ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) results from a complete coronary obstruction by an acute thrombosis secondary to atherosclerotic plaque rupture or erosion. The subsequent exposure of collagen and von Willebrand factor leads to local vasoconstriction and platelet activation; this phenomenon is self-sustained by continuous interplatelet recruitment with expression of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa and the local release of thromboxane A2, adenosine diphosphate and thrombin. The resulting platelet plug - the first step of the physiological haemostasis process - then catalyses thrombin formation allowing fibrinogen molecules to polymerise into a fibrin mesh – the clot framework - enabling its growth and stabilisation. When the trigger is too powerful, normal haemostasis shifts to an undesirable pathological process that is complete acute coronary thrombosis. Stopping this dreadful situation requires fast-acting and efficient antithrombotic therapy to allow the natural fibrinolysis process to take place, to facilitate coronary reperfusion and, in particular, to facilitate primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), which is itself prothrombogenic.

As the most affordable and oldest anticoagulant, unfractionated heparin (UFH) is the most used and preferred drug in STEMI. UFH is a sulphated muco-polysaccharide with a molecular weight ranging from 4,000 to 30,000 Daltons that binds with antithrombin III and enables a direct inhibition of thrombin and factor Xa. Of note, the inhibition of factor Xa prevents the activation of prothrombin into thrombin, and hence prevents the formation of fibrin and thrombus stabilisation. Apart from pilot studies such as HEAP (Heparin in Early Patency), which demonstrated a high rate of success for primary PCI when UFH is used in STEMI1, most of the evidence of the potential benefit of UFH has been provided by trials which enrolled medically managed patients with unstable angina or non-ST-segment elevation MI. Despite the lack of contemporary data, the use of UFH is highly supported in both American and European guidelines23.

In the analysis of the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR) presented by Emilsson et al in this issue of EuroIntervention, only 38% of the 41,631 patients who presented with STEMI were treated with UFH before arriving at the cath lab4. The investigators demonstrated the association between pretreatment with UFH and success of reperfusion (number needed to treat [NNT] 12) and reduction in mortality (NNT 94). Importantly, pretreatment with UFH was not associated with an increase in bleeding events. Investigators used two different statistical methods – Poisson regression models and propensity score-matched groups – with consistent results except for mortality for which the reduction was significant only with the Poisson regression models. The authors are to be commended for this work; their observations extend beyond the conclusion that pretreatment with UFH works in STEMI to involve the general organisation of care systems and the implementation of strategies, which is the primary goal of registries such as SCAAR. While it is intriguing that pretreatment with UFH was only delivered to one out of three patients with STEMI, we could observe that this proportion increased from 26% in 2008 to 49% in 2016 and is probably much more frequent in 2022; furthermore, secondary centres more frequently missed the opportunity to administer UFH in patients with STEMI, despite involving transfers with longer times before reperfusion. Importantly, patients who did not receive UFH pretreatment presented more often with high-risk features: more frequent prior MI, kidney failure, peripheral vessel disease and cardiogenic shock. This highlights the paradox of more severity leading to less active treatment with antithrombotic therapy due to the fear of adding harm, despite UFH being rapidly efficient with a short half-life, and easily reversible.

