Abstract

The management of coronary artery disease in the context of severe aortic stenosis in patients at increased surgical risk is an increasingly relevant problem in the transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) era. We review the current data on percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in TAVI patients and discuss how it has impacted upon our decision making, advocating that pre-TAVI revascularisation is not necessarily required.

Introduction

Senile, calcific aortic stenosis (AS) is the most common valvular disease in the developed world and often co-exists with coronary artery disease (CAD) secondary to atherosclerosis1,2. This has been the subject of numerous studies in the field of surgical aortic valve replacement, and revascularisation through concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting for significant lesions is recommended3. It is also of great interest to clinicians performing transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), given that these patients are generally older and are characterised by higher risk profiles. Looking to improve both safety and efficacy outcomes for these patients, the question now is whether or not these patients should be revascularised prior to TAVI.

Comparative pathophysiology

Calcific AS and CAD share common processes, such as the involvement of low-density lipoprotein-mediated immune response and inflammatory cytokine release4,5. The risk factors for both conditions are also similar, predominantly age, male sex, hypertension, smoking and raised low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels6. However, whilst one may be a marker of risk for the other7, the processes are distinct from each other. Indeed, the relevance of this common risk profile is evident when considering patients undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), where the incidence of CAD is known to increase with age and the degree of aortic calcification7-9.

