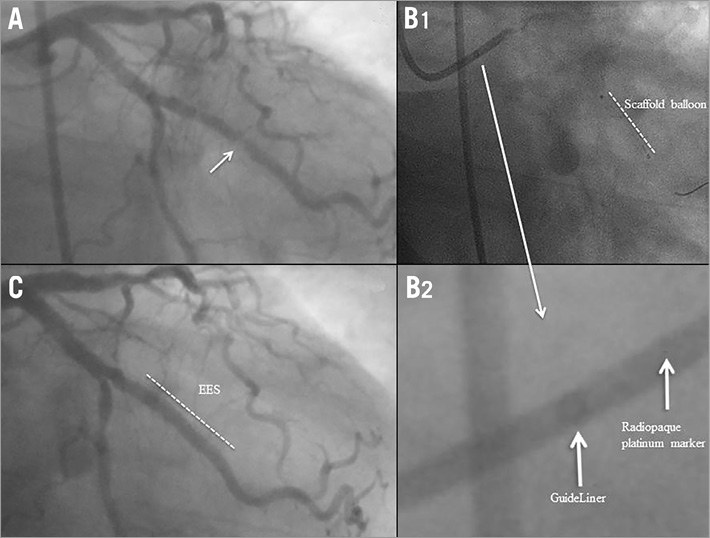

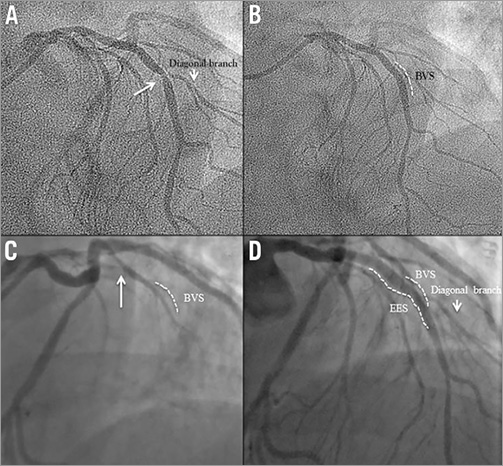

CASE 1. SCAFFOLD DISLODGEMENT SUBSEQUENTLY CRUSHED BY METALLIC STENTS

In a 74-year-old man coronary angiography showed a severe lesion with a percentage diameter stenosis (DS) of 83% (Table 1) in the mid segment of a calcified left circumflex (LCX) coronary artery (Figure 1A). After the first predilatation with a 2.5×15 mm balloon, a 3.0×18 mm Absorb BVS failed to cross the tortuous proximal LCX. After the second dilatation, the same Absorb scaffold was reinserted (time between the first and second insertion of the scaffold is unknown). However, the same Absorb scaffold still failed to cross and unexpectedly dislodged from the balloon at a site of fluoroscopic calcification proximal to the lesion when the device was pushed forward (Figure 1B, Figure 1C). Two 3.0×18 mm metallic everolimus-eluting metallic stents (EES) were deployed in an overlapping fashion to crush the dislodged scaffold against the vessel wall, and an additional 3.0×18 mm EES was deployed at the target lesion (Figure 1D). The follow-up was uneventful during 12 months.

Figure 1. Case 1. A) Coronary angiography showing a severe lesion in the mid segment of a calcified left circumflex (LCX) coronary artery. B) & C) The same Absorb scaffold still failed to cross and unexpectedly dislodged. D) Two metallic everolimus-eluting metallic stents (EES) were deployed in an overlapping fashion to crush the dislodged scaffold against the vessel wall, and an additional EES was deployed at the target lesion.

