Abstract

Aims: To evaluate the effects of access route upon clinical results and quality of life (QoL) in patients undergoing either transfemoral (TF-TAVI) or transapical balloon-expandable transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TA-TAVI) in the real world.

Methods and results: A prospective analysis was performed upon 264 consecutive patients receiving TF-TAVI or TA-TAVI. QoL was assessed using the EQ-5D questionnaire. At baseline, TA-TAVI patients reported significantly more problems in mobility, self-care, usual activities and lower overall health status domains (p<0.01 for all). At 30 days, the TF-TAVI group reported fewer problems with usual activity (p=0.01) and pain/discomfort (p<0.01), and higher EQ-5D index and visual analogue scale (VAS) (p=0.01 and p<0.01, respectively) than the TA-TAVI group. Nevertheless, the absolute improvements (ΔEQ-5D index and ΔEQ-5D VAS) were larger in the TA-TAVI group, with most dramatically marked QoL absolute improvements (p<0.01 and p=0.02, respectively). By one year, notwithstanding higher all-cause mortality in the sicker TA-TAVI group, there were no differences between groups in any EQ-5D domain. Indeed, surviving TA-TAVI group’s greater absolute improvements remained (p<0.01).

Conclusions: QoL is greater at the earlier time point of 30 days in the TF-TAVI cohort but equatable by one year. However, the magnitude of improvement in QoL is greater in the TA-TAVI patients at both 30 days and one year.

Introduction

Over the past decade, transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has emerged as an effective treatment for patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS) who are considered at excessive perioperative risk for surgical aortic valve replacement (sAVR)1-4. Two-year results from inoperable5 and three-year results from high-risk operable randomised Placement of AoRTic TraNscathetER Valve (PARTNER) trial cohorts6 confirmed that TAVI is better than medical therapy and is non-inferior to sAVR in these patients. The follow-up results from randomised PARTNER trials established a significant reduction in symptoms, similar in both TAVI and sAVR groups, and this was maintained for at least two years.

Given that the decision to intervene on severe AS is driven by the appearance of significant symptoms, assessment of the impact of TAVI upon patients’ quality of life (QoL) –in addition to traditional endpoints such as mortality and morbidity– is paramount7,8. The introduction of any new technology requires the assessment of cost-effectiveness including both length and quality of life.

Patients undergoing TAVI in the PARTNER trial demonstrated improvements in generic and specific health-related QoL measures at both one month and 12 months9. However, the impact of the access route upon QoL is less clear. Reynolds et al10 compared QoL between TAVI and sAVR at one, six and 12 months and found transapical TAVI (TA-TAVI) patients did not show any QoL benefit compared to sAVR. A direct transfemoral TAVI (TF-TAVI) versus TA-TAVI health status comparison has yet to be performed.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the effects of access route on clinical results and QoL in patients undergoing either TF-TAVI or TA-TAVI using the Edwards SAPIEN or SAPIEN XT bioprosthesis (Edwards Lifesciences Inc., Irvine, CA, USA).

Methods

A prospective analysis was performed upon data from 264 consecutive patients receiving TF-TAVI or TA-TAVI for severe symptomatic AS at two European centres (St. Thomas’ Hospital, London, and Cardiologico Monzino Centre, Milan) between January 2008 and October 2011. Data were taken from patients enrolled in the Edwards SAPIEN Aortic Bioprosthesis European Outcome Registry (SOURCE) (Milan) and Edwards SAPIEN XT Aortic Bioprosthesis European Outcome Registry (SOURCE XT) (Milan and London).

Across the two centres too few transaortic procedures were performed within the registries –and so without QoL– and there were no subclavian implants. Severe AS was defined as an aortic valve area of <1 cm2 or a mean transvalvular gradient of at least 40 mmHg or a peak velocity of >4.0 m/s on transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), stress or transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE)11.

