Abstract

Aims: To highlight differences between the most recent guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) on the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

Methods and results: ESC 2012 and ACCF/AHA 2013 guidelines on the management of STEMI were systematically reviewed for consistency. Recommendations were matched, directly compared in terms of class of recommendation and level of evidence, and classified as “identical”, “overlapping”, or “different”. Out of 32 recommendations compared, 26 recommendations (81%) were classified as identical or overlapping, and six recommendations (19%) were classified as different. Most diverging recommendations were related to minor differences in class of recommendation between the two documents. This applies to recommendations for reperfusion therapy >12 hours after symptom onset, immediate transfer of all patients after fibrinolytic therapy, rescue PCI for patients with failed fibrinolysis, and intra-aortic balloon pump use in patients with cardiogenic shock. More substantial differences were observed with respect to the type of P2Y12 inhibitor and duration of dual antiplatelet therapy.

Conclusions: The majority of recommendations for the management of STEMI according to ESC and ACCF/AHA guidelines were identical or overlapping. Differences were explained by gaps in available evidence, in which case expert consensus differed between European and American guidelines due to divergence in interpretation, perception, and culture of medical practice. Systematic comparisons of European and American guidelines are valuable and indicate that interpretation of available evidence leads to agreement in the vast majority of topics. The latter is indirect support for the process of review and guideline preparation on both sides of the Atlantic.

Introduction

The management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) has evolved during the last decades, resulting in an impressive decline in short- and long-term mortality1. Numerous clinical trials continue to investigate novel strategies, drugs, and interventions to improve outcomes further2-8. Guideline documents of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) summarise the available evidence and provide evidence-based recommendations to the medical community.

In 1990, the first ACC/AHA guideline on early management of patients with STEMI was released. Since then, several new/update documents have been published regularly every four years by both scientific societies as new diagnostic, pharmacologic and interventional strategies gained scientific evidence. In the 1990 guidelines, reperfusion with fibrinolysis (if not contraindicated) was the only type I indication. In both European and American 1998 guidelines, fibrinolysis and primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) when performed timely by an experienced team were type I indications. In 2004, primary PCI emerged as the preferred therapy but limitations in its applicability to most patients were recognised. The need for regional STEMI networks to increase timely PCI availability was highlighted. In 2008, European and American guidelines established that primary PCI was the preferred reperfusion strategy provided that is was available within 90 minutes in American and within 60 minutes in European guidelines. Specific recommendations concerning antithrombotic and antiplatelet therapies were also defined. Rescue PCI was still an option after failed thrombolysis or reocclusion. The ESC and ACCF/AHA have recently published updates of guidelines on the management of STEMI incorporating the most recent evidence9,10. We systematically compared the recommendations of these two documents in order to identify similarities and differences. It needs to be underscored that different settings and health systems are present on both sides of the Atlantic. This article does not aim to recommend new decision-making processes, but rather to highlight differences between the two documents and to stimulate discussion.

Methods

Guidelines of the ESC9 and ACCF/AHA10 on the management of STEMI were systematically reviewed for consistency on the following recommendations: reperfusion therapy, percutaneous coronary intervention techniques, fibrinolytic therapy, cardiac arrest, use of intra-aortic balloon pump, antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy. Individual recommendations of the ESC and the ACCF/AHA were matched, directly compared in terms of class of recommendation and level of evidence (LoE), and classified as “identical”, “overlapping”, or “different”. Recommendations were considered “identical” when content as well as class of recommendation and LoE between the two guideline documents were consistent. In cases where recommendations were phrased differently, the class of recommendation was consistent but the LoE differed, or the class of recommendation differed between the two documents but the overall content was comparable, recommendations were classified as “overlapping”. Conversely, recommendations were considered “different” when the class of recommendation did not match or the recommendation differed substantially. Classification was performed by consensus of two experienced cardiologists.