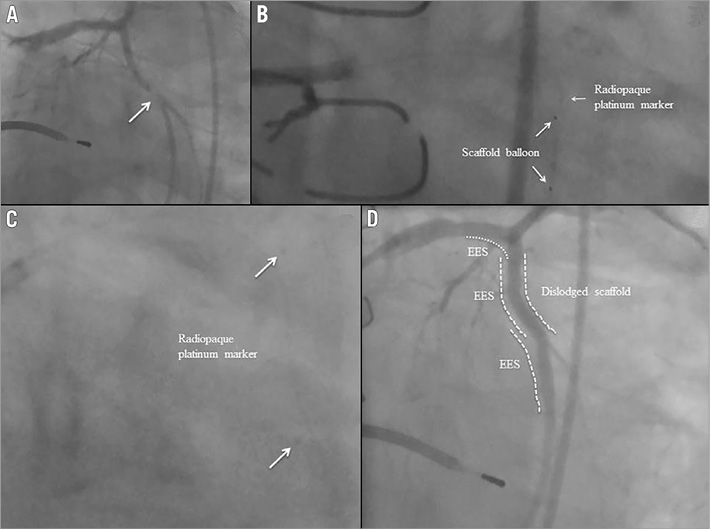

CASE 2. A DISLODGED SCAFFOLD LEFT INSIDE A PREVIOUSLY IMPLANTED METALLIC STENT

In a 60-year-old man diagnostic coronary angiography showed a moderate stenosis (Table 1) in the mid segment of a highly tortuous LCX. Two metallic stents had previously been implanted in the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) and it seemed that the proximal stent had partially jailed the ostium of the LCX (Figure 2A). After predilation using a 2.5×15 mm balloon, a 3.0×18 mm Absorb BVS was advanced beyond the ostium of the LCX, but it failed to progress into the proximal LCX despite the use of an extra support guidewire (Figure 2B). While the Absorb BVS delivery system and extra support guidewire were being withdrawn, the Absorb scaffold unexpectedly dislodged from the balloon and became positioned with its distal edge in the proximal LCX and its proximal edge in the LMS (Figure 2C). An attempt to retrieve the dislodged scaffold was made with a GooseNeck® snare (ev3 Inc., Plymouth, MN, USA). However, it failed as the dislodged scaffold was inadvertently pushed into the metallic stent located in the proximal LAD. Following this, another guidewire was inserted into the LAD and a second attempt was made to retrieve the dislodged scaffold using the GooseNeck snare, but it failed again. A balloon was then inflated to crush the dislodged scaffold in the proximal LAD and finally an EES was successfully deployed at the target lesion (Figure 2D, Figure 2E). Five months later, coronary angiography revealed a severe stenosis in the proximal LAD and proximal LCX (Figure 2F), and the patient was referred for surgical treatment.

Figure 2. Case 2. A) Coronary angiography showing a moderate stenosis in the mid segment of a highly tortuous LCX. Two metallic stents had previously been implanted in the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) and it seemed that the proximal stent had partially jailed the ostium of the LCX. B) An Absorb BVS was advanced beyond the ostium of the LCX, but it failed to progress. C) The Absorb scaffold unexpectedly dislodged and became positioned with its distal edge in the proximal LCX and its proximal edge in the left main stem (LMS). D1) A balloon was then inflated to crush the dislodged scaffold in the proximal LAD. D2) An EES was successfully deployed at the target lesion. E) Final result. F1) & F2) Five months later, coronary angiography revealed a severe stenosis in the proximal LAD and LCX.

CASE 3. SCAFFOLD DISLODGEMENT DUE TO A TORTUOUS VESSEL

A 61-year-old male underwent coronary angiography which showed a moderate stenosis (Table 1) in the mid segment of a calcified LCX (Figure 3A). After the first predilatation with a 2.5×15 mm balloon, a 3.0×18 mm Absorb BVS failed to cross the lesion. After two additional predilatations with a 3.0×15 mm balloon, the same Absorb BVS system was reinserted, but it was unable to pass a moderate bend in the LCX proximal to the predilated lesion. Another attempt was made to deliver the scaffold using a GuideLiner™ catheter (Vascular Solutions Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) and the scaffold delivery system was apparently positioned at the target lesion (Figure 3B1). However, after balloon inflation, the radiopaque markers at the edges of the scaffold were not visible on fluoroscopy (Figure 3B1, Figure 3B2). When the GuideLiner™, guidewire and the Absorb BVS delivery system were removed together as a single unit, the dislodged scaffold was found to be inside the GuideLiner™. Following this, a 2.75×18 mm EES was successfully deployed at the target lesion without any further procedural complications (Figure 3C). The patient had an uneventful clinical course and was discharged two days after the procedure. Approximately three months after the procedure, the patient passed away at home (unwitnessed sudden death). This event was adjudicated as a possible stent thrombosis by the clinical events committee of the ABSORB EXTEND trial.

