Abstract

Aims: A large trial established the favourable clinical profile of a new polymer-free biolimus A9-eluting stent (PF-BES) with a one-month dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) regimen in patients at high bleeding risk (HBR). We aimed to evaluate the real-world patterns of indications, DAPT strategies and outcomes for the PF-BES following this evidence.

Methods and results: CHANCE is a multicentre registry including all patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with at least one PF-BES. The reasons for the PF-BES PCI and planned antithrombotic regimens were collected. Primary outcomes were the 390-day Kaplan-Meier estimates of patient-oriented and device-oriented composite endpoints (POCE: death, myocardial infarction [MI] or target vessel revascularisation [TVR]; DOCE: cardiac death, target vessel MI or ischaemia-driven target lesion revascularisation [ID-TLR]). Between January 2016 and July 2018, 858 patients (age 74±10 years, 64.6% male, 58.7% acute coronary syndrome presentation) underwent PF-BES PCI. The main reasons for the physicians’ choice of PF-BES reflected a perceived HBR in 77.7% of patients. One-month DAPT was planned in 40.3% of patients. At 390-day follow-up (median 340 days, interquartile range: 187-390 days), the estimated incidence of POCE was 13.1% (any MI 3.7%, any TVR 3.4%) and of DOCE was 7.1% (TV-MI 3.6%, ID-TLR 1.4%), while the 390-day estimate of any bleeding event was 11.1% (BARC 3-5 bleeding 3.0%).

Conclusions: In a large all-comers registry, PF-BES was used mostly in HBR patients, frequently followed by a very short DAPT regimen. The reported outcomes suggest a favourable safety and efficacy profile for the PF-BES in a real-world clinical setting. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03622203

Introduction

Successfully developed to overcome the high rates of bare metal stent (BMS) restenosis, the drug-eluting stent (DES) initially had the downside of increased late stent thrombosis (ST) and in-stent neoatherosclerosis, even in high-risk settings1,2. These phenomena, related to negative clinical outcomes, may be caused partly by the persistence of the polymer coating, which may trigger chronic inflammation, compromising arterial healing in the treated coronary segment3,4.

The BioFreedom™ stent (Biosensors Interventional Technologies, Singapore) is a stainless steel polymer-free biolimus-eluting stent (PF-BES) with a strut thickness of 112 μm. The bare metal platform of this stent presents a selectively micro-structured, abluminal surface harbouring biolimus, a highly lipophilic sirolimus analogue absorbed by the vessel wall within a period of one month5. The absence of a polymer coating along with the fast drug elution seems to prevent the delayed or incomplete healing and the resulting risk of late ST observed with polymer-coated DESs1,6,7.

While the safety of early dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) cessation with polymer-coated DESs is still a matter of debate8, the large-scale LEADERS FREE trial established the favourable clinical profile of the PF-BES when used with a one-month DAPT strategy in high bleeding risk (HBR) patients9. This evidence, along with current guidance recommending BMS avoidance across any clinical scenario10, might have favoured the operator choice for PF-BES in HBR patients, a constantly growing subset of patients requiring percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)9. However, most of the HBR features such as diabetes or renal failure increase in parallel with the incidence of restenosis and of ST, stressing the need for data from a real-world scenario - currently limited to a single all-comers registry, enrolling most patients before the publication of the LEADERS FREE trial11. Thus, no data exist on the contemporary indications and outcomes for the PF-BES following demonstration of the safety of a one-month DAPT strategy with this stent. The aim of this study was to evaluate contemporary real-world patterns of use, DAPT strategies and associated outcomes for the PF-BES in patients undergoing PCI.

Methods

STUDY DESIGN

The CHANCE registry (Outcome of CHAllenging lesioNs and Patients Treated With Polymer Free Drug-CoatEd Stent; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03622203) is an Italian multicentre observational prospective all-comers registry including all patients who underwent PCI with at least one PF-BES implantation across 10 Italian sites, following publication of the LEADERS FREE trial results (from January 2016 to July 2018). All consecutive patients undergoing PCI with attempted placement of at least one PF-BES as part of routine clinical care were enrolled in the registry.

