Diabetes mellitus is a growing medical concern. Among patients with coronary artery disease and those with myocardial infarction, the reported prevalence of diabetes ranges between 20 and 40%.

Those patients with recognised diabetes mellitus do not, however, constitute the totality of patients presenting with dysglycaemia. Whereas the increased cardiovascular risk specifically related to diabetes in coronary patients is well known and documented, less attention has been given to prediabetes and its interaction with cardiovascular outcomes.

In the current issue of EuroIntervention, Kok et al present an analysis of clinical outcomes in a cohort of nearly 3,000 patients after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with implantation of biodegradable or non-degradable polymer drug-eluting stents (DES), according to their glycaemic status1.

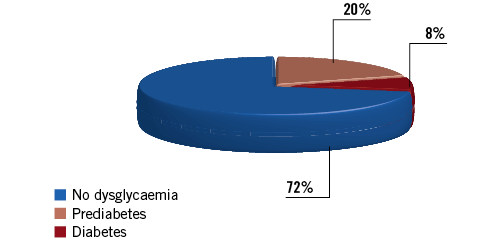

The first lesson is that 14% of the patients without previously known diabetes had prediabetes and an additional 7% had overt diabetes; overall, dysglycaemic patients represented 37% of the total population of patients undergoing PCI. These figures reflect the magnitude of the problem of unknown dysglycaemia in patients with coronary artery disease. They are in line with our own findings in the patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) included in the FAST-MI programme in France2: based on HbA1c levels at admission, 20% of the patients without previously recognised diabetes had prediabetes, and 8% had diabetes (Figure 1). In the Korean AMI registry, 59.5% of the patients without known diabetes undergoing primary PCI for STEMI had prediabetes3. Likewise, impaired glucose tolerance based upon an oral glucose tolerance test two weeks after discharge in a Spanish population undergoing PCI (76% for acute coronary syndromes) was found in 24.5%, with an additional 16% having newly diagnosed diabetes4.

Figure 1. Prevalence of dysglycaemia and newly diagnosed diabetes based upon HbA1c values in the FAST-MI 2005-2015 registries.

The second lesson is more encouraging: overall patient management was in line with current recommendations, and did not markedly differ according to diabetic status. In fact, patients with prediabetes received statins, newer P2Y12 inhibitors, beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers at least as often as non-dysglycaemic patients. The corollary is that one can hardly expect to improve the clinical outcomes of patients with prediabetes by improving prescription of cardiovascular medications at discharge.

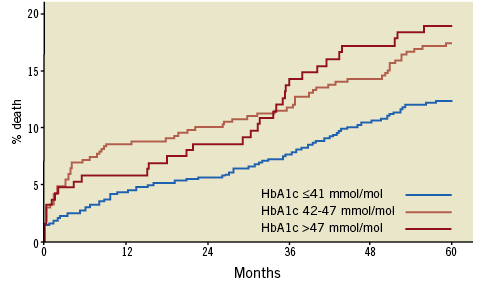

The third finding is that clinical outcomes were much poorer in dysglycaemic patients, including in terms of one-year mortality, and were similar between patients with prediabetes and those with diabetes. These findings should be interpreted in the light of the potential limitations of the study: in particular, the diagnosis of prediabetes was based either on HbA1c values or on fasting plasma glucose (FPG) values. If the former probably reflect the patients’ chronic glycaemic status, the latter can also reflect the extent of myocardial damage in patients presenting with AMI (>50% of the population), independently of their chronic glycaemic status. Judging by the low number of patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction, however, it seems unlikely that this confounding factor could have been more than a minor contributor to the worse outcomes observed in patients with dysglycaemia. In fact, in the French FAST-MI cohorts, and based only upon HbA1c values, the five-year mortality of prediabetic patients was close to that of diabetic patients (Figure 2). Recently, results from another contemporary cohort, in Korean patients treated with DES exclusively for stable coronary artery disease, showed increased two-year mortality (5.5% vs. 1.5%, p=0.007) in patients with prediabetes, as well as a trend to higher rates of in-stent restenosis (15.6% vs. 9.8%, p=0.066)5.

Figure 2. Five-year mortality in AMI patients without history of known diabetes, according to HbA1c levels at admission in the FAST-MI 2005 and 2010 registries.

Overall, if patients with prediabetes are indeed at increased long-term risk, with a risk similar to that of diabetic patients, what can we do to improve things? Optimisation of secondary prevention medications, as well as lifestyle modification is a prerequisite for improving outcomes. Newer hypoglycaemic medications (SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP1 agonists) reduce cardiovascular events in patients with recognised diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease6-8. Whether these medications can also improve outcomes in dysglycaemic patients without overt diabetes is unknown and will require specific clinical trials. So far, the effects of medications such as insulin glargine or n-3 fatty acids in patients with prediabetes have been disappointing9,10.

However, beyond these measures, the best revascularisation options in these patients should be carefully analysed, as they are in diabetic patients. A recent meta-analysis based on individual data of more than 11,000 patients randomised to coronary artery bypass surgery or PCI with stents for left main or multivessel disease has shown that there was no difference in outcome between the two revascularisation options in non-diabetic patients, whereas in diabetic patients mortality was considerably less with coronary artery bypass surgery, with a 5% difference in all-cause mortality at five years between the two revascularisation techniques11. These results, together with observational data in multivessel disease patients with either stable ischaemic heart disease or acute coronary syndromes (excluding STEMI patients ≤72 hours from admission)12, form the basis of the current European Society of Cardiology recommendation that coronary bypass surgery should be the preferred option in diabetic patients13. The present study, showing similar outcomes after stenting in patients with diabetes or prediabetes, therefore suggests that, at least in prediabetic patients with multivessel disease, coronary artery surgery might be the best revascularisation strategy when the operative risk is not considered too high. It might be time for interventional cardiologists and cardiac surgeons to envisage a contemporary comparative trial in the large population of patients presenting with prediabetes.

Conflict of interest statement

N. Danchin has received research grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Merck, Pfizer, and Sanofi and fees for lectures or consulting from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Servier.