Abstract

Aims: The risk assessment tools currently used to predict mortality in transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) were designed for patients undergoing cardiac surgery. We aimed to assess the accuracy of the TAVI dedicated risk score in predicting mortality outcomes.

Methods and results: Consecutive patients (n=1,038) undergoing TAVI at a single institution from 2014 to 2016 were included. The ACC/TVT registry mortality risk score, the STS-PROM score and the EuroSCORE II were calculated for all patients. In-hospital and 30-day all-cause mortality rates were 1.3% and 2.9%, respectively. The ACC/TVT risk stratification tool scored higher for patients who died in-hospital than for those who survived the index hospitalisation (6.4±4.6 vs. 3.5±1.6, p=0.03, respectively). The ACC/TVT score showed a high level of discrimination, C-index for in-hospital mortality 0.74, 95% CI: (0.59-0.88). There were no significant differences between the performance of the ACC/TVT registry risk score, the EuroSCORE II and the STS-PROM score for in-hospital and 30-day mortality rates.

Conclusions: The ACC/TVT registry risk model is a dedicated tool to aid in the prediction of in-hospital mortality risk after TAVI.

Abbreviations

ACC/TVT: American College of Cardiology/Transcatheter Valve Therapy

AS: aortic stenosis

CI: confidence interval

GFR: glomerular filtration rate

LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction

SAVR: surgical aortic valve replacement

STS-PROM: Society of Thoracic Surgeons - predicted risk of mortality

TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation

VARC-2: Valve Academic Research Consortium-2

Introduction

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has emerged as an option for patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS) at elevated risk for surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR)1-3. In clinical practice, the Heart Team estimates risk for SAVR/TAVR utilising a combination of clinical judgement, frailty indices, and various surgical risk calculators such as the Society of Thoracic Surgeons - predicted risk of mortality (STS-PROM) score, the logistic EuroSCORE and the EuroSCORE II4-7. However, these risk scores, designed for surgical risk assessment, have not been validated in transcatheter interventions and their ability to predict risk for TAVI is unclear8,9. Recently, a dedicated TAVI risk model has been developed based on the data from the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/Transcatheter Valve Therapy (TVT) registry10. The aim of the present study was to compare the accuracy of the STS-PROM, EuroSCORE II, and ACC/TVT risk scores in predicting outcomes from a large population of TAVI patients.

Methods

From January 2014 to November 2016 all patients with severe AS who underwent TAVI at our institution (n=1,038) were identified. Decisions regarding risk and candidacy for TAVI were made by a dedicated Heart Team.

Severe AS was defined as a valvular orifice area <1.0 cm2 or <0.6 cm2/m2 and/or mean pressure gradient >40 mmHg and/or jet velocity >4.0 m/s. Selected patients with discordant echocardiographic findings underwent dobutamine echocardiography.

Patients were assessed by echocardiography, coronary angiography, and gated cardiac computed tomography. If vascular anatomy was unsuitable for a transfemoral approach alternative accesses were considered.

The ACC/TVT risk score, the STS-PROM score, and the EuroSCORE II were calculated for all patients11-13. Variables and endpoints of the ACC/TVT risk prediction tool, the STS-PROM score and the EuroSCORE II are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Events were collected in a dedicated database during the index hospitalisation, at 30-day follow-up and at one year. Endpoints were adjudicated according to the Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 (VARC-2) definitions14. The Columbia University Institutional Review Board approved the retrospective chart reviews of all patients and waived individual patient consent.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The primary outcomes were in-hospital and 30-day all-cause mortality. Descriptive data are presented as means and standard deviations for continuous data or frequencies and percentages for categorical data. For univariate analysis, t-tests were used to compare the continuous variables and Pearson’s chi-square tests were performed for categorical variables to determine the associations between in-hospital mortality and/or 30-day mortality with baseline demographic, echocardiographic and TAVI procedural characteristics.