The PCI procedure was performed as per standard of care at each site. DAPT selection and duration were at the discretion of the treating physician and according to local policy.

ENDPOINTS AND DEFINITIONS

Primary outcomes were the cumulative incidence at 390 days of the patient-oriented composite endpoint (POCE: a composite of death, any myocardial infarction or any target vessel revascularisation [TVR]) and of the device-oriented composite endpoint (DOCE: a composite of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction [TV-MI], and ischaemia-driven target lesion revascularisation [ID-TLR]). Other outcomes included the 390-day cumulative incidence of ST, any bleeding (defined according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium [BARC] definition), BARC 3-5 bleedings, and the individual composite endpoint components. Endpoint definitions, patient consent and statistical methods are detailed in Supplementary Appendix 1.

Results

STUDY POPULATION

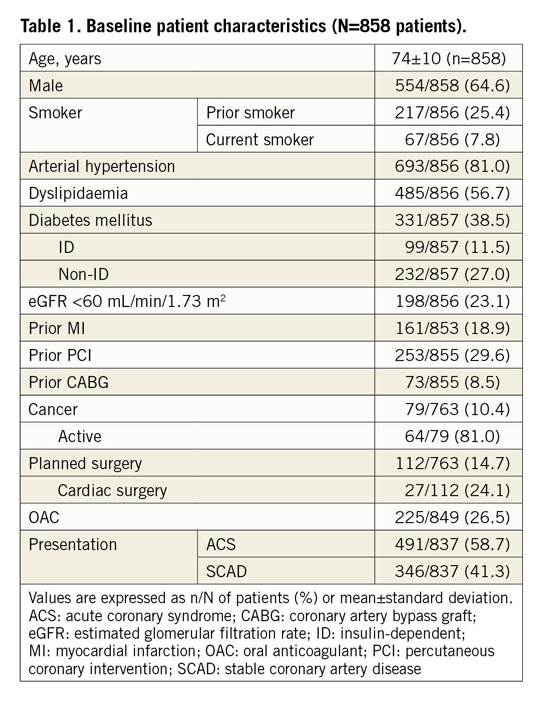

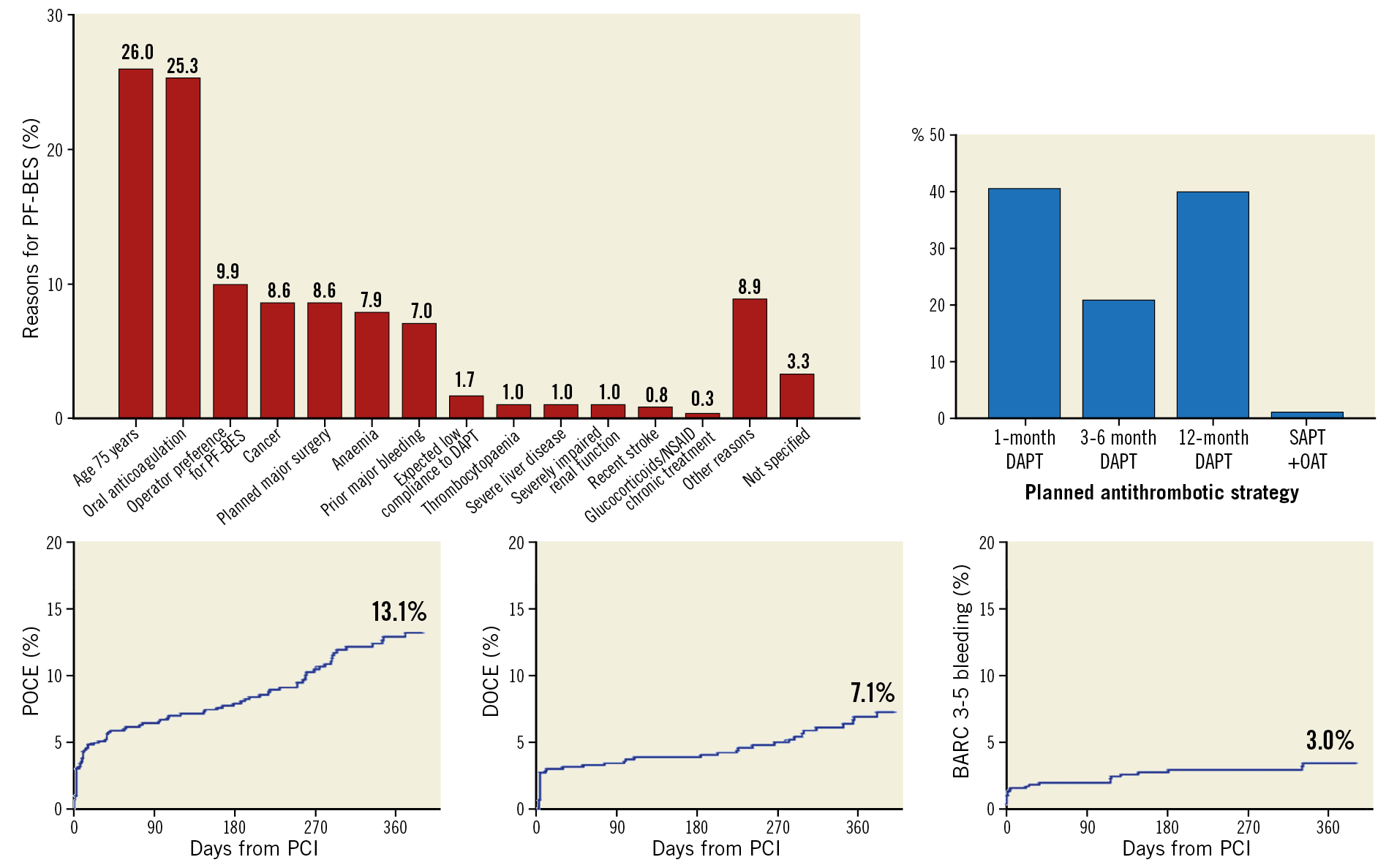

Between January 2016 and April 2018, 858 patients were enrolled across 10 Italian sites. Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1 present the baseline characteristics of the included patients. Mean age was 74±10 years, 64.6% of patients were male. At admission, 26.5% of patients were on oral anticoagulant (OAC) therapy, 10.4% had a cancer (81.4% active) and 14.7% had a planned surgery (24.1% cardiac); 58.7% of patients presented with an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and 41.3% with stable coronary artery disease (SCAD).