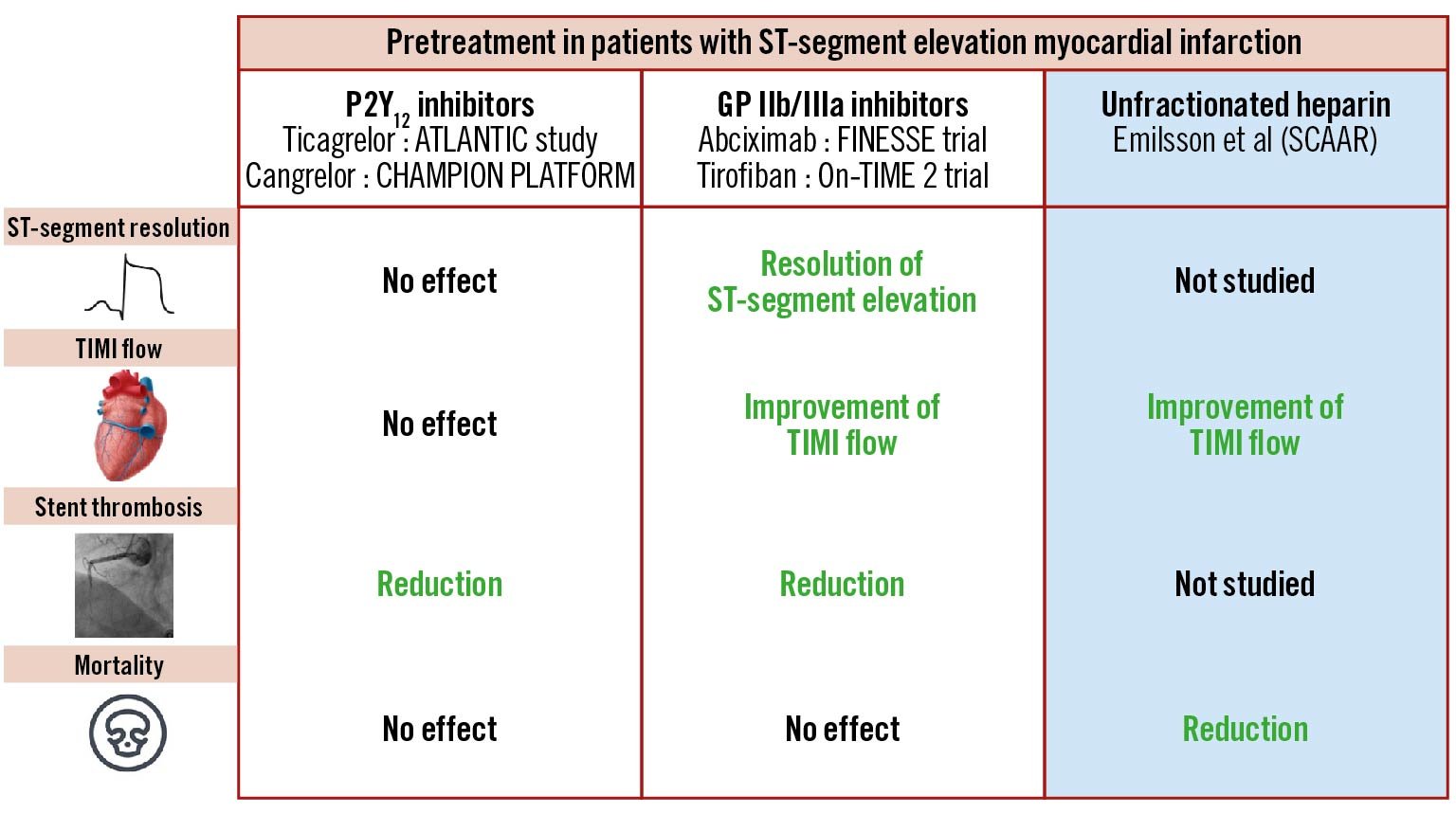

More trials are needed to better understand which antithrombotic agent should be administered as soon as possible when a complete coronary occlusion is suspected. Potent drugs with a fast onset of action such as heparin have often been associated with reperfusion success and better outcomes5(Figure 1). In a post hoc analysis of the TASTE (Thrombus Aspiration in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction in Scandinavia) trial, pretreatment with heparin was associated with a 27% risk reduction of intracoronary thrombus and 36% risk reduction of total vessel occlusion – without an increase in bleeding events6. A previous Spanish study already demonstrated that early administration of UFH in patients requiring transfer for primary PCI increased reperfusion success by 60%, with a significant impact on 1-year survival7. Before the advent of potent oral P2Y12 inhibitors, similar observations were made when pretreating with intravenous glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors although the survival benefit was inconsistent across trials8910. Contemporary studies comparing pretreatment with crushed oral P2Y12 inhibitors versus with regular tablets demonstrated a consistently faster onset of platelet inhibition without any effect on complete ST resolution or Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 3 flow prior to PCI, suggesting the inability of these drugs to dissolve a stabilised occlusive thrombus. Overall, these findings further highlight the early coagulation cascade blockade as being critical to clot dissolution.

Figure 1. Pretreatment with antithrombotic treatment in STEMI patients. The potential benefits of an early administration of various antithrombotic treatments is depicted. GP IIb/IIIa: glycoprotein IIb/IIIa; SCAAR: Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction

There are some limitations to this study. First, activated clotting time monitoring may have likely improved the results. Second, it is not randomised, and even if statistical adjustments have been performed meticulously, confounding factors may persist. Third, the reported benefits of pretreatment with heparin may have been counterbalanced by the increasing frailty of the STEMI population, often polymedicated and with a high bleeding risk, and also by using new-generation stents that are less vulnerable to thrombosis.

Stronger evidence should emerge from the ongoing randomised UFH-STEMI (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05247424) trial comparing final TIMI flow in 600 patients with early UFH administration at first medical contact versus during coronary angiography. By then, the definition of pretreatment will have shifted from medical to an earlier self-administration of drugs. The SOS-AMI (Selatogrel Outcome Study in Suspected Acute Myocardial Infarction) randomised study is currently evaluating a strategy of selatogrel self-injection in 14,000 individuals with known coronary artery disease who experience chest pain suggestive of myocardial infarction (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04957719). While awaiting the results of these trials, the present analysis by Emilsson et al suggests that earlier is better with regard to anticoagulation for STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI. The pending question is when to stop when there is no compelling indication for continuation.

Conflict of interest statement

J-P. Collet reports lecturing fees from AstraZeneca, Boston Scientific, Bristol-Myers Squibb, COR2ED, Lead-Up, and WebMD; and grants from Medtronic and BMS/Pfizer. M. Zeitouni has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.