Severe aortic stenosis (AS) is frequently present in the ageing population and is related to mortality and morbidity. Traditionally, this disease has been treated with surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR); however, during the last decade the field has been revolutionised by the less invasive transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). The number of TAVI procedures is increasing rapidly and, as the boundaries of TAVI are continuously pushed, there is an increased need for knowledge on how to deal with comorbidities.

Concomitant coronary artery disease (CAD) is a frequent comorbidity observed in up to 50% of patients selected for TAVI1. The presence of CAD does not seem to affect mortality2, and is only modestly predictive of the presence of angina3. Previous data from observational studies suggest that PCI in selected patients prior to TAVI does not affect mortality4. However, currently, there is no consensus on whether to treat CAD routinely with PCI upfront (pre TAVI) or to waive the PCI until symptoms eventually develop post TAVI. In European guideline recommendations for revascularisation in AS patients with significant asymptomatic coronary artery stenosis, undergoing TAVI is class II with a level of evidence C5. Other authors recommend that PCI should be performed prior to TAVI in any main vessel with a diameter stenosis >70%6. However, the available data are from relatively small non-randomised observational studies, something which carries a risk of (selection) bias. Moreover, in previous large randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in patients with stable CAD, PCI did not reduce mortality or myocardial infarction as compared to optimal medical therapy, but only reduced the incidence of repeat revascularisation7. Only in patients with proximal multivessel disease, that is proximal left anterior descending artery plus proximal right coronary artery or proximal left circumflex artery, revascularisation with PCI may exert an effect on mortality or myocardial infarction after 10 years8. Thus, PCI in patients with stable CAD is mainly performed to relieve symptoms. In contrast, TAVI clearly improves symptoms and reduces short- and long-term mortality and thus has a more pronounced effect than PCI in patients with severe AS and CAD.

PCI in patients with severe AS may also carry a higher risk for complications due to their comorbidities, e.g., poor renal function, reduced left ventricular function, peripheral arterial disease and prior stroke. In addition, coronary stenoses that are anatomically challenging PCI targets carry a higher risk of procedure-related complications and, consequently, are more prone to unsuccessful outcome. On the other hand, untreated coronary lesions subtending a significant amount of myocardium may induce profound ischaemia during TAVI and introduce the risk of haemodynamic instability during the procedure. Finally, PCI after TAVI may be more technically challenging because the valve prosthesis may limit the access to the coronary ostium.

Based upon solid evidence, the evaluation of CAD has changed from visual to physiological assessment using fractional flow reserve (FFR) or instantaneous wave-free ratio (iFR). However, physiological assessment in patients with AS is affected by a decreased coronary flow reserve that may affect both the FFR and iFR values. Regarding FFR, this may only affect a minority of patients in terms of the decision to perform PCI, since the FFR value changes across the 0.80 threshold pre vs. post TAVI in only 6% of cases9. Moreover, diameter stenosis in the intermediate to severe range (50-90%) poorly predicts haemodynamically significant stenosis both in patients with and in those without AS10. FFR therefore seems to be the best method for assessing the significance of CAD in patients with concomitant severe AS.

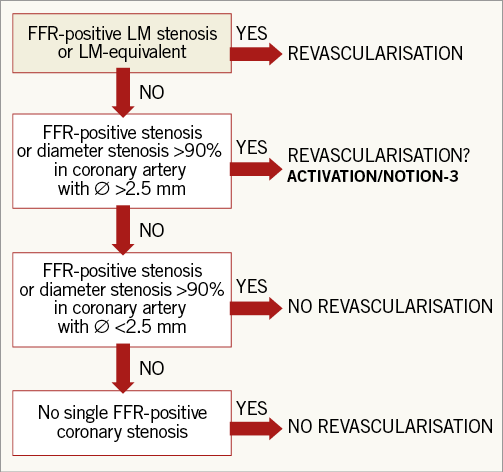

Thus, the question as to whether patients with CAD planned for TAVI should receive revascularisation by PCI and how the significance of the stenosis should be assessed remains unanswered. For many years now surgeons have performed SAVR plus coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) based on a level of evidence C. However, this strategy relies partly on the fact that CABG after SAVR would require re-sternotomy; PCI after TAVI carries a much lower risk due to the percutaneous nature of the procedure. RCTs are needed before any conclusion can be drawn with regard to timing of revascularisation in patients undergoing TAVI. The PercutAneous Coronary inTerventIon prior to transcatheter aortic VAlve implantaTION: a randomised controlled trial (ACTIVATION) will randomise patients with proximal CAD to either PCI plus TAVI or TAVI alone (www.clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT03424941). Another study, the Nordic Aortic Valve Intervention Trial - NOTION-3, will randomise patients with CAD to undergo FFR-guided PCI plus TAVI or TAVI alone (www.clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT03058627) (Figure 1). Hopefully, these important trials will help us to select the proper treatment strategy regarding revascularisation in patients with CAD undergoing TAVI.

Figure 1. Suggested algorithm for FFR-guided revascularisation before transcatheter aortic valve implanatation. FFR-positive: invasive fractional flow reserve ≤0.80; LCx: left circumflex; LM: left main

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.