Reasons for PF-BES implantation as reported by the treating physician are presented in Figure 1. The main reasons (not mutually exclusive) were advanced age (>75 years, 26.0%), OAC planned to continue after PCI (25.3%), operator preference for PF-BES (9.9%), planned major surgery (8.6%), cancer (8.6%), anaemia (7.9%), recent bleeding (7.0%), expected low DAPT compliance (1.7%), thrombocytopaenia (1.0%), severe liver disease (1.0%), severely impaired renal function (1.0%), recent stroke (0.8%) and glucocorticoid or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug chronic treatment (0.3%). Overall, the operator choice to implant a PF-BES reflected a perceived HBR or need for a short DAPT regimen in 77.7% of the population, as defined by the presence of at least one inclusion criterion of the LEADERS FREE trial9.

Figure 1. Contemporary reasons, dual antiplatelet therapy strategies and clinical outcomes for a polymer-free biolimus A9-coated stent. In the real-world setting, reasons for PF-BES implantation reflected in most cases the operator-perceived high bleeding risk of the patient (top left). Following PF-BES PCI, a very short DAPT strategy was frequently implemented (top right). Despite the baseline high-risk features, the observed cardiovascular outcomes suggest a favourable safety and efficacy profile for the PF-BES in this all-comer real-world population (bottom). Reported reasons are not mutually exclusive.

