Since the introduction of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) into clinical practice, the treatment of aortic valve disease has changed dramatically. TAVI has become the treatment of choice for patients with symptomatic severe aortic valve stenosis (AS) who are at increased risk for conventional cardiac surgery. The rapid expansion of TAVI has been based upon robust clinical evidence derived from randomised controlled trials and large-scale international and national registries. Over the past decade, TAVI has evolved into a safe and effective procedure with predictable and reproducible outcomes. As a consequence, TAVI technology is increasingly used to treat patients with a lower risk profile, and the volume of TAVI now exceeds the volume of isolated surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) in some countries1,2. It may be anticipated that, in the near future, the majority of patients with symptomatic severe AS will undergo TAVI as first-line therapy, regardless of their age and risk profile. This raises the question about the future role of SAVR in the era of catheter-based therapies.

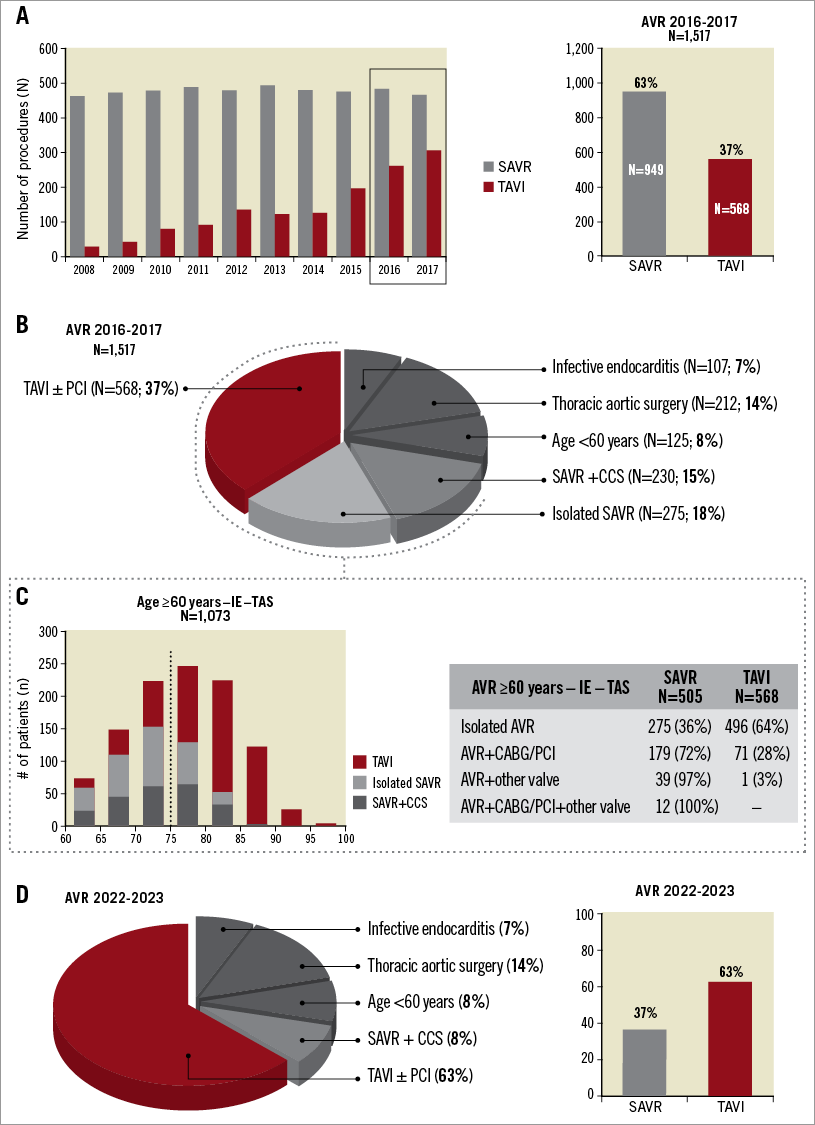

Since TAVI was introduced in East Denmark in 2007, this therapy has seen an average annual growth of more than 35%. During the same period, SAVR volumes remained stable (Figure 1A). This increase in AVR can be ascribed to an ageing population in Western countries as well as a lower threshold to treat AS patients at high surgical risk by means of TAVI. Similar patterns have been observed in other Western countries, while even a 10-20% decline in SAVR volumes has been reported in Germany1.

