The term “complex” is sometimes abused and misused in the field of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). This is because “complex” is first of all a relative rather than a truly absolute term: what is difficult for one interventionalist may not be so for another. Essentially, what you know how to do is easy, and what you don’t is complex. Shigeru Saito, while accepting the -Geoffrey O. Hartzler Master Clinical Operator Award at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics conference 2019, asked about his zen attitude during complex PCI cases, said: “My secret? I never do anything I cannot do and I always do something I can do”.

What makes PCI complex?

The definition of PCI complexity is not universally standardised. In the USA, the “CHIP” acronym has been proposed1. CHIP stands for “complex, high-risk and indicated patients” with coronary artery disease (CAD) needing revascularisation. This subset includes aspects of complexity associated with patients, coronary anatomy and/or haemodynamic characteristics. More and more interventionalists qualify themselves as CHIP experts in international conferences. In Europe, the current counterparts of CHIP are a number of groups that separately tackle different aspects of CAD complexity, including PCI of bifurcations (European Bifurcation Club), chronic total occlusions (EuroCTO club) and calcified lesions (Euro4C).

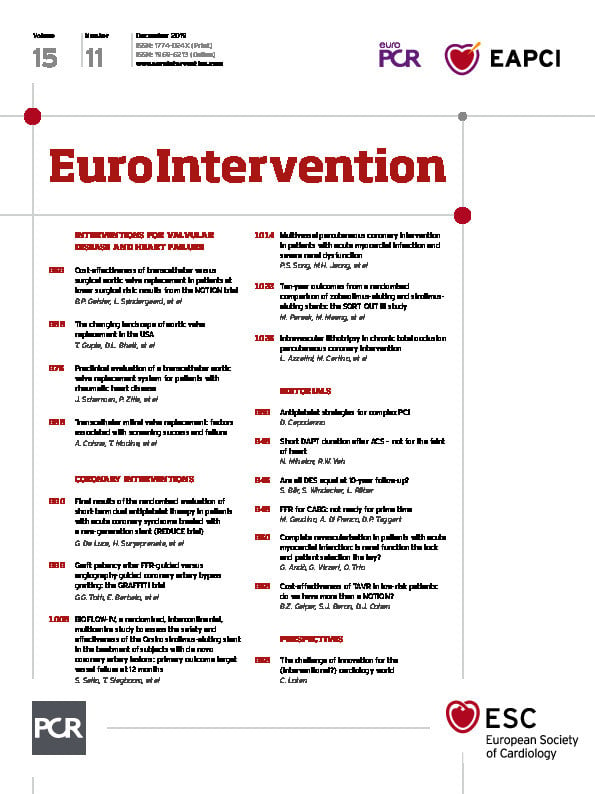

When it comes to defining the complexity of PCI as a means of distinguishing patients at lower or higher risk of thrombotic or ischaemic complications, the definition proposed by Giustino and colleagues is also experiencing ever-increasing success2. This is because of its intuitive simplicity and plausibility. In their studies, many investigators now make common reference to the so-called “Giustino’s criteria” as it relates to identifying patients undergoing complex PCI3,4. Giustino’s criteria include PCI with three vessels treated, at least three stents implanted, at least three lesions treated, a bifurcation with at least two stents implanted, a total stent length of 60 mm or longer, and/or the successful treatment of a chronic total occlusion (Figure 1),2.

Figure 1. Giustino’s criteria. Illustration of criteria of complexity and risk for ischaemic and/or thrombotic complications after percutaneous coronary intervention2.

The complexity of PCI sometimes also equates with the challenge of coupling devices with antithrombotic drugs5. For example, appropriate decisions on antiplatelet therapy become a complex undertaking in patients who are at high risk of bleeding (HBR). A recent initiative from the Academic Research Consortium (ARC) for HBR patients led to the publication of a consensus document on standardised definitions of HBR that sets out a number of major and minor criteria in order to anticipate a one-year risk of Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) type 3 or 5 bleeding of 4% or greater, or a risk of intracranial haemorrhage of 1% or greater with post-PCI dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT)6.

Against this background, what is the best antiplatelet strategy for complex PCI patients in view of the HBR experienced by some? Should we fear the ischaemic risk more than the bleeding risk or vice versa? These are current controversies in a moving field.

Which antiplatelets for complex PCI?

