Abstract

Aims: To assess the procedural and long-term results of non-compliant (NC) kissing balloon inflation (KB) in patients undergoing bifurcation intervention with the provisional side branch (SB) stenting technique. Provisional SB stenting is the default strategy for coronary bifurcation intervention. Recent data have suggested that KB with compliant balloons increases the risk of SB dissection and restenosis. However, NC KB may reduce SB complications.

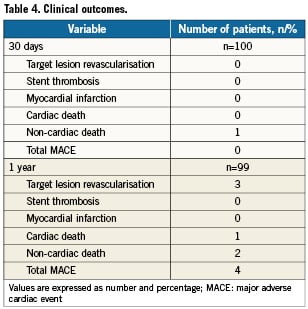

Methods and results: We prospectively enrolled patients undergoing provisional SB stenting at two French centres. KB was systematically performed with NC balloons. Quantitative coronary angiography and digital stent enhancement (DSE) were performed in all cases. Thirty-day and one-year major adverse cardiac event (MACE) rates were assessed. We recruited 100 patients with a mean age of 67.3±11.7 years. Diabetes mellitus was prevalent in 23%, renal dysfunction in 21%, and multivessel disease in 69%. Intervention was performed for stable angina in 48% and acute coronary syndromes in 27%. Target lesions were the left main in 15% and the left anterior descending in 51%. True bifurcation stenoses accounted for 46% of lesions (Medina class: 1,1,1/1,0,1/0,1,1). All lesions were successfully treated with NC KB. SB stenting was required in 6% (five dissections, one residual stenosis). Using DSE, a SB stent scaffold was evident in 89% following KB. The cumulative 12-month MACE rate was 4%. Target lesion revascularisation was required in 3%. No stent thrombosis occurred during follow-up.

Conclusions: Provisional SB stenting followed by NC KB is associated with high procedural success and low rates of clinical target lesion failure.

Abbreviations

atm: atmospheres

CK: creatinine kinase

KB: kissing balloon

MACE: major adverse cardiac event

MI: myocardial infarction

MLD: minimal luminal diameter

MV: main vessel

NC: non-compliant

PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

POT: proximal optimisation technique

QCA: quantitative coronary angiography

SB: side branch

TLR: target lesion revascularisation

Introduction

The treatment of coronary artery bifurcation stenoses represents a technical challenge for the interventional cardiologist. Treatment of this complex lesion subset continues to demonstrate lower rates of procedural success and increased rates of clinical restenosis compared to non-bifurcation percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI1).

The default percutaneous strategy for bifurcation PCI is a provisional approach of implanting a single stent in the main vessel (MV) with additional stenting of the side branch (SB) only in the presence of residual significant SB lesions. Simultaneous kissing balloon (KB) post-dilatation is recognised as an integral step in complex bifurcation PCI2,3, although its systematic use in provisional SB stenting remains controversial4. Final KB inflation in single-stent bifurcation PCI has several theoretical advantages, however it has been suggested that the use of compliant balloons for kissing post-dilatation may result in underexpansion of the MV stent, and significant overexpansion of the SB ostium (Dr Yoshihisa Kinoshita, European Bifurcation Club, 2010), thus increasing the risk of SB injury5,6 and adverse clinical outcome (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Bench testing of kissing post-dilatation with compliant and non-compliant balloons. Images from bench tests of kissing balloon post-dilatation with: (A) semi-compliant (Ryujin); and (B) non-compliant (Hiryu) balloons in a Cypher Select stent. Semi-compliant balloons cause over-expansion (“melon-seeding”) of the side branch ostium. Image courtesy of Dr Yoshihisa Kinoshita, Division of Cardiology, Toyohashi Heart Centre, Toyohashi, Japan

The objective of this study was to evaluate the feasibility, safety and long-term clinical outcomes of systematic simultaneous KB angioplasty with NC balloons in patients undergoing bifurcation PCI with the provisional SB stenting technique.

