Abstract

Aims: We sought to assess the proportion of patients eligible for the ISCHEMIA trial and to compare the characteristics and outcomes of these patients with those without ISCHEMIA inclusion or with ISCHEMIA exclusion criteria in a contemporary, nationwide cohort of patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD).

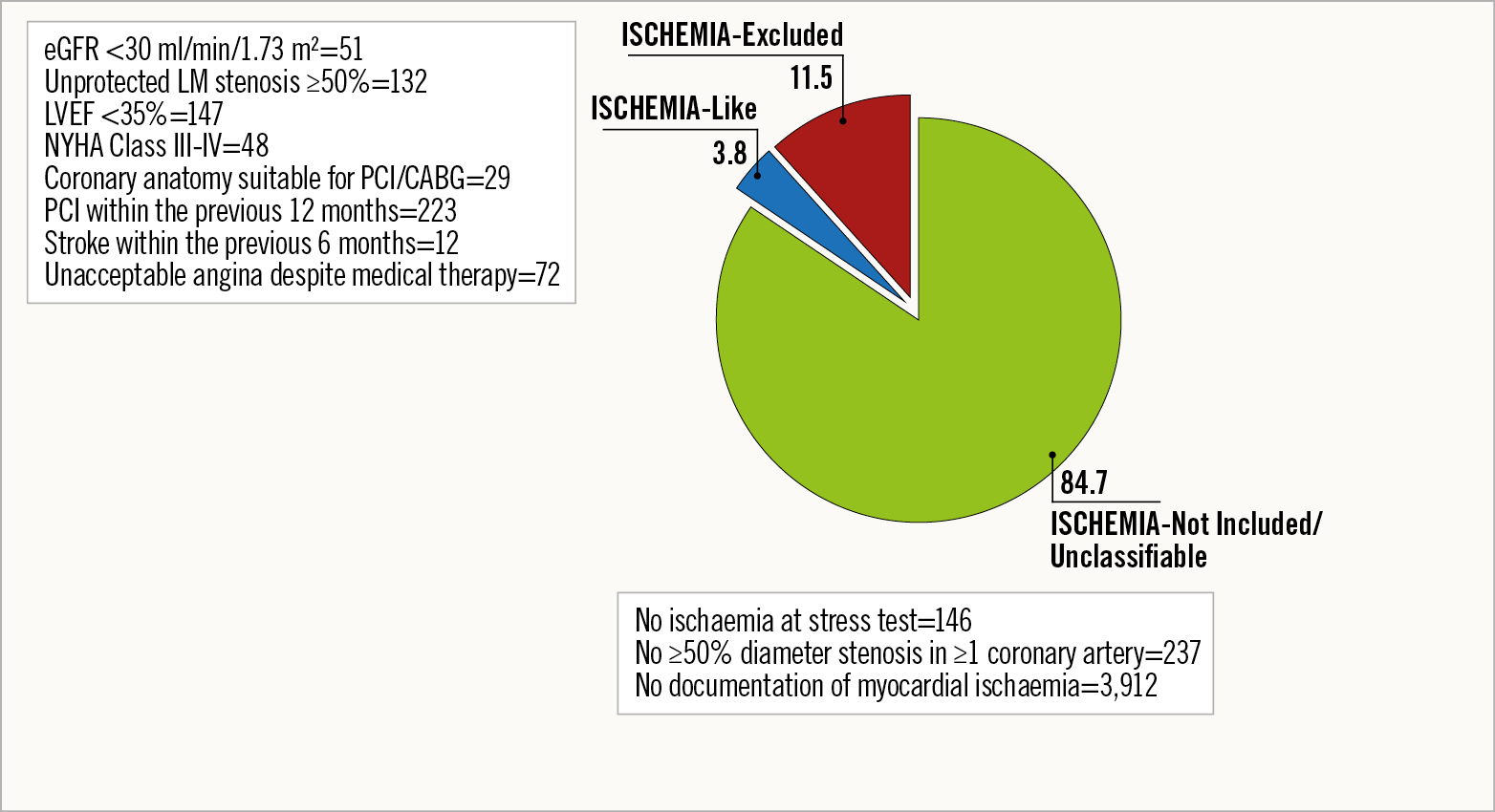

Methods and results: Among the 5,070 consecutive patients enrolled in the START registry, 4,295 (84.7%) did not fulfil the inclusion criteria (ISCHEMIA-Not Included or ISCHEMIA-Unclassifiable), 582 (11.5%) had exclusion criteria (ISCHEMIA-Excluded), and the remaining 193 (3.8%) were classified as ISCHEMIA-Like. At one year, the incidence of the primary outcome, a composite of death from cardiovascular (CV) causes, myocardial infarction (MI), or hospitalisation for unstable angina and heart failure, was 0.5% in the ISCHEMIA-Like versus 3.3% in other patients (p=0.03). The composite secondary outcome of CV mortality and MI occurred in 0.5% of the ISCHEMIA-Like patients and in 1.4% of the remaining patients (p=0.1).