The 2018 guidelines for myocardial revascularisation from the European Society of Cardiology state that the oral P2Y12 inhibitors prasugrel or ticagrelor “may be considered in specific high-risk situations of elective stenting”7. This implies the potential use of the two drugs instead of clopidogrel for patients who do not have an acute coronary syndrome, but who need a complex PCI. However, the level of evidence for this class IIb recommendation is only C. Certainly, it would be valuable to have randomised evidence in support of DAPT with more potent P2Y12 inhibition than clopidogrel in the setting of elective complex interventions. Elective patients tend to bleed less than those who undergo PCI in emergent settings, which may alter the risk-benefit equation.

Cangrelor has entered the armamentarium of many cath labs worldwide. With its fast onset and offset of action, an intravenous formulation of a P2Y12 inhibitor is something that we did not have before. In the CHAMPION PHOENIX trial, cangrelor reduced ischaemic events at 48 hours compared with a loading dose of clopidogrel in patients undergoing PCI8. A large blinded angiographic core laboratory analysis of 13,418 target lesions from 10,854 patients included in CHAMPION PHOENIX concluded that periprocedural ischaemic events after PCI depend on the number of treated high-risk target lesion features (i.e., bifurcation, left main, thrombus, angulated, tortuous, eccentric, calcified, long, or multi-lesion treatment)9. As such, because cangrelor was found to reduce events irrespective of clinical presentation and baseline lesion complexity, PCI patients with a complex coronary anatomy may derive the greatest benefit relative to risk. How this strategy compares with the use of prasugrel or ticagrelor, however, is unknown.

Which DAPT duration for complex PCI?

The European guidelines set two standards for DAPT duration after PCI – six months in elective presentations and 12 months in acute coronary syndromes10. However, this term can vary based on PCI complexity (>6 or >12 months, respectively) and HBR presentation (3 or 6 months, respectively). In a pooled patient-level meta-analysis of 9,577 patients from six randomised controlled trials investigating DAPT durations after PCI, patients were stratified into those undergoing complex or non-complex PCI based on Giustino’s criteria2. Ischaemic events were reduced significantly by longer DAPT compared with shorter DAPT in patients undergoing complex PCI, but not in those undergoing non-complex PCI (p for interaction=0.01). Conversely, the risk of bleeding was higher in both subsets (p for interaction=0.96). The authors concluded that procedural complexity is an important parameter to take into account in tailoring upfront duration of DAPT.

A substudy of the DAPT trial from Yeh et al, using a different definition of PCI complexity, concluded that the benefits of extending DAPT are similar in subjects with and without complex lesions11. Also, a high DAPT score identified patients experiencing the most benefit from extended treatment among those with and without complex PCI. Again, because patients undergoing complex PCI have a higher risk of future events, the relative merits of extended DAPT may be magnified in this cohort. However, how is the risk of bleeding factored into this equation? This question was recently addressed by another study from Costa et al, encompassing 14,963 patients from eight trials of DAPT duration. The study used Giustino’s criteria to define complex PCI and a PRECISE-DAPT score of 25 or greater to define HBR3. In non-HBR patients, long-term DAPT reduced ischaemic events in both complex and non-complex PCI. Nevertheless, this was not the case in HBR patients, the only group where the risk of bleeding was increased, regardless of PCI complexity. The implication of these findings is that patients undergoing complex PCI benefit from DAPT prolongation only if they are not HBR. The authors concluded that “when concordant, bleeding, more than ischaemic risk, should inform decision making on the duration of DAPT”.