Figure 3. Case 3. A) Coronary angiography showing a moderate stenosis in the mid segment of a calcified LCX. B1) The scaffold delivery system was apparently positioned at the target lesion. B2) When the GuideLiner™ system was removed together as a single unit, the dislodged scaffold was found to be inside the GuideLiner™. C) An EES was successfully deployed at the target lesion.

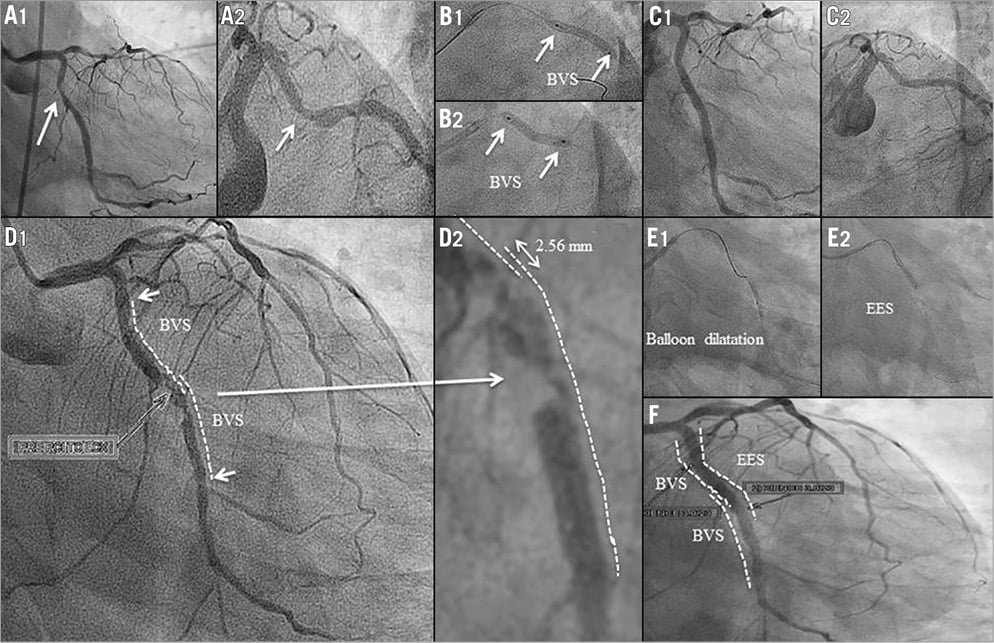

CASE 4. SUBACUTE SCAFFOLD THROMBOSIS AT THE SITE OF OVERLAPPING SCAFFOLDS

In a 56-year-old man coronary angiography showed a moderate stenosis (Table 1) in the proximal segment of the LCX (Figure 4A1, Figure 4A2). After predilatation, a 3.0×28 mm Absorb scaffold failed to be delivered. Two additional predilatations were performed and the same Absorb BVS system was reinserted over an extra support guidewire (ASAHI GRAND SLAM™; Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA), but was unable to cross. A proximal scaffold deformation was observed (post-withdrawal observation) after having retracted the Absorb BVS system and the guidewire. Following this, two 3.0×18 mm Absorb BVS were successfully deployed (Figure 4B, Figure 4C). The distance between the scaffold radiopaque markers in the overlapping segment was 2.56 mm as measured by QCA.

Figure 4. Case 4. A1) & A2) Coronary angiography showing a moderate stenosis in the proximal segment of the LCX. B1) & B2) Two Absorb BVS were successfully deployed. C1) & C2) Final results. D1) & D2) Angiography on day seven revealed a thrombotic lesion at the site of the overlapping scaffolds in the mid segment of the LCX. E1), E2) & F) An EES was successfully implanted to cover the lesion and the overlapping segment.

Six days after the procedure the patient presented with a non-STEMI and was treated with thrombolytic therapy. Angiography on day seven revealed a thrombotic lesion at the site of the overlapping scaffolds in the mid segment of the LCX (Figure 4D1, Figure 4D2). The patient claimed to be fully compliant with dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT). An EES was successfully implanted to cover the lesion and the overlapping segment of the scaffolds (Figure 4E, Figure 4F).

