Abstract

Aims: To describe the characteristics of infective endocarditis (IE) after transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI).

Methods and results: This study was performed using the GAMES database, a national prospective registry of consecutive patients with IE in 26 Spanish hospitals. Of the 739 cases of IE diagnosed during the study, 1.3% were post-TAVI IE, and these 10 cases, contributed by five centres, represented 1.1% of the 952 TAVIs performed. Mean age was 80 years. All valves were implanted transfemorally. IE appeared a median of 139 days after implantation. The mean age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index was 5.45. Chronic kidney disease was frequent (five patients), as were atrial fibrillation (five patients), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (four patients), and ischaemic heart disease (four patients). Six patients presented aortic valve involvement, and four only mitral valve involvement; the latter group had a higher percentage of prosthetic mitral valves (0% vs. 50%). Vegetations were found in seven cases, and four presented embolism. One patient underwent surgery. Five patients died during follow-up: two of these patients died during the admission in which the valve was implanted.

Conclusions: IE is a rare but severe complication after TAVI which affects about 1% of patients and entails a relatively high mortality rate. IE occurred during the first year in nine of the 10 patients.

Abbreviations

IE: infective endocarditis

SAVR: surgical aortic valve replacement

TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation

Introduction

Prosthetic valve endocarditis is a severe complication which often entails dramatic clinical consequences owing to its high morbidity and mortality rates1. In the case of the aortic valve, this disease affects up to 10-15% of patients after prosthetic valve surgery and frequently necessitates reintervention2. During the last few years, transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has emerged as an attractive and feasible alternative for the treatment of severe aortic stenosis in symptomatic patients with high surgical risk. Recent multicentre trials have demonstrated that the two most commonly used TAVI systems –the Edwards SAPIEN valve (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) and the CoreValve® (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA)– are both safe and effective3,4. The transfemoral approach is the most frequent and is suitable for both types of valve. Success rates greater than 90% have been reported, as have 30-day procedural mortality rates lower than 10%5. Most complications after TAVI are technical and device-related, including significant periprosthetic paravalvular leaks6 and conduction disturbances7. In the absence of complications, survival and outcome are expected to be similar to those of patients without aortic stenosis8. Moreover, these prosthetic valves have good haemodynamic characteristics in the short and medium terms6.

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a potentially severe complication of TAVI9, with only a few cases described in the literature to date10-29. The incidence of this entity in large TAVI cohorts ranges between 0% and 2.3% after one to three years of follow-up14-18. TAVI valves are implanted mainly in elderly patients with frequent comorbidities in whom IE could entail a worse prognosis. Moreover, many of the patients with TAVI are inoperable, thus limiting options for treatment of IE. We aimed to review and describe the clinical and echocardiographic characteristics of patients with this disease and to determine the prognostic factors related to this uncommon post-TAVI complication.

Methods

We used the GAMES (Grupo de Apoyo al Manejo de la EndocarditiS [Management of Endocarditis Support Group]) database, a Spanish national prospective registry of consecutive patients with IE30 recruited from 26 Spanish hospitals between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2013. IE was defined according to the modified Duke criteria31. Multidisciplinary teams completed a standard case report form. Regional and local ethics committees approved the study, and patients gave their informed consent. Five centres contributed the 10 cases of IE after TAVI.

TAVI PROCEDURE

All patients were pre-treated with aspirin and clopidogrel. Heparin was administered during the procedure in order to maintain an activated clotting time above 250 s. The procedures were performed under general anaesthesia and with the aid of fluoroscopy and transoesophageal echocardiography to ensure accurate valve deployment. The stenotic valve was predilated with an undersized balloon to facilitate implantation, and the valve was placed during rapid pacing in the right ventricle or epicardium. If necessary, additional post-dilation was performed in cases of relevant paravalvular regurgitation. None of the patients presented a fever 48 hrs before valve implant, and all had a normal leukocyte count on the day of TAVI.