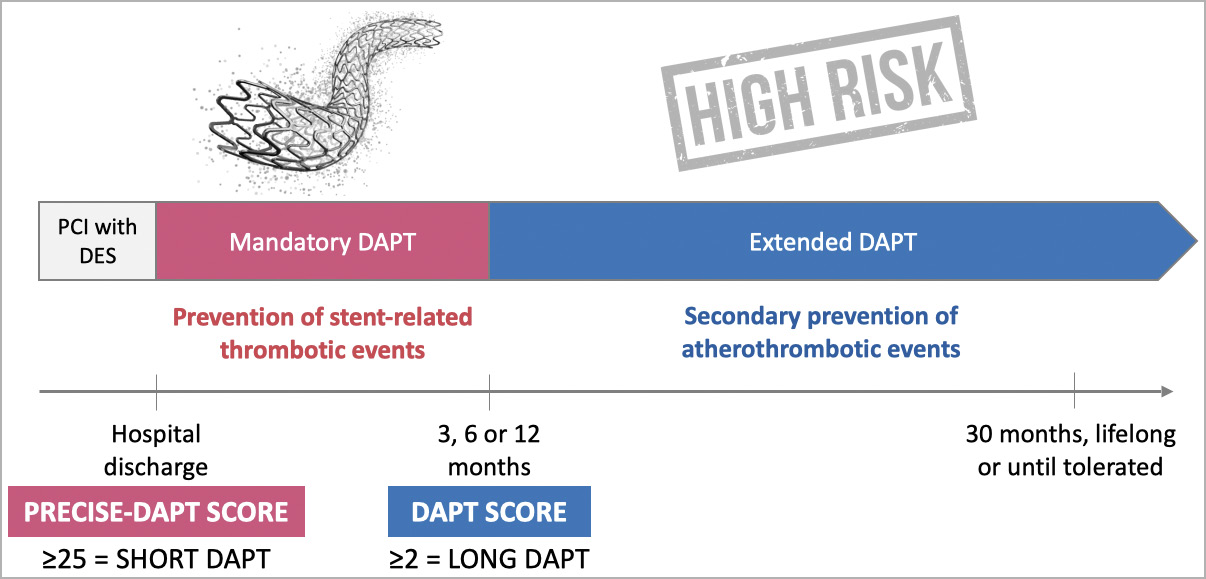

In summary, after complex PCI with DES, it is appropriate to anticipate the risk of bleeding (e.g., with the PRECISE-DAPT score) to inform decisions regarding the duration of DAPT (Figure 2). To prevent stent-related thrombotic events, the patients will start a period of “mandatory DAPT” that may last 3, 6 or 12 months depending on PCI complexity and clinical presentation. Subsequently, considerations on further DAPT extension will depend on the bleeding outcomes of the mandatory period, on top of consideration regarding PCI complexity, risk stratification (e.g., with the DAPT score) and the opportunity for secondary prevention of atherothrombotic events. The 2019 guidelines for chronic coronary syndromes make a case for “intensified antithrombotic therapy” (i.e., another antithrombotic drug on top of aspirin) in appropriate scenarios12.

Figure 2. Protecting stents ≠ protecting patients. After percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with a drug-eluting stent (DES), a period of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) is mandated to ensure low risk of thrombosis while the stent struts are covered by endothelium. This term of DAPT must be balanced against the risk of bleeding, which may be predicted at discharge by the use of scoring tools such as the PRECISE-DAPT score. After the mandatory period of DAPT, if no high bleeding risk emerges, there is an opportunity for extending the DAPT further depending on the residual risk of ischaemia. The latter may be estimated with the use of scoring tools such as the DAPT score, or based on considerations about PCI complexity, including Giustino’s criteria illustrated in Figure 1.

New directions

Strategies that look for the sweet spot between ischaemic and bleeding prevention include the use of potent P2Y12 inhibitors without aspirin after a short period of DAPT. Complex PCI patients are widely represented in some of these investigations. In a post hoc analysis of the large GLOBAL LEADERS trial, ticagrelor monotherapy after one month of DAPT was found to provide a net benefit compared with standard therapy in patients fulfilling Giustino’s criteria, with significant interaction p-values versus non-complex PCI for ischaemic endpoints but not for bleeding endpoints4. In view of the neutral results of the main trial, these findings are only hypothesis-generating. In the TWILIGHT trial, inclusion criteria were enriched by criteria of angiographic complexity, finally encompassing a population that is relevant to the subject13. TWILIGHT concluded that, after two months of DAPT, ticagrelor monotherapy is associated with a lower incidence of clinically relevant bleeding than ticagrelor plus aspirin, with no higher risk of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke.

Antithrombotic therapy and complex PCI: final considerations

The evidence reviewed above collectively suggests a number of considerations that are relevant to daily practice in dealing with complex PCI. Firstly, ischaemic events increase progressively with the number of high-risk angiographic features. Prasugrel and ticagrelor are recommended for acute coronary syndromes and may be considered for elective complex PCI. Cangrelor consistently reduces periprocedural events regardless of angiographic complexity. Secondly, complex PCI suggests an opportunity for extending DAPT beyond the period mandated by clinical guidelines, but HBR should inform decision making on DAPT duration, even in complex PCI patients. The PRECISE-DAPT and DAPT scores are useful stratification tools in both complex and non-complex PCI patients. Finally, emerging strategies to optimise the risk-benefit balance of antithrombotic therapy for complex patients, including the “less is more” principle of replacing DAPT with the use of a single potent P2Y12 inhibitor, have shown promise and may warrant further investigation in this setting.