During the last decade, there has been a mounting tension between how physicians interpret scientific evidence derived from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and the rapidly expanding sources of digitised data that comprise observational studies, registries and, more recently, machine learning and artificial intelligence that are now commonly referred to as real-world data (RWD) or real-world evidence (RWE)1,2,3. Many regard such non-randomised observational analyses of large electronic patient databases as an alternative to RCTs and as a valid and worthy source of RWE. Apart from the prevalent view that traditional, large, multicentre RCTs have become too complex, costly, and selective, another inevitable barrier of translational research is bridging the so-called “T2 gap” – the temporal lag of translating results from research studies into everyday clinical practice and health decision making4. It is frequently estimated that it takes an average of 17 years for research evidence both to influence guidelines and to reach the clinical practice ecosystem5.

While rigorously designed and executed prospective RCTs provide the highest level of scientific evidence to establish the causal relationship between an intervention and subsequent population-level outcomes (known as “internal validity”), they do not, as compared with RWD/RWE data sources, always yield relevant information about the effects in a particular target population (known as “external validity”)6,7. Thus, there is an important need to replicate and validate trial-based evidence in the larger universe of unselected patient cohorts.

Against this backdrop, the provocative paper by De Luca and co-workers8 in this issue of EuroIntervention addresses how findings from the large International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness with Medical or Invasive Approaches (ISCHEMIA)9 compare to a large registry of stable coronary artery disease (CAD) patients in whom the authors modelled their analysis using the same inclusion and non-inclusion criteria to assess the external validity of the trial and observed clinical outcomes in a comparably sized observational database.

Among 5,070 consecutive patients enrolled in the Italian nationwide STable Coronary Artery Diseases RegisTry (START), 4,295 subjects (84.7%) did not fulfil the ISCHEMIA inclusion criteria (defined as “ISCHEMIA-Not Included” or “Unclassifiable”), 582 registry patients (11.5%) met ISCHEMIA exclusion criteria (the “ISCHEMIA-Excluded” subset), and the remaining 193 subjects (only 3.8%) were classified as “ISCHEMIA-Like”. At one year, the incidence of the primary outcome, a composite of cardiovascular (CV) death, myocardial infarction (MI), or hospitalisation for unstable angina and heart failure, was just 0.5% in the “ISCHEMIA-Like” START registry patients as compared with 3.3% in other patients (p=0.03). The composite secondary outcome of CV mortality and MI occurred in just 0.5% of the “ISCHEMIA-Like” START patients and 1.4% of the remaining patients (p=0.1). Quality of life (QoL) in START, assessed using the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire, was completed in 96% of patients, with a median self-rated general health status score of 75, which compares quite similarly to the Seattle Angina QoL score as used in ISCHEMIA. Thus, this contemporary RWE cohort of stable CAD patients showed that about 96% of subjects would have been classified as “non-eligible or excluded” and less than 4% as “ISCHEMIA-eligible”, and that this defined a population at extremely low risk of adverse clinical events and a good QoL at one year.

While several RCTs and meta-analyses since 200010,11,12,13,14 have shown that an invasive strategy with revascularisation when added to optimal medical therapy (OMT) does not reduce the subsequent rate of death or MI compared with OMT alone during long-term follow-up, ISCHEMIA was designed to test the hypothesis that higher-risk patients with moderate-severe baseline ischaemia would have a lower cardiac event rate with revascularisation, fuelled largely by older observational data that the extent and severity of ischaemia was associated with an increased risk for death and MI for which revascularisation could improve prognosis15. However, ISCHEMIA showed no difference between invasive and conservative strategies for both the 5-component primary and 2-component (CV death or MI) secondary composite outcomes in stable CAD patients with moderate-severe ischaemic burden. In addition, while the extent and severity of anatomic CAD did show worse outcomes for patients with 3-vessel CAD versus 1- to 2-vessel CAD, there was no benefit in terms of CV death or MI with revascularisation.

