Placebo-controlled trials of interventional procedures present additional recruitment challenges compared to placebo-controlled drug trials and unblinded interventional trials. This is related to the additional risks a placebo intervention might pose to patients without any potential for physical therapeutic benefit. Patient reluctance to participate can lead to difficulty in recruiting to target and time.

Many reasons are cited by patients and medical teams when they decline to participate in placebo-controlled trials. However, educating patients and medical teams can alleviate concerns and ensure that, with fully informed consent, patients choose to participate in research that can be practice changing.

Patients often cite the feeling that they need to know what treatment they have had as a reason to decline participation. This desire to know is amplified in an interventional trial compared to a drug trial because of the more invasive nature of the placebo intervention. For example, in trials of renal denervation, patients randomised to the placebo intervention still undergo renal angiography1. Trial participants need to be prepared to be discharged from hospital after a procedure with no knowledge of what treatment they have had; this is not acceptable for all patients.

Both clinicians and patients often cite a desire for the patient to receive the active treatment as a reason not to participate because the idea of deferral of an intervention is not palatable to them. Of course it is understandable for participants and their clinicians to prefer to be in the intervention arm because of the possibility of therapeutic benefit, but we rely on the altruism of patients to assess interventions accurately, without bias, in order to better treat the patients of the future.

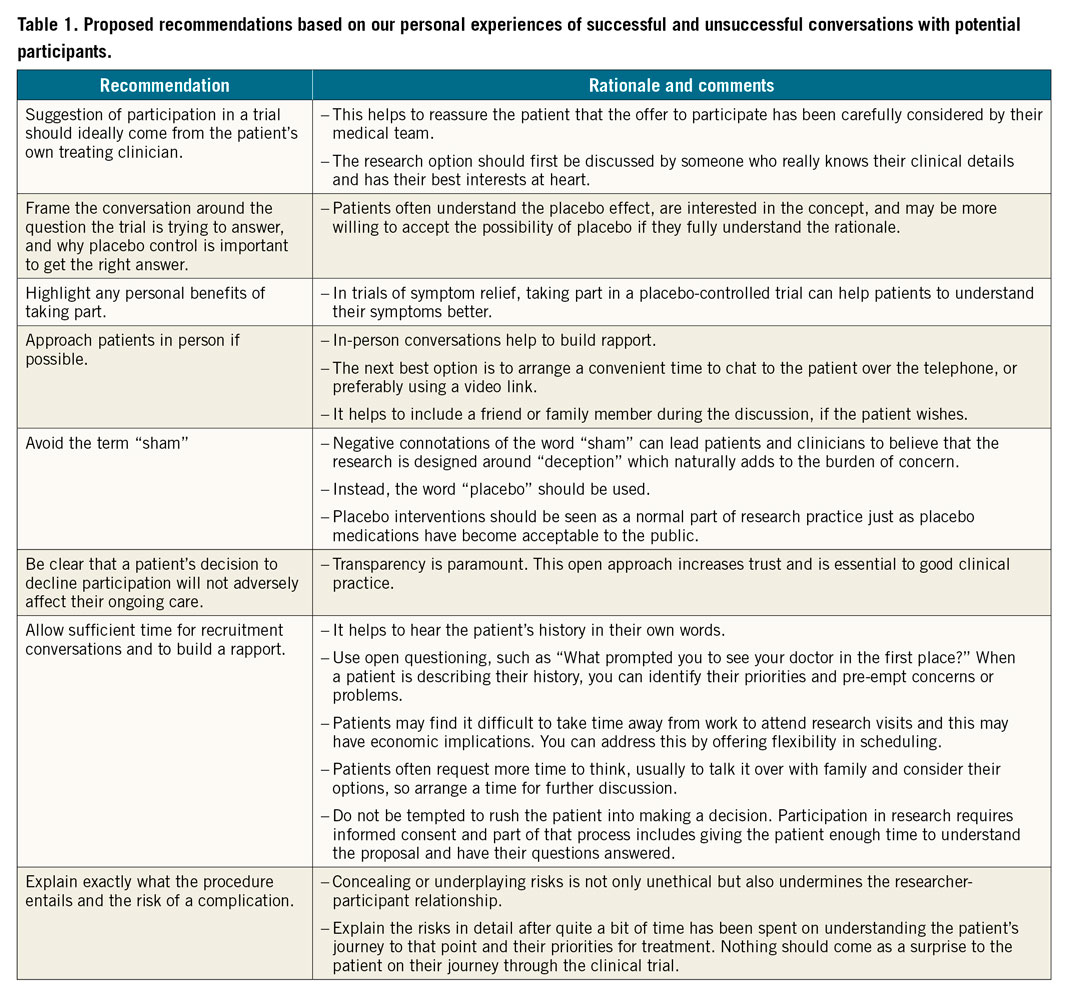

In this article we share our personal experiences of recruitment (Table 1) and how we have tried to address these issues in the placebo-controlled ORBITA2 and ORBITA-23 trials. These two trials randomise participants to either percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or placebo in the catheterisation laboratory immediately after invasive coronary angiography and pressure wire studies, and once a deep level of conscious sedation has been achieved. If randomised to placebo, the patient remains in the catheterisation laboratory with auditory isolation and sedation for at least 15 minutes, before removal of the sheath.