Conclusions: In a contemporary real-world cohort of stable CAD patients, only 4% resulted in being eligible for the ISCHEMIA trial. These patients presented an extremely low annual risk of adverse events, especially when compared with other groups of stable CAD patients.

Visual summary. Proportion of patients with stable CAD enrolled in the START registry with or without ISCHEMIA criteria and their rate of MACE at 1 year.

Introduction

Recently, the International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness with Medical and Invasive Approaches (ISCHEMIA) trial demonstrated that an initial invasive strategy did not decrease the incidence of cardiovascular (CV) events or death from any cause compared to optimal medical therapy (OMT) alone, in patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD) and moderate to severe myocardial ischaemia1. Based on these data, stable CAD patients who fit the ISCHEMIA profile and do not have unacceptable levels of angina may be treated with an initial conservative strategy1,2.

Patients included in clinical trials are usually highly selected and do not have the same risk level faced in daily practice3. Therefore, the translation of evidence from randomised clinical trials to contemporary clinical scenarios is essential for healthcare systems3.

Using the data from the nationwide STable Coronary Artery Diseases RegisTry (START) study4,5, we sought to assess the proportion of ISCHEMIA eligible patients in a contemporary cohort of patients with stable CAD managed by cardiologists in daily clinical practice. In addition, we compared the characteristics and outcomes of ISCHEMIA eligible patients with those without inclusion or with exclusion criteria of the ISCHEMIA trial in a real-world setting.

Methods

The design and the main results of the START registry have been published previously4. Briefly, START was a prospective, observational, nationwide study endorsed by the Italian Association of Hospital Cardiologists (ANMCO) and aimed at evaluating the current presentation, management and treatment of patients with stable CAD as seen by cardiologists in clinical practice in Italy4. Patients with stable CAD presenting to a cardiologist during an outpatient visit or those discharged from cardiology wards were eligible if they had at least one of the following clinical conditions: (1) typical or atypical stable angina and/or non-anginal symptoms; (2) documented ischaemia at stress test with or without symptoms; (3) previous revascularisation, such as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG); (4) prior episode (occurring at least 30 days from enrolment) of acute coronary syndrome (ACS); and (5) elective admission for coronary revascularisation (including staged procedures). We excluded patients aged <18 years and those with Canadian Cardiovascular Society class IV angina or with atypical chest pain that in all probability was not related to CAD4.

Data on baseline characteristics, including demographics, risk factors and medical history, and information on the use of diagnostic cardiac procedures, type and timing of revascularisation (if performed) and use of pharmacological or non-pharmacological therapies were recorded on an electronic case report form (CRF) at hospital discharge or the end of an outpatient visit4,5.

Patients receiving OMT were defined as those being prescribed aspirin or thienopyridine, β-blockers, and statins, at the maximum tolerated dosage6,7. To be categorised as receiving OMT, individual patients must either have been prescribed or have reported contraindications to all medications in each category4. Data on the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) were recorded and could be used to calculate their use among those patients in whom they were clinically indicated. Therefore, given that the guidelines for the management of stable CAD6,7 recommend an ACE-I or ARB for some subgroups of patients, we also examined patients receiving OMT, defined as those being prescribed aspirin or thienopyridine, β-blockers, statins and ACE-I or ARB, if indicated by an ejection fraction ≤40%, hypertension, diabetes or chronic renal dysfunction (eligible patients).

ANMCO invited all Italian cardiology wards to participate, including university teaching hospitals, general and regional hospitals, and private clinics receiving patients with stable CAD. No specific protocols or recommendations for evaluation, management, and/or treatment were mandated during this observational study. However, guidelines for the management of patients with stable CAD were discussed during the investigator meetings4.

All patients were informed of the nature and aims of the study and asked to sign an informed consent for the anonymous management of their individual data. Local institutional review boards (IRB) approved the study protocol according to the current Italian rules.