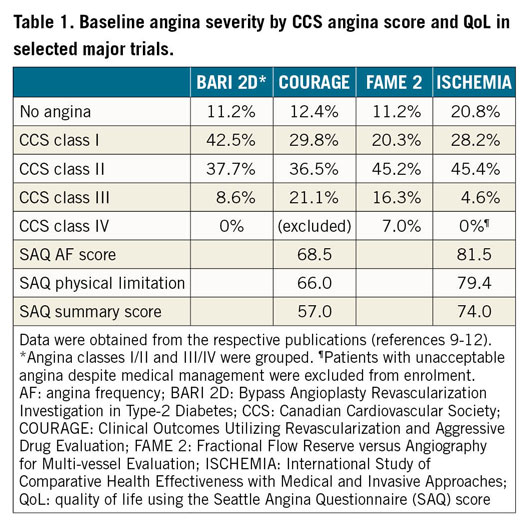

However, in order to understand how (or if) the results of ISCHEMIA can be applied more broadly to clinical decision making in unselected patients with stable CAD, it is essential to clarify the degree to which the ISCHEMIA trial study population is the same as or different from RWE/RWD derived from observational cohort studies like START. It is important to emphasise that ISCHEMIA, by design, excluded patients <18 years of age, those with recent (<2 months) acute coronary syndrome, unprotected left main stenosis ≥50%, left ventricular ejection fraction ≤35%, Class III or IV heart failure, and unacceptable angina despite medical therapy9. Another important observation is that, despite the extent and severity of baseline ischaemia, only 21% of ISCHEMIA patients had daily or weekly angina, while 44% had 1-3 anginal episodes per month, and 35% were asymptomatic at randomisation. This discordance between the burden of baseline ischaemia and angina suggests that the ISCHEMIA population was a somewhat anomalous group compared with earlier RCTs, as depicted in Table 1, and with what is generally observed in contemporary practice among more symptomatic stable CAD patients who are generally treated with revascularisation. In fact, compared with baseline characteristics of patients in ISCHEMIA15, the “ISCHEMIA-Like” population in START14 was older (median age 67 vs 64 years) and had a higher incidence of prior MI (53% vs 19%) and prior revascularisation (61% vs 25%), though there was less diabetes (29% vs 42%) and 3-vessel CAD (12% vs 40%).

While routine non-invasive ischaemia testing with perfusion imaging or stress echocardiography was not a requirement for enrolment in START, this probably explains why the proportion of “ISCHEMIA-Excluded/Unclassifiable” patients was so high, which is an important limitation that the authors acknowledge. Accordingly, the “ISCHEMIA-Like” patients included in START might have been at lower risk than those enrolled in ISCHEMIA. Nevertheless, De Luca et al did perform 1:1 propensity matching using all baseline covariates without missing data, and which did define 193 matched patients in each group with identical very low rates for the primary composite outcome (1 of 193 patients [0.5%] in each group, p=1.0), though this propensity analysis represented only 7.6% of all START participants.

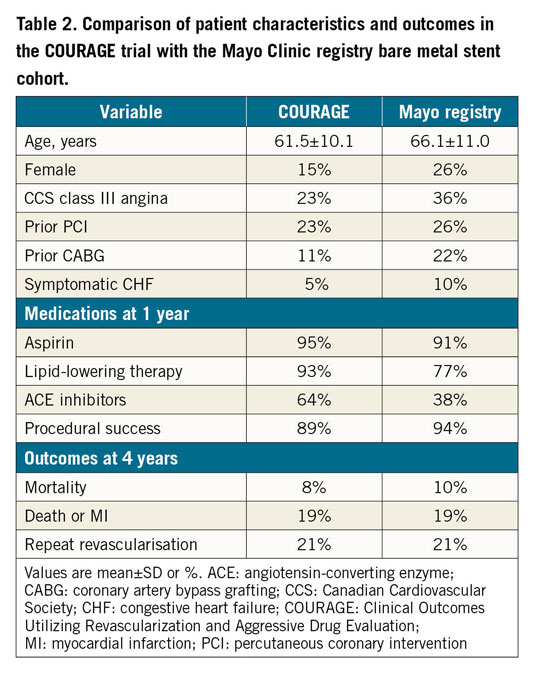

In terms of evaluating the applicability of the ISCHEMIA results to the national Italian registry in stable CAD patients, its external applicability seems, at best, poor. By contrast, when a similar comparative assessment of the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive druG (COURAGE) trial10 findings was performed with observational data derived from the Mayo Clinic’s large clinical data repository in 201016, it was observed that both clinical characteristics and, importantly, four-year outcomes were very well matched, with identical rates of death or MI (19%) and subsequent revascularisation (21%), respectively (Table 2).

What is the “take-home” message for the academic and clinical practice cardiology communities from the present study? The observations from START inevitably raise three important questions in terms of how we should view and reconcile these RWD/RWE data and the RCT findings of ISCHEMIA. 1) How similar or different are the ISCHEMIA trial patients to the larger universe of unselected stable CAD patients who are encountered in the routine practice setting? 2) To what degree are the results of the ISCHEMIA trial actionable in terms of providing clarity of clinical decision making? 3) Is it likely that ISCHEMIA will change clinical practice and subsequent management guidelines?

