Abstract

Aims: The successful use of everolimus on a durable polymer was earlier reported with 6 and 12 months data from this first-in-man study. This reports the long-term follow-up of the XIENCE V everolimus-eluting stent.

Methods and results: This prospective, single-blinded, randomised, multicentre clinical trial evaluated the safety and efficacy of the XIENCE V everolimus-eluting coronary stent system versus an identical bare metal stent in the treatment of patients with a single de novo coronary artery stenosis of ≥50% and <100% and a vessel diameter of 3.0 mm as assessed by on-line quantitative coronary angiography that could be covered by a single 18 mm stent.

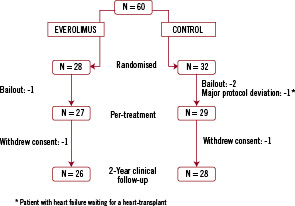

Sixty patients were randomised and at two-year follow-up, clinical data was available in 96% and 97% of patients in the everolimus and control arm, respectively. Four patients were excluded due to protocol violations and two patients withdrew consent.

In the everolimus arm no additional death, myocardial infarction, clinically driven TLR, or TVR events were observed between one and two-year follow-up. The 2-year hierarchical MACE rate for the everolimus arm remained 15.4% (4/26). In the control group, two patients had a clinically driven target lesion revascularisation. MACE rate increased from 21.4% (6/28) to 25.0% (7/28) in the control group.

Conclusions: This report confirms and extends the safety and efficacy results of the durable polymer XIENCE V everolimus-eluting stent up to two years as compared to identical bare metal stents.

Introduction

Large randomised studies have shown the superiority of drug-eluting stents (DES) over bare metal stents in clinical and angiographic outcomes after percutaneous treatment of coronary artery stenosis.1-9 Thus far, long-term follow-up data is limited and only available for sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stents.10-13

The SPIRIT FIRST clinical trial represents the first clinical evaluation of the XIENCE V everolimus-eluting coronary stent system, to study the safety and efficacy compared to identical bare metal stents. Six months angiographic and intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) follow-up showed significantly less neointimal hyperplasia in the everolimus-eluting stent.14 At one year, these angiographic and IVUS results were maintained. Furthermore, the clinically driven percutaneous revascularisation rate was reduced by more than 50% for patients treated with an everolimus-eluting stent.15 This report extends the clinical results of the durable polymer everolimus-eluting stent up to two years.

Methods

Study population

The study design of the SPIRIT FIRST clinical trial has been reported previously.14,15 In brief, the design was a prospective, controlled, randomised, single-blinded, parallel 2-arm, multicentre clinical trial. Patients enrolled in the study had a single de novo coronary artery stenosis of ≥50% and <100% and a vessel diameter of 3.0 mm as assessed by on-line quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) that could be covered by a single 18 mm stent. Major exclusion criteria included an evolving myocardial infarction, a stenosis of an unprotected left main coronary artery, an ostial location, a location within 2 mm of a bifurcation, a lesion with moderate to heavy calcification, an angiographically visible thrombus within the target vessel, a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 30%, patients awaiting a heart transplant, or patients suffering a contraindication to aspirin, clopidogrel, heparin, or any drugs related to this study.

The study was approved by each participating institution’s Ethical Review Committee, and all patients gave written informed consent prior to randomisation.

Study procedure

Prior to the procedure, patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio in a single-blinded manner to either a XIENCE V everolimus-eluting stent or a MULTI-LINK VISION stent (both produced by Abbott Cardiovascular Systems, an Abbott Vascular Company, CA, USA). Target lesions were treated according to standard interventional techniques with mandatory pre-dilatation. Post-dilatation was at the discretion of the operator. Clinical success was defined as a successful implantation of the assigned study device, residual in-stent stenosis of <50%, and freedom from in-hospital major cardiac events.

Aspirin was started at least 24 hours prior to procedure and continued indefinitely at a minimum dose of 80 mg per day. All patients received a loading dose of 300 mg of clopidogrel prior to the procedure (unless the patient was already receiving clopidogrel, then the loading dose could be adjusted or omitted) followed by 75 mg daily for a minimum of three months.

The everolimus-eluting stent

The XIENCE V Everolimus Eluting Stent is comprised of the MULTI-LINK VISION™ cobalt chromium (CoCr) stent (Abbott Cardiovascular Systems, an Abbott Vascular Company, CA, USA) and a polymer coating consisting of two layers; a primer layer and a drug reservoir layer. This polymer coating contains two polymers; an acrylic polymer and a fluoro polymer, both approved for use in blood contacting applications. The everolimus-polymer matrix layer is loaded with 100 µg/cm2 of everolimus on the stent surface area with no top coat polymer layer. Approximately 75% of the drug is released within 30 days after implantation.