One hundred and eighty-three (183) cardiology centres included consecutive patients in the survey in different periods of three months between March 2016 and February 2017 (Supplementary Appendix 1),4.

DEFINITIONS OF ISCHEMIA POPULATIONS

The main ISCHEMIA inclusion and exclusion criteria1,8 were applied to the START population.

Patients with stable CAD <21 years old with no documentation of myocardial ischaemia at stress test were included in the “ISCHEMIA-Not Included/Unclassifiable” subset.

Patients meeting any ISCHEMIA exclusion criteria1,8, such as estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 ml per minute per 1.73 m2 of body surface area, a recent (<2 months) ACS, unprotected left main stenosis of at least 50%, a left ventricular ejection fraction of <35%, New York Heart Association Class III or IV heart failure, and unacceptable angina despite the use of medical therapy at maximum acceptable doses1,8, were excluded (the “ISCHEMIA-Excluded” subset).

Patients were included in the “ISCHEMIA-Like” subset if they had no exclusion criteria, fulfilled the ISCHEMIA inclusion criteria (patients ≥21 years old and with reversible ischaemia on imaging or stress tests) and presented at least 50% stenosis in at least one major coronary artery within six months of enrolment (anatomic eligibility criteria of the ISCHEMIA trial)1,8.

In the present analysis, we compared the characteristics and outcomes of ISCHEMIA-Like versus ISCHEMIA-Not Included/Unclassifiable and ISCHEMIA-Excluded patients.

CLINICAL EVENTS AND FOLLOW-UP

The primary outcome of the present analysis was the occurrence of major adverse CV events (MACE), a composite of death from CV causes, MI, or hospitalisation for unstable angina and heart failure at one-year follow-up. The secondary outcome was a composite of CV mortality and MI at one year. Myocardial infarction was defined according to the third universal definition of MI9.

