Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) can now be considered for any patient with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis (AS) who is set to receive an aortic valve replacement with a bioprosthesis1,2,3,4. In particular, the recent low-risk trials may dramatically increase the pool of eligible TAVI candidates, with estimates as high as 270,000 patients in Europe and North America5. The healthcare challenges for heart valve centres are significant. Different levels within a given TAVI programme require restructuring to cope with this changing supply/demand reality at reasonable cost and without concessions in quality. This includes: 1) stronger ties with referral hospitals to relocate preprocedural TAVI work-up outside of the implanting heart valve centres; 2) implementation of local anaesthesia/mild sedation protocols to minimise catheterisation laboratory occupation time; 3) avoidance of unnecessary time spent in intensive care units and general cardiology/cardiac surgery wards, and 4) harmonising institutional logistics.

This issue of EuroIntervention features the FAST-TAVI trial by Barbanti et al6 which evaluated an allegedly early discharge TAVI protocol.

FAST-TAVI was an observational, prospective study performed at 10 high-volume TAVI centres in Italy, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. The investigators proposed 13 variables after TAVI to define eligibility for safe early discharge with a 30-day composite primary endpoint of all-cause mortality, vascular access-related complications, permanent pacemaker implantation, stroke, rehospitalisation, kidney failure and major bleeding. Approximately 500 patients were included with a mean age >80 years and a EuroSCORE II of 5%. More than 80% underwent TAVI without general anaesthesia. More than 70% of patients were discharged within 72 hours. Low rates of mortality (1.1%), neurological events (1.7%) and need for pacemakers (7.3%) attest to the feasibility of an early discharge protocol. Geographical/national variations in discharge practice were notable. Logistic issues delayed early discharge in one third of patients and the 10% rehospitalisation rate justified a word of caution.

The FAST-TAVI trial included 502 “unselected” patients in 10 centres over a timespan of more than two years. “Unselected” then becomes a misnomer. This represented a rather highly selected set of patients undergoing balloon-expandable TAVI because we can assume that each of the 10 centres would have treated more than 50 patients in this time window and would have had more than one transcatheter valve platform at its disposal. Nevertheless, an early discharge policy underpinned by a number of criteria makes a lot of sense. In FAST-TAVI, all (selected) patients were apparently deemed eligible for early discharge prior to the TAVI procedure and were re-assessed after the procedure. In retrospect, this approach may have been overambitious and may explain the 10% rehospitalisation rate.

We should bear in mind that this was still an elderly population (age >80 years) with an elevated risk profile (EuroSCORE II 5%!). Reality will be different in low-risk patients. Indeed, in the recently published randomised trials evaluating TAVI in such patients with a mean age of 74 years, the average hospital stay was ≤3 days. The bar for early discharge could be higher, and we would therefore refer to early discharge as being within 48 hours. Furthermore, the term “early discharge” can be misleading: discharge home is not the same as discharge to (e.g.) the referral hospital or a nursing home. The destination for early discharge therefore determines the narrative and may require a variable approach. Patients could be discharged early (i.e., within 12 to 24 hours) to a referral hospital which has been involved in the preprocedural planning and informed about the procedure date. Indeed, the majority of the suggested criteria in FAST-TAVI may not preclude discharge to another hospital facility in the vast majority of TAVI patients. Kidney issues, blood transfusions, frailty indications, urinary or pulmonary tract infections and residual signs of congestion could be handled in any referring hospital. Of note, New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification proved helpful as a criterion prior to TAVI but it should be determined in stable circumstances and not as a day-to-day evaluation tool7. Social support and activities of daily living (ADL) independence seem a conditio sine qua non, at least for a home discharge. Intuitively, improved patient selection prior to the TAVI procedure could have reduced the risk of a premature hospital re-admission in FAST-TAVI.

Close collaboration with referring cardiologists may strengthen referring patterns and improve overall care. The Dutch leg of the FAST-TAVI trial seemed to have this network already in place, as was illustrated by the fact that more than half of the Dutch patient population was discharged (early) to the referral hospital. In this context, even conduction disorders might not be a real safety issue because continued rhythm monitoring is assured and the ability of pacemaker implantation is omnipresent.