All patients with IE after TAVI were included, irrespective of valve location. An extensive number of variables was registered, including baseline clinical characteristics, procedural characteristics and valve model, presence of predisposing factors for IE, laboratory markers, and echocardiographic and microbiological findings (blood cultures). Follow-up (all patients) included treatment performed (type of antibiotics, surgery), complications related to IE, death, and cause of death. IE was classified as possible or definite. We also compared IE after TAVI with IE after surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), in the same period. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were expressed as mean±SD; qualitative variables were expressed as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables were compared using the t-test, and categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test when the chi-square test was not appropriate.

Results

We identified 10 cases of IE after TAVI in our series. Of the 952 TAVIs performed, 650 (68.3%) were CoreValve (610 transfemoral, 40 subclavian) and 302 (31.7%) Edwards SAPIEN (144 transapical, 158 transfemoral). A total of 1.1% were complicated by IE. Of the 739 cases of IE diagnosed during the study, 10 (1.3%) were post-TAVI IE and 221 (29.9%) post SAVR.

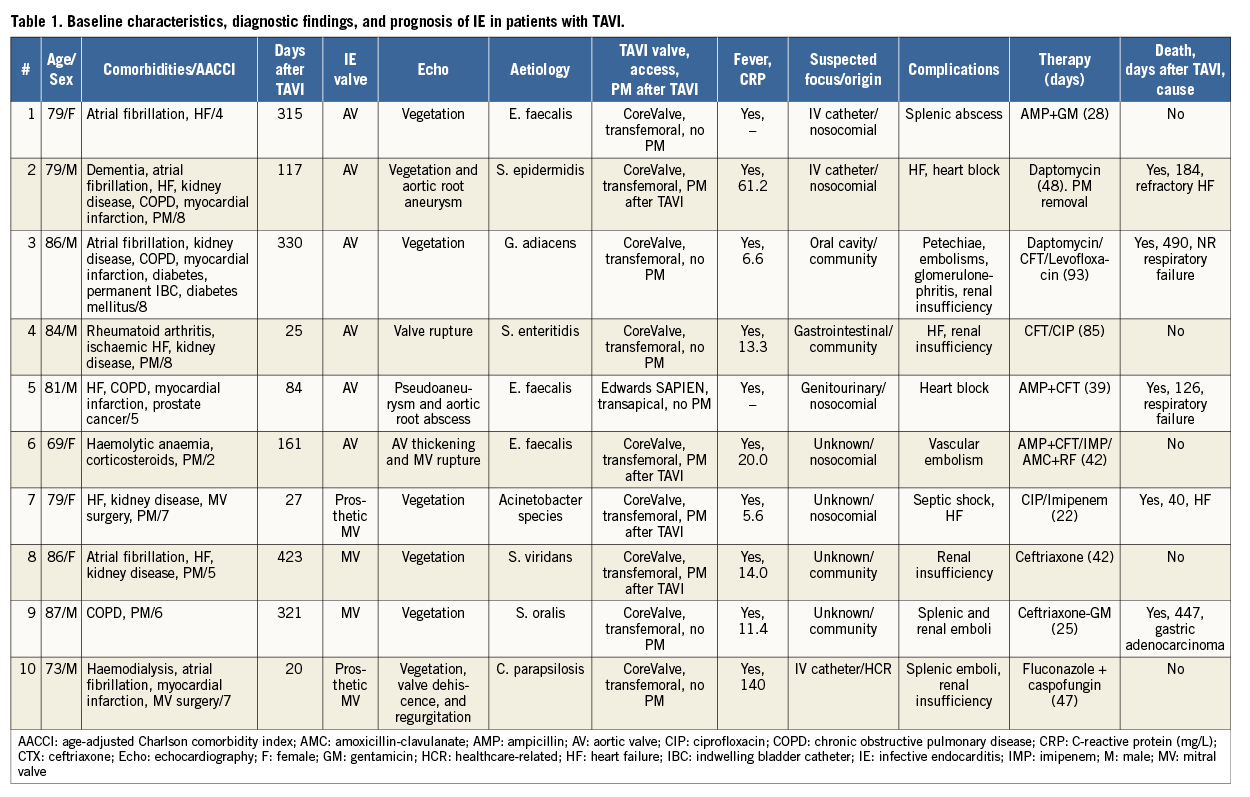

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 10 patients. Mean age was 80 years (range, 69-87 years) and six were men (60%). Nine patients received a CoreValve prosthesis and one an Edwards SAPIEN valve (patient 5). All valves were implanted transfemorally. Endocarditis appeared a median of 139 days after implantation. Comorbidity was high, with a mean age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index of 5.45. The most common underlying conditions included moderate or severe chronic kidney disease (five patients), atrial fibrillation (five patients), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (four patients), and ischaemic heart disease (four patients).

Six patients (patients 1 to 6) had IE in the aortic valve (TAVI endocarditis), and four (patients 7 to 10) presented only mitral valve involvement. When we compared patients with TAVI endocarditis and patients with exclusively mitral involvement, the only difference was that the latter group had a higher percentage of prosthetic mitral valves (0% vs. 50%). These mitral valves had been implanted 17 years before TAVI in one case (patient 7) and 25 years before TAVI in another (patient 10).