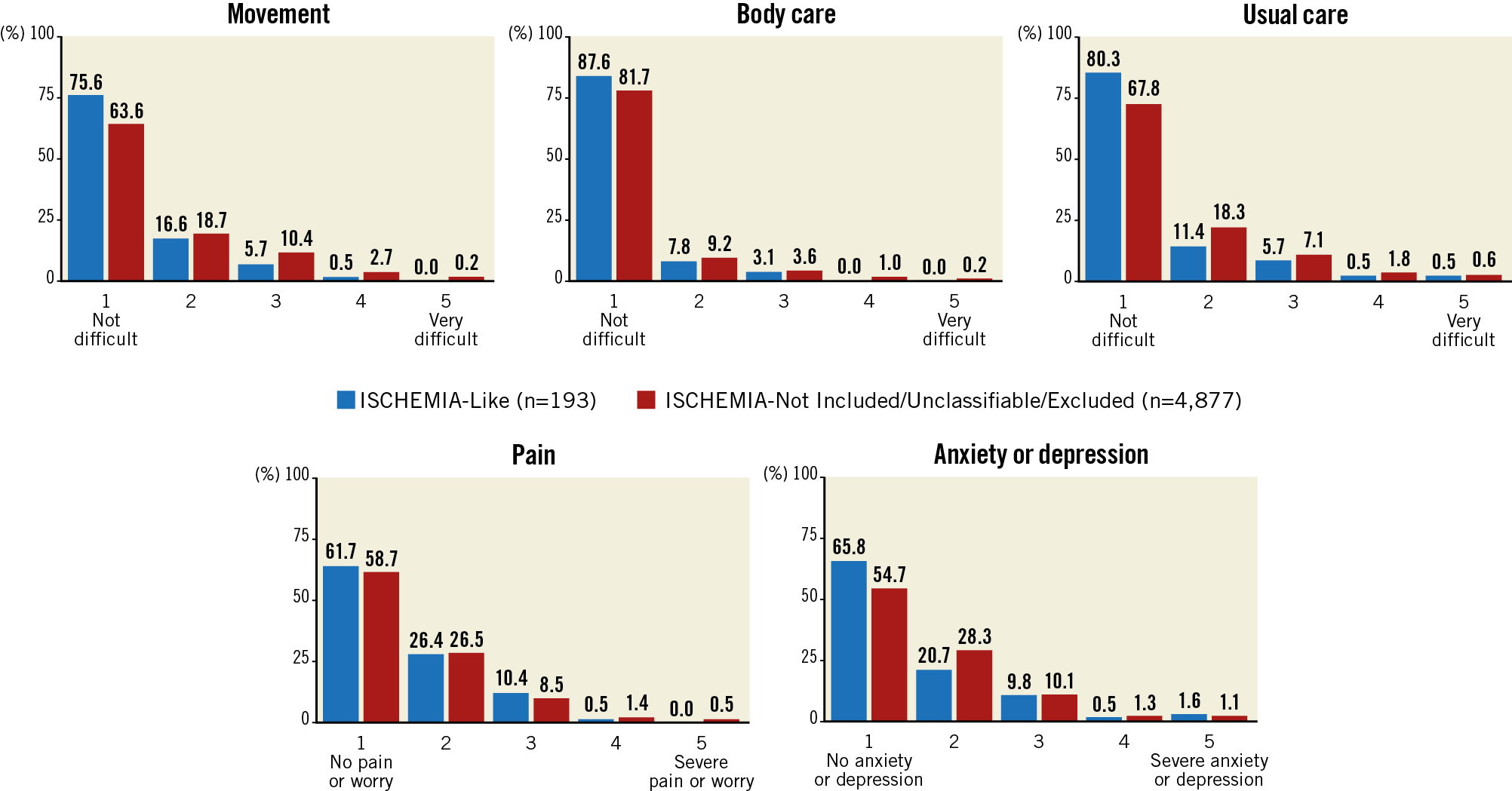

All patients were followed up by visits or telephone interviews by investigators. Interviews included questions related to the occurrence of events, planned and unplanned hospitalisations. In addition, all patients were asked to complete the self-administered EuroQol-5D-5L (EQ-5D-5L) quality of life (QoL) questionnaire10, comprising a visual analogue scale (VAS) of self-rated general health and five dimensions (mobility, self-care, daily activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). Scores on the VAS range from 0 (worst state) to 100 (best state). Scores in the five dimensions can be expressed as the percentage of patients who indicate one of the five levels of severity in each dimension.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages and compared by the chi-square test. Continuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD), except for laboratory variables, which are reported as median and interquartile range (IQR). Continuous variables were compared by the analysis of variance (ANOVA), if normally distributed, or by the Kruskal-Wallis test, if not. Propensity score modelling was used to perform a one-to-one matching using all baseline covariates without missing data, leading to a population of 193 matched patients for each group. Kaplan-Meier methods were used to construct unadjusted curves for the primary outcome over one year and log-rank tests were performed to evaluate differences between groups. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All tests were two-sided. Analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Among the 5,070 consecutive stable CAD patients enrolled in the START registry, 4,295 (84.7%) were classified as ISCHEMIA-Not Included/Unclassifiable, 582 (11.5%) as ISCHEMIA-Excluded, and the remaining 193 (3.8%) as ISCHEMIA-Like (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Proportion of ISCHEMIA-Like, ISCHEMIA-Not Included or Unclassifiable and ISCHEMIA-Excluded patients within the START population.

Baseline characteristics of patients in two groups (ISCHEMIA-Like and ISCHEMIA-Not Included/Unclassifiable/Excluded) are shown in Table 1. ISCHEMIA-Like patients presented a lower rate of risk factors such as malignancy, history of atrial fibrillation, heart failure or myocardial revascularisation and a higher mean left ventricular ejection fraction compared to those in the other group (Table 1).

Among the 4,409 (87.0%) patients with coronary angiography data available, those deemed as ISCHEMIA-Like presented a higher incidence of single-vessel CAD compared to other patients (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Extension of CAD (among the 4,409 patients with data available) in the ISCHEMIA-Like and ISCHEMIA-Not Included/Unclassifiable/Excluded groups.

At the time of discharge/end of the visit, patients in the ISCHEMIA-Like group received more aspirin but fewer beta-blockers, diuretics, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist and oral anticoagulant agents compared to ISCHEMIA-Not Included/Unclassifiable/Excluded patients (Supplementary Table 1). Notably, the rate of OMT (in both the overall and eligible populations) was similar between the two groups (Supplementary Table 1).

