Case summary

Background: A 55 years old man was referred for cardiac transplantation because of intractable angina and fatigue.

Investigation: Physical examination, laboratory test, echocardiography, exercise ECG, MRI and coronary arteriography.

Diagnosis: Multiple coronary artery fistulae.

Management: Beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, ICD.

Keywords: refractory angina pectoris, coronary angiogram, coronary artery fistula, non-compaction cardiomyopathy, and cardiac transplantation.

How should I treat?

Presentation of the case

A 55 year old male was referred for cardiac transplantation because of intractable, incapacitating angina pectoris and severe fatigue. His medical history revealed syncope three years earlier, followed by slowly progressive fatigue and typical anginal chest pain. Angina pectoris was noted after five minutes of walking or climbing one flight of stairs. His estimated functional capacity according the Canadian Cardiovascular Society and the New York Heart Association Classification was class III. His family history was negative for atherosclerotic heart disease or cardiomyopathy and he had one healthy, 23-year old daughter. His cardiologist decided to refer the patient for cardiac transplantation, because evaluation in two other academic centres did not offer other treatment options.

The patient, a lean Dutch male, appeared healthy and had no complaints at rest. Physical examination revealed a resting pulse rate of 70 b/m and blood pressure of 140/70 mm Hg. A “water-hammer” pulse was palpable till his distal lower extremity arteries. A 2/6 systolic and diastolic murmur was heard at the apex and left 4th inter-costal space. There were no signs of heart failure.

His electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm 70 b/m, signs of left atrial dilatation and left ventricular hypertrophy with minor repolarisation abnormalities. A bicycle-exercise test revealed moderately severe impairment of exercise capacity (maximal load 95 Watt or 59% predicted) with 2 mm horizontal ST segment depression at maximal exercise, normalising at the seventh minute of rest, consistent with significant myocardial ischaemia (Figure 1). A 24-hour Holter ECG showed sinus rhythm, without any arrhythmias.

Figure 1. Exercise test showing the ECG at rest, maximal exercise and recovery.

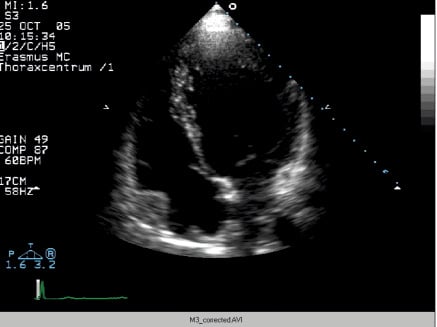

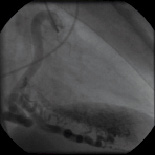

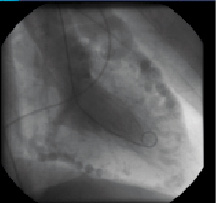

Two-dimensional echocardiography demonstrated mild left ventricular (LV) dilatation (end-diastole 63 mm, end-systole 35 mm), with prominent trabeculae of the left ventricular myocardial walls, not fulfilling the classical criteria for non-compaction cardiomyopathy1. Systolic biventricular function was normal (LV fractional shortening 44%; Figure 2/Movie 1). There were multiple fistulae seen with colour Doppler, at the different levels of the LV walls (Figure 3/Movie 2). Magnetic resonance imaging confirmed the echocardiographic findings, with good systolic LV (EF 73%, cardiac output 8.8 l/min) and RV function and more pronounced abnormal trabeculations. The maximal non-compacted / compacted ratio was 4.4 (Figure 4/Movie 3). The coronary arteries were dilated to an estimated diameter of 8 mm. The flow in the left main coronary artery was 2.8 litres/min (normal: 90 ml/min) and the right coronary artery 1.2 litre/min. There were no signs of myocardial fibrosis on delayed enhancement acquisition. Coronary arteriogram showed severely tortuous and dilated coronary branches as well both the right and the left coronary artery with multiple coronary fistulae draining directly in the LV cavity (Figure 5 and 6/Movies 4 and 5). The shunt fraction was calculated at 2.51. Left ventricular angiography confirmed globally good LV function and retrograde filling of the coronary arteries with partial opacification of the extensive coronary arterial fistulae (Figure 7/Movie 6). There was poor opacification of the coronary sinus, probably due to shunting in to the LV cavity.

The patient’s case was then discussed in our multidisciplinary team with respect to the correct diagnosis, prognosis and treatment options, including cardiac transplantation.

Figure 2 / Movie 1. Apical 4-chamber view at echocardiography, showing mild LV dilatation and good systolic LV function. There are prominent hypertrabeculation at the apical and mid-ventricular myocardial walls, mimicking non-compaction cardiomyopathy.

Figure 3 / Movie 2. Echocardiographic apical 4-chamber view with colour Doppler showing multiple fistulae, at the apical wall.

