Abstract

Aims: Percutaneous revascularisation triage has not been evaluated in randomised controlled trials of patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes (NSTE-ACS) and multivessel disease. As a result, current guidelines are not available. The objective of our meta-analysis was to investigate the use of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in culprit and non-culprit vessels.

Methods and results: We undertook a meta-analysis of controlled studies where patients were assigned to multivessel PCI or culprit vessel PCI. Summary odds ratios (OR) for all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, unplanned revascularisation and major adverse cardiac events (MACE) were calculated using random- or fixed-effect models. Six registry studies (n=5,414) were included in this meta-analysis. There was no difference in the rate of mortality (OR, 0.85; 95% CI: 0.70 to 1.04; p=0.114) or myocardial infarction (OR, 0.75; 95% CI: 0.43 to 1.32; p=0.319) between the two treatment groups. Multivessel PCI may decrease long-term MACE (OR, 0.69; 95% CI: 0.51 to 0.93; p=0.015) and unplanned revascularisation (OR, 0.64; 95% CI: 0.45 to 93; p=0.018) compared with culprit vessel PCI.

Conclusions: No significant difference was demonstrated in the long-term risk of myocardial infarction and mortality between multivessel PCI and culprit vessel PCI. Therefore, multivessel PCI may be a safe and reasonable option for NSTE-ACS patients with multivessel disease.

Introduction

Multivessel disease is seen in approximately half of patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes (NSTE-ACS) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)1,2. However, multivessel PCI on both culprit and non-culprit vessels in NSTE-ACS patients with multivessel disease is a controversial issue. A registry study demonstrated that multivessel PCI might be associated with a lower success rate and a higher risk of myocardial infarction (MI)3. It is not clear whether PCI in non-culprit vessels will prevent adverse cardiac events in the future. Management of culprit vessels with PCI is usually the preferred choice in patients with multivessel disease4.

The long-term outcomes of multivessel PCI versus culprit vessel PCI from small registries are variable and none of the studies was powered to detect a difference in clinical endpoints. We performed a meta-analysis of studies comparing the outcomes of culprit and multivessel PCI in patients with NSTE-ACS and multivessel disease.

Methods

LITERATURE SEARCH

We performed an electronic literature search from the beginning to January 2, 2014 in MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, Embase, ISI Web of Knowledge and Google Scholar, using the term “multivessel” paired with the following: “acute coronary syndrome”, “myocardial infarction”, “revascularisation”, “angioplasty”, “stents”, “invasive”, “culprit” “single-vessel”, “single vessel” or “percutaneous coronary intervention”. Abstract lists from the scientific meetings of the American College of Cardiology, the European Society of Cardiology, and Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics, as well as published review articles, editorials, and internet-based sources of information on studies of interest, including www.tctmd.com and www.theheart.org, were also reviewed.

STUDY SELECTION

Both prospective and retrospective studies were considered for inclusion. Studies were selected if the long-term outcome of multivessel PCI and culprit vessel PCI was evaluated in NSTE-ACS patients with multivessel disease. Studies investigating PCI in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients with multivessel disease were not included. In addition, studies comparing complete versus incomplete revascularisation in patients with multivessel disease were excluded. Publications with follow-up of less than six months were also excluded.

Data extraction

All literature searches were independently reviewed by two authors (Qiao Y and Li WJ) to identify relevant studies which met the inclusion criteria. Disparities were resolved by discussion. Information was extracted using a standardised protocol and reporting form with regard to the study design, indicators of quality, baseline clinical characteristics, procedural details, and clinical and safety outcomes. For studies which reported results at multiple time points, the data from the longest follow-up time were included in the analysis. Authors were contacted in case of incomplete or unclear data.