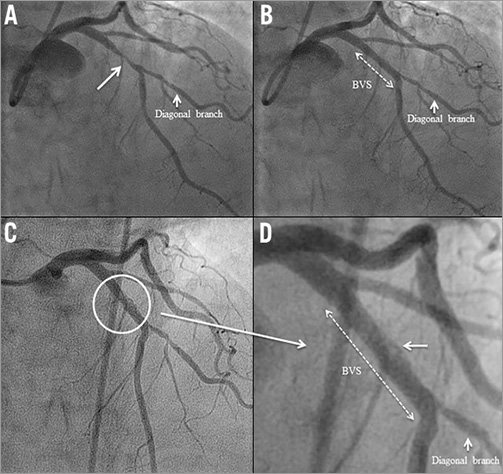

CASE 5. SUBACUTE SCAFFOLD THROMBOSIS OCCURRING TWO DAYS AFTER DISCONTINUATION OF DAPT

A 58-year-old woman underwent PCI with a 3.0×18 mm Absorb BVS in the mid segment of the LAD (Figure 5A, Figure 5B). On day 27, the patient stopped taking both aspirin and clopidogrel. Two days after DAPT discontinuation, she presented with a non-STEMI and was treated by thrombolysis. On day 32, coronary angiography showed a patent LAD with haziness (Figure 5C, Figure 5D). DAPT was restarted and follow-up was uneventful.

Figure 5. Case 5. A) Coronary angiography showing a moderate stenosis in the proximal segment of the LAD. B) An Absorb BVS was successfully deployed at the target lesion. C) & D) On day 32, coronary angiography showed a patent LAD with haziness.

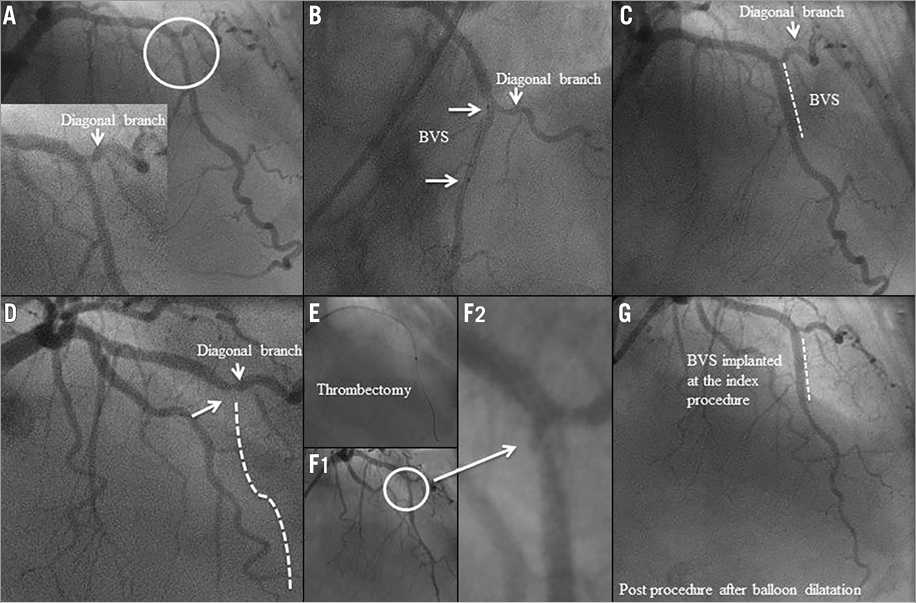

CASE 6. LATE SCAFFOLD THROMBOSIS IN A PATIENT WITH RESISTANCE TO CLOPIDOGREL

An 80-year-old woman underwent PCI with a 3.0×18 mm Absorb BVS for a moderate stenosis (Table 1) in the mid segment of the LAD (Figure 6A-Figure 6C).

Figure 6 Case 6. A) Coronary angiography showing a moderate stenosis in the mid segment of the LAD. B) & C) An Absorb BVS was successfully deployed at the target lesion. D) Coronary angiography showed complete thrombotic occlusion of the LAD. E) Primary PCI with a manual thrombectomy was performed. F1) & F2) Coronary angiography showed a patent LAD with haziness after thrombectomy. G) Coronary angiography showed a patent LAD without haziness after balloon dilatation.

Seventy-five days after the index procedure, she presented with an acute anterior STEMI. Coronary angiography showed complete thrombotic occlusion of the LAD proximal to the scaffold up to the take-off of a diagonal branch (Figure 6D). Primary PCI with a manual thrombectomy and a balloon dilatation was successfully performed (Figure 6E-Figure 6G). At the time of the emergency procedure, the patient reported that she was scrupulously taking her DAPT. However, the platelet aggregation test indicated that she was either not on DAPT or resistant to clopidogrel, since her ADP-induced aggregation of platelets was normal. The patient claimed to be fully compliant with DAPT and hence a higher dose of clopidogrel (150 mg daily) was prescribed to prevent further scaffold thrombosis. The follow-up was uneventful.

CASE 7. LATE SCAFFOLD THROMBOSIS OF UNKNOWN CAUSE

A 56-year-old man with dyslipidaemia, a family history of coronary artery disease (CAD) and angina class II underwent PCI with a 3.0×18 mm Absorb BVS in the mid segment of the LAD (Figure 7A, Figure 7B). After Absorb BVS implantation, post-dilation was performed with a 3.0×9.0 mm balloon (non-compliant balloon) at maximal pressure of 16 atm (rated balloon pressure: 18 atm).

Figure 7. Case 7. A) Coronary angiography showing a moderate stenosis in the mid segment of the LAD. B) An Absorb BVS was successfully deployed at the target lesion. C) At day 239, coronary angiography revealed a total occlusion of the LAD, proximal to the preciously implanted Absorb scaffold. D) Following manual thrombectomy, an EES was successfully deployed.

At day 239, following a bee sting, he presented with an acute anterior STEMI. The patient was still on DAPT at that time. Urgent coronary angiography revealed total occlusion of the LAD, proximal to the previously implanted Absorb scaffold (Figure 7C). Following manual thrombectomy, an EES was successfully deployed (Figure 7D).

Discussion

The main findings of the current report are the following: 1) in the first 450 patients enrolled in the ABSORB EXTEND trial, scaffold dislodgement occurred in three cases; 2) all dislodgements occurred in the LCX, and in two cases dislodgement was observed after reinsertion of the same device; 3) two subacute scaffold thromboses and two late scaffold thromboses were observed; 4) two scaffold thromboses seemed to be related to either premature discontinuation of DAPT or resistance to clopidogrel.

SCAFFOLD DISLODGEMENT

Dislodgement of a metallic stent from the delivery balloon during deployment is a rare complication, reported in 0.32-1.2% of procedures in the early 2000s12. Metallic stent dislodgement from the delivery system occurs most often when the stent balloon device is pulled back into the guiding catheter, because the target lesion cannot be either reached or crossed despite a forceful pushing manoeuvre13-15. Risk factors for stent dislodgement include severe coronary angulations, coronary tortuosity, diffuse long lesions and calcified lesions. In addition, stent dislodgement has been reported to be the highest in the LMS or LAD16.

In the current series which included relatively simple lesions (mean lesion length: 11.6 mm, type B2/C lesions according to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association: 38.6%, calcification: 13.2%), scaffold dislodgement was observed in 0.67% (3/450). All cases of dislodgement occurred in the LCX (mean baseline vessel angulation: 45.0 degrees; mean baseline vessel curvature: 0.432 cm–1). One scaffold was dislodged when the crimped scaffold was retracted after the delivery failure of the device, one was dislodged from the balloon when the device was advanced through a 6 Fr daughter catheter, and one was observed after crossing the ostium of the LCX jailed by a metallic stent previously implanted in the LAD. Of these three cases, two scaffold dislodgements occurred when the same scaffolds were reinserted after failed delivery attempts.

The Absorb BVS has a crossing profile of 1.4 mm with a strut thickness of 156 μm, and consists of in-phase zigzag hoops linked by straight bridges17. Alternative processing techniques have been developed to enhance polymeric scaffold retention, and bench-top testing indicates retention forces equivalent to those observed with metallic stents. However, these thick polymeric struts with a large crossing profile may contribute to friction between the device and a tortuous/calcified vessel or a daughter catheter, resulting in device dislodgement when forcefully pushing the scaffold10. In case 3, a 6 Fr GuideLiner™ with a 6 Fr guiding catheter was used, which was not compatible with the current version of the Absorb scaffold. Usage of the 6 Fr GuideLiner™ system should be avoided.