Figure 1. Current status and future perspectives for transcatheter and surgical aortic valve replacement. A) Evolution of SAVR and TAVI over the past decade in East Denmark. B) AVR in 2016-2017. C) Age distribution and concomitant procedures in TAVI-eligible patients. D) Projection of AVR in 2022-2023. AVR: aortic valve replacement; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft surgery; CCS: concomitant cardiac surgery; IE: infective endocarditis; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SAVR: surgical aortic valve replacement; TAS: thoracic aortic surgery; TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation

In recent years, TAVI technology is also increasingly used to treat patients with a lower risk profile; this practice is supported by results from the NOTION, PARTNER-II and SURTAVI trials indicating that TAVI is a viable option for patients with a low to intermediate surgical risk profile3-5. In the 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease, TAVI has become the default therapy to treat AS patients aged 75 years or more, especially if TAVI can be performed by transfemoral (TF) approach6. In line with German registry-based data published in 20162, approximately 2/3 of all patients with isolated severe AS are currently treated by TAVI in East Denmark (Figure 1B). This raises the question as to whether SAVR will soon become redundant or obsolete.

When considering all AVR procedures performed in East Denmark (population: 2.7 million) in the period 2016 to 2017, it can be determined that 568 patients (37%) were treated by TAVI, while 949 patients (63%) underwent SAVR (Figure 1A). As indicated in Figure 1B, a significant number of patients will (most likely) also require cardiac surgery in the future, due to the presence of infectious endocarditis (7%), need for aortic root replacement due to aortic aneurysm/dissection (14%), or the indication for a mechanical aortic valve prosthesis in younger patients. As a consequence, SAVR will remain the preferred treatment for at least 30% of all patients requiring AVR.

For those patients who are theoretically eligible for TAVI (Figure 1B, Figure 1C; indicated by dotted line; n=1,073), 568 patients (53%) were treated by TAVI whereas 505 patients (47%) were treated by SAVR during the period 2016 to 2017. Clearly, there are multiple reasons why these patients were referred for SAVR. First of all, SAVR is still the preferred therapy for patients aged less than 75 years. This is mainly because robust clinical evidence is missing for this particular patient population with longer life expectancy. In addition, concerns about long-term valve durability and coronary access in case of (future) valve-in-valve procedures have been raised7. For this reason, the NOTION-2 trial was designed, comparing TAVI with SAVR in AS patients aged ≤75 years and with an STS surgical risk score ≤4% (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02825134). A second important reason for referral to SAVR is the need for concomitant cardiac surgery. In most cases, it concerns diffuse coronary artery disease (CAD) judged to favour treatment by coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery (n=179; 17%). In other patients, it concerns concomitant cardiac valve disease (n=51; 5%) (Figure 1C).

The current practice (2018) in East Denmark is to treat patients aged 75 years or more with TAVI, except in case of important concomitant CAD or other valve disease (Figure 1C). However, this “cut-off” age is decreasing and TAVI may be foreseen to replace SAVR in uncomplicated AVR when a bioprosthetic aortic valve is preferred. Given the good clinical outcomes obtained with current TAVI devices, the role for isolated SAVR is likely to decrease over the coming years (Figure 1D). Potential limitations for TAVI in isolated aortic valve disease may be a bicuspid valve anatomy (which is more present in younger patients), pure native aortic valve regurgitation, and too large an aortic annulus size for transcatheter heart valves. However, technological improvements have not come to a halt yet, and it can be expected that dedicated TAVI devices for these conditions will be available soon.

When considering the group of patients with concomitant CAD, the majority of patients are currently still treated by SAVR plus CABG (72%) (Figure 1C). However, with the expectation of treating ever younger patients with TAVI and an increasing experience with complex percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) – including a rapidly growing toolbox to treat chronic total occlusions – it may not be unrealistic to predict that a significant proportion of these patients will be treated by TAVI plus PCI in the future (Figure 1D).

In conclusion, further growth of TAVI can still be expected, even in those countries which already have a high TAVI adoption rate. Even though TAVI has become a mature technology over the past decade, some new dedicated TAVI devices are still warranted to treat specific patient subgroups. Importantly, SAVR will not become redundant or obsolete. Even if TAVI is used to treat all patients with isolated aortic valve disease as well as aortic valve disease in combination with CAD, aortic valve surgery will still be needed in one third of all patients requiring AVR (Figure 1D). However, the cardiac surgeon will face more complex aortic valve pathology, comprising cases of infectious endocarditis, and patients needing aortic root or other concomitant cardiac surgery. This supports the centralisation of these services within centres of excellence, both for TAVI and for cardiac surgery, which could provide best clinical practice, research, and education.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.