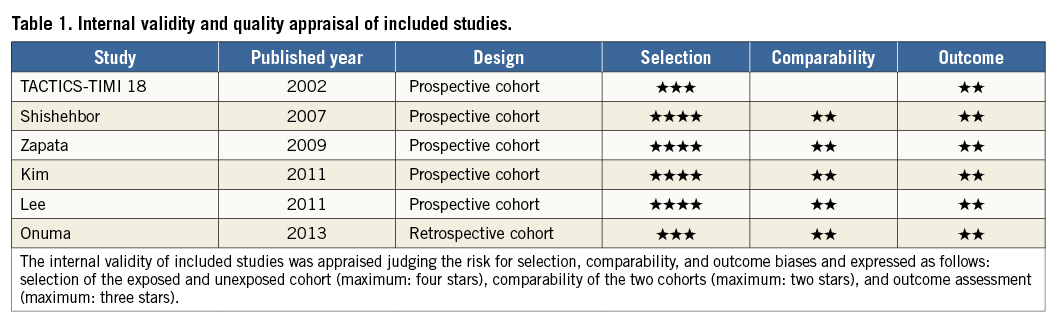

INTERNAL VALIDITY AND QUALITY APPRAISAL

The internal validity and quality of the included studies were appraised according to Newcastle-Ottawa Scales (NOS) for cohort studies, by two independent reviewers aware of the study origin and journal, with divergences resolved after consensus. This quality assessment tool consists of three domains, including selection of the exposed and unexposed cohort (maximum: four stars), comparability of the two cohorts (maximum: two stars), and outcome assessment (maximum: three stars)5,6 (Table 1).

DEFINITIONS AND ENDPOINTS

Multivessel disease was defined as a significant stenosis in ≥2 major epicardial vessels in all studies, and significant stenosis was defined as >50% stenosis in all the studies except for one, which used 70%7. The endpoints of interest were all-cause mortality and major adverse cardiac events (MACE), which included myocardial infarction, unplanned revascularisation and mortality. Long term was defined as more than six months. Unless otherwise specified, mortality included both cardiac and non-cardiac death. MI, multivessel disease and culprit lesion were defined as reported in the studies.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Results from each trial were organised into a two by two table to permit calculation of effect sizes for multivessel PCI and culprit vessel PCI. All data were pooled at the study level, because patient level data were not available. Such pooling has previously been demonstrated to be valid for estimating pooled treatment effect8. Statistical heterogeneity of treatment effects between studies was formally tested using Cochran’s test (p<0.100) and the I2 statistic. We considered I2 >50% to indicate significant heterogeneity between studies9. Fixed-effect models were used to calculate across-study odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals of primary and secondary endpoints, if there was no significant heterogeneity, or for random-effect models10. The Begg and Mazumdar adjusted rank correlation test with funnel plot was performed to test for publication bias11. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata software version 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

SEARCH RESULTS

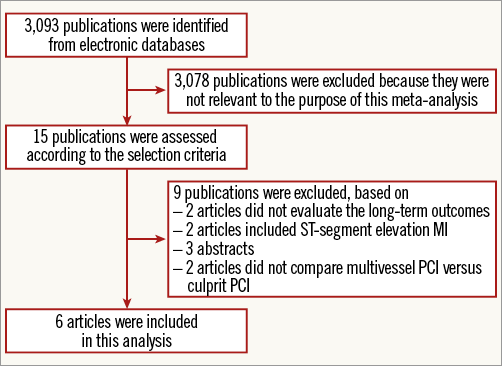

A total of 3,093 publications were identified manually, 3,078 of which were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Two articles were excluded because they did not evaluate the long-term outcome3,12. Two additional articles were not included because ST-segment elevation MI was included in the analysis13,14. Another article which did not compare the two treatment groups was also excluded15,16. Three abstracts were excluded because the baseline data and long-term follow-up were not available. Six controlled studies met the inclusion criteria for comparing culprit vessel PCI with multivessel PCI in NSTE-ACS patients with multivessel disease (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the inclusion and exclusion process used in the meta-analysis.