PROCEDURAL CHARACTERISTICS AND OUTCOMES

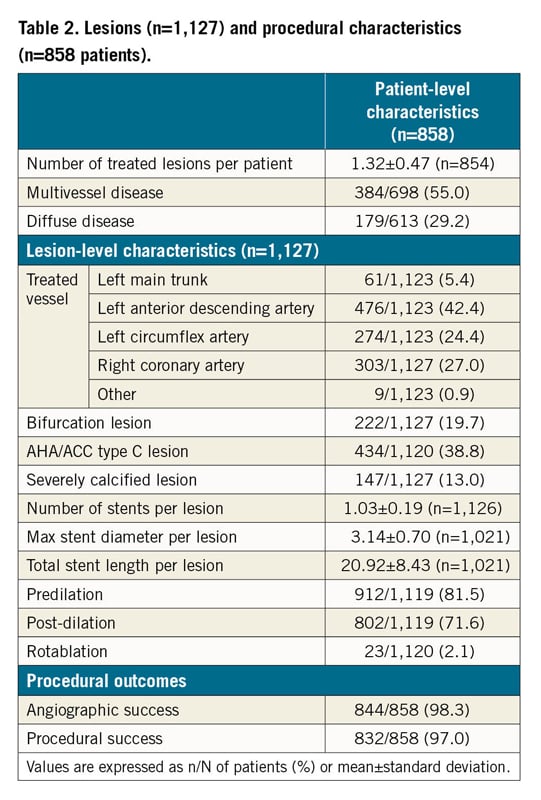

Lesion and procedural characteristics are shown in Table 2. Overall, 55.0% of patients had multivessel disease, with 29.2% having diffuse disease. A total of 1,127 lesions (mean 1.32±0.47 lesions per patient) were treated with PF-BES (mean 1.03±0.19 stents per lesion). Lesions were homogeneously distributed among the epicardial vessels, with the majority being located in the left anterior descending artery (42.4%). Total stent length per lesion was 20.92±8.43 mm, with maximum stent diameter per lesion being 3.14±0.70 mm. Among the lesions, 38.8% displayed American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) type C features, 13.0% were severely calcified, and 19.7% were bifurcation lesions. Predilation and post-dilation were performed in 81.5% and 71.6% of all lesions, respectively.

Angiographic success was achieved in 98.3% and procedural success in 97.0% of patients.

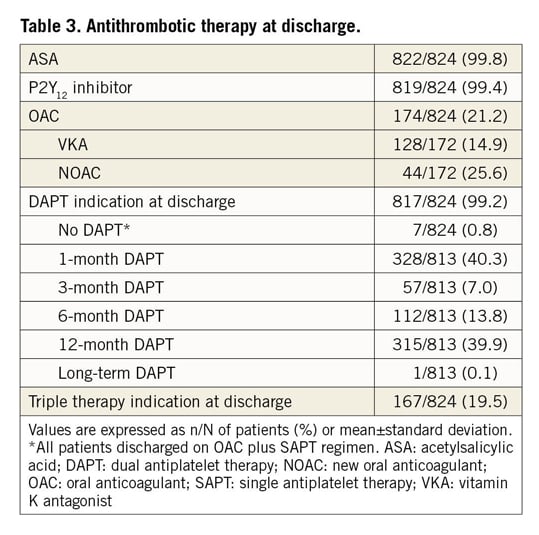

Antithrombotic therapy at discharge is shown in Table 3 and Supplementary Table 2. Aspirin and P2Y12 inhibitors were prescribed at discharge in 99.8% and 99.4% of patients, respectively. Overall, 99.2% of patients were discharged on DAPT, 19.5% on triple therapy, and 0.8% on single antiplatelet therapy plus OAC. Planned DAPT duration at discharge was one month in 40.3% of patients, with 33.8% of these being on triple therapy. Among patients on triple therapy, 66.5% had a planned duration of one month.