Discriminatory abilities of the models were assessed using the C-index. The C-index ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating better discrimination. A non-parametric DeLong method was used through the ROCCONTRAST option in PROC LOGISTIC (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) to compare two ROC curves. We examined the predictive accuracy of the ACC/TVT risk score vs. EuroSCORE II, ACC/TVT registry score vs. STS-PROM score, EuroSCORE II vs. STS-PROM score for in-hospital mortality and 30-day mortality using the DeLong method. Calibration of the models was evaluated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow χ² statistic goodness-of-fit test, which compares observed and predicted outcomes over deciles of risk and also the observed probability with the expected probability within each decile, with a value <0.05 indicating significant difference in expected versus observed mortality. Analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

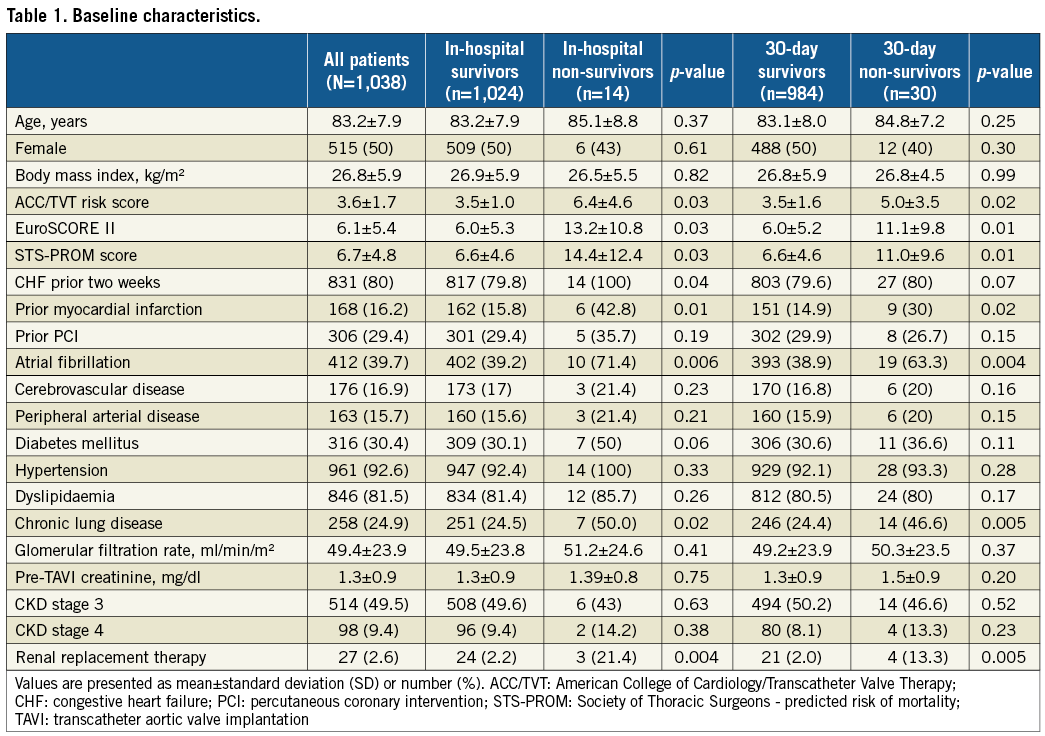

We analysed the outcomes of 1,038 consecutive patients (female 49.6%) treated with TAVI between January 2014 and December 2016. In-hospital and 30-day survival status was available in 100% and 99.3% of patients, respectively. In-hospital and 30-day mortality rates were 1.34% and 2.9%, respectively. Baseline characteristics of survivors in comparison to non-survivors are presented in Table 1. In-hospital non-survivors were more likely to present with heart failure than in-hospital survivors (14 [100%] vs. 817 [79.8%], p=0.04). They also demonstrated higher rates of prior myocardial infarction (MI) (6 [42.8%] vs. 162 [15.8%], p=0.01), atrial fibrillation (10 [71.4%] vs. 402 [39.2%], p=0.006) and chronic lung disease (7 [50%] vs. 251 [24.5%], p=0.02) than in-hospital survivors.