All patients underwent assessment as previously described12. Each case was considered by a multidisciplinary team comprising interventional cardiologists, imaging-specialist cardiologists and cardiovascular surgeons. Patients were accepted for TAVI when it was agreed that conventional surgery was of excessive risk according to the European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE)13 or they were patients who suffered from specific conditions likely to contribute to excessive perioperative risk that were not reflected in the EuroSCORE: surgical technical concerns, morbid obesity, porcelain aorta and other comorbidities14. Patients unsuitable for TF-TAVI due to peripheral vascular disease underwent anterograde TA-TAVI. All patients received Edwards SAPIEN or SAPIEN XT balloon-expandable prostheses as previously described3,15,16.

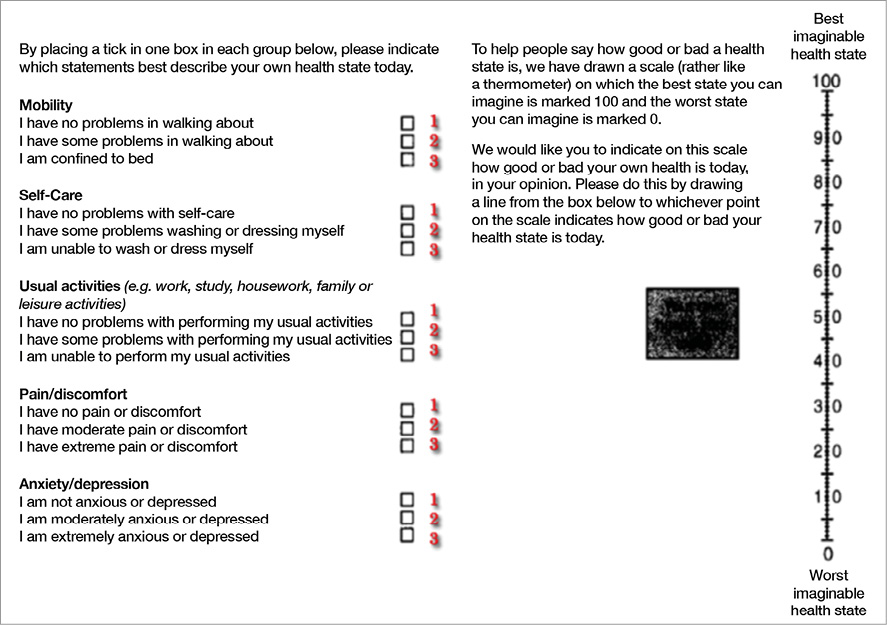

QoL was assessed using the self-reported European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire, a health-related quality of life measure, consisting of five three-level items, representing various aspects of health: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression17. Respondents could score each domain from one (no problems) to three (extreme problems). A visual analogue scale (EQ-5D VAS) was also included in the EQ-5D for subjects to rate their health status between the worst imaginable health state (score 0) to the best imaginable health state (score 100) (Figure 1). A utility index (EQ-5D index) score was calculated for each by applying the time trade-off-based valuations from a general UK population sample to the observed EQ-5D profile, as data from an Italian norm are not available at the present time17,18.

Figure 1. EQ-5D self-classifier and visual analogue scale. Respondents can score each domain from one (no problems) to three (extreme problems). A visual analogue scale is included in the EQ-5D to enable the respondent to provide a self-rating of their own health status between the worst imaginable (score 0) and the best imaginable health state (score 100). Reproduced from: Rabin R, Oemar M, Oppe M. On behalf of the EuroQol Group. EQ-5D-5L User Guide. Basic information on how to use the EQ-5D-5L instrument. Version 4.0. www.euroqol.org, by permission of EuroQol Group Foundation.

An appropriately trained researcher administered the EQ-5D questionnaire according to the EuroQol Group guidelines17 the day before operation. Follow-up questionnaires were administered during scheduled follow-up visits, by mail or by telephone interview. Validated translations of the original questionnaires - obtained exclusively from the EuroQol Executive Office - were provided to non-English speakers.

The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the relevant local research ethics committees.