TAVI and CAD

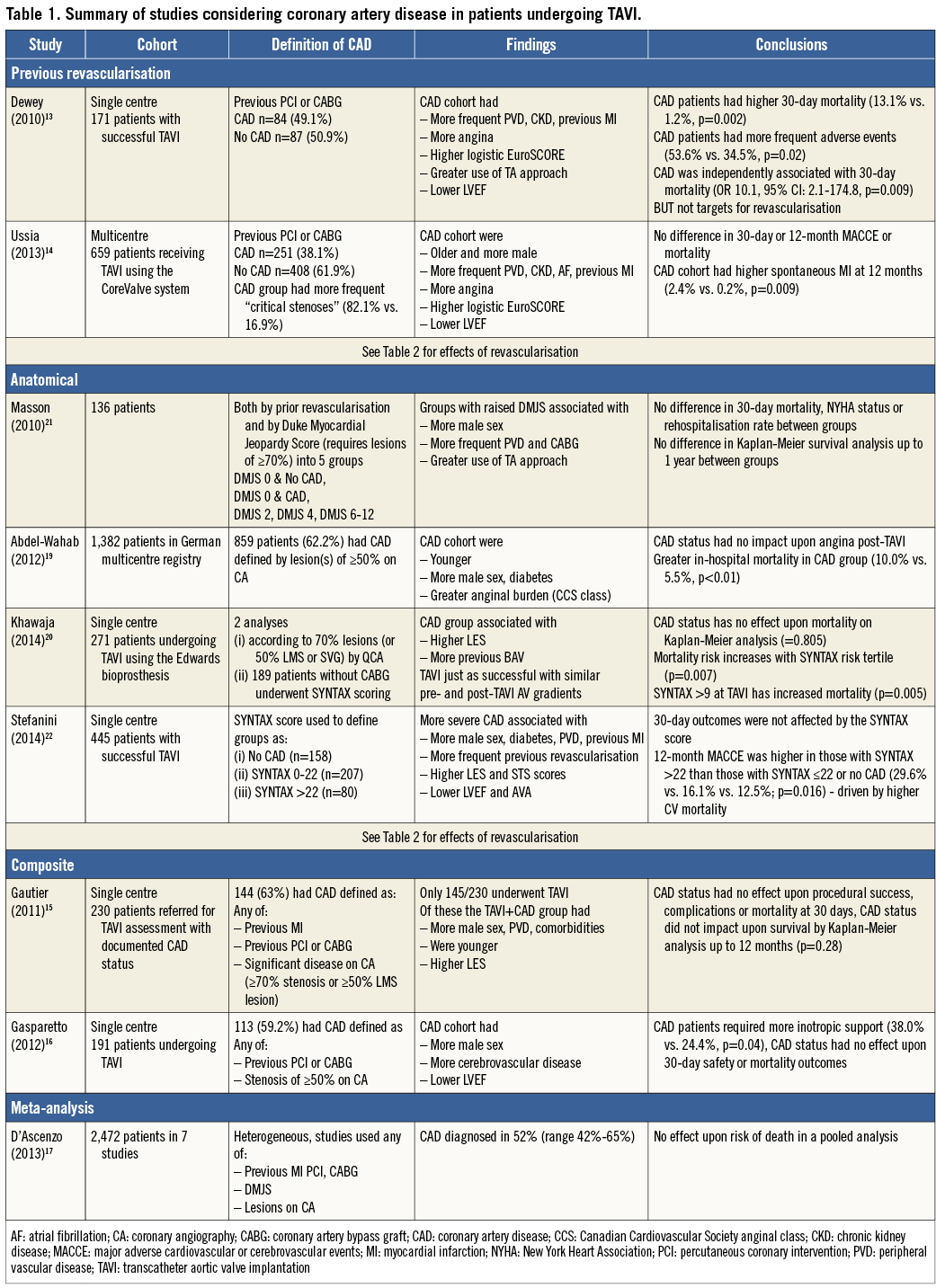

Given this overlap, it is not surprising that CAD is a frequent finding in patients undergoing TAVI in the larger registries and randomised controlled trials10-12. However, there is no consensus in the literature regarding the significance of CAD in patients undergoing TAVI, the main problem being the variability in the actual definition of CAD used in the specific studies, which are summarised in Table 1.

Some groups have used the presence of previous revascularisation to define CAD13,14. This seems to have identified patients at higher risk, with more frequent peripheral vascular disease (PVD), renal impairment, greater anginal burden and lower left ventricular ejection fraction13,14. Unsurprisingly, these studies also found higher perioperative risk in the CAD patients.

There are also analyses using composite definitions of CAD in the literature, combining factors such as previous revascularisation or myocardial infarction and angiographic severity of stenoses15,16. Again, these patients were found to have an increased frequency of comorbidities associated with CAD but with no impact upon survival. The limitations of heterogeneity may also explain the results of a recent meta-analysis combining many of these studies which also found no effect of CAD status upon mortality17.

Day by day in the cathlab we use anatomy to classify lesion severity prior to PCI and in assessing patients prior to SAVR3,18. Traditional cut-offs of stenosis severity, such as the 50% commonly used prior to surgery and 70% used in PCI, were found wanting in efforts to identify potentially modifiable risk factors19,20, as was the use of lesion position and severity in the Duke Myocardial Jeopardy Score to assess the volume of myocardium at risk21. The complexity of CAD as measured by the SYNTAX score, however, may be more promising, though whether the risk is modifiable by treatment is as yet unclear20,22.

Functional testing in the presence of aortic stenosis is more difficult, given the global subendocardial ischaemia which is often present. Myocardial perfusion scans can be falsely positive in up to 20% of cases23. Indeed, myocardial perfusion has been shown to be abnormal in the absence of coronary disease in severe AS on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging24. Fractional flow reserve is not validated in the presence of left ventricular hypertrophy or aortic stenosis25, though it has been used in a small case series26.

TAVI and PCI

PCI in patients with aortic stenosis has been shown to be feasible and safe in a historical cohort of 254 patients when compared to a propensity-matched cohort of patients without severe AS27. However, in this group of patients mainly comprising those with acute coronary syndromes or symptomatic angina thought to be predominantly due to CAD, those with LVEF ≤30% or an STS score ≥10 had a greatly increased 30-day mortality - an important consideration when approaching often high-risk patients for consideration for TAVI.

Historically, patients undergoing SAVR have been thought to benefit from concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Patients undergoing SAVR in early registries with unbypassed CAD have been shown to have poorer 10-year actuarial survival rates than those undergoing appropriate bypass or without the need of bypass28. There is, though, no randomised controlled trial to test this hypothesis in SAVR. However, the current guidelines suggest that myocardial revascularisation at the time of SAVR is a class I recommendation in the presence of stenoses of ≥70%, and a class IIa recommendation if the stenoses are 50-70% on angiography18. In the latest American guidelines this is a class IIa recommendation3. It should be noted that combined SAVR and CABG carries a greater risk than isolated SAVR29, possibly due to features of the procedure and also the characteristics of patients with CAD.