Certainly, based on START, it appears that the external generalisability of the ISCHEMIA trial findings to routine clinical practice of stable CAD patients is quite limited. ISCHEMIA as well as earlier trials9,10,11,12,13,14 show no CV event reduction with revascularisation compared with OMT alone. We have likewise known for decades that revascularisation is better than OMT alone for angina relief and QoL improvement, particularly among those patients with more severe symptoms, yet only about 1 in 5 ISCHEMIA participants had daily/weekly angina. Thus, barring unacceptable angina despite OMT, the great majority of stable CAD patients should be treated intensively medically, and this approach needs to be prioritised. ISCHEMIA also tells us that even selected patients deemed high-risk due to extensive ischaemic burden do not benefit from revascularisation, refuting observational data that have endorsed such treatment decisions and guidelines for over two decades. Also, because ISCHEMIA excluded patients with unacceptable angina, advanced heart failure, ejection fraction ≤35%, and unprotected left main CAD, our management might be more appropriately redirected towards identifying such patients for consideration of revascularisation in addition to an initial strategy of OMT. Whether this diagnostic approach embodies an anatomic assessment and/or a functional assessment of residual risk remains unsettled.

Lastly, we must be reminded that the START findings, though provocative and perhaps disappointing, are literally just that – they are simply a “start” to a process that demands further prospective study to assess more carefully and reliably the validity and external generalisability of the ISCHEMIA trial results. Until we have more robust RWE/RWD data with which to compare clinical outcomes in stable CAD patients such as those enrolled in ISCHEMIA, we should acknowledge that application of the ISCHEMIA results to routine clinical practice remains challenging at best.

Conflict of interest statement

W.E. Boden discloses the following relationships – research grant support from Clinical Trials Network, Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology, Research, and Information Center (MAVERIC), VA New England Healthcare System; NHLBI as National co-Principal Investigator for the ISCHEMIA Trial; American College of Cardiology: ACCEL Board Member; Axio Research, Inc., Seattle, WA; AbbVie; Amarin Pharmaceuticals. Inc.; Amgen; AstraZeneca; Sanofi Aventis. Board of Directors, Boston VA Research Institute, Inc.; Data Monitoring Committee for VA Cooperative Studies Program; National Coordinator, STRENGTH Trial, with honoraria from the Cleveland Clinic Clinical Coordinating Center. Speaking honoraria and fees from Amgen; AstraZeneca; Janssen Pharmaceutical; Regeneron. D.L. Bhatt discloses the following relationships – Advisory Board: Cardax, CellProthera, Cereno Scientific, Elsevier Practice Update Cardiology, Level Ex, Medscape Cardiology, MyoKardia, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Regado Biosciences; Board of Directors: Boston VA Research Institute, Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care, TobeSoft; Chair: American Heart Association Quality Oversight Committee; Data Monitoring Committees: Baim Institute for Clinical Research (formerly Harvard Clinical Research Institute, for the PORTICO trial, funded by St. Jude Medical, now Abbott), Cleveland Clinic (including for the ExCEED trial, funded by Edwards), Contego Medical (Chair, PERFORMANCE 2), Duke Clinical Research Institute, Mayo Clinic, Mount Sinai School of Medicine (for the ENVISAGE trial, funded by Daiichi Sankyo), Population Health Research Institute; Honoraria: American College of Cardiology (Senior Associate Editor, Clinical Trials and News, ACC.org; Vice-Chair, ACC Accreditation Committee), Baim Institute for Clinical Research (formerly Harvard Clinical Research Institute; RE-DUAL PCI clinical trial steering committee funded by Boehringer Ingelheim; AEGIS-II executive committee funded by CSL Behring), Belvoir Publications (Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter), Canadian Medical and Surgical Knowledge Translation Research Group (clinical trial steering committees), Duke Clinical Research Institute (clinical trial steering committees, including for the PRONOUNCE trial, funded by Ferring Pharmaceuticals), HMP Global (Editor in Chief, Journal of Invasive Cardiology), Journal of the American College of Cardiology (Guest Editor; Associate Editor), K2P (Co-Chair, interdisciplinary curriculum), Level Ex, Medtelligence/ReachMD (CME steering committees), MJH Life Sciences, Population Health Research Institute (for the COMPASS operations committee, publications committee, steering committee, and USA national co-leader, funded by Bayer), Slack Publications (Chief Medical Editor, Cardiology Today’s Intervention), Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care (Secretary/Treasurer), WebMD (CME steering committees); Other: Clinical Cardiology (Deputy Editor), NCDR-ACTION Registry Steering Committee (Chair), VA CART Research and Publications Committee (Chair); Research Funding: Abbott, Afimmune, Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cardax, Chiesi, CSL Behring, Eisai, Ethicon, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Forest Laboratories, Fractyl, Idorsia, Ironwood, Ischemix, Lexicon, Lilly, Medtronic, MyoKardia, Pfizer, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi, Synaptic, The Medicines Company; Royalties: Elsevier (Editor, Cardiovascular Intervention: A Companion to Braunwald’s Heart Disease); Site Co-Investigator: Biotronik, Boston Scientific, CSI, St. Jude Medical (now Abbott), Svelte; Trustee: American College of Cardiology; Unfunded Research: FlowCo, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Takeda.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.