CLINICAL EVENTS AND QoL AT FOLLOW-UP

At one year (median 369; IQR 362-378 days) from enrolment, the incidence of the primary composite outcome was 3.3% in the ISCHEMIA-Not Included/Unclassifiable/Excluded group, and 0.5% in the ISCHEMIA-Like group (p=0.03). The Kaplan-Meier curves of the events included in the primary endpoint for the two groups are shown in Figure 3. Supplementary Table 2 shows the incidence of the individual components of the primary endpoint for each group. The composite secondary outcome of CV mortality and MI occurred in 1.4% and 0.5% of ISCHEMIA-Not Included/Unclassifiable/Excluded patients and ISCHEMIA-Like patients, respectively (p=0.1). After propensity score matching, the primary outcome occurred in 1 out of 193 patients (0.5%) in each group (p=1.0). The rates of primary and secondary outcomes according to the number of diseased coronary vessels in the two groups are shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the primary composite outcome in the two groups.

Supplementary Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier curves of 223 coronary revascularisation procedures (10 in the ISCHEMIA-Like and 213 in the ISCHEMIA-Not Included/Unclassifiable/Excluded group) performed during the follow-up. Among these procedures, 185 were elective (10 in the ISCHEMIA-Like group and 175 in the ISCHEMIA-Not Included/Unclassifiable/Excluded group).

The EQ-5D-5L questionnaire was completed by 4,853 (96%) patients. The median VAS score of self-rated general health status was 75 (IQR 60-85). Over 60% of patients reported having “no problems” in all EQ-5D-5L dimensions (61.1-88.1%), except for pain/worry and depression/anxiety, which were present, to different degrees, in at least 51% of patients in the ISCHEMIA-Not Included/Unclassifiable/Excluded group. The single dimensions with the five levels of severity in each domain are shown in Figure 4 and did not differ between the two groups.

Figure 4. Single dimensions of the EuroQol-5D-5L questionnaire in ISCHEMIA-Like and ISCHEMIA-Not Included/Unclassifiable/Excluded patients.

Discussion

The major results of the present analysis of a large, nationwide, contemporary registry of stable CAD were the following: 1) patients who fulfil all criteria for enrolment in the ISCHEMIA trial represent a very small fraction of the population; 2) ISCHEMIA-Like patients present a low annual risk of MACE and a good QoL, especially if compared with those not eligible for the ISCHEMIA trial.

The ISCHEMIA trial failed to demonstrate that an initial invasive strategy, in addition to OMT, reduces adverse ischaemia-related events as compared with an initial conservative strategy, with catheterisation and revascularisation reserved for failure of OMT, in patients with stable CAD with at least moderate ischaemia on stress testing1. The background of the ISCHEMIA trial was based on the observation that the extent and severity of ischaemia could be associated with an increased risk for death and MI, and that revascularisation could improve prognosis in the presence of large areas of myocardial ischaemia11,12. However, patients included in prior studies did not receive pharmacological agents that are currently known to improve clinical outcomes, while in ISCHEMIA there was a high rate of use of OMT that might have changed the prognosis of patients randomised to a conservative strategy1,13,14. In our analysis, the rate of OMT was above 65% without significant differences between groups, confirming the quality of the START registry.

The purpose of the present analysis was not to replicate the ISCHEMIA trial results in a real-world context but to evaluate the applicability of the ISCHEMIA results among consecutive CAD patients managed by cardiologists during ambulatory visits. In this context, although the results of the ISCHEMIA trial could impact on clinical practice and change the indication to coronary revascularisation in stable CAD, its external applicability in our contemporary cohort seems poor. Indeed, the rate of ISCHEMIA-Like patients in our cohort was extremely low. This finding may be related to the fact that most of our stable CAD patients did not undergo any test for the evaluation of inducible ischaemia before enrolment and then resulted in not being eligible according to the ISCHEMIA criteria. However, even if current guidelines suggest that patients with a moderate to high likelihood of CAD should be triaged by a non-invasive test for ischaemia6,7, several observational studies demonstrated that, in accordance with our series, this recommendation is frequently disregarded in clinical practice15,16. Moreover, it should be noted that our findings showing a low external applicability of the ISCHEMIA trial are consistent with its low enrolled/screened ratio for potential eligibility based on the level of ischaemia (around 20%) and a 25% crossover of patients initially treated conservatively to myocardial revascularisation1,13.

Among the ISCHEMIA-Like patients enrolled in our registry, we observed a low incidence of clinical events at one year. Although the definition of the primary outcome of our analysis is comparable to the primary endpoint of the ISCHEMIA trial1, any comparison between our clinical data at follow-up and trial findings should be considered speculative, especially if the different risk profiles of the enrolled patients and the different lengths of follow-up are considered. Indeed, we assessed the natural history of ISCHEMIA-Like patients who underwent a revascularisation, if any, a few months before enrolment and were managed by cardiologists mainly during outpatient visits. In this regard, the incidence of periprocedural MI, that drove the endpoints and the large difference in event rates between invasive and conservative groups in early follow-up of the ISCHEMIA trial1, has not been considered in our analysis. On the other hand, the yearly rate of spontaneous MI, defined according to the third universal definition of MI in both ISCHEMIA and START1,4, was low both in the trial and in the present series.

