Abstract

Aims: To analyse the ultrasound anatomy of bifurcation lesions {1,1,0},{0,1,0} and {1,0,0} of the Medina classification in order to identify predictors of angiographic side branch (SB) damage after main branch (MB) stenting.

Methods and results: One hundred and ten patients with Medina classification bifurcation lesions of {1,1,0},{0,1,0} and {1,0,0} were recruited. An intravascular ultrasound study (IVUS) was performed on the MB before treatment, after stent implantation and after SB intervention. A quantitative analysis was conducted in combination with a qualitative study of the carina morphology and plaque distribution. Ostial SB damage (an increase of the percentage of ostial stenosis by QCA ≥ 30%) was observed in 51 lesions (48%) after MB stenting. The baseline IVUS identified a carina with a spiky morphology (“eyebrow” sign) in 51 bifurcations. In 41 out of 51 bifurcations with this sign, ostial SB damage was induced after stenting the MB due to carina shift (p<0.01). Narrower angiographic angles were associated with the presence of the “eyebrow” sign (62º±23º vs. 76º±24º, p <0.05). Plaque located at the carina was associated with a lower rate of ostial SB damage (29%) when compared with those lesions with no plaque exhibiting at the carina (51%), p <0.05.

Conclusions: The “eyebrow” sign is a powerful predictor of ostial SB damage after stent implantation in the MB in bifurcation coronary lesions without plaque involving the SB.

Introduction

Coronary bifurcation lesions are frequent and may represent 15-20% of all percutaneous coronary interventions in daily practice1,2. Immediate success is lower, and the restenosis rate is higher, than in non-bifurcated coronary lesions3. However, there is a broad spectrum of presentations regarding plaque distribution and number of bifurcation components affected. Based on the Medina classification4, coronary bifurcation lesions that do not involve the SB origin include type {1,0,0}, {1,1,0} and {0,1,0} lesions. Approaching these lesions with provisional stenting has shown to be effective5-7, and the procedure may be completed after stenting the main vessel. Nevertheless, during the treatment of these lesions, the SB ostium may be damaged (defined as increasing the percentage of stenosis by QCA), and in some cases, the SB may be totally occluded. Different mechanisms have been suggested to explain this ostial damage8-12, such as plaque shift, refractory spasm or dissection of the ostium. Baseline angiography is unable to fully predict this damage, and only an acute bifurcation angle12 has been associated with induction of ostial SB damage after stent implantation in the MB. On the other hand, there is little information about the ultrasound anatomy of such lesions or the stent’s possible impact as it alters the complex anatomy of the bifurcation.

The purpose of this study was to analyse ultrasound anatomy at the baseline and after stenting the MB in a group of Medina coronary bifurcation lesions in order to identify possible predictors of ostial SB damage and the related mechanisms.

Methods

Patients

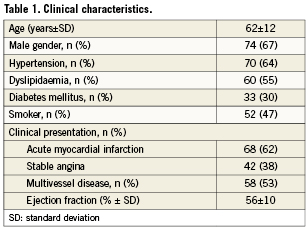

We studied 99 patients with 110 bifurcation coronary lesions that did not involve the SB ostium (Medina classification {1,0,0}, {1,1,0} and {0,1,0}). Lesions in which SB reference diameter was ≤ 2.25 mm were excluded. Written consent was obtained from all patients. The patients’ clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Most patients were males with hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and multivessel disease. All underwent diagnostic cardiac catheterisation. After the diagnosis, and having documented by angiography the presence of a coronary bifurcation lesion not involving the SB origin, an IVUS was performed at baseline and after stenting the MB.

Diagnostic and therapeutic procedure

Diagnostic cardiac catheterisation, including left ventriculography and sequential coronary angiography, was performed in all patients. Two orthogonal views, showing the SB ostium as clearly as possible, were obtained in all cases. A 1 mg/kg dose of sodium heparin was administered upon completion of the diagnostic phase. The baseline ultrasound study was performed after wiring both vessels of the bifurcation. A drug-eluting stent was then selected according to the reference diameter. The two orthogonal angiographies selected in the diagnostic phase were repeated after stent implantation in order to evaluate the SB ostium. A new IVUS of the MB was then conducted. SB damage was defined as an increase of the percentage of ostial stenosis by QCA ≥ 30%, as compared with the basal condition. A balloon angioplasty was performed when the stenosis of the SB ostium was ≥50%. The IVUS of the MB was then repeated. At the end of the procedure, heparin was neutralised with protamine and the femoral puncture site was sealed with Angio-Seal® (St. Jude medical, St. Paul, MN, USA). The MEDIS system (CMS 7.1; MEDIS, Leiden, The Netherlands) was used for all angiographic measurements, performed offline by two experienced interventional cardiologists.