STUDY ENDPOINTS

The primary endpoints were health-related QoL data at baseline, 30 days and one year using the EQ-5D descriptive system, further dichotomised into “no problems” (i.e., level one) and “problems” (i.e., levels two and three), as well as the “global” EQ-5D index and analogue EQ-5D VAS score. Secondary endpoints were defined on the basis of Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC) criteria19.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Categorical variables are summarised as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). Comparison of categorical variables (e.g., the incidence of “problems” in each EQ-5D dimension) was performed by χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were analysed by the Student’s independent t-test or two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test (e.g., the magnitude of improvement, “delta”, for the EQ-5D index and analogue EQ-5D VAS score). Intra-individual comparisons of continuous variables before and after transcatheter procedures were performed by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Time-related categorical variables were analysed by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank method. The time course of continuous variables (e.g., 30-day and one-year EQ-5D index and EQ-5D VAS) was compared by repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), adjusting for baseline values of the same variables. Missing data from dead people and unattended follow-up interviews were treated as missing data test-by-test. All tests were two-sided with a significance level of 0.05 and performed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics version 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

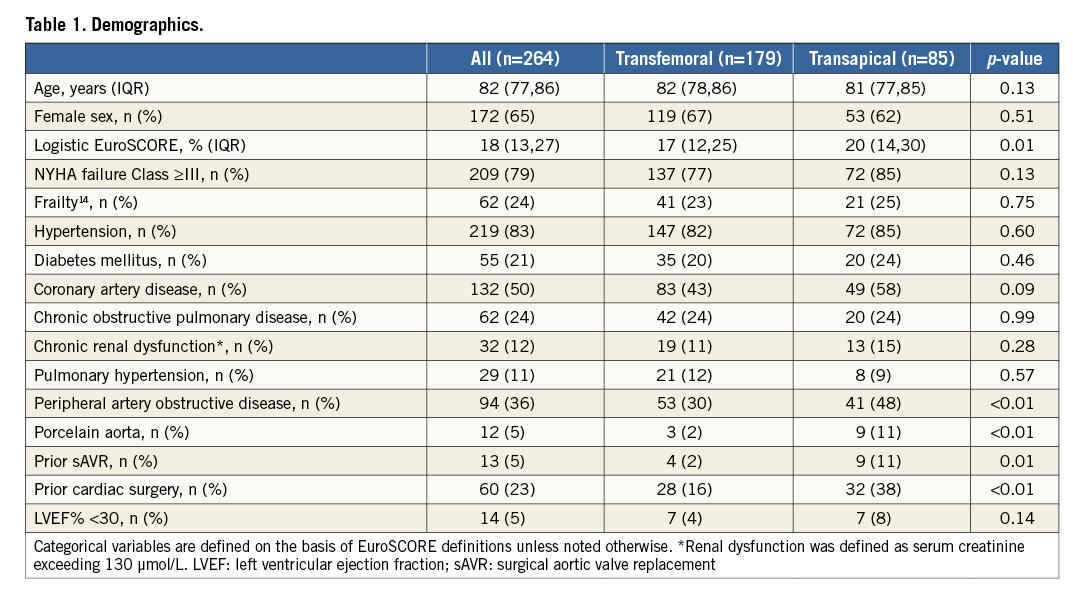

BASELINE DEMOGRAPHICS

Baseline characteristics of these patients, stratified by TAVI procedural approach, are shown in Table 1. All patients had severe symptomatic AS (mean aortic valve area [AVA] 0.66 [IQR 0.51-0.76] cm2). One hundred and seventy-nine (68%) patients underwent TF-TAVI and 85 (32%) patients underwent TA-TAVI. Patient characteristics in the two cohorts were significantly different according to higher logistic EuroSCORE in the TA-TAVI patients (17% [IQR 12-25%] vs. 20% [IQR 14-30%], p=0.01), greater incidence of peripheral artery disease (53 [30%] vs. 41 [48%], p<0.01), porcelain aorta (3 [2%] vs. 9 [11%], p<0.01), prior surgical aortic valve replacement (4 [2%] vs. 9 [11%], p=0.01) and prior cardiac surgery (28 [16%] vs. 32 [38%] p<0.01). There was no significant difference in severity of AS: mean transaortic valve gradient was 51±15 mmHg vs. 50±16 mmHg (p=0.57) and AVA 0.64 cm2 (IQR 0.51-0.74 cm2) vs. 0.66 cm2 (IQR 0.55-0.79 cm2) (p=0.23). Seven (4%) TF-TAVI patients and seven (8%) TA-TAVI patients had a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <30% (p=0.14).