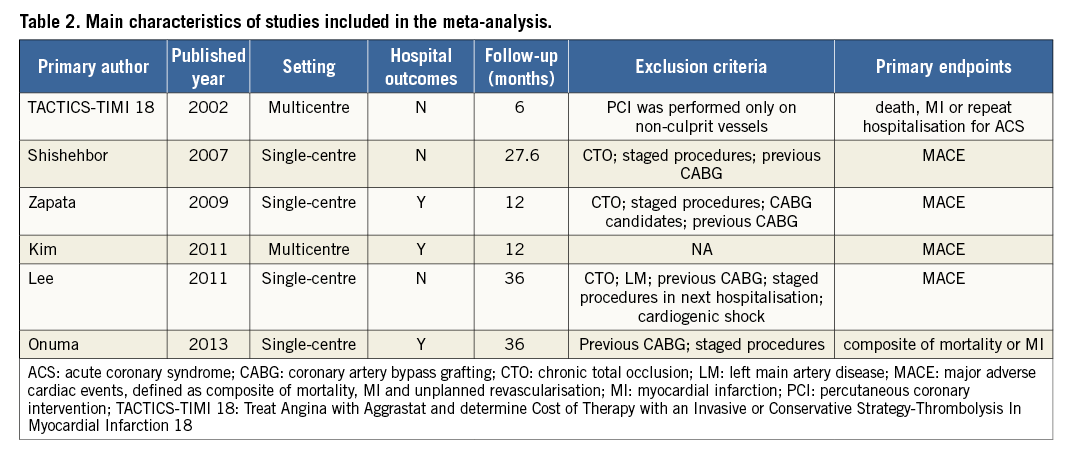

DESCRIPTION OF INCLUDED STUDIES

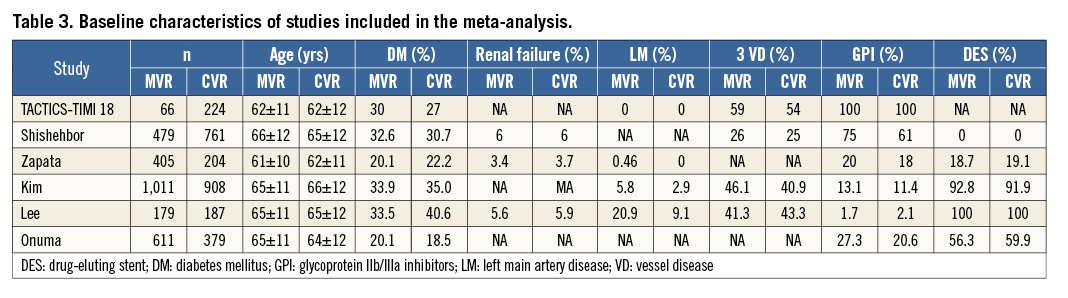

Six controlled studies with 5,414 subjects were included in our meta-analysis7,17-21. Long-term follow-up was available in all studies. The main characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 2. The baseline characteristics of the studies are listed in Table 3. Multivessel PCI was described as performing culprit and non-culprit vessel PCI during the same index hospitalisation.