Figure 4 / Movie 3. Two-chamber magnetic resonance imaging of the LV, showing extensive trabeculation with non-compacted / compacted ratio > 2, fulfilling the Jenni criteria for non-compaction cardiomyopathy2.

Figures 5 and 6 / Movie 4 and 5. Coronary angiogram of the RCA and LCA demonstrating multiple coronary-ventricular fistulae.

Figure 7 / Movie 6. LV angiogram with retrograde filling of the coronary arteries.

How could I treat?

The Invited Experts’ opinion

Typical patients referred to heart transplant (HT) units suffer from advanced heart failure due to severe left ventricular (LV) dysfunction. Major etiologic groups are idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy and ischaemic cardiomyopathy, accounting for 90% of HT recipients1. HT is considered when incapacitating symptoms do not respond to alternative therapies such as drugs, electrical therapies and percutaneous or surgical interventions. Prognosis in these cases may be estimated based on cardiopulmonary stress test and other methods2, and consequently HT is usually indicated in relatively young (<65-70 yrs.) patients without significant comorbidities when the expected survival and quality of life caused by their cardiac disease are below those provided by HT.

Current survival of adult HT recipients 30 days, one year and five years after cardiac replacement is 90%, 80%, 70%, respectively. For patients surviving the first post-HT year, median survival is 13 years, and most of them enjoy good-to-excellent quality of life1. However, life after HT implies a number of drawbacks, including the permanent need of a combination of immunosuppressants for the prevention of acute graft rejection. This therapy is frequently accompanied by significant adverse effects (nephrotoxicity, arterial hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes, GI disturbances, myelodepression, osteoporosis and many others), and also by an increased risk of infection and neoplasia on the long-term. Allograft vasculopathy, a form of chronic rejection affecting both epicardial and microvascular coronary circulation, is the main cause of cardiac morbidity and death among late survivors3,4.

Indication of HT in patients without refractory systolic heart failure is particularly difficult, because there are no validated methods for estimating their prognosis. In our series, only 38 out of 740 HT recipients (5%) had a LV ejection fraction >40%, and only one had refractory angina as the main reason for HT. In this setting, listing for HT is based on an imminent risk of death (e.g., arrhythmic storm), evidence of terminal phase (e.g., signs of cardiac cachexia) or severe, prolonged deterioration of the quality of life (e.g., inability to discharge from hospital, dependence of i.v. inotropes, etc.). Obviously, alternate therapies should always be attempted when judged feasible, and HT will still remain as the last choice.

The patient under consideration shows multiple coronary-cameral fistulae arising from all three major coronary arteries and emptying into LV cavity, a rare entity described as generalised coronary artery-left ventricular (micro)fistulae (GCLVF) by some authors5. In this case, a significant portion of the cardiac output (close to 50%) is diverted back to LV in diastole through multiple fistulae, thus mimicking the physiology of aortic regurgitation. Chronic volume overload has already caused LV dilation, and myocardial damage can be anticipated on the long term. Besides, there is objective evidence of myocardial ischaemia on exertion, a finding previously described in many cases of GCLVF that is attributed to coronary steal phenomenon, with preferential shunting of coronary flow towards LV cavity in diastole5,6. The association of GCLVF with left ventricular non compaction (LVNC) found in this patient is unprecedented, and suggests the persistence of an embryonic pattern in LV wall, in which sinusoid gaps between muscular trabeculae do not disappear because of an impaired process of muscle compaction, thus turning into coronary-LV fistulae6.

Therapeutic options in this case are certainly limited; however, every effort should be made before listing for HT in a patient with preserved LV function and no overt signs of cardiac failure. Our first move would be the initiation or increase of β-blocker therapy (an aspect not detailed in the case report), a measure that could be of help in a patient with exertional symptoms, hyper-dynamic circulation and a heart rate of 70 bpm.

If β-blockade has no significant effect, we would consider the possibility of percutaneous closure of the main fistulous tracts. In the more common setting of a few, large coronary fistulae, many successful procedures with the use of detachable balloons, vascular plugs, covered stents, foam or coils delivered by different methods have been described7. In this case, the presence of numerous, intramyocardial, small size fistulous tracts poses a major technical problem; however, there are precedents of multistage procedures with delivery of coils into distal territories of all three major coronary arteries8. The aid of a vascular interventionalist with experience in the treatment of vascular malformations of the CNS (somewhat similar to this type of lesions) may prove invaluable in the planning and performance of these procedures.

If everything fails, HT would be an excellent option for this patient without obvious contraindications, with the benefits and risks exposed at the beginning of this comment.

How should I treat?