Methods

Study population

This prospective observational study recruited consecutive patients undergoing bifurcation PCI with a provisional single stent strategy, in catheterisation laboratories equipped with the StentBoost digital stent enhancement system (Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands), at two French centres between January and December 2009. All patients ≥18 years of age, with stable or unstable coronary syndromes, and de novo coronary artery bifurcation stenoses were considered eligible for study inclusion. Bifurcation lesions were defined as a stenosis ≥50% in the MV with or without stenosis of the ostium of the SB. The required reference diameters for the MV and SB were ≥2.5 mm and ≥2.00 mm, respectively. Interventions for acute myocardial infarction (MI) and left main coronary artery lesions were eligible for enrolment. Exclusion criteria included a planned two-stent PCI strategy, cardiogenic shock, chronic total occlusion, and contraindications to dual antiplatelet therapy. Patient demographic data, lesion location and morphology, and procedural data were recorded. All patients provided written informed consent.

Procedures

The provisional SB stenting technique with final KB angioplasty was the default strategy for all patients, and has been described in detail elsewhere7,8. Briefly, after placing angioplasty guidewires in both branches, the MV is dilated or directly stented across the SB, with a stent sized appropriately for the reference diameter of the MV distal to the origin of the SB. Predilatation of the SB is not recommended as it may increase the rate of SB dissection. If a significant size difference between the proximal and distal MB exists, as is the case with large SB9, or access to the SB is difficult, then a proximal optimisation technique (POT)10 is performed with a short NC balloon. The guidewires in the MV and SB are carefully exchanged (MV first), ensuring a distal stent strut passage for the SB guidewire. Simultaneous KB angioplasty is subsequently performed with NC balloons appropriately sized for each vessel. We used the NC Hiryu® balloon (Terumo Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) for all cases in this study due to their low entry profile (0.42 mm) and high-pressure resistance (rated burst pressure: 20 atmospheres [atm]/2,026 kilopascals). Stenting of the SB was performed only in the presence of a significant dissection (>grade B) or residual SB stenosis (visual estimation >70%). A final simultaneous KB post-dilatation was performed if SB stenting was required (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Provisional SB stenting and kissing balloon post-dilatation with compliant (A) and non-compliant (B) balloons. Compliant balloon kissing inflation causes “melon-seeding” (A3) and dissection (A4) at the ostium of the side branch (SB), necessitating a second stent. Over-dilatation of the SB ostium does not occur with non-compliant kissing balloon inflation

All patients were pretreated with aspirin and clopidogrel before the index procedure. A 600 mg loading-dose of clopidogrel was administered at least three hours prior to PCI if patients were not taking daily thienopyridine therapy. During the procedure, patients received intravenous unfractionated heparin to maintain an activated clotting time of ≥300 seconds. The use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors was at the operator’s discretion. Electrocardiograms were recorded and total creatinine kinase (CK) was measured prior to PCI, and routinely 12-24 hours after the procedure. After discharge, aspirin was continued indefinitely, and clopidogrel was continued for at least six months.

Quantitative coronary angiography

Coronary angiography was performed after intracoronary injection of isosorbide dinitrate (1 mg) and orthogonal views were used for quantitative coronary analysis (QCA). All bifurcation lesions were classified according to the Medina classification11 following QCA in the angiographic view which best displayed the entire bifurcation with minimal foreshortening. Angiograms were analysed offline with a dedicated bifurcation system (CAAS version 8.2; Pie Medical Imaging, Maastricht, The Netherlands12,13). This system performs simultaneous QCA analysis on the MB and SB in a single acquisition. The proximal MV, distal MV and SB reference vessel diameter, minimal lumen diameter (MLD), and percent diameter stenosis were measured pre- and post-stent implantation. The bifurcation angle, defined as the angle between the axis of the distal MV and the axis of the SB at its origin, was measured in the angiographic view in which the QCA measurements were performed. Angiographic success was defined as a residual MV stenosis <20%, in the absence of significant SB compromise.