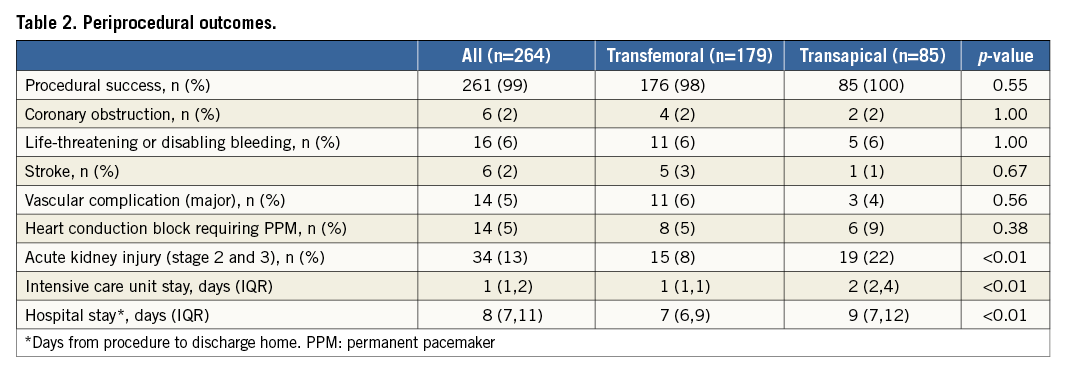

PERIPROCEDURAL OUTCOMES

Early procedural results are summarised in Table 2. Procedural success was comparable between the two cohorts (98% [176 procedures] for the TF-TAVI group vs. 100% [85 procedures] for the TA-TAVI group, p=0.55). The thirty-day mortality rate was 4% (seven) for the TF-TAVI group and 2% (two) for the TA-TAVI group (p=0.72). There was a low incidence of stroke in both groups. The post-procedural intensive/coronary care unit stay was shorter for the TF-TAVI cohort (one day [IQR 1-1] vs. two days [IQR 2-4], p<0.01) as was the overall in-patient stay (seven days [IQR 6-9] vs. nine days [IQR 7-12], p<0.01).

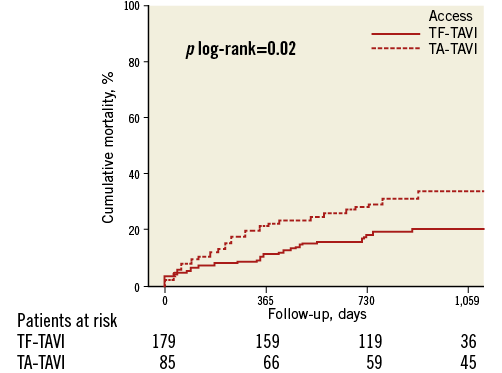

At one year, all-cause mortality was lower in the TF-TAVI group than in the TA-TAVI group (11% vs. 22%, p=0.02) (Figure 2). Before receiving TAVI, 72 (85%) of TA patients and 137 (77%) of TF patients were in New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class III-IV. At 30 days, 75 (90%) of TA patients and 170 (99%) of the TF patients were in NYHA functional Class I-II (p<0.01). At one year, NYHA Class had improved by ≥1 Class in both groups (p<0.01, for both). After adjustments for baseline values ∆NYHA during follow-up was significantly improved in the TF-TAVI group at 30 days (p=0.05), with no difference between TF-TAVI and TA-TAVI groups at one year (p=0.70).

Figure 2. Time-to-event curves for mortality from any cause.