Trust building: the researcher-participant relationship

For any trial, participation relies on the researcher-participant relationship. Also there is a link between recruitment rates and the nature of the trial. For example, an internet survey may have a high participation rate despite the researchers developing no relationship with the participants. The more invasive or intrusive the study, the greater the number of study visits, or the higher the procedural risk, the more critical this relationship becomes. When the placebo intervention can carry risks which extend as far as death, the participant places a lot more trust in the research team.

Patients as partners

Patients often enjoy participating in trials. In particular, many are curious about the placebo effect and relish the chance to contribute to science. To harness this, we try to educate patients about why the trial is necessary and the potential impact it has for future patients. In designing ORBITA-2, we involved patients in the design, conduct and dissemination of future trial results. Our ORBITA focus group of previous participants was integral in shaping the aims, objectives and design of the trial. They also reviewed and amended all patient information literature and helped to design and pilot the smartphone app used in ORBITA-2. A former ORBITA patient was a co-applicant in grant applications and is a member of the trial steering committee. Engaging patients in research adds to the value of the research we produce and ensures that it remains patient focused and acceptable to potential participants.

Protocol considerations

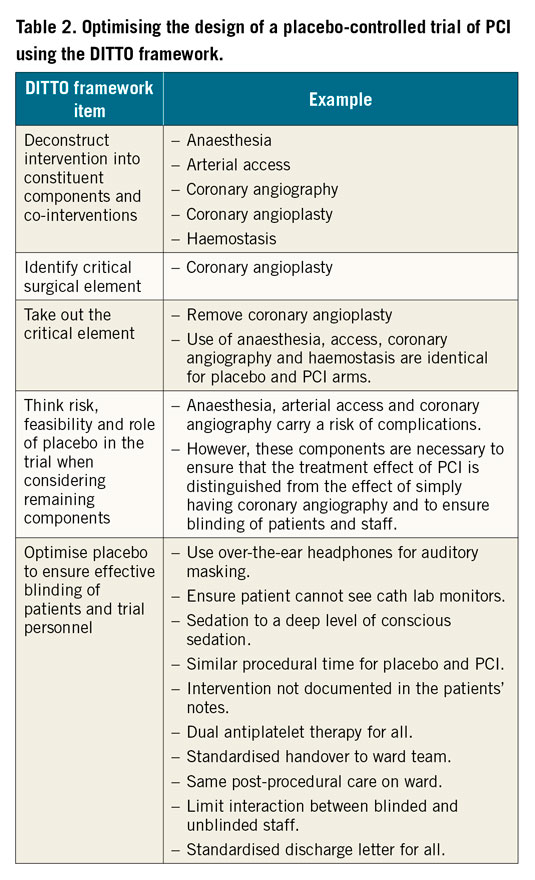

The placebo intervention has to be sufficiently similar to the active intervention so that the patient does not know what they have had but should also carry as low a risk as possible. Table 2 shows how the DITTO framework4 can be applied to designing a placebo-controlled trial using the example of a trial of PCI.

Trial management

Aside from trust and rapport building with the patient, management of the trial should be designed to remove barriers to participation. Here are some suggestions:

1. In trials designed to test existing therapies that form part of clinical practice, patients in the placebo arm should still be offered the active intervention once trial participation is complete.

2. All cost and time burden to partcipants should be minimised. Travel and refreshments, ease of access to medical care, and a dedicated contact telephone number for questions or concerns should be provided. It is important to allow flexibility in scheduling of study visits when approaching patients.

3. Ideally a patient should have one point of contact for the duration of the trial because, once they have built trust with a member of staff, it can feel disconcerting for the next visit to be handled by someone else. If the visit is going to be handled by someone else, the patient should be informed in advance.

As placebo-controlled trials become more frequent in procedural specialties, the need to recruit patients into these more complex trial protocols will become more important. Our personal experience of recruiting patients to placebo-controlled interventional trials has taught us that there are ways to improve recruitment rates and patient experience. With specific focus on the researcher-participant relationship and on the design of the study, these trials can be done and can provide novel data with the potential to have an impact on patient care.

Conflict of interest statement

R. Al-Lamee receives speaker’s honoraria from Philips Volcano, Abbott Vascular and Menarini Pharmaceuticals. C. Rajkumar is supported by the Medical Research Council. M. Foley is supported by the Medical Research Council. A.N. Nowbar is supported by the NIHR Academy.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.