Results

The ESC and ACCF/AHA guidelines on the management of STEMI both update previous documents published four years earlier. The documents are similar in terms of length (ESC 40 pages, ACCF/AHA 41 pages) and structure. Both documents have the same number of authors (n=23). The ACCF/AHA document provides recommendations in writing in the body of the text, and summarises the most relevant recommendations in dedicated tables. Conversely, recommendations in the ESC document appear mainly in dedicated colour-coded tables. The ACCF/AHA guidelines provide an appendix with a description of authors’ and reviewers’ potential conflicts of interest. This section is available on the ESC website. In addition, the ACCF/AHA document includes a short introductory description of the reviewed evidence for the preparation of the document.

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN RECOMMENDATIONS

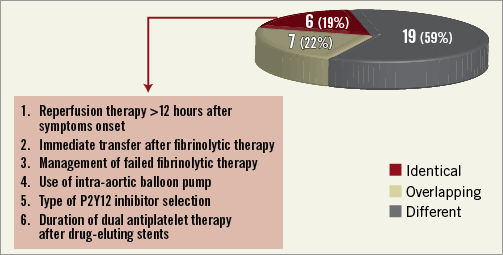

Reviewed recommendations and comparisons between guidelines are summarised in Table 1-Table 7. After exclusion of seven recommendations for which matching was not possible (i.e., recommendations listed in only one of the two documents), 32 recommendations were included in the present analysis. Out of these, 19 recommendations (59%) were classified as identical, seven recommendations (22%) were classified as overlapping, and six recommendations (19%) were classified as different.