Compared to the baseline characteristics of patients randomised in the ISCHEMIA trial1,13, our ISCHEMIA-Like population was older (median age 67 vs 64 years old) and presented a higher incidence of prior MI (53% vs 19%) and revascularisation (61% vs 25%) but less diabetes (29% vs 42%) and three-vessel CAD (12% vs 40%) (Supplementary Table 3). This latter difference may be explained by the fact that eligibility for randomisation by non-imaging exercise tolerance tests in the ISCHEMIA trial required a documented ≥70% stenosis in a major non-left main coronary artery1,8. As a result, most patients randomised in the ISCHEMIA trial had an extensive anatomic CAD. This finding may further explain the difference observed at one year in adverse clinical events between the ISCHEMIA trial and our ISCHEMIA-Like population. Indeed, within the ISCHEMIA trial, recurrent ischaemic events and prognosis were related more to the extent of CAD than to other determinants such as the degree of inducible ischaemia1, consistent with some previous reports17.

Most ISCHEMIA participants had mild-to-moderate angina at baseline, 35% had no angina and only 44% had angina several times per month1,13,18. Thus, to a great extent, ISCHEMIA reflected a population with no or only minimal symptoms18. Even in our real-world registry, approximately 40% of ISCHEMIA-Like patients did not present angina at enrolment and reported elevated scores in all EQ-5D-5L dimensions, reflecting a more than satisfactory QoL.

Study limitations

Our study must be evaluated in the light of some limitations. First, it suffers the same limitations as all observational non-interventional studies with differences from the standardised treatment regimen of a randomised trial. In addition, we did not use monitoring of all records from all sites. Therefore, comparisons and differences should be interpreted with caution. Second, in the ISCHEMIA trial, only patients with a clinically indicated stress testing showing moderate or severe reversible ischaemia on imaging tests or severe ischaemia on exercise tests without imaging could be included1. In the START registry, the indication for the stress test and the degree of ischaemia were not collected. Therefore, ISCHEMIA-Like patients included in our survey might be at lower risk and their rate could be overestimated, as compared to those enrolled in the ISCHEMIA trial. Third, the primary endpoint of the ISCHEMIA trial included resuscitated cardiac arrest1. This event was not collected in our registry. However, this condition rarely occurred in the ISCHEMIA trial and had a negligible impact on the primary endpoint1. Fourth, in the present analysis the anatomical eligibility and the extent of CAD were based on coronary angiography performed within six months from enrolment. Therefore, we cannot exclude that, if there was a worsening of the CAD over time, this may have influenced the outcomes. Fifth, we used the third universal definition of MI, which requires a much lower biomarker threshold to diagnose a periprocedural MI than the primary definition used in the ISCHEMIA trial. However, only for procedural MI, the ISCHEMIA investigators used a secondary definition that considered biomarker thresholds that were similar to those of the universal definition but with additional criteria based on elevations of biomarker levels alone1. Nevertheless, the different definition of periprocedural MI used in our registry does not seem to have impacted on the important differences in the relative rates of MI observed between the ISCHEMIA-Like and the other group of patients. In addition, the median follow-up of one year (compared to 3.2 years in ISCHEMIA) does not allow statements to be made about long-term outcomes. Finally, the population of the START registry represents a nationwide sample in Italy and cannot necessarily be extrapolated to other countries.

Conclusions

In a contemporary real-world cohort of patients with stable CAD, 96% resulted in being non-eligible or excluded and 4% as eligible according to ISCHEMIA criteria. In current clinical practice, the inclusion criteria used in the ISCHEMIA trial defined a population with a low risk of adverse clinical events and a good QoL. Further studies are required to confirm the ISCHEMIA trial results in a real-world patient population.

|

Impact on daily practice In current clinical practice, patients who fulfil all criteria for enrolment in the ISCHEMIA trial represent a very small fraction of patients with stable coronary artery disease. ISCHEMIA-Like patients present a low annual risk of adverse clinical events and a good quality of life, especially if compared with those potentially not eligible for the ISCHEMIA trial. |

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.