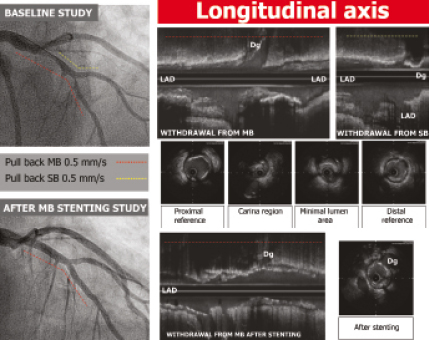

Intravascular ultrasound study

The IVUS protocol is illustrated in Figure 1. After administration of an intracoronary bolus of nitroglycerine, a motorised pullback (0.5 mm/sec) was performed from the MB distal reference (Atlantis SR; [Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA] 2.5 Fr, 40 MHz, or Avanar F/X; [Volcano Therapeutics Inc., Rancho Cordova, CA, USA] 2.9 Fr, 20 MHz). In 49 lesions (44%), a pullback from the SB was also performed at baseline condition. The area of the external elastic membrane, the luminal area and the plaque burden were determined at different levels: the proximal reference, the point of minimal lumen area, the carina region and the distal reference. The qualitative study of the bifurcation was done based on the longitudinal IVUS reconstruction, selecting the best view in which the carina and the SB origin could be clearly defined. To obtain the best view of the carina, it is useful during the pull back to visualise the SB wire in the cross section and then to point the axis towards the wire. This view seems to be similar to that employed by pathologists in diseased coronary bifurcations and enables analysis of plaque distribution and carina morphology. Plaque at the carina was defined as the presence of atheroma with a thickness ≥ 0.3 mm. The IVUS study was repeated after stenting the MB, in order to assess the stent’s impact on the anatomy of the bifurcation lesion. A third IVUS study was performed in all patients who required SB angioplasty.

Figure 1. Ultrasound study protocol.

Statistical study

The quantitative variables are expressed as mean ±standard deviation. The qualitative data are expressed as percentages. To compare mean values, we used Student’s t-test. The chi-squared test was used to compare qualitative variables. Statistical significance was defined as p <0.05. Statistics were calculated with the SPSS computer program, release 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Angiographic findings

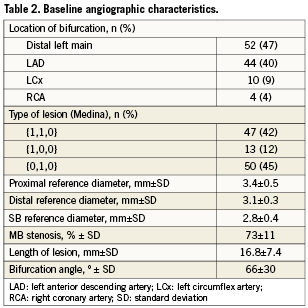

Table 2 shows the baseline angiographic data. The most common bifurcation observed was the distal left main (47%) and the left anterior descending artery (LAD) with the diagonal branch (42%). Lesions {0,1,0} of the Medina classification were predominant (45%).

In 51 lesions (46%), ostial SB narrowing was observed after stent implantation in the MB, resulting in significant stenosis (≥50%) in 31 lesions (28%), while in the remaining 20 cases, the stenosis was mild (≤50%). In 26 cases, the SB was treated with angioplasty, 15 with a single balloon and 11 with simultaneous kissing balloon, obtaining a good angiographic result in 25. One patient required a second stent at the SB due to poor TIMI flow after undergoing SB angioplasty.

Ultrasound findings

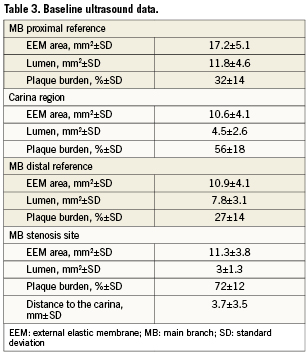

Table 3 displays the quantitative IVUS results. The plaque burden at the minimal lumen area (MLA) in the MB was 71%. The MLA was located only at the carina region in 33 lesions (30%). While the MLA was observed to be both proximal and distal to the carina region, it was close to the carina on average (with a mean distance of 3.7±3.5 mm). The baseline IVUS of the SB showed a plaque burden at the ostium of 11±9%, and in 30 out of 49 bifurcations, no plaque at all was observed at the SB ostium.

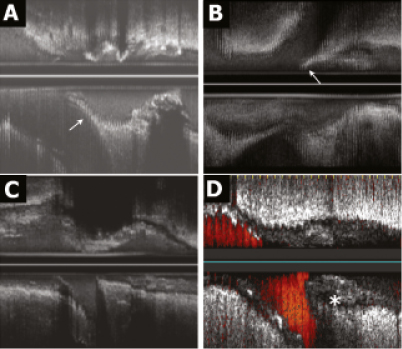

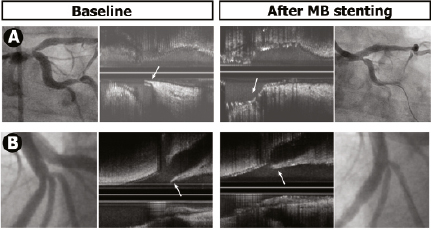

Qualitative analysis of the longitudinal IVUS reconstruction identified a singular anatomic pattern of the carina in 51 bifurcations (46%), characterised by the spiky morphology known as the “eyebrow” sign13 (Figure 2A, 2B). This sign represents an initial parallel course of the SB origin and the MB, sharing the flow divider until the SB undergoes a change of direction. This lack of angulation is not detected by the angiography and is only detectable by IVUS. Based on the location of the bifurcation, the prevalence of this feature changed: in LAD with the diagonal (Dg), the eyebrow sign was observed in 25 out of 44 cases (56%), in the left circumflex with the marginal branch in five out of 10 cases (50%), in the distal left main, in 21 out of 56 cases (40%) and, in the right coronary artery, in one out of four cases (25%).

Figure 2. Carina morphology and plaque distribution. The different morphologies of the carina identified in the longitudinal axis of the IVUS are shown in this figure. A and B (arrows) present a spiky carina (“eyebrow” sign) in the longitudinal reconstruction. This feature is absent in C and D. Notice that in A, B and C, the carina is free of plaque, while in D there is plaque at the carina (asterisk).

Regarding plaque distribution at the carina region, most of the lesions exhibited a distribution pattern with no plaque at the carina and plaque at the counter-carina. However, in 27 lesions (25%), plaque was observed located at the carina. In these lesions the plaque thickness at this level was 0.8±0.2 mm, and at the contra-lateral wall (counter-carina) the plaque thickness was 1.2±0.5 mm (p<0.05). Only in four of these bifurcations the amount of plaque was greater in the carina (Figure 2D).

Study of SB damage predictors

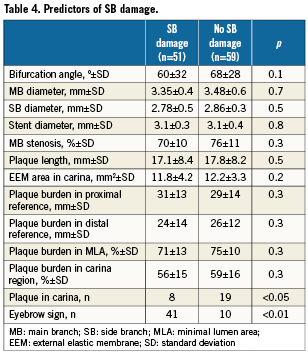

The angiographic and ultrasound variables that could be potential predictors of ostial SB damage after stent implantation in the MB were analysed (Table 4). There were no significant angiographic differences between patients with and without ostial SB damage. The “eyebrow” sign detected in the baseline longitudinal ultrasound examination was a predictor of ostial SB damage. In 41 out of 51 lesions presenting this feature (80%), ostial SB stenosis was documented after stenting the MB (p< 0.01). Sensitivity and specificity were 0.8 and 0.83, respectively. The positive predictive value was 0.8 and the negative predictive value was 0.83. The relative risk of damage to the SB ostium in the presence of this sign was 4.74 (96% confidence interval [CI]: 1.47-15.27).

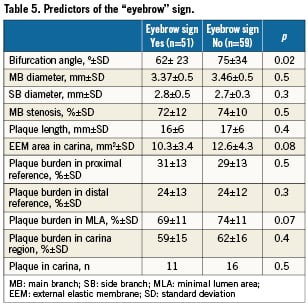

The predictors of the eyebrow sign were also studied (Table 5). Only a narrower angle was associated with the presence of this sign (62º±23º vs. 76º±24º, p=0.023). However, although there was a trend, the acute angle was not an angiographic predictor of ostial SB damage. The IVUS after stent implantation showed that pinching of the SB was induced by carina shift leading to an ostium jailing and to an angiographic stenosis (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Two examples illustrating the SB damage mechanism in bifurcations with the “eyebrow” sign. Baseline angiography and the IVUS are presented on the left and post-stenting on the right. Note how the stent’s displacement of this type of carina (arrow) induces ostial stenosis in the SB.