Digital stent enhancement

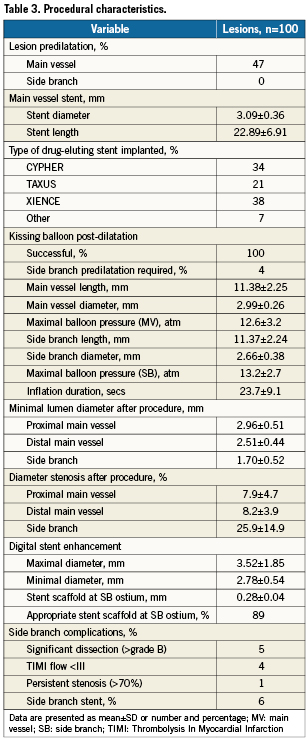

Digitally enhanced stent images were acquired in all cases with StentBoost (Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands), a validated commercially available software package. The technique of digital stent enhancement used by StentBoost has been previously described elsewhere14,15. For each lesion, the flat-panel detector was positioned to minimise stent foreshortening and the angiographic field was narrowed to include only the guiding catheter and the stented segment. With the stent balloon markers within the stented segment, 45 frames of digital cine were acquired at 30 frames per second, without contrast injection. The outer border of the stent was traced manually and, using the guide catheter as a reference, the minimum and maximum stent diameters were automatically calculated by the digital enhancement software. The presence of an acceptable “stent scaffold” was defined as the protrusion of visible stent strut ≥0.25 mm into the ostium of the SB (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Digital stent enhancement. Digital stent enhancement following main vessel stenting (A); proximal optimisation technique (B); and kissing balloon inflation (C) demonstrates gradual tapering of the stent and a “stent scaffold”

Clinical definitions and follow-up

Creatinine clearance was calculated with the Cockcroft-Gault formula, and renal dysfunction was defined as a glomerular filtration rate <90 mL/min–1/1.73 m–2. Procedural success was defined as angiographic success without the occurrence of death, MI, or repeat revascularisation of the target lesion during the hospital stay. Clinical follow-up was performed by hospital visit or patient telephone interview at one and 12 months. We evaluated the rate of major adverse cardiac events (MACE), defined as the composite of cardiac death, Q-wave or non–Q-wave MI, or target-lesion revascularisation (TLR) at one and 12 months. Periprocedural MI was defined as either an increase in CK-MB (or CK) ≥3 times the upper limit of normal (ULN) and at least 50% over the most recent pre-PCI levels, or the development of new ECG changes consistent with MI and CK-MB (or CK) elevation higher than the ULN at two measurements for patients undergoing PCI in the setting of stable angina or non-Q wave MI and falling or normal CK-MB (or CK) levels. Recurrent chest pain lasting >30 min with either new ECG changes consistent with second MI or next CK-MB (or CK) level at least 8-12 hours after PCI elevated at least 50% above the previous level was considered procedure-related MI for patients presenting with non-Q-wave MI and elevated CK-MB (or CK) level prior to PCI. Spontaneous MI was defined as any CK-MB (or CK) increase with or without the development of Q-waves on ECG. TLR was defined as either surgical or percutaneous revascularisation driven by significant (>50%) luminal diameter narrowing either within the stent or the 5 mm borders proximal and distal to the stent. Stent thrombosis was assessed based on the definitions of the Academic Research Consortium16.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages and were compared with the chi-square test. Continuous variables were analysed for a normal distribution with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (using p-value >0.2 as a threshold). Normally distributed variables are presented as mean±standard deviation. Variables that did not follow a normal distribution are represented as median and interquartile range. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS (version 17; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