CLINICAL OUTCOMES

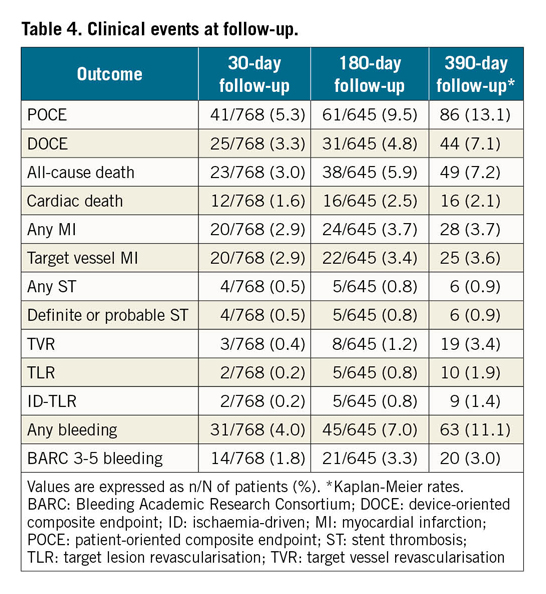

Clinical outcomes are shown in Table 4. Out-of-hospital follow-up was available for 799 (93.1%) patients.

Kaplan-Meier estimates at 390 days (median follow-up 340 days, interquartile range: 187-390 days) for the occurrence of the primary endpoints were as follows: POCE 13.1% (any MI 3.7%, any TVR 3.4%), DOCE 7.1% (TV-MI 3.6%, ID-TLR 1.4%), while the 390-day any ST estimate was 0.9%. The 390-day estimate of the any bleeding outcome was 11.1% (BARC 3-5 bleeding 3.0%).

Supplementary Table 3-Supplementary Table 5 provide univariate and multivariate analysis for predictors of the primary outcomes. At multivariate analysis, independent predictors of 390-day POCE were eGFR ≤60 ml/min (HR 1.81, 95% CI: 1.09-3.04, p=0.028), a history of cancer (HR 2.62, 95% CI: 1.43-4.81, p=0.002) and severely calcified lesions (HR 2.05, 95% CI: 1.09-3.85, p=0.025). Independent predictors of 390-day DOCE were a previous MI (HR 2.06, 95% CI: 1.03-4.15, p=0.041), a history of cancer (HR 2.69, 95% CI: 1.18-6.13, p=0.019) and bifurcation lesions (HR 2.66, 95% CI: 1.38-5.13, p=0.004).

CLINICAL OUTCOMES ACCORDING TO CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Baseline clinical, lesion and procedural characteristics of patients undergoing PF-BES PCI following an ACS (n=491, 58.7%) as compared to those of patients with a stable presentation (n=346, 41.3%) are detailed in Supplementary Table 5 and Supplementary Table 6.

In patients with ACS as compared to SCAD presentation, a potent P2Y12 inhibitor (20.6% vs 16.0%, p<0.001) and a longer DAPT duration (12 months [IQR 1-12 months] vs 1 month [IQR 1-6 months], p<0.001) were most frequently prescribed (Supplementary Table 7).