Everolimus is a powerful anti-proliferative agent16 that inhibits the growth factor-stimulated phosphorylation of p70 S6 kinase and 4E-BP1. The latter proteins are key proteins involved in the initiation of protein synthesis. Since phosphorylation of these proteins is under control of FRAP (FKBP-12-rapamycin associated protein) these findings suggest that the everolimus-FKBP12 complex binds to and thus interferes with the function of FRAP. FRAP is a key regulatory protein which governs cell metabolism, growth, and proliferation. Disabling FRAP function explains the cell cycle arrest at the late G1 stage caused by everolimus. Everolimus has shown to be effective in conjunction with other medications to prevent heart and renal transplant rejection.17,18

Follow-up

Clinical evaluation was scheduled at one, six, 12 and 24 months with annual evaluation up to five years. Follow-up was obtained by office visit or a telephone interview and included a series of questions for the determination of the occurrence of death, recurrent angina, repeat angiography, functional testing performed, myocardial infarction, repeat revascularisation procedure, and any other hospitalisation. In case a major adverse cardiac event was reported, review of hospital records, chart review, telephone contact with the referring cardiologists or the patient’s general practitioner were used to complete information.

Study endpoints and definitions

The primary endpoint was in-stent late loss at 180 days. The major secondary endpoint was percent in-stent volume obstruction (%VO) at 180 days based on IVUS analysis.

The 2-year clinical follow-up results focus on the following: a) major adverse cardiac events (MACE) comprised of cardiac death, Q-wave or non-Q-wave myocardial infarction, or clinically driven surgical or percutaneous target lesion revascularisation; b) target vessel failure (TVF) comprised of MACE and clinically driven target vessel revascularisation (TVR). All deaths that could not be clearly attributed to another cause were considered cardiac deaths. A non-Q-wave myocardial infarction was defined as an increase in the creatine kinase (CK) level to greater than or equal to twice the upper limit of the normal range, with elevated CK-MB, in the absence of new pathological Q waves on electrocardiography. Clinically driven TVR was defined as a revascularisation of the target vessel associated with a positive functional ischaemia test related to the treated target vessel territory or ischaemic symptoms. Stent thrombosis was defined as a total coronary artery occlusion by angiography at the stent site with abrupt onset of symptoms, elevated biochemical markers and ECG changes consistent with a MI. Stent thrombosis was categorised as acute (< 1 day), subacute (1-30 days) and late (> 30 days).

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint and all other trial endpoints were analysed on the per-treatment evaluable population. The per-treatment evaluable population consisted of patients who had no bailout stenting and no major protocol deviations. The data of all patients were reviewed in a blinded manner to determine whether the patient should be included in this analysis population. Patients were included in the everolimus arm corresponding to the study stent actually received.

The overall sample size calculation for this clinical trial was determined based on the primary endpoint of in-stent late loss at 180 days and on the following assumptions: a single comparison of active to uncoated; one-tailed t-test, unequal and unknown variances in the two groups being compared; α=0.05; true mean late loss difference between the control group and the everolimus group was 0.48 mm. This assumption was made based on the results of the VISION Registry (mean late loss=0.83 mm)19, the SIRIUS trial (mean late loss=0.17 mm)5, and the TAXUS IV trial (mean late loss=0.39 mm)9. Assuming the true mean late loss for the everolimus group was 0.35 mm, the difference between the control group and the everolimus group was calculated as: 0.83-0.35 = 0.48 mm. The standard was assumed to be 0.56 mm in the control group and 0.38 mm in the everolimus group (based on the results of the VISION Registry and the SIRIUS trial); approximately 20% rate of lost to follow-up or drop-out; approximately 10% of patients with bailout stents. Given the above assumptions, enrolling 30 patients per arm (with the analysis of 22 patients per arm) would provide more than 95% power. The trial was not powered to detect any specific differences between the control and the everolimus group for the secondary endpoints. Sample size calculations were performed using NCSS-PASS 2002.

Binary variables were calculated using Clopper-Pearon’s method. Continuous variables, means, standard deviations were calculated using the Gaussian approximation. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS software (version 8.2 or higher; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Between December 2003 and April 2004, a total of 60 study patients (32 control arm; 28 everolimus arm) were randomised and consecutively enrolled at nine European investigational sites. The safety population is composed of these 60 patients. Of these patients, four patients were excluded from the per-treatment population (one due to bailout procedure in the everolimus arm, two due to bailout procedures and one due to a major protocol deviation in the control arm). Hence, the per-treatment population includes 56 patients (27 everolimus arm and 29 control arm).

As previously reported, both arms had similar demographic, angiographic, and procedural characteristics with the exception of a significantly higher number of patients with hypertension requiring treatment in the everolimus arm (70% vs. 41%, p=0.04).14

Major adverse cardiac events

During 2-year follow-up, one patient in each arm withdrew consent. Complete follow-up was available in 96% of patients randomly assigned to the everolimus-eluting stent and 97% of patients randomised to the control group (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Number of patients randomised from the enrolment through 2-year follow-up.

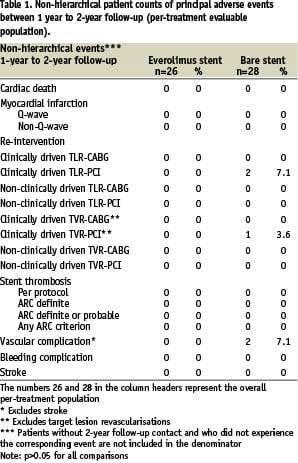

In the everolimus arm, no additional death, myocardial infarction, clinically driven TLR, or TVR events were observed between one and two-year follow-up (Table 1).

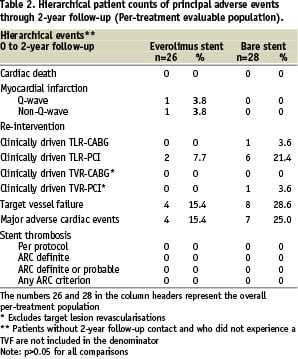

The 2-years hierarchical MACE rate for the everolimus arm remained 15.4% (4/26) (Table 2).

In the control group, one patient developed recurrent angina pectoris and was found to have a proximal edge restenosis of the target lesion. The stenosis was treated by repeat stenting at 755 days after index procedure. A second patient in the control group experienced a clinically driven target lesion revascularisation treated with balloon angioplasty 436 days after the index procedure. One patient in the control group experienced a clinically driven target vessel revascularisation 603 days after index procedure (Table 1). No deaths or myocardial infarctions were reported in the control group. MACE rate increased from 21.4% (6/28) to 25.0% (7/28) in the control group (Table 2). Furthermore, three vascular events were reported in the control arm. One patient had twice a percutaneous transluminal angioplasty of the arteria femoralis superficialis/ arteria poplitea and one patient had a pseudoaneurysm (Table 1). All vascular events were treated successfully.

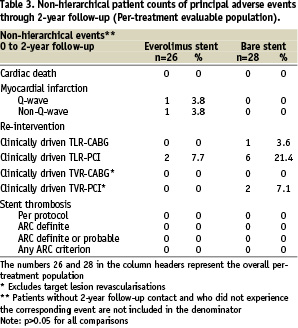

Total non-hierarchical clinically driven TLR (PCI and CABG) rate at two years was 7.7% in the everolimus arm and 25.0% (p=NS) in the control arm (Table 3).

There were no stent thromboses observed in either the everolimus arm or the control arm up to two years according to the per-protocol definition (Table 3). In addition, adjudication of stent thrombosis using the newly published ARC definitions20 did not result in any stent thrombosis in the everolimus arm or the control arm (Table 1-3). There were no angiographic stent thromboses reported and no patients died during 2-year follow-up. Although, in the everolimus group, two patients suffered a myocardial infarction (MI) during 2-year follow-up, both did not contribute to the ARC definitions of stent thrombosis. One patient had a non-target vessel territory Q-wave MI within 6 months after the index procedure, and one patient had a non-Q-wave MI due to a spasm during the 6-months follow-up IVUS procedure. There were no adverse effects reported attributable to the everolimus or the polymer coating of the stent.

Discussion

Two-year clinical follow-up from the randomised SPIRIT FIRST trial demonstrates that the safety and feasibility of the XIENCE V everolimus-eluting stent observed at 1-year follow-up is maintained. No additional TVF events and no very late stent thromboses were reported between one year and two year follow-ups in the everolimus arm.

Currently, long-term clinical results from randomised trials are available for sirolimus-eluting stent (SES) and paclitaxel-eluting stent (PES) in only a small number of patients with relatively non-complex coronary artery lesions. Two-year clinical outcome of SES was obtained in the randomised SIRIUS trial. Between one and two years, the clinical event rate was very low in both groups, (MACE 2.0% vs. 2.9%; TVF 2.3% vs. 1.9%). At two-year follow-up, clinically driven TLR was 5.8% in the SES group vs. 21.3% in the control group, resulting in a significant reduction in MACE (10% vs. 25%), and TVF (12% vs. 27%).13