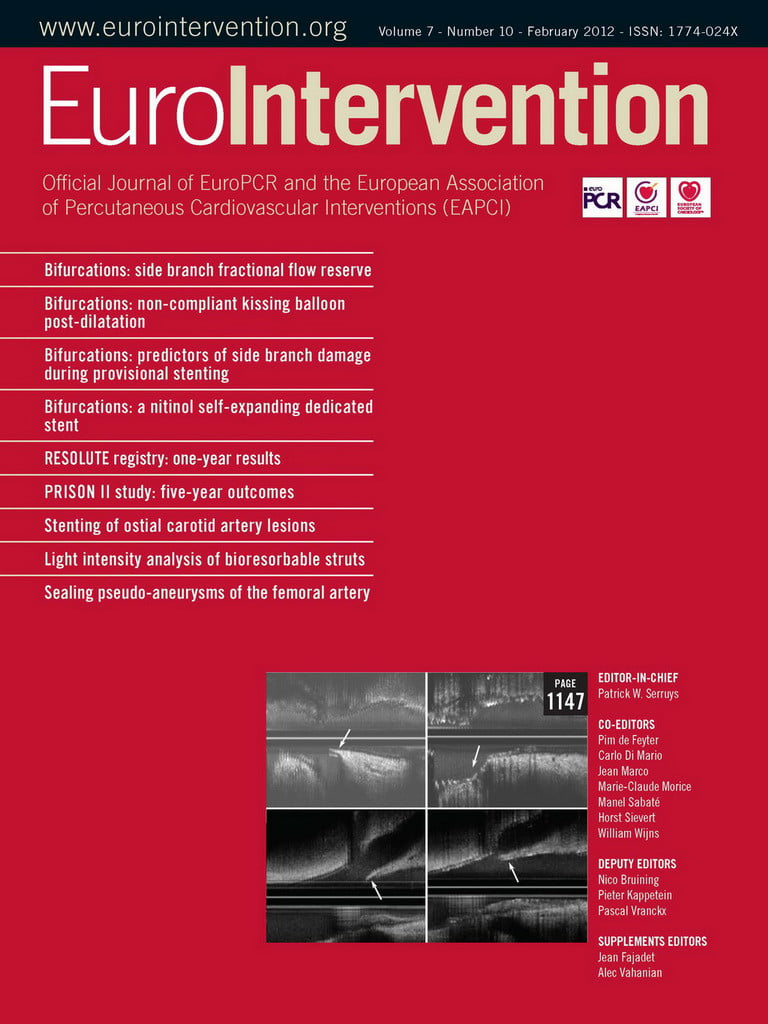

Among 106 consecutive patients with bifurcation lesions presenting for percutaneous revascularisation, 100 patients underwent provisional SB stenting and were suitable for study inclusion. Patient demographics and clinical characteristics are outlined in Table 1. The mean age of the cohort was 67.3±11.7 years, and 77% were male. Diabetes mellitus was prevalent in 23%, renal dysfunction in 21%, and multivessel disease in 69% of cases. The indication for PCI was stable angina in 48%, silent ischaemia in 22%, unstable angina pectoris/non-ST-elevation MI in 25% and ST-elevation MI in 5%.

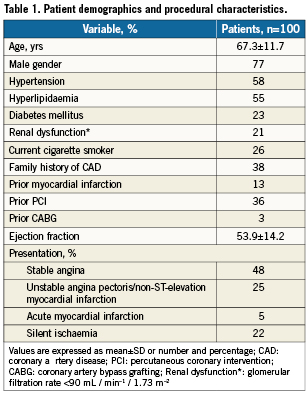

Baseline angiographic characteristics are listed in Table 2. The target of the bifurcation intervention was the distal left main stem coronary artery in 15%, the left anterior descending/diagonal branch in 51%, the circumflex/obtuse marginal in 22% and the distal right coronary artery in 14%. According to the Medina classification, 46% of our cohort had true bifurcation lesion morphology ([1,1,1], [1,0,1], [0,1,1]).