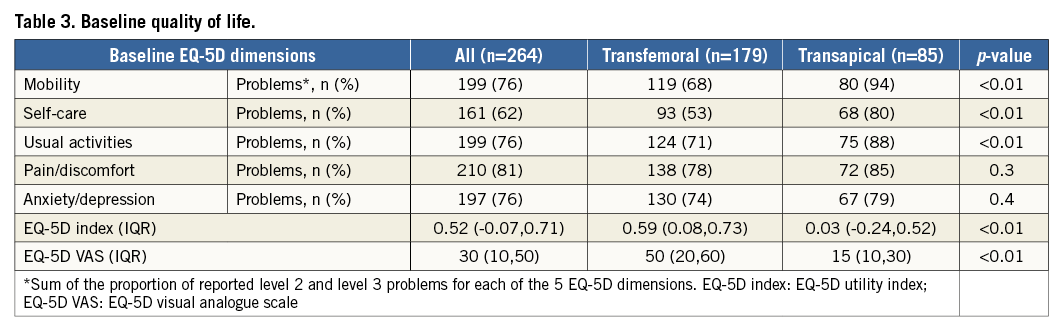

QUALITY OF LIFE

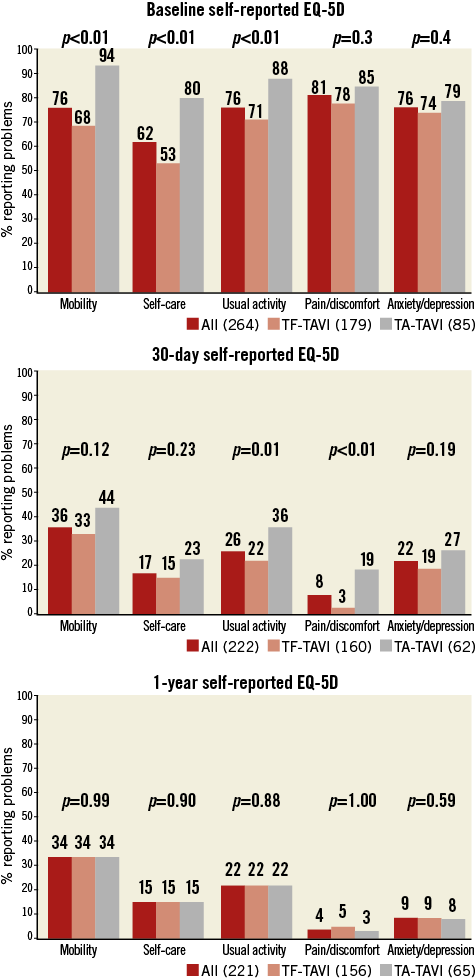

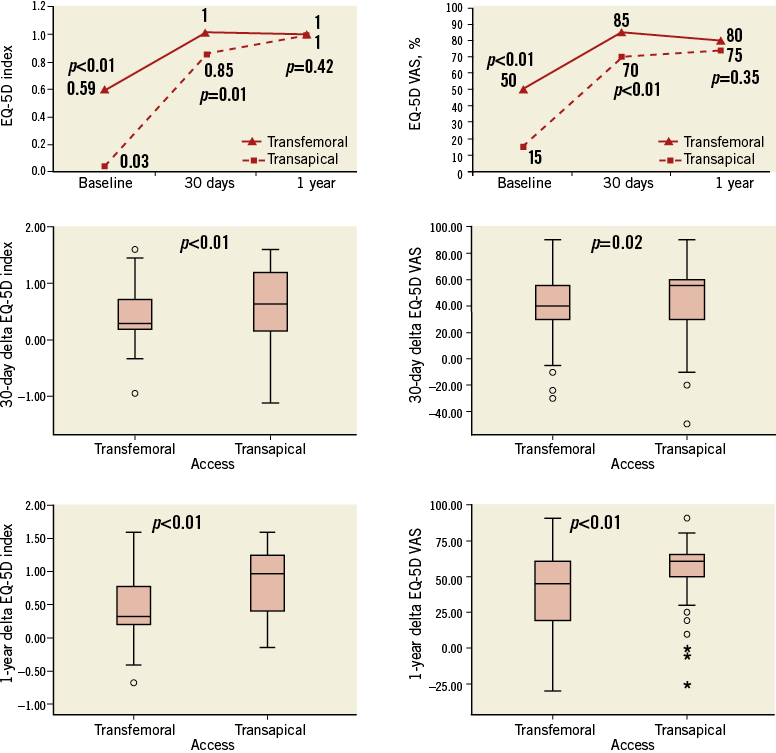

At baseline, TA-TAVI patients reported more problems (EQ-5D score ≥2) in mobility (80 [94%] vs. 119 [68%], p<0.01), self-care (68 [80%] vs. 93 [53%], p<0.01) and usual activity (75 [88%] vs. 124 [71%], p<0.01) domains, a lower EQ-5D index (0.03 points [IQR -0.24-0.52] vs. 0.59 points [IQR 0.08-0.73], p<0.01) and EQ-5D VAS (15 points [IQR 10-30] vs. 50 points [IQR 20-60], p<0.01) (Table 3, Figure 3).

Figure 3. Quality of life profile of the populations. % reporting problems (EQ-5D score ≥2) in each domain at baseline, 30 days and one year.

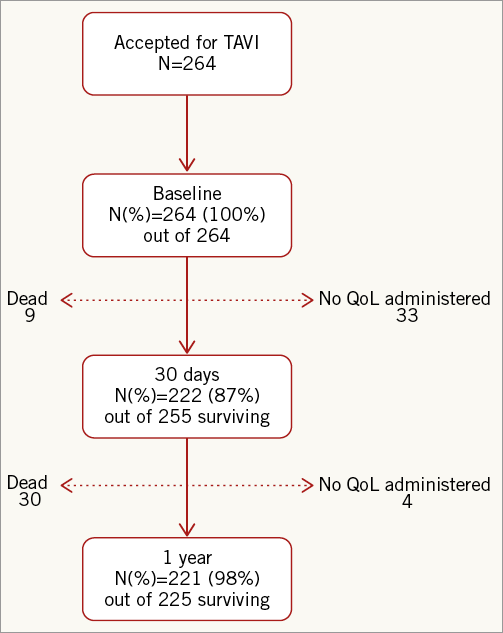

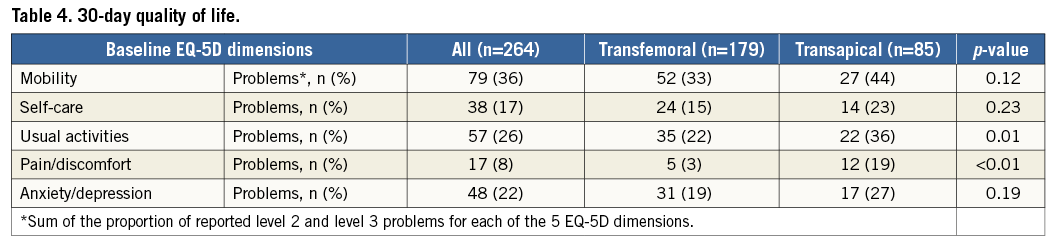

Follow-up questionnaires were obtained from 87% of surviving subjects at 30 days. At one year, follow-up questionnaires were obtained from 98% of TF- and TA-TAVI surviving subjects (Figure 4). At 30 days, the TF-TAVI group reported fewer problems with usual activity (35 [22%] vs. 22 [36%], p=0.01) and pain/discomfort (5 [3%] vs. 12 [19%], p<0.01) (Table 4). EQ-5D index and EQ-5D VAS values were higher in the TF-TAVI cohort (EQ-5D index 1 [IQR 0.85-1] vs. 0.85 [IQR 0.74-1], p=0.01, and EQ-5D VAS 85 points [IQR 75-90] vs. 70 points [IQR 60-80], p<0.01). However, the absolute improvements compared to baseline were most marked in TA-TAVI patients: ΔEQ-5D index was 0.62 (IQR 0.15-1.21) vs. 0.29 (IQR 0.19-0.70) (p<0.01) and ΔEQ-VAS calculated as 55 points (IQR 30-61) vs. 40 points (IQR 30-56) (p=0.02) (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Flow chart of patients who filled in the EQ-5D quality of life questionnaire.