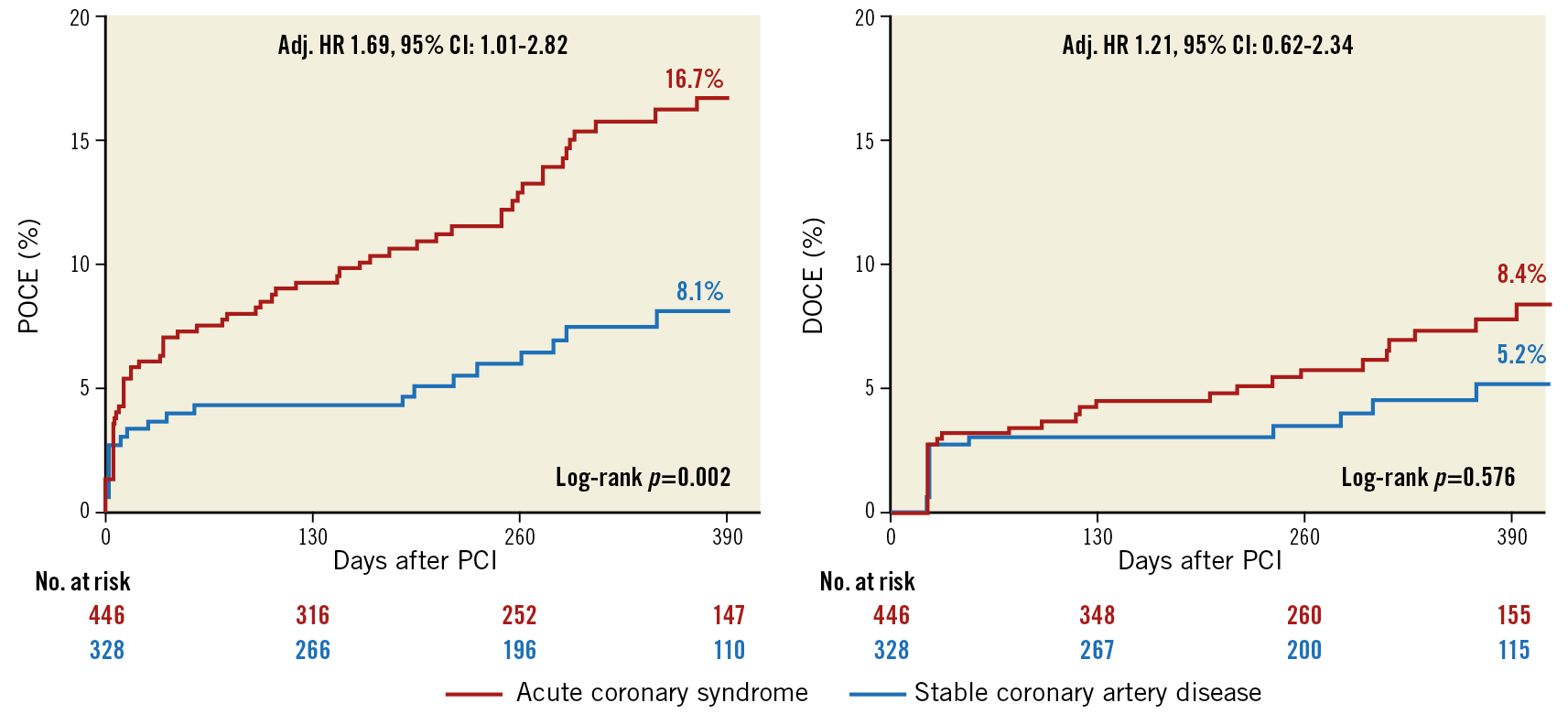

Clinical outcomes stratified by clinical presentation are reported in Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 8. Patients presenting with an ACS had a higher 390-day estimated incidence of the POCE, also after adjustment for confounding variables (ACS vs SCAD: 16.7% vs 8.1%, log-rank p=0.002; adj. HR 1.69 [1.01-2.82]), while no difference in the 390-day estimated incidence of DOCE was observed (ACS vs SCAD: 8.4% vs 5.2%; p=0.168, adj. HR 1.21 [0.62-2.34]). The estimates of any ST at 390 days for ACS vs SCAD patients were 1.3% and 0.3% (p=0.193).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier estimates of primary endpoints at 390-day follow-up stratified by clinical presentation.

Discussion

The LEADERS FREE trial established the better clinical profile of a DES, the PF-BES, over a BMS in patients at high bleeding risk when combined with a very short (one-month) DAPT regimen. CHANCE is the first registry providing insights into real-world patterns of indications, DAPT strategies and outcomes for the PF-BES, following publication of the LEADERS-FREE trial. The main findings of this study can be summarised as follows (Figure 1).

1) In a large, contemporary all-comers registry, the main reasons for PF-BES use in most cases reflected the operator-perceived HBR of the patient.

2) The real-life population for which PF-BES implantation was selected shows a high overall prognostic risk as established by the observed elevated all-cause death rate.