CLINICAL ENDPOINTS

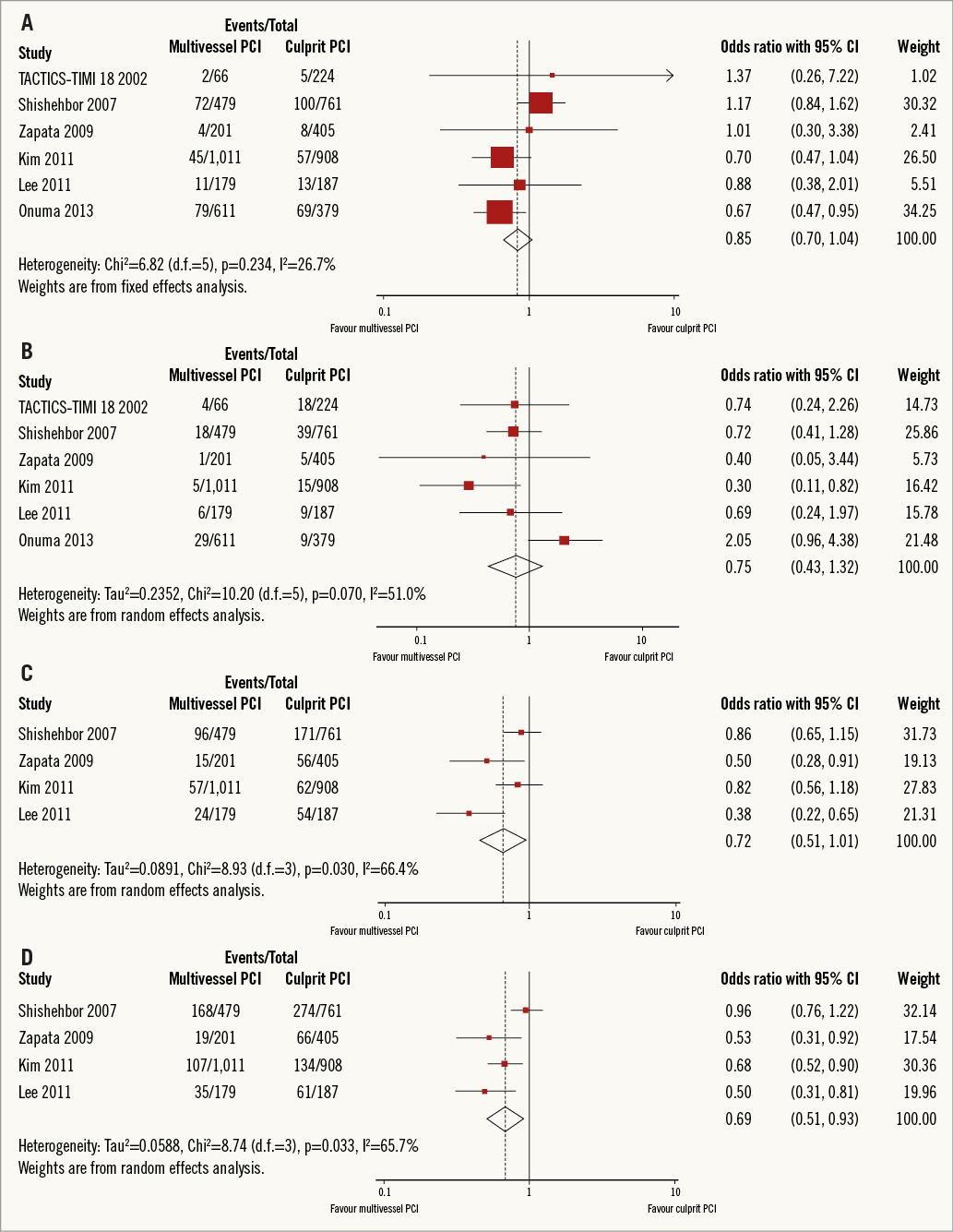

Long-term mortality in the studies ranged from 2.0% to 18.3% in the multivessel PCI arm, and from 2.0% to 13.1% in the culprit vessel PCI arm (no significant difference; OR, 0.85; 95% CI: 0.70 to 1.04; p=0.114) (Figure 2A), which was calculated with a fixed-effect model because no significant heterogeneity was observed across studies (I2=26.7%, p=0.234).

Figure 2. Forest plots comparing multivessel PCI vs. culprit vessel PCI outcome. A) Mortality. B) Myocardial infarction. C) Unplanned revascularisation. D) Major adverse cardiac events (MACE). CI: confidence interval; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; Weight: statistical weight (an indirect estimate of study precision and impact of overall pooled estimates on the single study result).

The incidence of myocardial infarction ranged from 0.5% to 6.1% in the multivessel PCI arm, and from 1.2% to 8.0% in the culprit vessel PCI arm. Multivessel PCI did not significantly decrease the long-term risk of myocardial infarction (OR, 0.75; 95% CI: 0.43 to 1.32; p=0.319) (Figure 2B) compared to culprit vessel PCI. This calculation was performed using a random-effect model because of significant heterogeneity across studies (I2=51%, p=0.070).

The incidence of unplanned revascularisation ranged from 5.6% to 20.0% in the multivessel PCI arm, and from 6.8% to 22.5% in the culprit vessel PCI arm. Two studies were not included in this analysis because data on non-target vessel revascularisation were not available17,21. Multivessel PCI was associated with a significantly decreased risk of unplanned revascularisation (OR, 0.64; 95% CI: 0.45 to 0.93; p=0.018) (Figure 2C). This calculation was performed using a random-effect model because of significant heterogeneity across studies (I2=66.4%, p=0.030).

Major adverse cardiac events occurred in 9.5% to 35.1% of patients in the multivessel PCI arm, and 14.8% to 36.0% of patients in the culprit vessel PCI arm. Two studies were not included in this analysis because data on MACE were not available17,21. Multivessel PCI significantly reduced the long-term risk of MACE (OR, 0.69; 95% CI: 0.51 to 0.93; p=0.015) (Figure 2D) compared with culprit vessel PCI. This calculation was performed using a random-effect model because of significant heterogeneity of treatment effects across studies (I2=65.7%, p=0.033).

SMALL STUDY EFFECTS

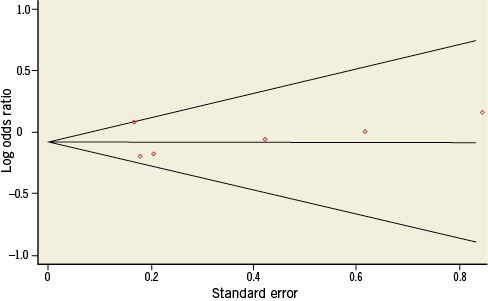

There was no evidence of small study effects for any of the endpoints studied. The Begg and Mazumdar test suggested no evidence of small study effects for major adverse cardiac events (p=0.452) or any of the other endpoints (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Funnel plot for the long-term risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE).

Discussion

The main finding of this meta-analysis was that multivessel PCI was associated with a 36% reduction in unplanned revascularisation and a 31% reduction in the risk of MACE at long-term follow-up compared with culprit vessel PCI. No difference was observed in the risk of all-cause mortality or MI.

Myocardial revascularisation for NSTE-ACS relieves symptoms, shortens hospital stay, and improves prognosis. It has become the preferred choice, especially in high-risk patients. About 40%~60% of NSTE-ACS patients have multivessel disease, which is associated with a higher risk of serious cardiac events22-24. It is not clear whether stenting non-culprit lesions after culprit lesion PCI is beneficial in preventing future adverse cardiac events. There are concerns regarding the potential risks of contrast-induced nephropathy and periprocedural MI when performing multivessel PCI13. Patients presenting with ACS have widespread inflammation and are in a prothrombotic state. Hence, additional stenting may further increase the risk of stent thrombosis25. However, no randomised trial has been conducted to compare the safety and efficacy of multivessel PCI involving suitable non-culprit vessels with that of culprit vessel PCI.

The National Cardiovascular Database Registry3 and EHS-PCI registry12 reported that multivessel PCI significantly increased the risk of in-hospital MI. However, a propensity matched study demonstrated that the composite of death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and all-cause mortality was not different with multivessel and culprit vessel PCI at 2.3 years18. Similar results were also reported in another propensity matched study which demonstrated that multivessel PCI could reduce all-cause mortality, compared to single-vessel PCI, at three-year follow-up18. Another prospective study demonstrated that multivessel PCI had less risk of MI than culprit vessel PCI at one-year follow-up19. The previously reported findings are similar to our study, where there was no difference in the risk of MI or all-cause mortality with multivessel and culprit vessel PCI.