On the other hand, only eight patients out of 27 (29%) with plaque involvement of the carina suffered SB damage after stenting the MB, while this happened in 43 out of 83 bifurcations (51%) with no plaque at the carina (p<0.05). The snowplough phenomenon was rare, and it was observed in only one case, shifting the plaque from the proximal MB towards the SB ostium.

Discussion

Bifurcation coronary lesions without involvement of the SB origin can represent up to 50% of bifurcation lesions treated percutaneously in daily practice. The procedure is usually completed once the stent is deployed in the MB, if there is no ostial SB damage. However, after treating the MB, ostial SB narrowing may occur, requiring subsequent treatment. Different mechanisms have been suggested to explain this damage, such as the snowplough phenomenon, spasm or dissection of the SB ostium. The possibility of predicting such damage with angiography is limited, and there is little information available concerning the ultrasound anatomy of these lesions.

In this study, we used IVUS to analyse a series of patients with disease-free SB coronary bifurcation lesions, before and after treatment, in order to identify possible predictors of ostial SB damage and to analyse the mechanisms of such damage.

A recent study13 identified a morphological pattern of the carina detected by IVUS, the “eyebrow” sign, and this was proposed as a predictor of ostial SB damage in ostial LAD lesions. This sign consists of the presence of a spiky carina, with variable length and orientation. It can be identified by longitudinal IVUS reconstruction, achieved by rotating the axis (180º scan), as this feature only appears occasionally in one sector of the circumference.

In our study, the prevalence of the “eyebrow” sign was greater in LAD-Dg bifurcation lesions (56%), and was associated with smaller angles. However in distal left main bifurcation lesions, despite wider angles, the “eyebrow” sign was also observed in 21 out of 56 lesions (Figure 2A and 3A).

This study confirms that this sign is a powerful predictor of damage throughout the bifurcation spectrum ({1,1,0},{0,1,0} and {1,0,0}), irrespective of the lesion’s anatomical location, and exhibiting high sensitivity, specificity and predictive value. Focal ostial SB narrowing was documented in 41 lesions out of 51 (80%) with this carina morphology, whereas the incidence of ostial damage without the “eyebrow” sign was only 16% (p <0.01). IVUS study after stent implantation enabled us to analyse the mechanism of this damage: stent displacement of this type of carina, which induces pinching and jailing of the SB ostium (Figure 3). However, this damage was variable, and the SB did not always need to be treated. In view of our findings, we believe that if a baseline IVUS study is performed on these lesions and this vulnerable carina anatomy is identified, it would be reasonable to select the stent diameter according to the distal reference, optimising the proximal stent with a larger balloon diameter -POT technique14 only when access to the SB has been ensured by passing a wire through the cell. This may reduce the degree of carina displacement and, therefore, the damage induced in the SB. On the other hand, when this sign is absent, a non-bifurcated lesion strategy could be adopted, without the need to protect the SB with a guidewire, as the possibility of damage is low.

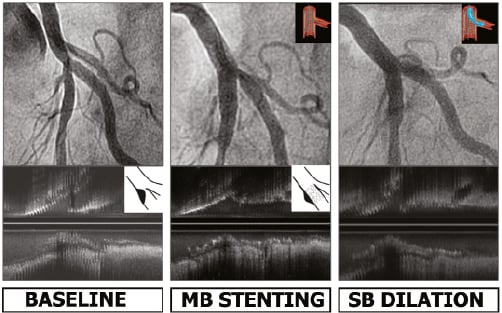

The ostial stenosis was significant (≥ 50%) in 31 cases, and intervention was applied at operator discretion in 26 cases. A good angiographic outcome was obtained in 25 of the 26 angioplasties, and subsequent IVUS study of the MB revealed endoluminal repositioning of the displaced carina and an opening in the stent cell consistent with the angiographic outcome (Figure 4). Angioplasty was performed with a single balloon in 15 cases and with kissing balloon inflation in 11 cases. The differences in stent geometry found using these two techniques were similar to those reported in prior studies15,16, although it is yet to be seen whether these differences have clinical implications for long-term follow-up. In the treated patients, we obtained excellent results; a second stent was required in only one patient. However, systematic intervention on the SB ostium is controversial, as highlighted by the findings reported by Koo et al17,18, showing fractional flow reserve values above 0.75 in severe angiographic stenosis (>50%). We believe that use of the pressure wire to evaluate the jailed branch makes the procedure more complex (the technique is costly and time consuming, and wiring of the jailed SB may induce ostial dissection, as it is not a dedicated wire). The angiographic and ultrasound outcomes obtained in our study lead us to believe that the intervention is justified when guided by ultrasound.