3) Following PF-BES PCI, a very short DAPT strategy was frequently implemented.

4) Despite the high-risk features of the study population, the cardiovascular outcomes observed in CHANCE suggest a favourable safety and efficacy profile for the PF-BES in a real-world setting.

For an overview of PF-BES development rationale, technological characteristics, preclinical and surrogate clinical outcomes, please see Supplementary Appendix 2.

The favourable clinical profile of the PF-BES in a wide real-world population was assessed for the first time in the RUDI-FREE registry. In this study, comprising mainly patients with non-HBR features (83.7%), the PF-BES was associated with a high one-year safety and efficacy performance, with outcomes in the lower range of cardiovascular adverse event rates observed with contemporary new-generation DESs12.

Concurrently, the LEADERS FREE trial, comparing PF-BES with BMS in HBR patients followed by one-month DAPT, demonstrated superior safety and efficacy in this setting with this new technology9. No such evidence currently exists for any other commercially available DESs, hampering evidence-based recommendation on a one-month DAPT strategy in HBR patients undergoing non-PF-BES DES PCI. This recognition may have favoured the implementation of PF-BES across real-world cath labs with a specific indication for patients with adherence restraints, such as HBR patients.

Of note, a prospective randomised comparison of the BioFreedom PF-BES with the Resolute Onyx™ zotarolimus-eluting stent (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) followed by one-month DAPT in HBR patients (Onyx ONE trial, NCT03344653) and a comparison of different DAPT durations (1-month vs >1-month) following Ultimaster® biodegradable polymer sirolimus-eluting stent (Terumo Corp., Tokyo, Japan) implantation in HBR patients (MASTER DAPT trial, NCT03023020) are currently ongoing and will provide insights on the potential use of other stent platforms in this setting.

In CHANCE, the first all-comers registry evaluating real-world use of PF-BES following LEADERS FREE, we found that roughly three out of four patients were implanted with PF-BES due to the operator-perceived high bleeding risk, which was the driver of the operator preference for PF-BES. This proportion is markedly different from the 16.3% of patients displaying HBR features (as defined by a CRUSADE score >40) of the RUDI-FREE registry, where most of the enrolment period was prior to LEADERS FREE publication. Even if the reasons driving the operator choice for PF-BES were not reported in the RUDI-FREE study and despite the different criteria used to define the bleeding risk status, this observation may suggest a changing pattern of indications for PF-BES in real practice, reflecting the evidence base for the use of this sole stent with a very short DAPT strategy. This is further substantiated by the striking increase in the one-month planned DAPT rates as compared to RUDI-FREE (40.3% vs 4.9% of patients).

Beyond high bleeding risk, the baseline features observed in CHANCE reflect an overall high prognostic risk: 56.5% of patients were older than 75 years, 23.1% had at least stage 3a chronic kidney disease, 10.4% had a cancer (81.4% active) and 14.7% had a planned surgery (24.1% cardiac). This is likely to have translated into the 7.2% estimated 390-day all-cause mortality (5.1% non-cardiovascular death) as well as the 3.0% estimated 390-day BARC 3-5 bleedings found in the study. This is consistent with data from the three available randomised controlled trials evaluating DESs in patients with HBR features9,13,14, showing only slightly higher all-cause mortality and BARC bleeding rates than CHANCE (Supplementary Table 9, columns one to three).

As high bleeding predictors largely overlap with risk factors for ischaemic complications, high bleeding risk per se is an overall marker of the ischaemic risk13,15. This recognition, together with the observed anatomical presentation (29.2% diffuse disease, 19.7% bifurcation lesions, 38.8% type C lesions), establishes the concurrent high ischaemic risk of the CHANCE population. Notwithstanding this, we found acceptable rates of 390-day cardiovascular outcomes, reflecting the good clinical profile of the PF-BES in a contemporary real-world setting. For comparison, the safety outcomes of cardiac death, ST and MI were only slightly increased above the superior IQR reference limit of adverse event rates in a randomised controlled trial of well-selected non-HBR patients undergoing contemporary DES PCI reported by the ESC/EAPCI Task Force for coronary stent evaluation12 (Supplementary Table 9, far right column). Conversely, the efficacy endpoint of TLR was well below the median reference value of the same analysis, possibly reflecting the optimal antirestenotic profile of biolimus, which remains in the coronary tissues until 180 days after stent implantation, with less than 1% of the original amount on the PF-BES following the first four weeks5.