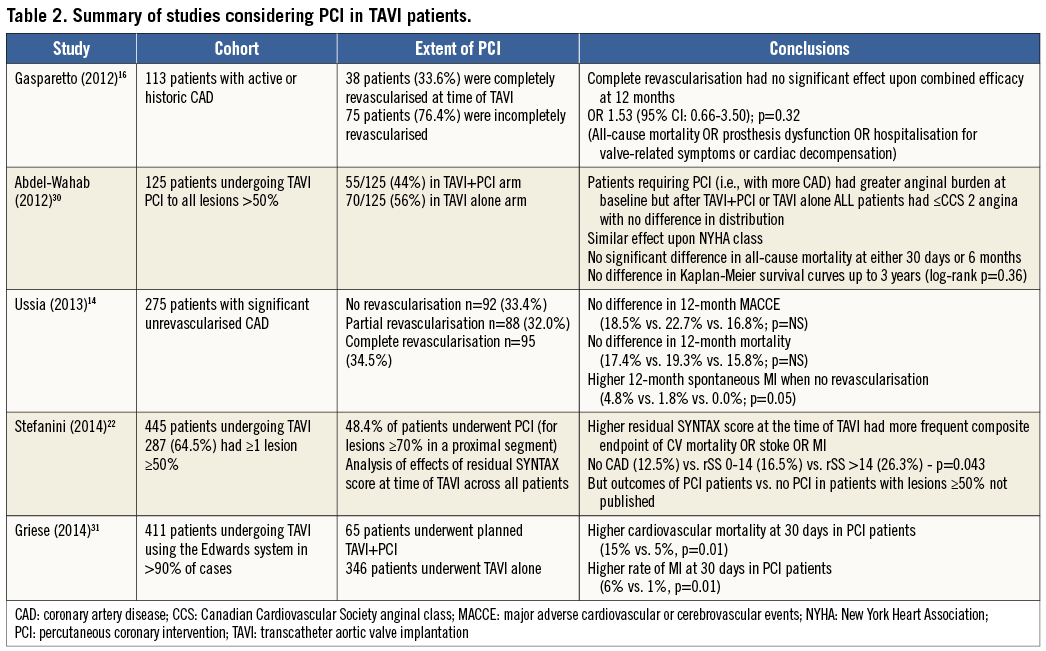

But does the degree of revascularisation have any effect upon outcome in TAVI? A subgroup analysis of the Italian CoreValve registry found that revascularisation prior to TAVI (whether complete or partial) resulted in 12-month MACCE and mortality no different from those who were not revascularised14. The absence of a mortality benefit for revascularisation has been reflected in subsequent, smaller studies16,22,30. In fact, there is evidence to suggest the opposite, with one recent study comparing the outcomes of 65 patients who underwent TAVI+PCI (either staged or combined) against 346 patients who received isolated TAVI. Thirty-day cardiovascular mortality was higher in the PCI arm (15% vs. 5%, p=0.01), as was the rate of myocardial infarction (6% vs. 1%, p=0.01), driven by periprocedural MI (5% vs. 1%, p=0.05). Staged PCI also had higher rates of blood transfusion (50% vs. 29%), although this did not reach statistical significance31.

With respect to the main indication for PCI in non-valvular stable coronary artery disease, namely the treatment of angina, again we find that PCI prior to TAVI does not seem to help. Despite more severe angina at baseline in the PCI cohort of a study of 129 patients (21% of patients were Canadian Cardiovascular Society [CCS] class 3-4, compared to only 8% of patients in the no PCI group [p=0.01]), post TAVI neither group had any patients with CCS >2 symptoms, and there was no difference between the PCI and no PCI arms30.

As to the question of timing of PCI, the vast majority of patients in these studies underwent PCI prior to TAVI in a staged procedure. Rates of hybrid PCI-TAVI are low in the reported literature at up to 14% of revascularisation, with the largest experience being only 46 patients30-34. However, the Pasic study did report promising one-year survival of 87.1% in this cohort, though without a comparator group to put that into context33. The most detailed inspection of this strategy was in the study by Griese et al. Outcomes and procedural details from 48 staged PCI were compared to 17 hybrid TAVI-PCI: they found no statistical difference between the groups with respect to 30-day outcomes, though the rate of myocardial infarction was higher in the hybrid group (12% vs. 4%) with the caveat of small numbers31. The results of PCI combining PCI and TAVI are summarised in Table 2.

What are the issues surrounding PCI in the context of TAVI?

Amongst the possible advantages of revascularisation prior to TAVI may be a protective effect against the ischaemic burden of the procedure, including, as it does, periods of hypotension. The absence of contractile reserve is associated with increased mortality after SAVR35, and significant stenoses not intervened upon could contribute to this. Improving coronary flow in symptomatic patients with significant flow-limiting stenoses may maximise this beyond the valvular intervention. Invasive coronary haemodynamic studies have demonstrated a marked reduction in the diastolic suction wave in AS, which significant coronary stenosis may impair further36.

The inherent risks of PCI are well-known to the cardiology community: death, myocardial infarction, stroke, vascular-access complications, renal insufficiency, allergy and stroke/TIA37,38. Even after successful PCI, there is the risk of stent thrombosis in up to 1% of cases with significant associated mortality39. PCI performed in the presence of severe aortic stenosis, whether staged or hybrid, runs the risk of the possibly detrimental effect AS may have upon the ability to withstand these. The need for dual antiplatelet therapy after PCI would be an important consideration in all access routes for TAVI, especially given the adverse outcomes associated with major bleeding40. Atrial fibrillation is common in these elderly patients, and so the issue of triple anticoagulation also arises to complicate matters. Acute kidney injury after TAVI is associated with increased mortality41, and the risks of contrast administration prior to TAVI should not be underestimated. Contrast use in coronary angiography within 24 hours of cardiac surgery has been shown to increase the risk of acute kidney injury (AKI)42. This risk can even extend out to five days43. Whether state or privately funded, the cost of a second admission in the case of staged PCI with an increased total length of stay must be taken into consideration.

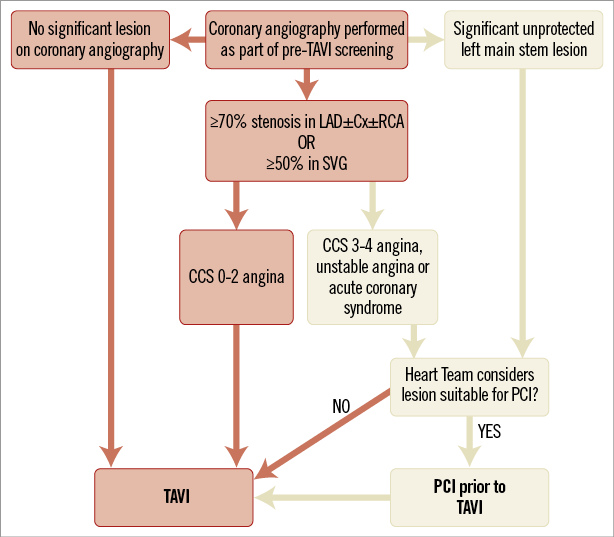

The literature does not currently support PCI prior to TAVI. Without data to suggest improved outcomes with PCI or revascularisation prior to TAVI, the inherent risks of PCI in patients with increased perioperative risk cannot be overlooked. As such, we have provided our own institutional algorithm (Figure 1), describing how PCI is reserved only for those in whom unstable coronary disease or the most severe angina is the presenting complaint (in our experience, an uncommon scenario with dyspnoea more prominent). Given that unprotected left main stem (ULMS) lesions carry the worst prognosis of any coronary lesion and given the increased myocardium at risk44, we would suggest that ULMS lesions should be considered by the Heart Team for revascularisation prior to TAVI irrespective of symptoms. Whilst applying this rationale in more than 450 patients, we have yet to require PCI for angina or its equivalents after TAVI. Perhaps the aorta is indeed the first coronary artery.