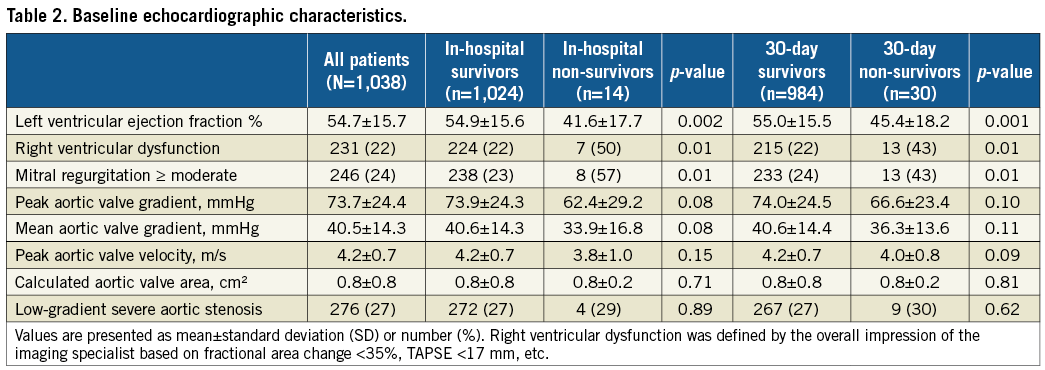

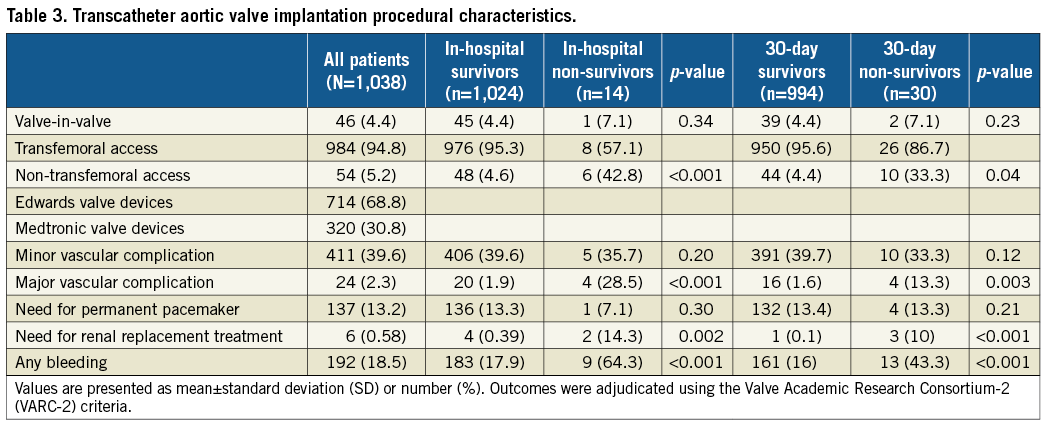

Baseline echocardiographic features are presented in Table 2. Survivors in comparison to non-survivors had higher left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at baseline (55±16% vs. 42±18%; p=0.002) and at 30-day follow-up (55±15.5% vs. 45±18%; 0.001) as well as lower rates of right ventricular dysfunction (at baseline, 224 [22%] vs. 7 [50%], p=0.01, and at 30 days, 215 [22%] vs. 13 [43%], p=0.01) (Table 2). Non-transfemoral access was associated with higher mortality rates (48 [4.6%] vs. 6 [42.8%], p<0.001, and 44 [4.4%] vs. 10 [33.3%], p=0.04), for survivors vs. non-survivors during hospitalisation and at 30-day follow-up, respectively. Major vascular complications were significantly higher in non-survivors in comparison to survivors (4 [28.5%] vs. 20 [1.9%], p<0.001 for in hospital non-survivors vs. survivors, respectively) (Table 3).

Mean ACC/TVT registry risk score and EuroSCORE II predicted a relatively high in-hospital mortality, 3.6±1.7% and 6.1±5.4%, respectively, in comparison to the 1.3% in-hospital mortality registered among our cohort of patients. Predicted 30-day mortality rates according to STS-PROM score were 6.7±4.8% in contrast to the lower actual 30-day mortality rates of 2.9%. The ACC/TVT risk stratification tool scored higher for patients who died in hospital than for those who survived (6.4±4.6 vs. 3.5±1.6, p=0.03, respectively).

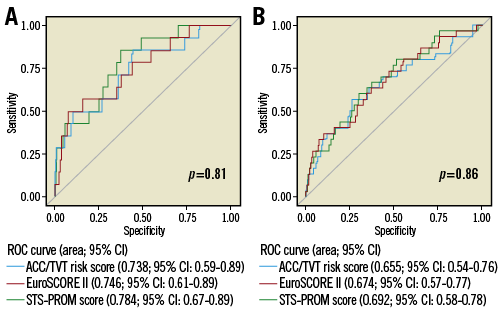

The ACC/TVT registry risk score showed a high level of discrimination (C-index for in-hospital mortality area under the curve [AUC] 0.74, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.59-0.88) (Figure 1A). The C-index statistics for in-hospital mortality of the EuroSCORE II and 30-day mortality of the STS-PROM score are shown in Figure 1A and Figure 1B, respectively. There were no significant differences in the predictive performances of the ACC/TVT registry risk score, the EuroSCORE II and the STS-PROM score for in-hospital and/or 30-day mortality rates. A comparison of the discriminative performance of the ACC/TVT registry risk score vs. the EuroSCORE II vs. the STS-PROM score for in-hospital and 30-day mortality is presented in Figure 1A and Figure 1B, respectively.

Figure 1. Comparison of the discrimination ability of the TVT registry risk score, EuroSCORE II, and STS-PROM score. A) In-hospital mortality. B) 30-day mortality.