As expected, CHANCE event rates appear higher than those observed in the RUDI-FREE registry, in line with the different baseline features of the two populations. Importantly, despite the higher rates of the outcomes reflecting the overall patient-level risk, those more closely reflecting device-level performance (i.e., ST and TLR) were similar between studies (Supplementary Table 9). This finding, suggesting a favourable PF-BES performance irrespective of the patient baseline characteristics, supports the feasibility of this stent across a wide range of real-life patients. Comparative evidence with new-generation DESs is needed to support this observation.

Limitations

The findings of this observational study should be interpreted in the context of some limitations. First, we abstracted clinical variables on the basis of documentation in medical records; the completeness of that documentation may not have been consistent either across hospitals or over time. Second, the study was not powered to evaluate rare events such as TLR and ST. With this premise, the low TLR and ST incidences observed in our study are nevertheless reassuring regarding the favourable profile of PF-BES in this setting. Third, the observational nature of this study, with the absence of a control arm, does not allow providing direct comparative evidence of the PF-BES performance in respect to other new-generation DESs. Notwithstanding this, indirect comparison of the PF-BES outcomes of both our high-risk and a more benign population11 with new-generation DESs in either HBR or non-HBR settings (Supplementary Table 9) suggests that the performance of PF-BES is comparable with new-generation DESs across a wide range of real-world patients.

Conclusions

In this large, contemporary all-comers registry, PF-BES use was frequently adopted in HBR patients, often followed by a very short DAPT strategy. The observed outcomes, in the context of previously available data, suggest a favourable safety and efficacy profile for the PF-BES across a wide range of real-world patients.

|

Impact on daily practice A new polymer-free biolimus A9-eluting stent (PF-BES) showed a favourable clinical profile in a large clinical trial, when used with a one-month DAPT regimen in HBR patients. Our results show that the PF-BES is associated with a favourable clinical profile across a wide range of real-world patients when a one-month DAPT duration is deemed necessary by the treating physician. |

Appendix. Study collaborators

Mauro Rinaldi, MD; Città della Salute e della Scienza, Turin, Italy. Fabrizio Ugo, MD; Ospedale San Giovanni Bosco, Turin, Italy. Andrea Montabone, MD; Ospedale San Giovanni Bosco, Turin, Italy. Roberto Adriano Latini, MD; Ospedale Fatebenefratelli, ASST Fatebenefratelli/Sacco, Milan, Italy. Maurizio D’Urbano, MD; Ospedale di Magenta, ASST Milanese Ovest, Milan, Italy. Gaetano Senatore, MD; Ospedale Civile, Ciriè, Turin, Italy. Erika Ferrara, MD, Ospedale di Legnano, ASST Milanese Ovest, Milan, Italy. Enrico Cerrato, MD; Infermi Hospital, Rivoli, Turin, Italy. Mauro Pennone, MD; Department of Internal Medicine, Città della Salute e della Scienza, Turin, Italy. Pierluigi Omedè, MD; Department of Internal Medicine, Città della Salute e della Scienza, Turin, Italy. Antonio Montefusco, MD; Department of Internal Medicine, Città della Salute e della Scienza, Turin, Italy. Maurizio D’Amico, MD; Department of Internal Medicine, Città della Salute e della Scienza, Turin, Italy.

Guest Editor

This paper was guest edited by Alec Vahanian, MD, PhD; Department of Cardiology, Hôpital Bichat-Claude Bernard, and University Paris VII, Paris, France.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors and the collaborators have no conflicts of interest to declare. The Guest Editor is a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences.