Abstract

Aims: Overlapping drug-eluting stents (DES) are frequently implanted to cover long segments of diseased and injured vessel, or as a bailout technique for edge dissection or incomplete lesion coverage. DES overlap is, nevertheless, associated with strut malapposition and poor intimal coverage, which may increase the risk of stent thrombosis. The aim of this study is to evaluate stent strut apposition in overlapping DES.

Methods and results: We assessed strut apposition in 10 overlapped segments (20 DES, 10 patients, 661 struts) immediately after implantation, using optical coherence tomography (OCT). Struts were defined as malapposed when no contact with the intima was detected by OCT, taking into consideration the strut thickness of each stent type.

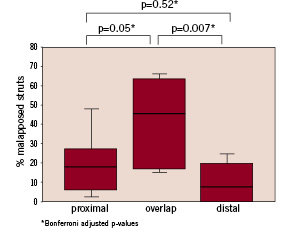

Despite aggressive stent optimisation using balloons with a final balloon/artery ratio of 1.26±0.18 at a maximum inflation pressure of 18.0±1.9atm, 41.8±21.5% of struts were malapposed in the overlapping segment, compared to 20.1±17.6% in the proximal and 9.7±10.6% in the distal segment (p < 0.05 for both).

Conclusions: OCT revealed that 40% of struts within an overlapped DES segment were malapposed, and this may explain the reported delay in endothelialisation in such segments.

Introduction

Coverage of the entire injured and diseased vessel segment is an established principle in the deployment of drug-eluting stents (DES) and a key factor in optimising DES efficacy to limit restenosis. This strategy requires stent coverage from the least-diseased to least-diseased segments, thus demanding the implantation of multiple stents when lesions are long. Implantation of multiple overlapping stents is also required following initial DES implantation when extensive dissection or residual stenosis is present. The use of overlapping stents may lead to local arterial toxicity with exposure to inappropriately high levels of anti-proliferative drug or polymer. This phenomenon remains a concern and may predispose to delayed endothelialisation. Moreover, overlapping layers of stent struts and sub-optimal stent expansion and apposition to the intima can also lead to stent thrombosis.1 Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a new intravascular imaging modality, which uses infrared light and offers ten-fold higher resolution (10-15 m) and fewer artefacts compared to intravascular ultrasound, thereby enabling precise assessment of stent optimisation.2,3 The present study aimed to assess the frequency of DES strut malapposition within overlapped segments immediately following implantation and angiographic optimisation.

Methods

Study population

Between February and October 2006, 10 patients who received overlapping DES were assessed using OCT (20 stents, 10 lesions). The OCT examination took place following angiographic optimisation. Overlapping DES was used as a primary strategy for very long lesions or bailout for residual stenosis or dissection following the implantation of the first stent. Pre-dilatation or direct stenting and selection of stent type were left to the discretion of the operator, but the same type of DES was used for each lesion and stent implantation was always followed by high-pressure post-dilatation at the overlapping segment. Stent optimisation was accomplished with conventional angiographic guidance aiming at a residual diameter stenosis < 20% by visual estimate.

OCT procedure

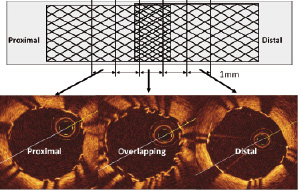

The OCT system used in this study (LightLab Imaging Inc., Westford, MA, USA) has been described previously.3,4 In brief, lesions were imaged during proximal occlusion and continuous infusion of Ringer’s lactate at 0.5-1.5 ml/sec. An OCT catheter (Helios™ proximal occlusion catheter) and an OCT imaging wire (ImageWire™) were used. The lesion was visualised with an automated pullback system at 1.0 mm/sec acquiring cross sectional images at 15.4 frames/sec. Off-line analysis of contiguous cross-sections in overlapped stents was performed at 1 mm intervals. The overlapped struts were assessed as well as the two adjacent cross-sections immediately proximal and distal (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schema of two overlapped stents demonstrating the areas assessed using optical coherence tomography.

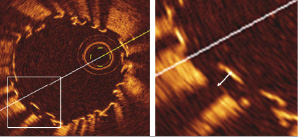

Strut malapposition was defined as no contact between the strut and intima. As OCT can show only the surface of stent struts due to its limited penetration through the metal, the measured distance between the strut surface and the luminal surface (Figure 2) was adjusted based on each stent thickness.

Figure 2. Measurement of distance between the endoluminal surface of the strut and intima. Note that OCT can only show the endoluminal surface of the strut due to its limited penetration through metal.

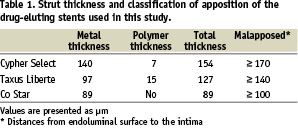

Each cut-off was determined as the total of the metal and polymer thickness plus 10 m (OCT longitudinal resolution) (Table 1).

Struts protruding into the ostium of a side branch were excluded from the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R version 2.4.1 and StatView 5.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Comparison between groups was performed using the Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test, followed by pairwise Wilcoxon rank sum tests with Bonferroni correction. A two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was used as the criterion for statistical significance.

Results

Clinical and lesion characteristics

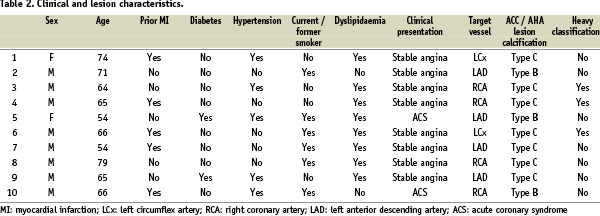

Table 2 lists the clinical and lesion characteristics for the 10 patients.