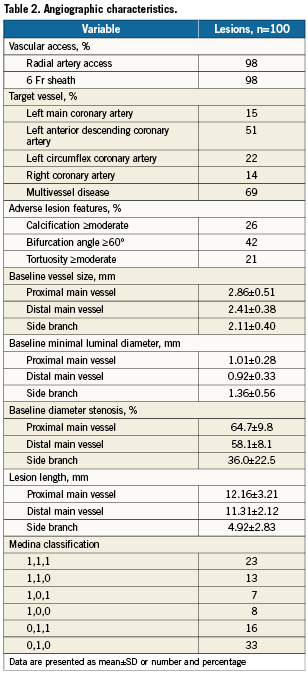

Pre-dilation of the MV was performed in 47% prior to stent implantation (Table 3). The SB was not pre-dilated prior to MV stenting in any case. The stents most commonly used were the XIENCE V everolimus-eluting stent (Abbott Vascular, Redwood City, CA, USA) (38%), the CYPHER Select sirolimus-eluting stent (Cordis, Johnson & Johnson, Warren, NJ, USA) (34%), and the TAXUS® Liberté paclitaxel-eluting stent (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) (21%). In 96% of cases, KB post-dilatation was possible without pre-dilatation of the SB. Final KB was performed in all cases. The maximal balloon inflation pressure was 12.6±3.2 atm in the MV and 13.2±2.7 atm in the SB, for a mean duration of 23.7±9.1 seconds. Digital stent enhancement illustrated an acceptable “stent scaffold” at the ostium of the SB in 89% after final KB angioplasty. There was a lower rate of SB stenting (3.4% [3/89] versus 27.2% [3/11], p=0.032) and a trend towards a reduction in SB complications at the SB ostium in patients with a stent scaffold compared to those without (7.9% [7/89] versus 27.3% [3/11], p=0.078). Side branch stenting was required in 6% of patients, due to significant SB dissection in 83.3% of cases, and persistent significant stenosis in 16.7% of cases. Three of five significant SB dissections were caused by the KB post-dilatation. Angiographic success was achieved in all patients.

Clinical outcomes

Clinical follow-up data at 12 months was available in 99 patients and demonstrated a cumulative MACE rate of 4%. The individual adverse events at 30 days and 12 months are shown in Table 4. There were three deaths during follow-up: one patient suffered an embolic stroke on day four, one patient died from septic shock after three months, and the last patient developed cardiogenic shock and multi-organ failure following admission with critical lower limb ischaemia, six months after PCI. Of the forty patients (40%) who underwent non-invasive testing for myocardial ischaemia during follow-up, at a mean duration of 15±2.6 months, three patients (3%) had evidence of ischaemia and subsequently required TLR. Two of the three patients who required TLR had bifurcation PCI for distal left main coronary stenosis. Both of these patients required SB stenting during the index procedure, one for persistent stenosis and the other for a significant dissection. One patient underwent repeat left main PCI and the other required coronary artery bypass grafting. The other case of TLR was treated by repeat PCI. No predictors of TLR were identified with multivariate analysis. There were no cases of stent thrombosis or MI during the 12-month follow-up period.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that provisional SB stenting with NC KB post-dilatation in coronary bifurcation lesions is feasible and safe. This strategy resulted in a low (6%) rate of SB stenting during the index procedure and a promising 12-month MACE rate of 4%.

Randomised trials have demonstrated that the systematic use of complex stenting techniques in the treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions does not improve patient outcome17-27. Rather, they increase procedural complexity, radiation exposure, contrast use, cost and the rate of periprocedural MI22. Thus, provisional SB stenting is considered to be the default strategy for bifurcation PCI. However, there is a lack of consensus on technical aspects of the provisional SB stenting technique4. In particular, experts are divided on the necessity for KB inflation after MV stenting. Kissing balloon post-dilatation has several potential advantages. Firstly, as there is a step down in the reference diameter of the MV from proximal to distal, as described by Finet’s adaption of Murray’s law28, the MV stent should be sized for the distal MV reference diameter in order to avoid distal stent edge dissection. Subsequent KB inflation optimally deploys the relatively undersized stent in the proximal MV, albeit resulting in a conical shaped stent. Furthermore, if the guidewire exchange is performed via a distal stent strut the final KB dilatation creates a “stent scaffold” at the ostium of the SB, which reduces the risk of acute SB dissection and potentially reduces ostial SB restenosis (Figure 3). Finally, KB post-dilatation allows successful treatment of physiologically significant SB stenosis30, without displacing the MV stent on the side opposite the bifurcation, as is the case with SB balloon dilatation alone29.