Figure 4. Angiography and IVUS at baseline, after MB stenting and after SB angioplasty. Carina shift induces ostial stenosis in the SB. Angioplasty provides endoluminal displacement of the carina, correcting the angiographic stenosis.

Regarding plaque distribution, the longitudinal view of the IVUS is an excellent tool for analysis. In our study, plaque was documented at the carina in 27 bifurcations (25%) (Figure 2D). This finding contradicts the statement that the carina is spared of plaque due to the atheroprotective mechanism provided by the high wall shear stress19 at this level of the bifurcation. Van der Giessen et al20 found a similar prevalence of plaque at the carina when using angio-CT scan to analyse plaque distribution. They observed plaque at the carina in 30% of the cases; this finding was predominantly observed when plaque was imaged in the contralateral wall with plaque growing from these low shear stress areas to the high stress carina areas. We obtained similar results at the contralateral wall with a plaque thickness of 1.2 mm vs. 0.8 mm at the carina. However, in our study, in four bifurcations (16%), we observed a larger amount of plaque at the carina (Figure 2D). Recently Medina et al21 also reported a prevalence of plaque at the carina of 32% in 195 coronary lesions analysed by IVUS. However, Oviedo et al22 concluded in an IVUS study of 140 distal left main lesions that the carina is always free of plaque. This discrepancy could be explained by the different approaches to patient selection and methodologies used in both studies. Oviedo et al selected patients with a lower severity of disease and used cross-sections to analyse plaque distribution, while we analysed the longitudinal axis as well, which clearly determines the presence or absence of plaque at the carina. When we analysed the impact of plaque distribution on the development of ostial side branch damage, we observed that bifurcations with plaque at the carina had a lower rate of ostial stenosis after MB stenting (eight out of 27, 29%) when compared with those bifurcations with the carina free of plaque (43 out of 83, 51%, p <0.05). Although plaque shift in bifurcations with plaque at the carina could be seen as an ideal scenario, it was not observed in any of the eight cases with plaque at the carina and ostial SB damage. The presence of plaque at this level may minimise carina displacement after MB stenting and, therefore, reduce the possibility of damage to the SB. Nevertheless, further information is required to confirm this hypothesis. Plaque shift was documented in only one patient in our study, moving from the proximal MB towards the SB. However, plaque located at the distal MB or at the carina never shifted. Similar findings were observed by Koo et al23, who recently reported that plaque shift always occurs from the proximal MB.

In relation to the angiographic variables analysed, the carina angle was smaller in the group of patients with SB damage (60º vs. 69º), although this difference was not significant (p=0.18). Previous studies suggest that smaller angles are associated with SB damage or occlusion. Vassilev et al12 reported that the alpha angle (an angiographic measurement of SB angulation) was a powerful predictor of SB damage after stent implantation in the MB. However, angiographic angle measurement may have important limitations. Angle breadth varies with projection, and extreme projections are occasionally required to correctly define the initial trajectory of the SB. Indeed, Vassilev´s study excluded 30% of the bifurcations because they were unable to correctly define the angle.

Limitations

In our study we did not perform IVUS of the jailed SB to avoid possible complications, overlooking important information. Sometimes the IVUS presents technical limitations, as poor IVUS catheter alignment with the vessel’s axis, can lead to errors in measuring and interpreting cross-sections, because it is not perpendicular. In wide angulations, the IVUS catheter may jump during the pull-back, and cause difficulties in correct interpretations and reconstructions of the longitudinal view.

Regarding angle measurements, angiography exhibits limitations due to overlap, being sometimes incapable of defining the angle, despite extreme projections. In this respect, rotational angiography and three-dimensional reconstruction software could be promising possibilities.

Finally we do not believe that the routine utilisation of IVUS should be mandatory in this type of lesion. In this series, we describe a singular anatomical feature that explains the main mechanism of ostial SB damage and its simple correction.

Conclusions

Using longitudinal reconstruction, baseline IVUS identified an anatomical feature of the carina (“eyebrow” sign) in coronary bifurcation lesions without involvement of the SB. This sign is a predictor of ostial SB stenosis after MB stenting. Displacement of this type of carina appears to be the principal mechanism of damage in this type of lesion, and its repositioning with angioplasty appears to ensure a positive outcome. In almost one-third of the lesions (25%), plaque was documented at the carina. This plaque distribution pattern was associated with a lower incidence of ostial SB damage.

Conflict of interest statement

All authors have no conflict of interest to declare.