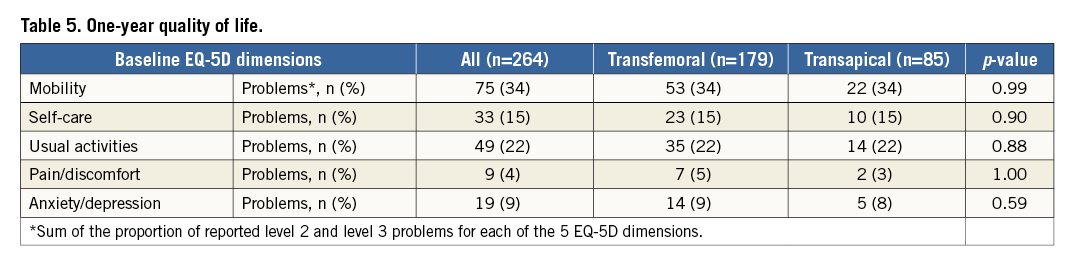

By one year there were no differences between TF-TAVI and TA-TAVI patients in any EQ-5D domain (Table 5, Figure 3), in EQ-5D index and in EQ-5D VAS (Figure 5). Nevertheless, the greater absolute improvement in the TA-TAVI group remained (ΔEQ-5D index 0.97 points [IQR 0.41-1.24] vs. 0.31 points [IQR 0.20-0.77], p<0.01, and ΔEQ-5D VAS 60 points [IQR 50-65] vs. 45 points [IQR 20-60], p<0.01) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Improvements in quality of life. Top: time course of “global” EQ-5D index and EQ-5D VAS score. Middle and bottom: 30-day and one-year absolute improvement in EQ-5D index and EQ-5D VAS.

Discussion

Catheter-based therapies represent potentially transformational technologies for valvular heart disease. With evidence of feasibility, safety and mortality benefit established5,6 we must now identify other benefits such as in QoL. This impacts upon cost-effectiveness and thus diffusion of the technology.

Our study confirms that TAVI in high-risk surgical candidates is associated with excellent short and medium-term results in terms of morbidity and mortality and that TAVI results in significant improvements in health-related QoL, maintained to one year. This is in keeping with the PARTNER trial and previous reports9,20-22.

Whilst both access site cohorts demonstrated QoL improvements, our analysis identified important features differentiating the two. The baseline characteristics confirm that the TF-TAVI and TA-TAVI have significant differences, with the latter group having greater comorbidities and representing a higher perioperative risk23,24. They also had significantly more dyspnoea, with greater numbers of patients in NYHA Class III and IV, and their lower baseline EQ-5D index of 0.03 points (IQR –0.24-0.52) suggests impairment of similar magnitude to a stroke25.

Reassuringly, despite these differences, 30-day mortality was not significantly different between access groups (4% in the TF-TAVI group and 2% in the TA-TAVI group, p=NS), and the incidence of complications such as stroke was low (Table 2).

TA-TAVI represents a sicker group of patients. The predictive factors for acute kidney injury (AKI) may include chronic renal dysfunction, peripheral vascular disease and diabetes mellitus26. Fifty-seven (67%) of the TA-TAVI cohort had ≥1 of these risk factors compared to 87 (49%) of TF-TAVI patients (p=0.02) and ≥2 were present in 17 (20%) in the TA compared to 18 (10%) in the TF group (p=0.02), perhaps identifying a higher risk cohort for AKI.

For many patients in this high-risk cohort, improvements in QoL are arguably more important than improvement in longevity and perhaps more realistic. Similar to the PARTNER A findings, we identified differences in the QoL and recovery between cohorts at 30 days10. The TA-TAVI patients reported more problems in the pain/discomfort and “usual activities” domains (Table 4, Figure 3), which could be attributed to access-specific factors such as the postoperative pain caused by rib retraction, dissection of the pleura and intercostal nerve damage12. The TA-TAVI group in the PARTNER A trial showed a worse outcome in terms of QoL compared to sAVR10. However, this group constituted the first experience of transapical TAVI in the United States. The current paper contains information on a group with a much larger experience with TA-TAVI and a combination of improvements in patient selection, procedural techniques and device technologies.