Two-year clinical follow-up data for PES come from the TAXUS trials. In the TAXUS I trial no additional MACE events were observed between one and two year follow-up. Total MACE at two-year was 3.7% for PES and 11% for the control arm (p=0.63). Furthermore, no stent thromboses were reported up to two years.21 The TAXUS II trial, comparing slow (SR) and moderate release (MR) PES to a BMS, showed one additional TLR in the PES group and eight TLRs in the BMS group from one to two years. MACE rates increased to 14% for both SR- and MR PES vs. 25% BMS (p<0.02) at two-year.22 In the TAXUS IV trial, TLR was 5.6% for PES and 14.4% for the control group at 2-year. Difference in MACE rate retained statistical significance up to two years (14.7% PES vs. 24.9% controls).23

Stent thrombosis was observed in 1.1% for PES and 0.8% in the control group. Noticeably, all stent thromboses occurred within the first year after stent placement in the control group, whereas in the PES group, 0.5% of the stent thromboses occurred between one and two years.23

The long-term results of the SPIRIT FIRST clinical trial show comparable data to SES and PES for the maintenance of safety and efficacy. As reported previously15, one-year angiographic and IVUS measurements, showed a significant reduction in neointimal hyperplasia and late loss in the everolimus arm compared to the control arm. Between one and two-year follow-up, no additional death, myocardial infarction, clinically driven TLR, or TVR events were observed in the everolimus arm. The total MACE rate at two years for the everolimus arm remained 15.4%, which is in line with the SES and PES data. When comparing the everolimus group to the control group, the differences in MACE and TVF rate did not reach statistical significance, due to lack of power, however there was a clear trend in favour of the everolimus group.

Although, DES effectively reduce the need for repeat revascularisation compared to BMS, there are some concerns regarding the long-term safety of DES. Currently, the incidence of late (up to one year) and very late (after one year) stent thrombosis after DES placement is the subject of debate. The occurrence of stent thrombosis is a serious clinical event that in approximately 70% of patients leads to a MI and short-term mortality has ranged from 15% to 45%.24-26 As stent thrombosis is likely multifactorial in causality, several studies have identified premature discontinuation of dual anti-platelet therapy as a strong predictor for stent thrombosis.24-29 In this clinical evaluation, clopidogrel was only prescribed for a minimum of three months after stent implantation for both arms. Remarkably, no stent thromboses were reported in the everolimus or the control arm during two years follow-up.

Furthermore, delayed healing is identified as a contributing factor in developing late and very late stent thrombosis.30 In an autopsy study, first generation SES and PES showed significantly greater delayed healing characterised by persistent fibrin deposition and poorer endothelialisation compared to BMS.30 To provide a sufficient endothelialisation of the stent, it is inevitable to allow at least some late loss. In a porcine coronary model, everolimus-eluting stents, containing almost twice the doses everolimus per cm2 stent as used in this trial, showed 100% endothelialisation at 28 days post-implantation.31 In clinical studies, late loss data from the SES and PES showed a lower late loss for sirolimus.2,4-7,9 One-year QCA analysis of the SPIRIT FIRST trial, showed a late loss of 0.24 mm for the everolimus-eluting stent15 which is lower than the late loss as measured in PES and somewhat higher than SES.

Recently, the 6-month clinical and angiographic results of the SPIRIT II trial were published. The SPIRIT II is a single-blinded, multi-centre, non-inferiority, randomised (3:1) controlled trial evaluating the everolimus-eluting stent with the PES. The preliminary results of this trial support the short-term safety of the XIENCE V everolimus-eluting stent. At 6-month angiographic follow-up, the in-stent late loss was 0.11±0.27 mm in the everolimus arm and 0.36±0.39 mm in the paclitaxel arm.32 The SPIRIT II trial also schedules a two-year angiographic follow-up to collect more long-term efficacy data of the everolimus-eluting stent.

The angiographic results of the SPIRIT First trial and SPIRIT II trial show low late loss, with no stent thrombosis observed in the long-term results of the SPIRIT FIRST trial.

Due to the chemical structure, everolimus has a less extensive tissue penetration as compared to sirolimus,33 which is believed to be desirable in terms of local application of an anti-proliferative agent via a DES system. Additionally, during the first 28 days post-stenting, more than 75% of the dose of everolimus is released from the stent, with approximately 25% released during the first 24 hours and all is released after 120 days. This provides the everolimus-eluting stent with an effective but less aggressive coating.

Limitations of the study

The long-term clinical results of the SPIRIT FIRST trial with a small sample size provide limited safety and efficacy data. Large randomised, controlled studies of the everolimus-eluting stent for the treatment of coronary artery stenosis are currently under way in the US and Japan including the pivotal SPIRIT III clinical study. The 9-months clinical and 8-months angiographic follow-up results already presented, reaffirmed the short-term safety and efficacy data in a large patient population.34

Conclusion

This report confirms and extends the safety and efficacy results of the durable polymer XIENCE V everolimus-eluting stent up to 2-year as compared to identical bare metal stents.