Abstract

Left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) is a first-line therapy for stroke prevention in patients suffering from atrial fibrillation (AF). While patients at high risk for bleeding or patients with previous bleeding have the highest relative risk reduction from LAAO, it is the younger patients with a high lifetime bleeding risk who benefit from the highest absolute risk reduction after LAAO. Therefore, LAAO should be discussed with every AF patient, as an alternative to lifelong oral anticoagulation. The patient needs to be informed about the risks and benefits of each treatment strategy in order to take an informed treatment decision.

Introduction

In 2009, the results from the Percutaneous closure of the left atrial appendage versus warfarin therapy for prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomized non-inferiority trial (PROTECT-AF) were first published1. The study proved the concept of left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO); however, procedural adverse safety events disguised the overall benefit of the procedure. After one year of follow-up, LAAO was non-inferior to warfarin with regard to the primary endpoint of stroke, cardiovascular death and systemic embolism (LAAO vs. warfarin 3.0 events/100 patient-years vs. 4.9 events/100 patient-years, RR 0.62, 95% CI: 0.35-1.25). In 2014, after 3.8 years of follow-up, significantly more adverse events occurred in the warfarin group. This resulted in superiority of LAAO regarding the primary endpoint (8.4% vs. 13.9%, HR 0.61, 95% CI: 0.38-0.97; p=0.04), as well as in the single endpoints of cardiovascular (3.7% vs 9%, HR 0.4, 95% CI: 0.21-0.75; p=0.005) and all-cause mortality (12.3% vs. 18%, HR 0.66, 95% CI: 0.45-0.98; p=0.04)2. Besides data from randomised trials, the bulk of real-world evidence supports the findings3-10.

On the other hand, medical therapy for stroke prevention has also evolved over recent years, with randomised data on non-vitamin-K-dependent oral anticoagulants (NOACs) showing superiority over warfarin for reduction of stroke and systemic embolism11-14. Amongst the four landmark trials, only apixaban could show a significant all-cause mortality benefit over warfarin (all-cause death apixaban vs. warfarin: 3.52% vs. 3.94%, HR 0.89, 95% CI: 0.8-0.99; p=0.047).

While the NOAC trials had to include 14,000 to 21,000 patients with a follow-up of two years to show statistical superiority over warfarin, LAAO in the PROTECT-AF trial required only 700 patients with a follow-up of 3.8 years. The reason is a five times higher absolute risk reduction (ARR) with LAAO as compared to NOACs (ARR in PROTECT-AF: 1.45%/year; ARR in RELY: 0.08%/year with dabigatran 110 mg bid and 0.29%/year with dabigatran 150 mg bid).

While the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) acknowledged the favourable data on LAAO, and approved the WATCHMAN® device (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) in March 2015 for patients who have “an ‘appropriate reason’ to seek a non-drug alternative to warfarin”, the European Guidelines pitifully ignored the data and downgraded LAAO to a class IIb indication15. This contrasts with the European EHRA/EAPCI expert consensus from 2014 which states that LAAO should be discussed with the patients and LAAO should be considered in patients who refuse oral anticoagulation16.

With atrial fibrillation (AF) being epidemic in western countries, it goes without saying that stroke prevention is a huge market for the industry. This is even more true for NOACs than it is for LAAO, inherent to the fact that every physician, from family doctor, to general cardiologist, to surgeon (for thrombosis prophylaxis), can and should prescribe NOACs. On the other hand, LAAO is a wallflower, with the procedure only being performed by highly specialised physicians, such as interventional cardiologists and electrophysiologists. This illustrates a skewed balance; physicians should therefore be careful when interpreting guidelines, data, and recommendations.

The concept of LAAO can also be referred to as mechanical vaccination and should be discussed with every patient who suffers from AF as an alternative to NOACs, as suggested by the EHRA/EAPCI consensus statement.

Hereinafter, we will discuss everyday clinical scenarios. The readers can ask themselves if they would support LAAO in each situation. Indications for and thresholds to perform LAAO depend on experience, volume and skills of operators - this manuscript reflects the practice of experienced, high-volume operators from three large centres in Switzerland.

Scenarios

PATIENT 1

A 74-year-old hypertensive male in AF with moderate aortic stenosis was prescribed dabigatran 150 mg bid for stroke prophylaxis. He was admitted with melaena and anaemia with a haemoglobin of 7.4 g/l. Despite a thorough diagnostic work-up, no definite source of bleeding was identifiable and bleeding from angiodysplasia was considered a likely differential diagnosis.

What do you recommend for the patient? A: continue dabigatran, B: change to another NOAC, C: change to warfarin, or D: LAAO?

PATIENT 2

A 33-year-old farmer was admitted with a transient ischaemic attack (TIA). During stroke work-up, he was found to be in AF with a heart rate of 110/min, the most likely reason for his reduced ejection fraction of 38%. No atherosclerosis was found despite his being hypertensive. Besides AF, he was also found to have a large patent foramen ovale (PFO) with an atrial septum aneurysm. Thrombophilia testing was negative.

What do you recommend for this patient? A: warfarin, B: NOAC, C: LAAO, or D: LAAO and PFO occlusion?

If you opt for option C or D, what antiplatelet regimen would you choose?

PATIENT 3

An 82-year-old hypertensive lady in AF suffering from severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis, normal ejection fraction and previous chest radiation for breast cancer was slated to undergo transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI).

What do you recommend for this patient as antithrombotic therapy? A: warfarin, B: NOAC, or C: LAAO in addition to TAVI?

PATIENT 4

An underweight (BMI 18) 52-year-old lady in AF presented with an anterior ST-elevation myocardial infarction and was successfully treated with three drug-eluting stents. As an antithrombotic regimen, the patient continued her NOAC on a low dose (rivaroxaban 15 mg) and clopidogrel was added for one year. Her ejection fraction measured 28%, and therefore she was prescribed beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, spironolactone, and torasemide. As her ejection fraction did not improve after three months, she underwent ICD implantation.

What do you recommend for this patient for stroke prophylaxis? A: continue medication as initially intended, or B: perform LAAO, terminate NOAC the day of the procedure and prescribe the patient dual antiplatelet therapy for a maximum of one year, followed by acetylsalicylic acid indefinitely?

PATIENTS WITH PREVIOUS MAJOR BLEEDING (PATIENT 1)

Bleeding is not benign. While intracranial bleeding is recognised as a dangerous condition by most physicians, the mortality after gastrointestinal bleeding is often underestimated and the danger misjudged.

Patients with subdural haematoma have an in-hospital mortality rate of 8% and a five-year mortality rate of 35%. This is significantly worse than age-matched controls, with a hazard ratio for death of 3.52 and a 12.4-year reduction in life expectancy17. Outcome after intracerebral haemorrhage is even worse: after one year, more than half of all patients are dead (54%), and five-year survival was found to be only 29% in a large meta-analysis18.

Patient 1 suffered from a gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding without documented cause. According to a cohort study from the Netherlands, in-hospital mortality in such patients is as high as 10-20%19. The high in-hospital mortality after upper GI bleeding was confirmed in a large cohort study from the United Kingdom on >6,000 patients admitted with GI bleeding. In this study, overall in-hospital mortality was 10%20.

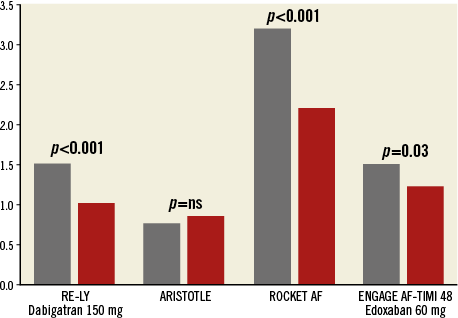

Management of these patients is challenging. Although intracranial bleeding and life-threatening bleeding are significantly reduced with NOACs as compared to warfarin, it seems that it is the GI tract that is particularly prone to bleeding under NOACs. In the ROCKET AF trial, major bleeding from a gastrointestinal site was 3.2% with rivaroxaban as compared to 2.2% with warfarin (p<0.001)12. In the RE-LY trial, major gastrointestinal bleeding occurred at a yearly rate of 1.5% if treated with dabigatran 150 mg bid, as compared to 1%/yr under warfarin (HR 1.36, 95% CI: 1.09-1.7, p=0.007)13 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Gastrointestinal bleeding with NOACs. Except for the ARISTOTLE trial, gastrointestinal bleeding was significantly more frequent with non-vitamin-K-dependant oral anticoagulants (NOACs, grey bars) as compared to warfarin (red bars). Expressed as annual bleeding rate, except for the ROCKET AF trial (expressed as number of events per 100 patient-years).

In patients at high risk for bleeding (e.g., as expressed by a high HAS-BLED score) or with relevant prior bleeding, LAAO may be the preferred treatment modality for stroke prevention. Since acetylsalicylic acid also increases the risk for peptic ulcers, proton pump inhibitors should preferably be prescribed in these patients, in case the patient has an indication for lifelong acetylsalicylic acid. Otherwise, antiplatelet therapy should preferably be terminated six months after LAAO in patients with diagnosed ulcers.

The post-procedural drug regimen after LAAO differs between centres and is often adapted to the individual patient’s risk of bleeding. A short course of oral anticoagulation (45 days), followed by clopidogrel for up to 180 days after LAAO, was prescribed in the PROTECT-AF trial, whereas many physicians immediately terminate oral anticoagulation and prescribe dual antiplatelet therapy for three to six months9. In patients at high risk for bleeding, even acetylsalicylic acid monotherapy21-24 or no antiplatelet therapy25 is a valuable option.

YOUNG PATIENTS AND PATIENTS WITH HIGH-RISK ACTIVITIES (PATIENT 2)

The 33-year-old farmer requires lifelong stroke prophylaxis. He has a low annual bleeding risk of 1%/yr as expressed by a HAS-BLED score of 1. Given his life expectancy of approximately 50 additional years, this adds up to a lifetime risk for major bleeding of at least 50% (not considering his bleeding-prone occupation and the increase in bleeding risk with increasing age).

Therefore, two treatment options should be discussed with the patient: does he prefer to undergo LAAO or lifelong NOAC?

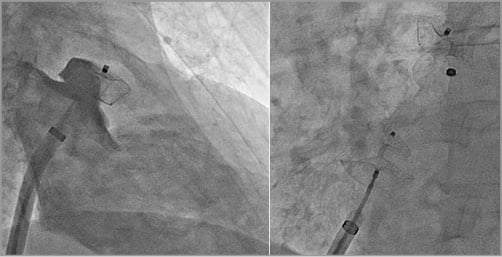

The patient suffered from a TIA. Two potential causes of his TIA were found - AF and a PFO. Preventing further strokes only by eliminating the stroke risk from AF is therefore insufficient. If the patient decides on lifelong oral anticoagulation, he is also protected from strokes via the PFO. As we learned from the subgroup analysis of the Randomized evaluation of recurrent stroke comparing PFO closure to established current standard of care treatment (RESPECT) trial, acetylsalicylic acid alone is inferior to PFO closure to prevent recurrent strokes (acetylsalicylic acid vs. PFO closure: 3.6% vs. 1.4%, HR 0.34, 95% CI: 0.12-0.94, p=0.03). Therefore, if the patient opts for LAAO, consistently the PFO should be closed. Both procedures are ideally carried out concomitantly by using the PFO for left atrial access, thereby avoiding the potential complications from transseptal puncture and facilitating PFO closure. LAAO is successful in 94% of cases, if a PFO is used for left atrial access and the PFO can be closed using the same sheath and delivery cable as for LAAO26 (Figure 2). In cases where LAA access through a PFO is challenging, we recommend PFO closure as a first step. The PFO occluder facilitates performing a more inferior and posterior transseptal puncture.

Figure 2. Combined left atrial appendage (LAA) and patent foramen ovale (PFO) occlusion. By using the PFO for left atrial access, the operator avoids a transseptal puncture, thereby rendering the procedure safer. LAA access and deployment of a device are feasible in over 90% of cases with a PFO. The procedures can be carried out using a single sheath and delivery cable.

Once the LAA and the PFO are closed and endothelialised, the patient has no further indication for any antiplatelet therapy. We would consequently recommend terminating antiplatelet therapy after six months. Another option is to prescribe lifelong acetylsalicylic acid.

PATIENTS WITH VALVULAR HEART DISEASE AND NON-VALVULAR ATRIAL FIBRILLATION UNDERGOING PERCUTANEOUS VALVE INTERVENTIONS (PATIENT 3)

Patients undergoing TAVI or percutaneous mitral valve repair (MitraClip® [Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA], Cardioband [Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA]) are typically elderly, multimorbid, and at high risk for bleeding27-29.

While reports of subclinical leaflet thrombosis after TAVI caught our attention30, studies are underway comparing different post-procedural anticoagulation regimens. Whether a more aggressive treatment (e.g., short course of oral anticoagulation) is justified needs to be answered in the near future.

Bleeding events after TAVI have a direct impact on survival. Subgroup analyses of the Placement of aortic transcatheter valves trial (PARTNER) showed worse outcome after TAVI in patients who experienced a major late bleeding event31. This was particularly pronounced in the subgroup of patients suffering from AF and experiencing a late bleeding event. While one-year mortality was 12.9% in patients in sinus rhythm (SR) and without bleeding event, it almost doubled in patients in SR who experienced a late bleeding event (one-year mortality 23.9%). One-year mortality was 26.2% in patients in AF who did not experience a late bleeding event. This increased to a 48.7% mortality rate in patients in AF who experienced a late bleeding event after TAVI. Almost every second patient in AF who experiences a major bleeding event after TAVI will die within the first year. This is evidence enough that we should take every possible measure to avoid bleeding after TAVI, particularly in AF patients. What solution would be better than LAAO?

A randomised multicentre trial under the lead of the University Hospital Zurich investigating the concept of combined TAVI and LAAO is currently recruiting (Comparison of Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion vs Standard Medical Therapy in Patients in AF Undergoing TAVI; NCT03088098).

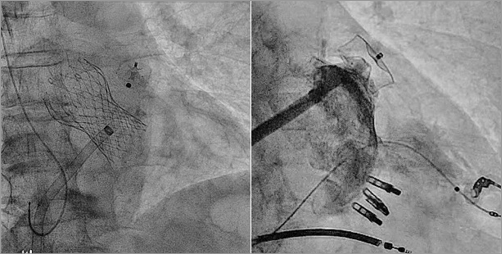

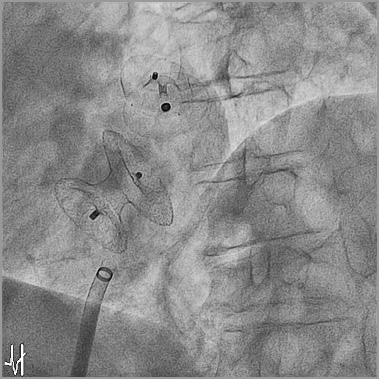

Today, we have data from retrospective trials investigating the safety of combining TAVI and LAAO32, as well as combining MitraClip and LAAO in a single procedure33 (Figure 3). Both trials prove the feasibility and safety of combining percutaneous valve procedures with LAAO.

Figure 3. Combined procedures. A) Combined TAVI and LAAO. B) Combined percutaneous mitral valve repair (MitraClip) and LAAO in a patient with an ICD-CRT.

In our elderly patient, both options (NOAC or LAAO) seem good and should therefore be discussed with the patient. In our centre, the patient would ideally be included in the ongoing trial.

UNDERWEIGHT, MULTI-MEDICATED PATIENTS AND PATIENTS WITH AN INDICATION FOR ANTIPLATELET THERAPY (PATIENT 4)

Underweight patients comprise a group at high risk for major bleeding when prescribed NOACs34. With a body mass index of <18.5, the risk for major bleeding increased fourfold (HR 4.1, 95% CI: 1.4-11.9, p=0.008) and the all-cause mortality was increased tenfold (HR 10.5, 95% CI: 2.9-37.6, p<0.001). Therefore, LAAO may be the preferred stroke prophylaxis in underweight patients suffering from AF.