Despite these potential advantages, KB post-dilatation is not systematically performed after single-stent bifurcation PCI. In the randomised NORDIC and British Bifurcation Coronary Study (BBC One) trials, KB post-dilatation was performed in 31% and 32% of patients treated with a single stent19,22. In the The Nordic-Baltic Bifurcation Study III, the first randomised comparison of systematic KB post-dilatation with no kissing inflation in patients undergoing provisional SB stenting31, a final KB inflation significantly reduced angiographic SB restenosis (7.9% versus 15.4%, p=0.039), especially in true bifurcation lesions (7.6% versus 20.0%, p=0.024), albeit without impacting on clinical outcomes.

Thus, it is possible that further technical refinement of KB post-dilatation could impact on clinical outcomes. The use of NC balloons for kissing post-dilatation may represent one such improvement as compliant and semi-compliant balloons increase in length during deployment and “melon-seed” during kissing inflation (Figure 1)6. Thus, a technique designed to optimise the angiographic result of the SB can potentially cause endothelial disruption or frank dissection at the SB ostium, or indeed provide a nidus for SB restenosis (Figure 2). In contrast, NC balloons maintain their specific dimensions during high-pressure or KB inflation and are less likely to damage the SB ostium. Following NC KB post-dilatation, only 6% of patients in our study required a SB stent, which compares favourably to other studies of provisional SB stenting with systematic KB post-dilatation where NC balloons were not used per protocol20,21.

In addition to favourable procedural results, the strategy of NC KB post-dilatation resulted in a low rate of MACE (4%) and TLR (3%) at 12-month follow-up. Indeed, of the three cases requiring TLR at 12 months, two patients had SB stenting during the index procedure. Previous studies of provisional SB-stenting with systematic KB post-dilatation have reported cumulative MACE rates of 15% (11% TLR) and 13% (11% TLR) at six and 12 months, respectively20,21. Importantly, repeat angiography was performed per protocol in both of these studies and may have influenced the re-intervention rates. Nevertheless, the low rate of repeat revascularisation in our cohort at 12 months is comparable to that of non-bifurcation lesions and is, we believe, derived from the techniques employed during the initial PCI. In addition to NC KB post-dilatation, liberal use of the POT technique and KB inflation following a distal stent strut wire passage during guidewire exchange resulted in a “stent scaffold” at the SB ostium in 89% of our cohort. It is possible that this DES scaffold reduces the rate of acute SB complications, and may also play a role in reducing the rate of clinical SB restenosis.

Study limitations

This study was designed as a mechanistic cohort study to assess the feasibility and safety of systematic KB post-dilatation with NC balloons, and therefore, we did not randomise patients to a strategy of compliant or NC KB inflation. However, previous studies have described SB dissection rates of between 5-12% when systematic compliant balloon inflation was performed20,21. We did not perform systematic angiographic follow-up in our patient cohort and while routine 6- or 12-month angiography may have given additional information, it could have resulted in overestimation of the clinical benefit of particular treatment strategies16,31,32. The relatively small numbers of patients included in the trial limit the development of definitive conclusions.

Conclusions

The results of this prospective pilot study demonstrate that systematic KB post-dilatation with NC balloons after provisional SB stenting is associated with favourable procedural results with a low requirement for SB stenting, and promising long-term clinical outcomes.

Conflict of interest statement

D. Mylotte is the recipient of a travelling bursary from Merck Sharp & Dohme. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.