IE was definite in all cases except patient 10 (possible IE). All patients had fever and elevated C-reactive protein levels (range, 5.6-33.3 mg/L). IE-related vascular findings were detected in only one patient, who presented petechiae (patient 3). Mitral regurgitation due to IE was present in three patients (patient 6, severe; patient 9, mild; and patient 10, moderate). Patient 8 had severe mitral regurgitation before IE in the aortic valve.

All blood cultures were positive. The pathogens identified and antibiotic treatment administered are shown in Table 1. Gram-positive microorganisms predominated, as follows: Enterococcus faecalis (three), Streptococcus viridans or Granulicatella adiacens (three), and Staphylococcus epidermidis (one). Less common aetiologies were detected in the remaining three cases: Acinetobacter species, Salmonella Enteritidis, and Candida parapsilosis (one each). These three episodes occurred significantly earlier after TAVI (24 vs. 250 days).

Six patients presented nosocomial or healthcare-related IE (patients 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, and 10). The origins of IE were endovascular catheter (three patients), genitourinary tract (one patient), gastrointestinal tract (one patient), oral cavity (one patient), and unknown (four patients). Patients 4 and 7 also underwent urinary catheterisation before IE.

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed in all patients; transoesophageal echocardiography was performed in nine patients (not performed in patient 9, since IE was diagnosed with transthoracic echocardiography). Vegetations were demonstrated in seven cases (echocardiography findings are summarised in Table 1). Four patients presented systemic embolism: patients 1, 9, and 10 presented splenic embolism (with splenic abscess in patient 1); patient 9 also presented kidney embolism and abscess, and patient 7 presented central nervous system ischaemia not related to IE. Patient 6 presented peripheral arterial embolism. Renal function worsened in five patients, and three patients presented heart failure.

After multidisciplinary assessment, surgery was indicated in five patients, although it was only performed in patient 2, owing to technical difficulties or severe comorbidity which rendered surgery impossible in the remaining four. Patient 2 was readmitted 117 days after TAVI due to worsening heart failure, and IE was diagnosed during admission. The patient successfully underwent reparative surgery of the aortic root but was admitted eight days after being discharged owing to symptomatic high-degree atrioventricular block and refractory heart failure. The patient died 11 days later. A total of five patients died during follow-up. Patients 4 and 7 died during the admission in which the valve was implanted.

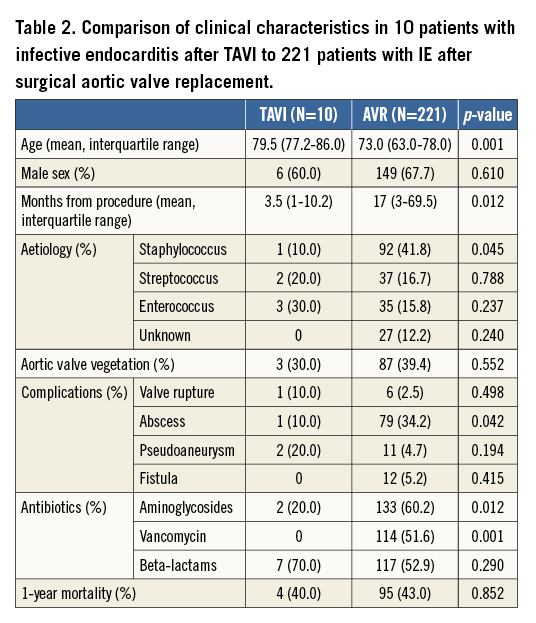

The comparison of the clinical characteristics of patients with IE after TAVI to patients with IE after SAVR is depicted in Table 2. TAVI patients presented a more advanced age but had similar one-year mortality.

Discussion

Our results show that IE is a rare but severe complication in patients undergoing TAVI. It affects about 1% of patients and has a relatively high mortality rate, reaching 50% during follow-up (five out of ten). In our study, IE was recorded during the first year after TAVI in nine of the 10 patients and during the first month in three. Two patients died during the admission in which the valve was implanted. Four patients presented only mitral valve IE, two of them in a metallic prosthesis.

The prevalence of IE patients receiving TAVI seems to be similar to that of patients undergoing open aortic valve surgery, as prosthetic valve endocarditis after surgical replacement has been estimated to occur at a rate of 0.3% to 1% per patient-year2. In the Placement of AoRtic TraNscathetER Valves (PARTNER) cohort B trial3, the incidence of IE at two years was similar in both groups (1.5% in the TAVI group and 1.0% in the surgery group). After open aortic valve surgery, IE is associated with poor prognosis and high rates of morbidity, reintervention, and mortality2. Prognosis seems to improve with timely surgical intervention and close follow-up32.

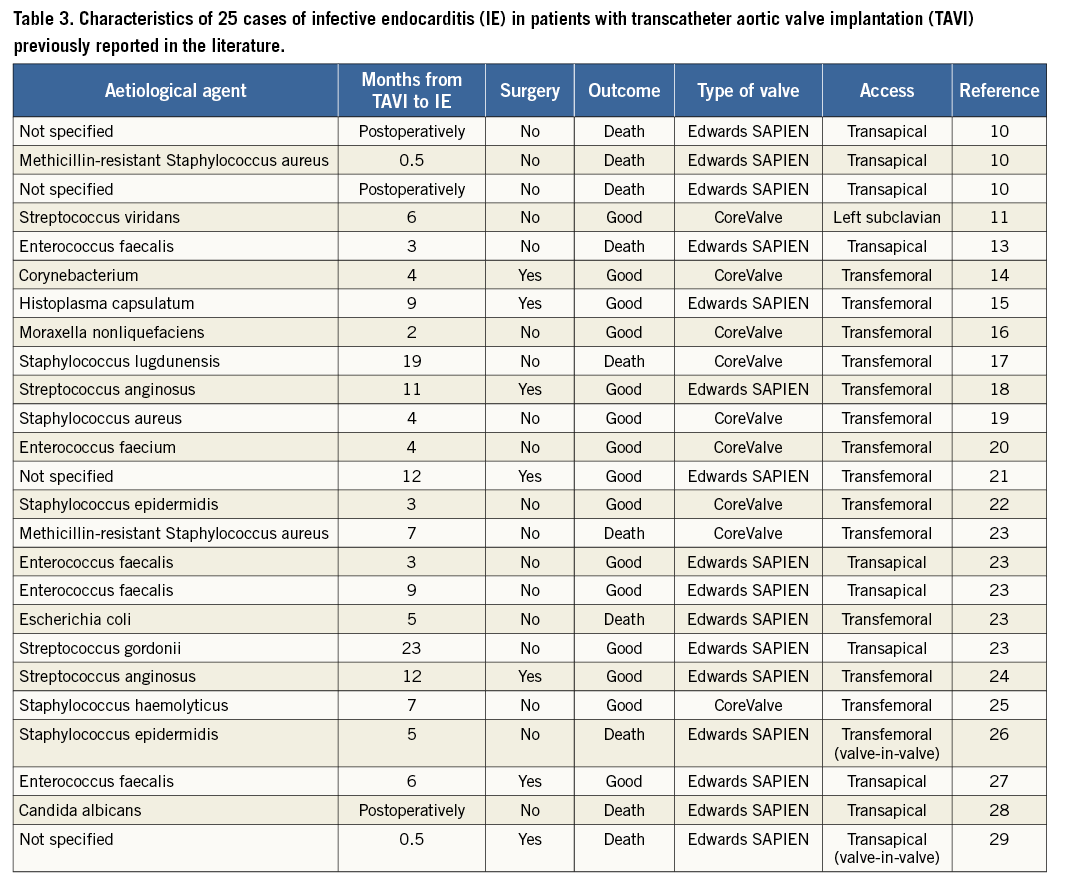

TAVI has proven to be a safe and effective alternative to conventional aortic valve surgery, especially in patients with high surgical risk33,34. IE following TAVI is a rare but severe complication, with few previously reported cases10-29 (Table 3). The vast majority of cases occur during the first year after TAVI. In an autopsy study, Loeser et al10 studied 13 patients after TAVI and found three cases of acute IE (23%); the patients died one, three, and 14 days after the procedure. Interestingly, the endocarditis was not identified while the patient was alive, suggesting that many cases of post-TAVI IE go undiagnosed. In their single-centre series of four cases of post-TAVI IE with a definite diagnosis and one with a possible diagnosis, Puls et al23 also concluded that it might be particularly difficult to diagnose IE after TAVI. In our series, the mean time between TAVI and IE was 174 days (range, 20-423 days). Patient 10 presented IE 20 days after TAVI, with blood cultures that were positive for Candida. Early IE due to Candida after TAVI was reported28 in a 91-year-old man who had previously undergone TAVI with an Edwards SAPIEN transapical valve and developed septic shock. He died 54 days after TAVI. Staphylococci, fungi, and Gram-negative bacilli are the main causes of early prosthetic valve endocarditis (<12 months after implantation) in studies of surgical prostheses35. In our series, IE was detected during the first year after implantation, except in patient 8, who developed mitral valve IE caused by S. viridans. A possible explanation for the early onset of IE is that TAVI is usually performed in the catheterisation laboratory, as most centres do not have a so-called hybrid room. Consequently, the risk of early infection increases, since the disinfection and sterilisation criteria are not as stringent in the catheterisation laboratory as in the operating room. In addition, since elderly patients with comorbidities are less immunocompetent, the incidence of bacteraemia is higher in TAVI patients.

Different types of infective complication have been recorded. In their single-centre study, Onsea et al36 retrospectively assessed the number of infective complications in patients undergoing TAVI between 2008 and 2011. Eleven of 73 patients developed a post-procedural infection, but only one case was attributed to the procedure itself (infection of a surgical groin scar), as most were related to urinary tract and bronchopulmonary infections. The authors found no cases of IE and no positive blood cultures, and concluded that TAVI in a catheterisation laboratory is not associated with an increased risk of infective complications. In the transfemoral approach, groin access-site infections seem to be rare36, although obesity has been associated with a higher incidence of transapical access site infection37. In any case, local infections do not seem to entail worse prognosis and are not clearly associated with IE. As for height of implantation, it has been suggested that, when implanted too low, the infected prosthesis can enter into contact with the anterior mitral valve leaflet, thus facilitating formation of aneurysms11,12. Furthermore, residual paravalvular leak, which is not uncommon after TAVI6, has been suggested to predispose to IE23, as have advanced age and the presence of comorbidities.

In our series, all patients presented with fever, elevated C-reactive protein, and positive blood cultures; therefore, our data highlight the importance of obtaining microbiological samples before starting empiric antimicrobial therapy in patients with previous TAVI and fever. Samples should be taken irrespective of the presence of valve murmurs. In fact, no new or different valve murmurs were detected in the physical examination on admission in any of our patients. Positron emission tomography and computed tomography (PET/CT) were not performed in our patients. Although PET/CT is currently not sufficiently adequate for the diagnosis of IE because of its low sensitivity38, improvements such as patient preparation and technical advances may increase its sensitivity, and this technique could have an important role in the future.

As expected, patients from our series were elderly and presented frequent comorbidities, findings that are consistent with the observation that TAVI is mostly performed in those with high surgical risk. As comorbidity is an independent predictor of poor prognosis in patients with IE39, high mortality is to be expected. Chronic kidney disease and heart failure are important predictors of poor prognosis in patients with prosthetic valve IE32; both were frequent in our series. Two of the three patients with worsening heart failure eventually died. Most patients in such situations are considered inoperable, probably because of their poor prognosis. Moderate-severe chronic kidney disease was present in five patients, and three finally died.

Five patients in our series died during follow-up: in two cases, death was because of complications clearly related to IE. The remaining patients presented non-cardiac causes of death. Surgery was only performed in one patient, although it was considered indicated after multidisciplinary assessment in five cases. In elderly patients with IE after open aortic valve replacement, surgical intervention may be life-saving40. However, TAVI is mostly performed in elderly patients with frequent comorbidity and high or even prohibitive surgical risk, and this could explain why most patients were treated conservatively. In spite of this fact, in our series, one-year mortality was similar in patients with IE after TAVI and in those with IE after SAVR (Table 2).

Nine of our ten patients with IE received a CoreValve TAVI; however, the Edwards SAPIEN valve was only used in about a third of our patients. Our data are insufficient to determine if one valve type is more prone to IE. TAVI with the CoreValve has a higher rate of atrioventricular block and permanent pacemaker implantation than with an Edwards SAPIEN7, and this could be a factor concerning IE development. On the other hand, from the 25 previously reported IE after TAVI (Table 3), only nine (36%) were in patients who received a CoreValve. Again, this could be related to the higher use of one valve type in those institutions.

Little is known about therapy of IE in TAVI. When the disease is suspected, a multidisciplinary approach should be adopted in order to ensure correct diagnosis and treatment. Prophylaxis should be tailored to the patient. The Valve Academic Research Consortium has recommended reporting IE as an individual endpoint41 after TAVI, although prophylaxis of endocarditis before TAVI is not mandatory and often depends on hospital preferences and protocols. Both our findings and those reported in the literature show that post-TAVI IE is a severe complication for which adequate prophylaxis must be considered before invasive procedures and during follow-up11. In addition, special attention ought to be paid when performing procedures that might cause bacteraemia, including catheter management and catheterisation.

To our knowledge, this is the first multicentre series to analyse IE after TAVI. Our results show that IE is a rare but severe complication which affects about 1% of patients undergoing TAVI and has a relatively high mortality rate, reaching 50% during follow-up (five out of ten). In nine of our 10 patients, IE occurred during the first year after TAVI. Further studies are needed to improve management of such a feared complication.

| Impact on daily practice More emphasis should be placed on disinfection and sterilisation in the catheterisation laboratory, with strict hygiene and specific staff education similar to that provided for the operating room. High-efficiency particulate air filtered laminar airflow and criteria regarding air control would be welcome. Moreover, in many TAVI patients, IE is nosocomial, that is, secondary to invasive techniques, such as endovascular or urinary tract catheterisation, which should be performed with extreme care. Patients should be more closely monitored during the first year after TAVI, and physicians should have a low threshold of suspicion. Echocardiography and blood culture are key approaches in patients with IE. |

Funding

This work was supported in part by the RIC (Red de Investigación Cardiovascular). (RD 12/ 0042/0001).

Conflict of interest statement

M. Martinez-Sellés has received fees for lecturing/support for research from Edwards Lifesciences. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.