The potential for acute beta-blocker administration to decrease myocardial infarct size, preserve left ventricular function, and improve survival in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) has been investigated for four decades1. In the pre-fibrinolytic era, intravenous followed by oral beta-blockers administered to patients as monotherapy reduced myocardial infarct size and improved survival. In the fibrinolytic era, however, intravenous followed by oral beta-blockers administered as adjunctive therapy did not impact on myocardial infarct size, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), or mortality; however, it did acutely increase the risk for bradycardia, hypotension, heart failure, and cardiogenic shock. Based on this evidence, the American and European STEMI guideline committees gave a Class IIa recommendation for the administration of intravenous beta-blockers at the time of presentation only for patients with hypertension or tachycardia and no signs of heart failure2,3.

Contraindications for beta-blocker administration include bradycardia, hypotension, atrioventricular block, bronchospasm, and heart failure. Clinical exclusions also include cardiac arrest and cardiogenic shock. The early risk with intravenous beta-blocker administration is the negative inotropic effect that can activate subclinical disease and precipitate heart failure or cardiogenic shock. Prudence, therefore, suggests that it is better to wait several hours for most patients with STEMI to stabilise after reperfusion therapy before starting a beta-blocker and to use oral, rather than intravenous, administration after the early risk for harm with acute administration has passed.

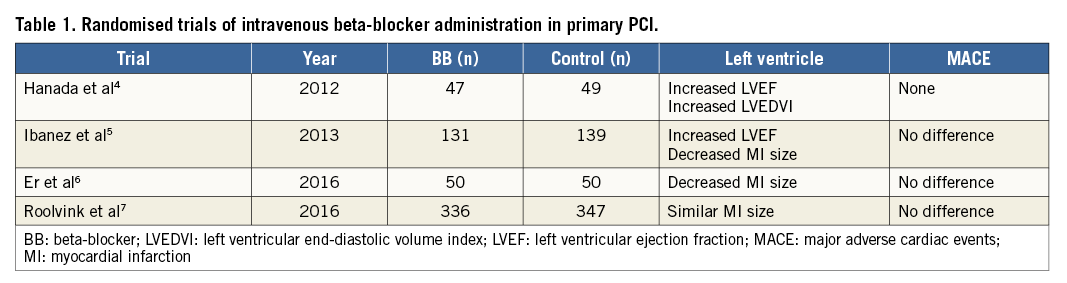

Recently, there have been at least four small randomised trials evaluating the impact of early intravenous beta-blocker administration in patients with STEMI treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)4-7. In contrast to the trials performed with fibrinolytic therapy, three trials suggested improvement in left ventricular function, but the largest trial found no benefit (Table 1). The trials were underpowered to evaluate clinical outcomes which were similar. Two older retrospective cohort analyses of patients undergoing primary PCI suggested that intravenous beta-blocker administration improved left ventricular function and reduced mortality, but there were many differences in baseline characteristics between cohorts suggesting selection bias8,9.

In this issue of EuroIntervention, Mohammad and colleagues compared clinical outcomes with and without intravenous beta-blockers during primary PCI using the national SWEDEHEART registry10.

They enrolled 16,909 patients with STEMI between 2006 and 2013: 2,876 (17.0%) were treated with intravenous beta-blockers. After multivariable adjustment for known confounders, the intravenous beta-blocker cohort had higher 30-day all-cause mortality (HR: 1.44, 95% CI: 1.14-1.83) and in-hospital mortality (HR: 1.23, 95% CI: 0.93-1.61), more in-hospital cardiogenic shock (OR: 1.53, 95% CI: 1.09-2.16), and were more often discharged with an LVEF <40% (OR: 1.70, 95% CI: 1.51-1.92). Propensity score matching and sensitivity analyses supported the results.

It is possible that the harm associated with early intravenous beta-blockers is overestimated in this analysis. The clinical indication for administration was not captured and use declined during the study period, so selection bias may have impacted on the results. For instance, the beta-blocker cohort had longer time to PCI, higher heart rate, higher blood pressure, more atrial fibrillation, more LAD culprit lesions, and larger enzymatic infarct size. Moreover, because this was a retrospective observational database study, residual confounding is another potential limitation. Nevertheless, the conclusion that early intravenous beta-blocker therapy was associated with risk and no benefit is consistent with the results from the fibrinolytic era and with the risk associated with acute beta-blocker administration in the perioperative setting. This study supports current guideline recommendations for very selective intravenous beta-blocker administration in patients with STEMI. The authors state that intravenous beta-blocker use ranges from 2% to 40% in Swedish hospitals, suggesting an opportunity for quality improvement by standardising therapeutic protocols across hospitals to be more consistent with guideline-directed medical therapy. This report should prompt hospitals and STEMI teams to review their use of intravenous beta-blockers in patients with STEMI. The best and only proven strategy to decrease infarct size and improve left ventricular function in patients with STEMI is decreasing time-to-treatment with reperfusion therapy and minimising the early risk for hypotension, heart failure, and cardiogenic shock. Starting oral beta-blocker therapy several hours after reperfusion therapy in stable patients without contraindications gives the patient the hospital benefit of decreasing the risk for recurrent ischaemia and ventricular arrhythmias without the risk of acute haemodynamic compromise. Oral beta-blockers should be continued for a few years in uncomplicated patients for secondary prevention and chronically in patients with heart failure.

Conflict of interest statement

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.