An unusual referral for heart transplantation

Coronary artery fistulae are the most common form of haemodynamic significant coronary artery abnormalities. They can originate from anywhere in the coronary artery system and can terminate in any cardiac chamber, or a major vein or the pulmonary arteries. Significant coronary artery fistulas are rare as compared to minor or incidental coronary fistulas, which are seen in over 75% of cases and almost all drain into the right side. The majority originate from the left coronary artery (~55%) with multiple fistulas occurring in only ~8% of cases1. Over 90% of fistulae drain into the right side with drainage into the left ventricle being the least common. Coronary fistulas that drain into the right side of the circulation create a left-to-right shunt of oxygenated blood back to the pulmonary circulation. Whereas coronary artery fistulas that drain into the left ventricle produce haemodynamic changes similar to aortic incompetence. Also, in addition to the volume overload on the heart, coronary artery fistula can result in coronary artery “steal” a phenomenon in which coronary blood preferentially passing through the fistula bypassing the more distal myocardium capillary beds that supply the myocardium (stealing blood). Clinical presentations are dependent on the type of fistula, shunt volume, site of the shunt, and presence of other cardiac conditions. Symptomatic patients present with angina, arrhythmia or other signs of congestive heart failure as was the case in the patient presented by Dr. Caliskan.

Caliskan et al’s patient has bilateral coronary artery fistulae (left and right coronary arteries) draining into the left ventricle. The coronary arteries are diffusely dilatated and tortuous, reaching >8 mm in diameter. The left ventricle (LV) function is normal however, stress test is positive. The options that must be considered are could a percutaneous closure or a surgical closure be achieved.

There are several centres with extensive experience in catheter device closure. Different devices (balloons, plugs, coils and other occluding devices) have been developed but still struggle with vessel tortuosity, optimal catheter delivery and residual or recurrent leaks. However, due to the presence of multiple drainage sites, the interventional option is impossible at this time. The surgical repair has a low mortality (<1%)2 when a single coronary artery fistula is concerned, but in the patient presented, surgical correction would not be possible due to multiple sites of drainage and all coronary arteries being involved.

The clinical management is obviously challenging in this case, because of the large size of the fistulas, tortuosity, and all coronary arteries are involved, therefore, we believe the best treatment is cardiac transplantation, which has a survival rate of 85% to 90% at one year3,4.

How did I treat?

Actual treatment and management of the case

Given the pan-cardiac character of the coronary-ventricular fistulae without a history of other diseases or trauma, we postulated that the aetiology was congenital. Therefore, his 23-years old daughter was screened. She was asymptomatic, with normal exercise capacity, ECG, and normal two-dimensional echocardiography.

In early foetal development, the primitive loosely packed myocardium is nourished via sinusoids. As the myocardium becomes more compact, the sinusoids disappear and give rise to a network of veins, arteries, and capillaries. Persistence of these connections may result in coronary artery fistulae. Microscopic foci of persistent embryonic spongy myocardium may be seen, probably explaining the non-compaction cardiomyopathy look-a-like in our case1-3. Congenital coronary fistulae communicating with the left ventricle are very rare and usually single. The right coronary artery seems to be affected more frequently than the left. Multiple coronary-ventricular fistulae affecting all three major coronary arteries are extremely rare4. Most coronary artery fistulae are small without compromising the myocardial blood flow and give no symptoms. However, with increasing shunting, and probably with increasing age (like in our case), a coronary artery steal syndrome develops with resultant ischaemia and volume overload. Patients with a coronary artery fistulae are commonly identified because of the associated loud, continuous fistula murmur. Other clinical presentations include angina, arrhythmias, and heart failure due to chronic volume overload6,7.

In our case, since the coronary arterial fistulae were extremely numerous and affecting the whole heart, neither surgery nor transcatheter coil closure seemed a reasonable option. As the patient also had excellent systolic left ventricular function, we felt that the option of cardiac transplantation was not the preferred treatment option at this time. We treated the patient with a beta-blocker, to slow his heart rate and decrease the oxygen demand of the heart. Thereafter, we started angiotensin converting enzyme-inhibitor, to unload the pre- and afterload of the LV, since we hypothesised that the numerous coronary-cameral fistulae would give chronic left-sided volume overload. Finally, we hypothesised that the patient was at high risk for sudden cardiac death because of ischaemia at exercise and a history of unexplained syncope. Therefore, an ICD was implanted prophylactically.

At three months of follow-up, angina was infrequent and exercise tolerance significantly improved. His estimated CCCS functional was class I and NYHA class II. The measured exercise capacity improved to 130 W (75% predicted) with a peak VO2 uptake of 24.7 ml/min/kg.

At five years of follow-up, the patient was only mildly symptomatic, without any cardiac event or hospital admissions. His echocardiogram showed improved LV dimensions (end-diastolic 50 mm and end-systolic 36 mm) with excellent systolic function.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.