Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has transformed the treatment of high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis, with over a hundred thousand procedures performed worldwide since the first implant in 20021. Initial procedures were commonly associated with severe periprocedural complications and protracted hospital stays; however, device improvements and greater clinician experience have led to reductions in procedural times, and in the incidence and severity of complications. Reductions in sheath sizes and improved delivery systems have enabled safer device transfer via femoral access. Preoperatively, computed tomography scanning is now used routinely for access-site planning, valve sizing and coronary artery disease screening, thereby avoiding the use of intraoperative transoesophageal echocardiography, general anaesthesia and the need for invasive angiography2.

These improvements have naturally translated into reductions in length of hospital stay. For example, in a high-volume Canadian centre, between 2007 and 2012, the median length of stay reduced from seven to four days. With the introduction of an early discharge pathway, hospital stays reduced further: 150 (38.2%) patients from 2012 to 2014, in the early discharge group, had median length of stay of just one day (IQR 1-2), with no significant differences in the occurrence of death, stroke, bleeding or readmission within 30 days when compared to the standard discharge group3. Other studies have successfully implanted fast-track discharge pathways for transfemoral TAVI patients, reducing stays by approximately three days (7.2 to 4.3 and 6 to 3 days, respectively), with no effect on 30-day outcomes, including all-cause mortality and hospital readmission4,5.

There are several advantages associated with shorter hospital stays. Firstly, shorter stays are generally welcomed by patients, and it is well known that prolonged hospital stays are associated with an increased risk in the elderly. Secondly, substantial cost savings have been identified with early discharge – both to the patient and to the healthcare system – which is especially important in public healthcare systems including the United Kingdom’s National Health Service. In one cohort study, a total of 26 patients (21.7%) were discharged the same or next day and 39 (32.5%) between one and four days. Same/next day discharge led to cost savings of £3,091 (€3,523) and early discharge (>1-4 days) led to savings of £2,297 (€2,618) per patient when compared with late discharge6. Other healthcare systems have benefited: for example, in one centre in the USA, cost savings from the implementation of a minimalist TAVI approach decreased hospital stay and this was associated with a $10,000 mean cost reduction per patient7. More patients will become eligible for TAVI as indications expand, and thus streamlining the procedural pathway is important to maintain/increase availability. It is important that the implementation of an early discharge pathway is patient-centred and involves all members of the multidisciplinary team, since adoption of minimalist approaches does not always translate into reductions in length of hospital stay. For example, the increased use of local anaesthesia, reported in a large French registry (14% in 2010 to 59% in 2011), did not significantly reduce hospital length of stay8.

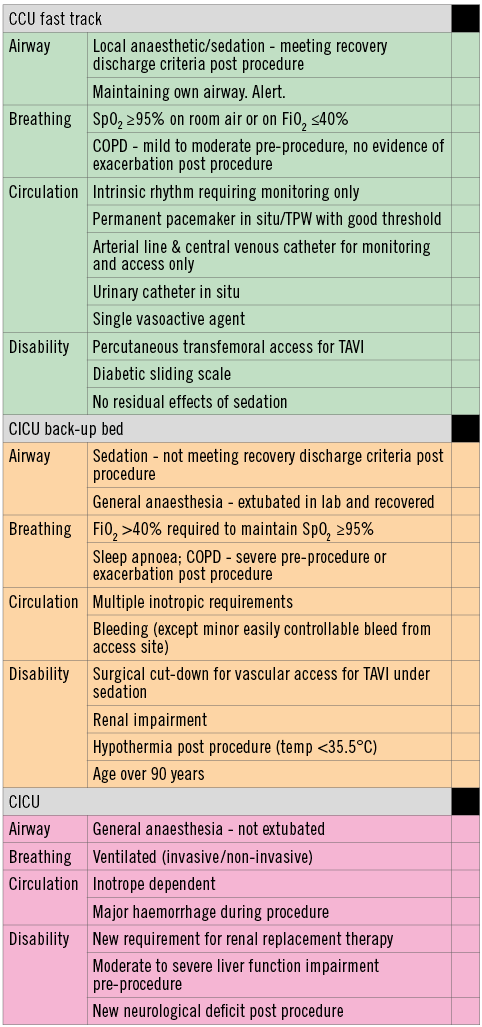

In our institution, since January 2016, we have adopted a “traffic light system” to triage patients as to whether they need intensive monitoring post procedure in a cardiac intensive care unit (CICU), or if they would be suitable for a fast-track coronary care unit (CCU) pathway leading to early discharge (Figure 1). Specific factors associated with suitability for early discharge include: 1) prior permanent pacemaker implantation; 2) femoral approach; 3) lack of periprocedural conduction disturbances; 4) conscious sedation; and 5) a good home support network. In addition, we now routinely insert a permanent pacemaker system at the end of the procedure, if advanced conduction disturbances develop intraoperatively, rather than adopt a “watch and wait” strategy with a temporary pacing wire. In contrast, we remove temporary wires at the end of the procedure if no conduction disturbances develop and the patient has a normal baseline ECG. Since implementation of the pathway (January 2016-April 2017), 33.3% of patients (n=44, mean age 79.9±8) were discharged home within 48 hours, and 88 patients (mean age 81.7±8) after a median four-day (IQR 2-7) length of stay. Patients in the early discharge group were more likely to be male (68.1% vs. 47.7%, p=0.026), have had a prior pacemaker inserted (15.8% vs. 3.5%, p=0.029), and the procedure performed via femoral access (100% vs. 83.0%, p=0.025) and under local anaesthesia/conscious sedation (95.5% vs. 79.3%, p=0.016). There were no differences in the primary endpoint of all-cause death and readmission within 30 days (5.68% [standard] vs. 2.27% [early]; p=0.375).

Figure 1. Traffic light system to triage patients post TAVI. High-risk patients with comorbidities including pre-existing severe renal and liver impairment or who undergo TAVI via transapical/subclavian access are triaged to the CICU for a higher level of periprocedural monitoring. In contrast, patients who undergo the procedure via local anaesthesia or sedation are generally fast tracked to the CCU in uncomplicated procedures. Patients requiring multiple inotropes or requiring oxygen (FiO2>40%) are triaged to the CICU for a period of stabilisation before transfer to the CCU. Patients are triaged to amber or red if a single parameter is present in that category. Courtesy of Angela Frame, Registered General Nurse, Imperial College NHS Healthcare Trust. CCU: coronary care unit; CICU: cardiac intensive care unit; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FiO2: fraction of inspired oxygen; SpO2: peripheral capillary oxygen saturation; TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation

Ongoing randomised studies (FAST TAVI: NCT02404467, and 3MTAVR: NCT02287662) are investigating the validity of early discharge protocols (<48 or <72 hours) but, as device iterations improve further and real-world experience with low-risk patients increases, is it possible that, similar to percutaneous coronary interventions, same-day discharge may become a reality9? Case reports have started to appear and, if healthier low-risk patients are eventually included in guideline recommendations, and device iterations continue to improve (smaller sheaths and devices to minimise complications), same-day discharge in certain patients may be possible10. It is, however, most probable that in the near future what we view as early discharge, presently <48 hours or next day, will become the gold standard, with delayed discharge left for the highest-risk patients.

At present, recent consensus guidelines do not mention discharge planning, or length of hospital stay and, therefore, currently, some experienced centres may be reluctant to change traditional perioperative management practices11. It is important that future guidelines address this area in order to streamline resources and maintain availability as, inevitably, indications for TAVI widen. Only with cost reduction will TAVI be an economically viable alternative to surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.