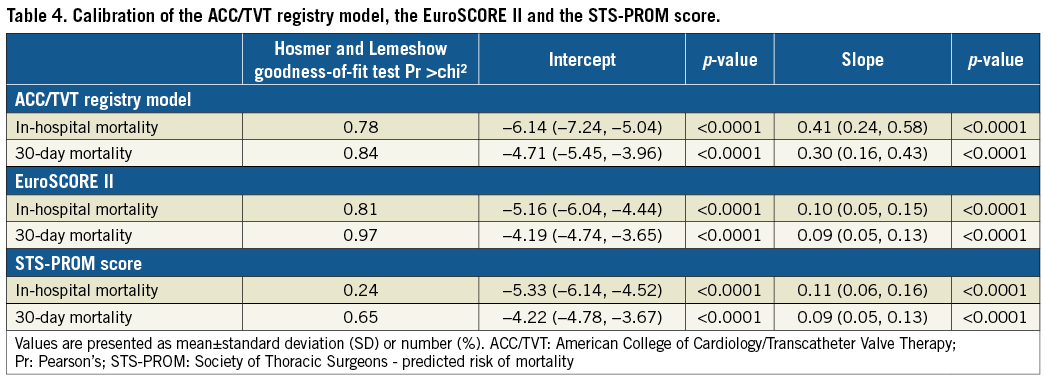

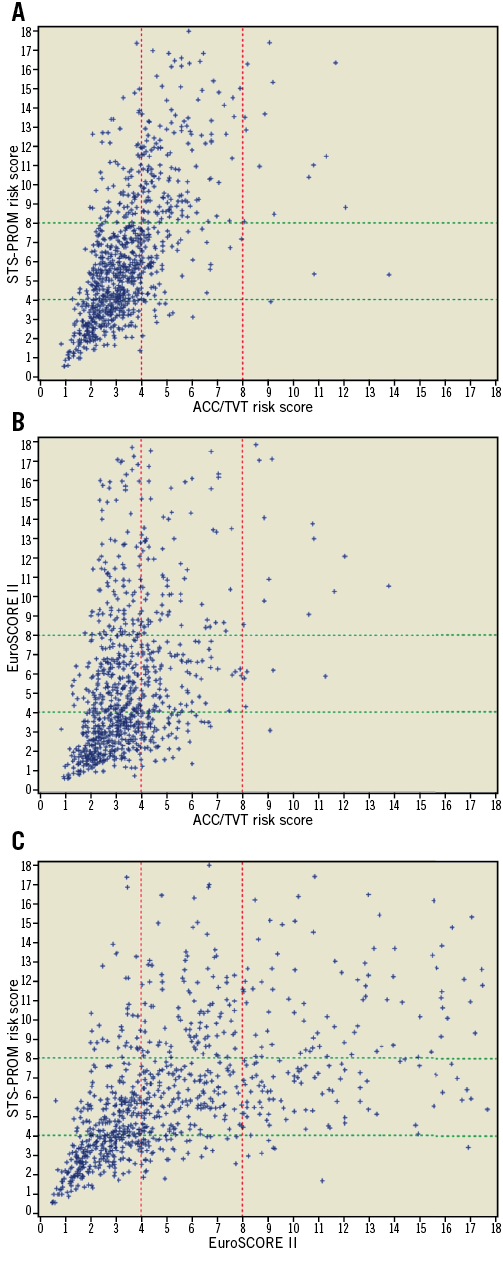

The calibration of the ACC/TVT risk prediction tool was accurate for in-hospital and 30-day mortality (Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit 0.78, intercept –6.14 [–7.24, –5.04], p<0.0001 for in-hospital mortality and Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit 0.84, intercept –4.71 [–5.45, –3.96], p<0.0001 for 30-day mortality) (Table 4). The ACC/TVT registry risk score showed a calibration slope of 0.4 and 0.3 for in-hospital and 30-day mortality, respectively. The calibration slope of the EuroSCORE II was 0.1 for in-hospital mortality and 0.09 for 30-day mortality, and the calibration slope of the STS-PROM score was 0.11 and 0.09 for in-hospital and 30-day mortality, respectively. The higher calibration slope of the ACC/TVT registry provides a better sensitivity in comparison to the EuroSCORE II and the STS-PROM score (Table 4). Dispersion graphs showing the correlation of the STS-PROM score and the EuroSCORE II to the ACC/TVT risk score are presented in Figure 2A and Figure 2B, respectively. The correlation of the STS-PROM score to the EuroSCORE II is presented in Figure 2C.

Figure 2. Comparison of the TVT registry risk score, EuroSCORE II, and STS-PROM risk score’s calculated expected mortality. Panels A and B show that the EuroSCORE II and STS-PROM models’ expected mortality was higher than that of the TVT registry model. Panel C shows that the EuroSCORE II and STS-PROM scores were more correlated.

Discussion

This study sought to validate the STS/ACC TVT registry risk model for predicting in-hospital mortality in 1,038 patients who underwent TAVI between January 2014 and December 2016, and to compare the performance of this risk model to the performances of the STS-PROM and EuroSCORE II risk models for predicting mortality.

The primary findings are as follows. 1) The ACC/TVT performed as well as the STS-PROM score and EuroSCORE II, and there were no significant differences in the performance metrics of these models. 2) The ACC/TVT, STS-PROM and EuroSCORE II risk assessment tools predicted higher than the actual mortality rates. 3) Calibration was accurate for the three evaluated models with a higher calibration slope registered for the ACC/TVT. 4) Dispersion graphs demonstrated good correlation between the STS-PROM and the EuroSCORE II models but, when compared to the ACC/TVT registry model, both surgical models tended to place patients at higher risk than the ACC/TVT risk model. 5) Non-survivors had higher rates of LV dysfunction, right ventricular dysfunction, chronic lung disease, congestive heart failure, prior MI, atrial fibrillation and non-transfemoral access as well as higher rates of bleeding and major vascular complications.

This study demonstrated that the ACC/TVT registry risk model is equivalent to the STS-PROM score for predicting in-hospital mortality. The ACC/TVT registry model showed good calibration along with numerically (not statistically significant) higher discrimination than the STS-PROM model. However, as the ACC/TVT registry model predicts in-hospital and the STS-PROM model predicts 30-day mortality, the two scores predict different parameters of the risk-benefit analysis. The EuroSCORE II, which is validated to predict in-hospital mortality, did not differ significantly from the ACC/TVT model.

Previous TAVI risk models have been developed15-18. Although reported to have good discrimination, they are limited by their small derivation cohorts. The ACC/TVT registry derived and validated its risk model in a population of 13,718 and 6,868, respectively10.

Herein, patients underwent TAVI from January 2014 to November 2016, while the TVT database included procedures from January 2011 to February 2014. Therefore, our cohort of patients does not significantly overlap with the ACC/TVT registry. Patients treated recently probably received newer-generation devices and delivery catheters and were treated by operators with greater experience.

Shorter hospital stays in contemporary patients (as against derivation) may also affect in-hospital mortality figures. Future models should be called to look at mortality at specific time points (i.e., 30 days, one year, etc.).

In accordance with our findings, other studies also predicted higher than the actual mortality rates. In the PARTNER B trial, the average STS-PROM score for patients undergoing TAVI was 11.2%, while actual in-hospital mortality was 1.7% and 30-day mortality was 6.4%1. This was also noted in the PARTNER A and in the more recent PARTNER 2 and SURTAVI trials studying patients at intermediate risk2,3,19. In our cohort, the average STS-PROM score and EuroSCORE II were 6.7 and 6.1%, respectively, while actual mortality rates were 1.3% (in-hospital) and 2.9% (30 days). The ability of any risk score to predict mortality accurately in patients undergoing TAVI remains limited as the field rapidly evolves and mortality rates continue to decline. Our study showed that the ACC/TVT registry risk model, the STS-PROM score and the EuroSCORE II may already be dated.