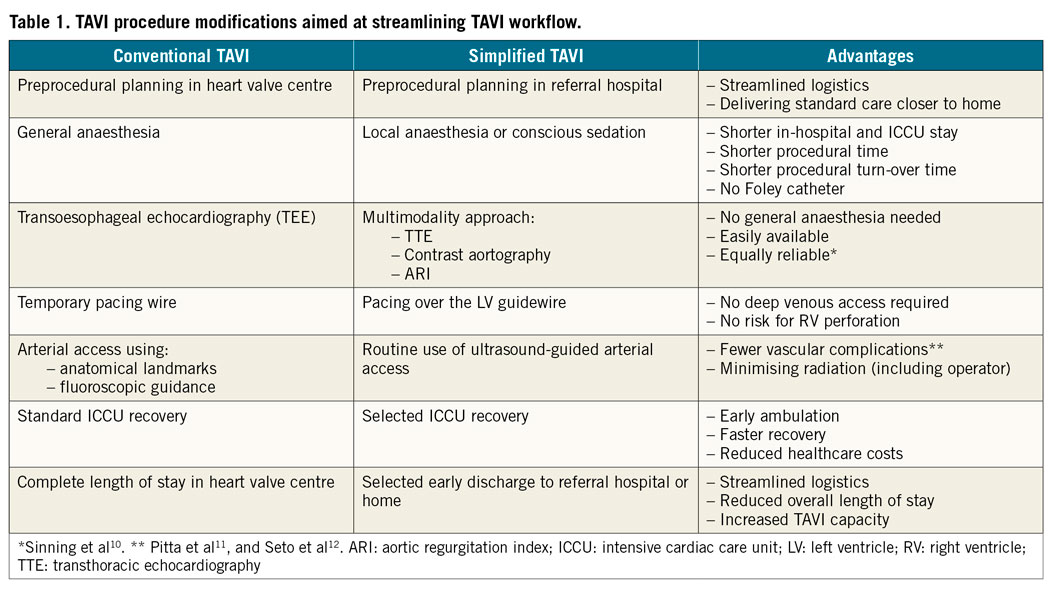

A major limitation of any early discharge programme, whether home or to another facility, is logistics. An expanding structural heart programme may conflict with an existing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) practice. It is therefore mandatory to implement those TAVI procedure modifications that expedite its execution (e.g., local anaesthesia, no Foley catheter, no temporary pacemaker). Table 1 illustrates TAVI procedure modifications in the Erasmus Medical Center to streamline TAVI procedure flow and increase daily TAVI capacity per operating room. Careful echocardiographic evaluation should complete any TAVI hospitalisation to confirm proper haemodynamic transcatheter valve performance and rule out accumulating pericardial effusion and excessive periprosthetic regurgitation that would require further invasive therapy. Importantly, in FAST-TAVI one third of prolonged hospitalisations were due to logistic restraints, a reality that is also recognised in our practice and is a principal target in our organisation for further improvement. It is anticipated that the workload for the echocardiography department will increase as the cardiology community in general embraces TAVI as the preferred therapy for all AS patients who need a bioprosthesis.

Of note, the FAST-TAVI trial featured only the balloon-expandable valve platform by Edwards Lifesciences (Irvine, CA, USA). Not every valve platform is suitable for an early discharge programme (e.g., because of conduction issues). Another valve platform to suit this purpose might be the supra-annular self-expanding ACURATE neo™ valve (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA), which demonstrated low rates of new pacemaker implantation (2.3%)8. This is under investigation in the POLESTAR trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03910751) driven by a hybrid assessment of baseline and periprocedural eligibility criteria.

In conclusion, the FAST-TAVI investigators should be commended for demonstrating the safety and feasibility of early home discharge after TAVI and illustrating further opportunities to improve the capacity of expert heart valve centres by involving referral hospitals in the post-procedure course. As a final note, we refer to a recent conclusion from the Transcatheter Valve Therapy (TVT) registry in the USA that TAVI volume does matter and that there is an inverse volume-mortality association9. Clearly, TAVI is safer in the hands of the most experienced. Let us therefore support the development of high-volume TAVI programmes with experienced operators and not fall for the premature call to open more TAVI centres. This is more a call to the creativity of existing heart valve centres.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.