The risk of scaffold dislodgement may increase with the combination of several factors, including tortuous and calcified vessels proximal to the target lesion, prolonged exposure to moisture during repeated removal and reinsertion of a scaffold, and friction against a tightly fitting delivery catheter (such as the GuideLiner™) where enough dimensional clearance for the scaffold is not assured. To prevent scaffold dislodgement, it is recommended to avoid prolonged contact with moisture in the setting of repeated removal and reinsertion of the same device after a failed delivery. It would be advisable to use a new scaffold in such a situation. In the case of heavily calcified lesions, optimal lesion preparation using cutting/scoring balloons or rotational atherectomy should be considered before implantation of the Absorb BVS.

If dislodgement of a device occurs, prompt recognition and an attempt at percutaneous retrieval using a snare system or a multi-wire technique is advisable. If the retrieval manoeuvres are not technically feasible or fail, the dislodged scaffold could be crushed against the arterial wall by implantation of a metallic stent. In this case, however, the operator should be aware that the crushed polymeric scaffold will result in a circular and non-laminated structure as seen with crushed metallic stents.

SCAFFOLD THROMBOSIS

Metallic stent thrombosis is multifactorial, including procedure-related factors such as underexpansion, multiple stent use, dissections, and late acquired stent malapposition due to resolution of thrombus on the vessel wall or abnormal vessel healing1-4,18.

In the current series, two subacute and two late scaffold thromboses were observed (0.89%). Acutely after implantation, PLLA polymer is, at least in vitro, somewhat less thrombogenic than a metal without a coating19. In the blood flow, however, the presence of thick struts creates alteration of shear stress, resulting in high shear stress on top of the strut and low shear stress behind the strut which may trigger platelet aggregation20. Preclinical reports have demonstrated that metallic stents with the thinner struts are less thrombogenic21,22. During the acute/subacute phase after implantation of an Absorb scaffold, efficient platelet inhibition is mandatory22. The optimal duration of DAPT after implantation of Absorb scaffolds has not been investigated. In a porcine coronary angioplasty model, the polymeric struts were associated with lesser granuloma formation than the first-generation sirolimus-eluting stents, suggesting that the bioresorption process does not provoke any significant inflammation. In the ABSORB Cohort B trial, tissue coverage as assessed by optical coherence tomography (OCT) was almost complete (97%) at six months5. The optimal duration of DAPT after implantation of Absorb scaffolds has not been investigated. The protocols of previous ABSORB trials mandated at least six months of DAPT. It is noteworthy that the mean duration of DAPT was 403 days in the ABSORB Cohort B trial5. Given the paucity of data, the optimal duration of DAPT should be prospectively assessed in future studies.

In the present series, late scaffold thrombosis occurred in one case with overlapping Absorb scaffolds. In a juvenile porcine model, the overlapping Absorb scaffolds showed delayed healing and slower tissue coverage than in non-overlapping scaffolds23: the coverage of the overlapping segment was 80.1% and 99.5% at 28 and 90 days after implantation, respectively, suggesting that complete coverage in humans may take up to 18 months4. In case of overlapping scaffolds, a relatively longer duration of DAPT with more potent agents (e.g., ticagrelor or prasugrel) could be considered.

One late scaffold thrombosis occurred following a bee sting. The mechanism responsible for STEMI in this patient could have been coronary artery spasm (partly mediated by psychological stress related to the intensity of the anaphylactic reaction) with thrombosis secondary to cardiovascular collapse24. However, the precise mechanism of scaffold thrombosis in this case remains uncertain.

Conclusion

This is the first report specifically describing the incidence and the potential mechanisms of scaffold dislodgement and scaffold thrombosis seen in the ABSORB EXTEND trial. To avoid scaffold dislodgement, appropriate lesion preparation is mandatory. In case of unsuccessful initial delivery, a second insertion of the same scaffold should be avoided. Adherence to antiplatelet therapy is of paramount importance to avoid acute or subacute scaffold thrombosis.

| Impact on daily practice Bioresorbable scaffolds are increasingly used in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions; however, the early clinical experiences in the ABSORB EXTEND trial (n=450) demonstrated scaffold dislodgement in 0.67% and scaffold thrombosis in 0.89% of cases. To avoid scaffold dislodgement, appropriate lesion preparation is mandatory and a second insertion of the same scaffold should be avoided. Adherence to the antiplatelet therapy is of paramount importance to avoid acute or subacute scaffold thrombosis. |

Guest Editor

This paper was guest edited by Antonio Colombo, MD, S. Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. The Guest Editor has no conflicts of interest to declare.