All lesions studied were complex (ACC/AHA classification type B or C), including three severely calcified lesions. Cypher Select (Cordis, Johnson and Johnson Co., Miami Lake, FL, USA), CoStar (Conor Medsystems, Inc., Hamilton Court Menlo Park, CA, USA) and Taxus Liberte (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) stents were used in this study. There were no OCT-related complications such as haemodynamic instability or arrhythmias during image acquisition and no subsequent deterioration of flow or coronary dissection.

Angiographic and procedural characteristics

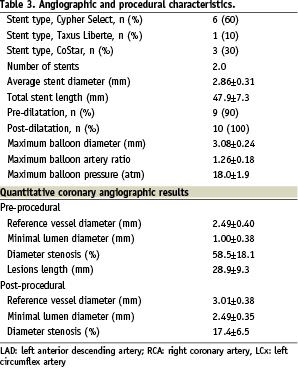

Table 3 lists the angiographic and procedural characteristics.

The mean number of stents used per lesion was 2.2±0.4. In only one case was direct stenting performed. Mean total stent length was 47.9±7.3 mm. Post-dilatation was used in all cases with non-compliant balloons at a mean pressure of 18.0±1.9 atm. The balloon to artery ratio was 1.26±0.18. In 8 of 10 patients (80%), the distal stent was implanted first followed by the proximal stent in an overlap fashion.

OCT analysis

A total of 661 struts in 53 cross sections were analysed (239 struts in the overlapping segment, 228 struts in the proximal segment and 194 struts in the distal segment). The proportion of malapposed struts differed significantly between the overlapped (41.8±21.5%) and both the proximal (20.1±17.6%) and distal (9.7±10.6%) non-overlapped segments (Kruskal- Wallis p=0.003, Figure 3).

Figure 3. Percentage of malapposed struts in the overlap segment and in the proximal and distal segments immediately adjacent to the overlap.

Discussion

Using high resolution intravascular imaging with OCT, our study has shown that a high proportion of the stent struts located within an overlapped segment remain malapposed, despite high pressure balloon dilatation with appropriately sized balloons. Furthermore, the region immediately proximal to the overlap segment has a greater number of malapposed struts.

OCT is a new intravascular imaging modality, which uses infrared light and offers 10 times higher resolution (10-15 µm) and fewer artefacts compared to IVUS. The clinical application of intracoronary OCT has already been demonstrated both in stable patients and in those with acute coronary syndromes5 and was used without complication in our patients.

The high malapposition rate in the overlap segment immediately following DES implantation and aggressive optimisation is an important finding and one that has not previously been reported using OCT. Prior studies have raised concerns regarding the safety of overlapping DES, with particular reference to the phenomenon of ‘double dose’ of metal, polymer and drug in this stented segment.6 One third of patients enrolled in SIRIUS, E-SIRIUS and TAXUS-VI study received multiple overlapping stents.7-9 In a recent pooled analysis of five clinical trials of the sirolimus-eluting stent (SES), 575 patients with stent overlap (337 SES, 238 BMS) were compared to 1,162 patients with single stents (697 SES, 465 BMS).6 Stent overlap was associated with a greater late lumen loss in-stent and more frequent angiographic restenosis, regardless of stent type.6

Concerns that stent overlap may increase the likelihood of stent strut malapposition and thus the propensity for restenosis and thrombosis therefore remain unanswered. Animal studies, showed persistent inflammation and fibrin deposition even with full endothelial healing or delayed endothelialisation following DES implantation compared with bare metal stents, particularly at overlapping segments.10,11 This may be related to excess inhibition of neointimal hyperplasia as a result of the double dose of sirolimus. Using OCT six months after SES implantation, Matsumoto et al12 found that overlapping SES struts showed malapposition more frequently than did non-overlapping struts. The clinical significance of this however remains unclear, particularly as this study did not assess stent strut apposition at implantation.

In our study, we noticed a difference in the number of malapposed struts in the proximal segment adjacent to the overlap segment compared to that immediately distal. This did not reach statistical significance, likely as a result of the small number of cases included, however it is an interesting observation and one that warrants further investigation and discussion. This phenomenon may be the result of vessel tapering or the deployment order of the overlapping stents. Since coronary dilatation balloons and stents have a longitudinally uniform size, it is less likely that struts in the proximal part of the stent become optimally apposed to the intima. Furthermore, when the intended strategy is that of overlapping stents, the distal stent is usually implanted first followed by the proximal stent. This may result in a funnelling effect with the proximal stent expansion being restricted by the already deployed distal stent. Deployment of the proximal stent first may limit this, however, may prove technically challenging. Larger studies will help delineate this observation further.

Limitations

This was an observational study with a small sample size. For this reason, this report was limited to individual patient data and few overall summary statistics and comparisons. The sample size also precludes any formal assessment of predictors of strut malapposition in overlap segments with larger studies needed to address this and other concerns related to the long-term issues of DES safety and any differences that may exist between different stent platforms.

Conclusions

This preliminary study has shown that overlapping DES is associated with a considerable risk of immediate stent strut malapposition. Moreover, the segment proximal to the overlap appears more prone to malapposition compared to the distal stented segment, despite aggressive stent optimisation using adequately sized balloons with high pressures. This phenomenon, never before documented, may contribute to delayed endothelialisation and result in an increased risk of stent thrombosis although larger studies are needed to confirm these findings and determine their relation to late DES complications.