The strength of the ACC/TVT risk model lies in the fact that it was derived and validated utilising patients undergoing TAVI, whereas the STS-PROM score and EuroSCORE II were developed using outcomes in patients undergoing cardiothoracic surgery4-7. Another strength of the model is its easy clinical applicability with only seven variables11. However, its limitations include absence of measurements of frailty; it is currently used to predict in-hospital mortality. A 30-day risk calculator is being developed and this will allow direct comparison between the STS-PROM and the ACC/TVT risk scores20.

This study also included dispersion graphs to provide a visual aid to assess the correlation among the three risk models. Patients located in the superior left and inferior right parts of the graphs showed poor correlation. The dispersion graphs show a correlation between the STS-PROM score and EuroSCORE II for most patients. When either of these is compared to the ACC/TVT registry risk model, the STS-PROM score and EuroSCORE II tend to score higher, and far more patients are located in the superior left part of the graph, indicating a higher score than by using the ACC/TVT registry risk score. These differences can be explained by the presence of certain variables in the surgical risk scores that are not included in the ACC/TVT registry risk model. Previous cardiothoracic surgery is of importance when considering surgical AVR and is included in the STS-PROM and EusoSCORE II calculators; however, patients undergoing TAVI do not face the same risk, as the procedure is minimally invasive, hence this variable is not included in the ACC/TVT registry risk calculator. Moreover, LVEF %, peripheral artery disease, active endocarditis and other parameters are included in both surgically derived risk prediction tools but not included in the ACC/TVT registry risk model11-13.

Limitations

This is a single-centre study so generalisability is a limitation. Although we were able to include 1,038 patients, our population was still small compared to the original risk model derivation and validation cohort populations. In addition, the number of events was relatively low. Therefore, our ability to show differences among scores may be limited. However, our population was diverse and large enough to demonstrate good discrimination and to reassure that no significant differences exist among the risk models. Another limitation of our study was the exclusion of the frailty index. While the risk-benefit assessment for TAVI is still evolving, we should keep in mind that a sizeable group of patients does not fully benefit from the intervention in terms of quality-of-life measures. Future prediction scores should also focus on and facilitate identifying patients who would gain quality-of-life benefits from TAVI21.

Although we were able to show that the ACC/TVT registry risk model has slightly better discrimination than the STS-PROM risk model, this conclusion is limited because clinical practice includes both the STS-PROM risk score and frailty index in the risk-benefit analysis discussion. Lastly, our population was at intermediate risk (average STS-PROM 6.7%). As TAVI indications expand to include lower-risk populations, further iterative derivation/validation processes and studies will be required to validate the ACC/TVT registry risk model, as well as other models.

Conclusions

In a large, diverse population, the validation of the ACC/TVT registry risk model demonstrated good discrimination for the prediction of in-hospital mortality and was not significantly different from the STS-PROM risk score for 30-day mortality. Therefore, the ACC/TVT registry risk model should be considered as an alternative to the STS-PROM risk model to guide future risk-benefit analysis discussions in patients eligible for TAVI.

| Impact on daily practice As TAVI indications expand towards intermediate- and low-risk patients, a reliable and easy to use risk stratification tool, dedicated and validated for TAVI patients, is of major importance in order to inform patients, discuss expectations of treatment and report results. In our study, we compared the predictive accuracy of the ACC/TVT risk score to the surgical EuroSCORE II and STS-PROM score. From the analysis of our large and diverse population of patients, the ACC/TVT registry risk model demonstrated good discrimination for the prediction of in-hospital mortality and was not significantly different from the STS-PROM risk score for 30-day mortality. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Matthew Brinkman and Liao Ming for their great contribution to the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

This research study was self-funded by the Department of Cardiology of the Columbia University Medical Center & NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, New York, USA.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary data

Supplementary Table 1. Variables and endpoints of the ACC/TVT registry risk score, the STS-PROM risk score and the EuroSCORE II.

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.