In deciding the revascularisation strategies for performing culprit only or multivessel PCI, operators should consider important clinical characteristics including age, comorbidity, lesion characteristics, renal function, haemodynamics, costs, local reimbursement rules, time point and duration of the procedure, etc. However, the decision to perform multivessel PCI was made by the operators, and detailed information was not available in the studies included in our meta-analysis. Furthermore, cardiogenic shock in patients with multivessel disease is associated with increased hospital mortality26,27. The European Society of Cardiology guidelines28 recommend attempting multivessel PCI in selected patients with multiple critical lesions in the setting of cardiogenic shock. Only one study20 excluded cardiogenic shock patients, and other studies did not provide cardiogenic shock-related data in the included studies. All these factors may have influenced the final outcome of the meta-analysis because of the inherent defects of the studies included.

Multivessel PCI has been associated with lower composite endpoints, such as risk of death, myocardial infarction, or unplanned revascularisation, than culprit vessel PCI18. This is mainly because of the lower incidence of unplanned revascularisation found with multivessel intervention. This benefit may be due to better relief of ischaemia due to stenting non-culprit vessels. No significant difference was found in the rate of unplanned revascularisation or MACE in a recent retrospective study because data on non-target vessel revascularisation were not collected21. According to our meta-analysis, multivessel PCI significantly reduced the risk of unplanned revascularisation and MACE. Repeat revascularisation after the index hospitalisation mainly referred to unplanned revascularisation, which meant to all non-target vessel revascularisation and target vessel revascularisation, except for one study21 which only referred to target vessel revascularisation because the data on non-target vessel revascularisation were unavailable. Moreover, detailed information about unplanned revascularisations is unknown, as to when and why repeat revascularisations were performed, whether they were driven by ischaemia or angiography. The absence of all this information was a limitation to evaluating unplanned revascularisations and MACE between culprit PCI and multivessel PCI. Nevertheless, all the studies included in our meta-analysis were conducted in the era of first-generation drug-eluting stents (DES) and bare metal stents. Second-generation drug-eluting stents have been associated with a reduced risk of target vessel revascularisation, stent thrombosis and MI29,30, which will further improve the clinical outcome of multivessel PCI.

These results corroborate earlier observational studies demonstrating no major difference in the risk of all-cause mortality and MI in NSTE-ACS patients with multivessel disease treated with multivessel PCI and culprit vessel PCI. Moreover, multivessel PCI may be associated with significant reductions in MACE, mainly owing to concordant reductions in unplanned revascularisations. This study supports the use of multivessel PCI during the index hospitalisation as a safe option. Whether these effects apply to different patient subgroups and types of drug-eluting stent merits further investigation in a randomised trial.

Limitations

This meta-analysis included both prospective and retrospective studies because no randomised trial was available. Study-level meta-analysis cannot overcome the inherent limitations of individual trials by pooling treatment effect estimates to generate a single best estimate. We could not pool multivariable adjusted risk estimates because only three studies were adjusted with a uniform adjusted model, which may also reduce the power of the meta-analysis. The inclusion of studies with different designs introduced heterogeneity into the results. Heterogeneity could be related to the different study criteria used for treatment and the different endpoint definitions. In most studies, PCI strategy was influenced by patient characteristics, which could not be corrected for. There were limited data regarding haemodynamics in the included studies, so subgroup analyses could not be performed. The confounding factors could not be adjusted because the adjusted model in individual studies varied, which may lead to bias. The results and conclusions should be interpreted with these limitations in mind.

Conclusions

No significant difference was demonstrated in the long-term risk of mortality and MI between multivessel PCI and culprit PCI in NSTE-ACS patients with multivessel disease. Moreover, multivessel PCI may reduce the risk of unplanned revascularisation and MACE as compared to culprit vessel PCI. Multivessel PCI may be a reasonable option in multivessel disease patients presenting with NSTE-ACS. Additional studies are needed to identify the optimal treatment strategy for NSTE-ACS patients with multivessel disease.

| Impact on daily practice It is difficult to make a choice between multivessel PCI and culprit vessel PCI for NSTE-ACS with multivessel disease because of a lack of sufficient evidence. Our study has shown that multivessel PCI is feasible and safe with no increase in the risk of myocardial infarction or death. Hence, in daily clinical practice, multivessel PCI is an option to consider in this subset of patients. |

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.