Figure 1. An algorithm to manage coronary artery disease in patients undergoing TAVI.

Access to the coronary ostia is possible with all the currently available commercial TAVI valves. However, one must carefully consider the relative anatomy of the aortic root, sinuses and the height of the ostia at the time of TAVI to ensure that future access is possible.

How to answer the known unknowns?

Randomised controlled trial data are clearly required. Both the PARTNER 2A and the Surgical Replacement and Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (SURTAVI) trials have revascularisation strategies within their designs. They will randomise patients between TAVI+PCI and SAVR+CABG if revascularisation is required.

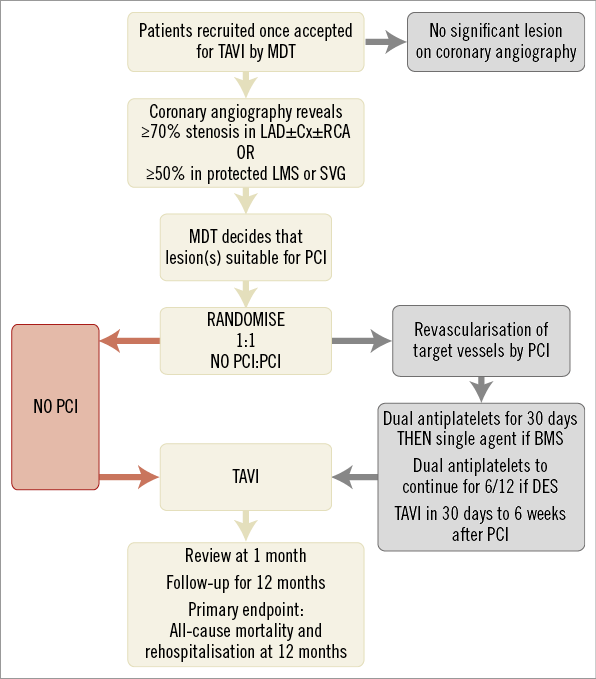

The issue of TAVI and CAD is to be addressed specifically by the percutAneous Coronary inTervention prIor to transcatheter aortic VAlve implantation (ACTIVATION) trial, a randomised, controlled, open-label trial of 310 patients who will be randomised to treatment of significant coronary artery disease by PCI (test arm) or no PCI (control arm) (Figure 2). Significant coronary disease is defined as ≥1 lesion of ≥70% severity in a major epicardial vessel, or 50% in a vein graft or protected left main stem lesion. The trial hypothesis is that a lack of pre-TAVI PCI is non-inferior to treating coronary stenoses with PCI prior to TAVI. The primary outcome is a composite of 12-month mortality and rehospitalisation, and the trial is currently enrolling in centres across the UK and France (ISRCTN75836930)44.

Figure 2. The structure of the ACTIVATION randomised controlled trial of PCI prior to TAVI (adapted from Khawaja et al)45.

Summary

Overall, the literature suggests that percutaneous revascularisation has not been shown to improve outcome after TAVI nor more ably reduce angina. Given the inherent risks detailed above in performing PCI and the lack of compelling data, we have postulated that pre-TAVI PCI can be omitted in these patients. Whilst data from ACTIVATION, PARTNER IIA and SURTAVI trials are awaited we have detailed our own strategy for managing CAD in our patients.

In our opinion the current data do not unreservedly support revascularisation in most patients awaiting TAVI and we would advocate a more hands-off approach.

Conflict of interest statement

M. Khawaja is in receipt of a British Heart Foundation Clinical Research Training Fellowship (12/15/29380). M. Khawaja, M. Thomas and S. Redwood have received research funding grants from Edwards Lifesciences and Boston Scientific. M. Thomas and S. Redwood are proctors for Edwards Lifesciences.