As in previous reports, the absolute QoL measures were higher in TF-TAVI patients (EQ-5D index and EQ-5D VAS), but the improvements were most dramatic in the TA-TAVI group. When appreciated in the context of similarly low 30-day mortality, despite demonstrably higher-risk patients, this represents a powerful fillip to use of this route.

At one year, mortality was significantly higher in the TA-TAVI group, likely reflecting the difference in comorbidities. Nonetheless, surviving TA-TAVI patients now had similarly high QoL scores to the TF-TAVI group and more marked improvement from baseline (Table 5, Figure 5).

As with all health-related QoL measures, the perceived effects of an intervention upon physical, social and emotional status can be more marked in those who are initially more symptomatic, who are therefore more “functionally” impaired25. The equatability of the absolute values at 30 days and one year and the similar percentage of patients reporting no problems in all domains at the latter time point certainly illustrate the positive impact of TA-TAVI and confirm that of TF-TAVI.

Limitations

Italian cohort patients started with lower baseline QoL indices (Italian baseline EQ-5D index 0.69 [IQR 0.52-0.80] vs. UK 0.73 [IQR 0.36-0.80], Italian baseline EQ-5D VAS 50 [IQR 30-70] vs. UK 60 [IQR 50-75], p<0.01 for both). The one-year EQ-5D index and EQ-5D VAS were greater in the Italian cohort (Italian one-year EQ-5D index 1 [IQR 1-1] vs. UK 0.81 [IQR 0.70-1], Italian one-year EQ-5D VAS 90 [IQR 80-100] vs. UK 75 [IQR 60-85], p<0.01 for both). Of note, a limitation of the EQ-5D questionnaire is that there are no particular 3L values available for an Italian population. The consensus and the opinion of the EuroQol Group are to apply the UK TTO scoring algorithm. This may partly explain the per country differences.

The EQ-5D questionnaire has been criticised as a non-specific instrument - but no aortic stenosis specific QoL tool currently exists. Several previous studies have shown that both sAVR and, more recently, TAVI improve health status and QoL compared with baseline for patients with severe AS using other measures (SF-12, SF-36, etc.). The QoL instrument used in this study, the EQ-5D, is widely employed in the cardiology field, involving populations affected by coronaropathies, by heart failure, associated with heart transplant, and in the rehabilitation programmes as well18,25,27. Given the relatively high one-year mortality associated with TAVI, the proportion of patients with available data diminished over time. TA-TAVI mortality was higher at one year. Therefore, the QoL improvements are based on the (fitter) surviving patients and the results are favourable, as expected. Rather than a bias, it is representative of the clinical picture in survivors.

Conclusions

For every Heart Team performing TAVI, QoL should be a key outcome, given the limited life expectancy of this population. Although death is the lowest possible functional status, patients can feel survival marked by reduced physical function or independence as a worse outcome.

TAVI is effective in improving QoL with both TA-TAVI and TF-TAVI approaches in patients not suitable for sAVR. Overall health-related QoL is greater at 30 days in the TF-TAVI cohort but equatable by one year. However, the magnitude of improvement in QoL is greater in the TA-TAVI patients at both 30 days and one year.

| Impact on daily practice The mortality benefit of TAVI in inoperable and high-risk patients is clear; however, the effect on quality of life (QoL) is in many ways just as important as its duration. In keeping with existing literature, the improvement in QoL is marked at 30 days in the TF-TAVI cohort; yet, despite the higher risk profile of the TA-TAVI cohort, they too demonstrate improvement in QoL at 30 days and by 12 months this is comparable to the TF-TAVI patients. When appreciated in the context of a similarly low 30-day mortality despite demonstrably higher risk transapical patients, these results represent a powerful mandate for use of the TA-TAVI access route. |

Funding

S. Redwood, M. Thomas and M. Khawaja have received research funding from Edwards Lifesciences (Irvine, CA, USA). M. Khawaja is funded by a British Heart Foundation Clinical Research Training Fellowship FS/12/15/29380.

Conflict of interest statement

V. Bapat, C. Young, S. Redwood, M. Fusari and M. Thomas are proctors and consultants for Edwards Lifesciences. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.