Besides, our patient is on seven drugs for her cardiac condition. This raises the question of drug adherence. Compliance with NOACs varied from 67 to 79% in the randomised landmark trials13,14. A significant proportion of patients not being compliant and adherent to NOAC therapy was further confirmed in real-world studies35,36. In the latter retrospective study of >60,000 patients, more than half of the patients prescribed NOACs were uncovered in >20% of the days. This means that every second patient prescribed NOACs is not covered for >2 months per year. Not taking oral anticoagulants carries a higher risk of stroke.

The number of concomitant diseases as well as the number of drugs prescribed are associated with non-compliance37. On the other hand, compliance with LAAO is permanently 100% and therefore LAAO as other device therapies can be referred to as a mechanical vaccination38.

Combining oral anticoagulants with antiplatelet therapy increases the risk of bleeding. Bleeding risk was increased when dabigatran was combined with acetylsalicylic acid and even more so when combined with dual antiplatelet therapy in the RE-LY trial: major bleeding risk with single therapy low-dose dabigatran (110 mg bid) was 2.77%/yr, which increased to 4.72%/yr when combined with acetylsalicylic acid and clopidogrel39. In an AF population suffering from an acute coronary syndrome and having undergone percutaneous coronary stenting, the rate of clinically significant bleeding was 16.8% within the first year when given low-dose rivaroxaban in combination with clopidogrel40.

Our patient has several caveats (underweight patient with need for antiplatelet therapy and a high risk for non-adherence to therapy due to multi-medication) to be considered before prescribing a NOAC. LAAO is in our opinion the preferred treatment option. However, given the lack of a trial directly comparing NOAC versus LAAO, there is currently no evidence favouring one therapy over the other.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS: LEFT ATRIAL APPENDAGE CLOSURE FOR PRIMARY PRIMARY PREVENTION

LAAO today is performed for secondary prevention (patients in AF who suffered from a cerebrovascular event in the past), as well as for primary prevention (patients in AF who did not suffer from a cerebrovascular event in the past). In a selected subgroup of patients not suffering from AF and not having experienced a cerebrovascular event in the past, LAAO can make sense. For this, the term “primary primary prevention” was coined. A typical such case is a patient over 40 years in sinus rhythm with a large atrial septal defect (ASD) who is referred for percutaneous closure. The invariably large atria in such patients and the large device, irritating the interatrial septum at least for a while, expose them to a high risk for developing AF in the future. LAAO may be more difficult or even impossible with a large ASD occluder in place. Therefore, concomitant LAAO with ASD closure may make sense in such patients (Figure 4). However, the potential advantages and disadvantages of such an approach need to be discussed with each individual patient extensively. Our experience with such procedures documents the safety of such an approach41.

Figure 4. LAAO for primary primary prevention in a patient in sinus rhythm referred for closure of a large atrial septal defect (ASD). Concomitant LAAO was performed before ASD closure using a single sheath and delivery cable.

Procedural considerations

Preprocedural work-up and procedural details vary greatly between centres and operators, largely depending on centre experience and local circumstances. On one side of the spectrum, a multimodality work-up is performed for every patient, including computed tomography42 and transoesophageal echocardiography for all patients. On the other side of the spectrum, ad hoc LAAO is safely performed in patients where the decision on whether to perform LAAO or not depends on the findings of a coronary angiogram (e.g., need for coronary stenting with subsequent need for antiplatelet therapy – in which case LAAO is performed)43.

Intraprocedural guidance with transoesophageal echocardiography44 or intracardiac echocardiography45 is performed in most centres, whereas a more frugal approach with fluoroscopic guidance alone has also been proven to be a safe and effective alternative3.

Lastly, LAAO can safely be performed in combination with other procedures, such as coronary angiography, percutaneous coronary intervention, PFO or ASD closure, TAVI, percutaneous mitral valve interventions, or atrial fibrillation ablation. Whether this is feasible from a financial standpoint depends largely on the healthcare system and the willingness of a physician or hospital administration. From a patient perspective, combined procedures seem attractive46.

Conflict of interest statement

F. Nietlispach, I. Moarof, M. Taramasso, F. Maisano and B. Meier are consultants for Abbott. F. Nietlispach is a consultant for Medtronic and Edwards Lifesciences and is a shareholder of Edwards Lifesciences. F. Maisano is a consultant for Medtronic, 4Tech and Valtech and receives royalties from Edwards Lifesciences.