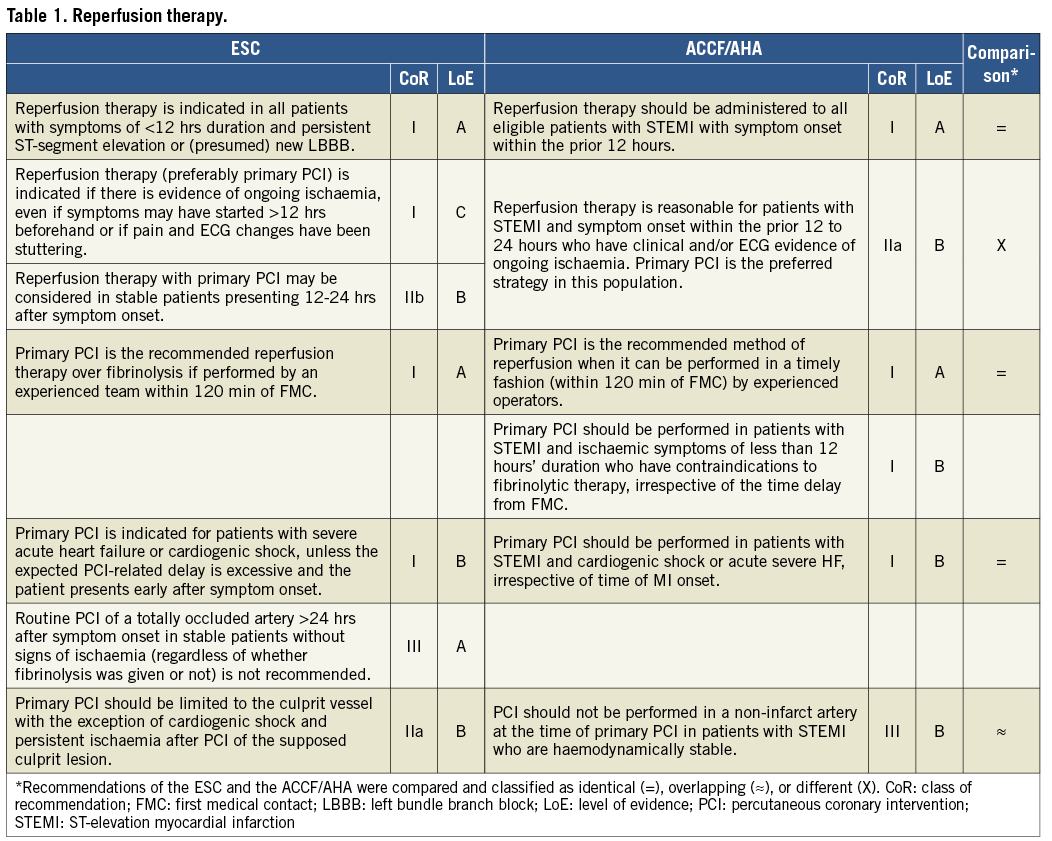

REPERFUSION THERAPY

ESC and ACCF/AHA recommendations on reperfusion therapy are summarised in Table 1. Reperfusion therapy assumes a consistent class I LoE A recommendation according to both guideline documents among STEMI patients with symptom duration <12 hours. Regarding patients with STEMI presenting more than 12 hours after symptom onset with evidence of ongoing ischaemia, the ESC guidelines recommend reperfusion therapy with class I LoE C whereas the ACCF/AHA guidelines provide a class IIa LoE B. In addition, the ESC guidelines –but not the ACCF/AHA guidelines– consider reperfusion therapy (class IIb, LoE B) for patients presenting 12-24 hours after symptoms onset irrespective of ongoing evidence of ischaemia.

Both ESC and ACCF/AHA documents recommend primary PCI for reperfusion (class I, LoE A) if performed by an experienced team within 120 minutes of first medical contact. The ACCF/AHA guidelines also recommend (class I, LoE B) primary PCI among STEMI patients and ischaemic symptoms of less than 12 hours duration who have contraindications for fibrinolytic therapy, irrespective of the time delay from first medical contact. Routine PCI in a totally occluded artery >24 hours after symptoms onset is not recommended (class III, LoE A) in stable patients without signs of ischaemia according to the ESC guidelines. Both documents agree on recommendation for primary PCI (class I, LoE B) among patients with cardiogenic shock or severe acute heart failure. According to the ESC guidelines, PCI should be limited to the culprit vessel (class IIa, LoE B) and, according to the ACCF/AHA guidelines, PCI of a non-infarct artery should not be performed (class III, LoE B) among haemodynamically stable patients.

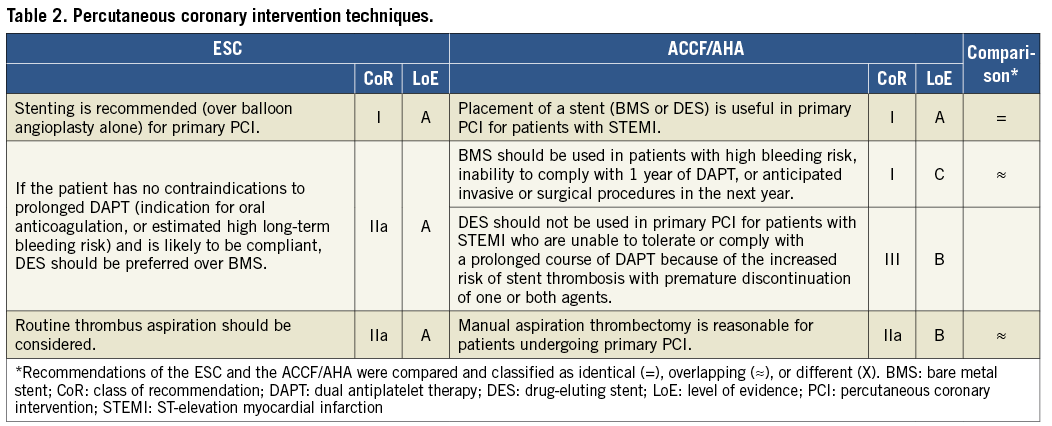

PERCUTANEOUS CORONARY INTERVENTION TECHNIQUES

Recommendations on primary PCI techniques according to ESC and ACCF/AHA are summarised in Table 2. Both documents recommend implantation of coronary artery stents during primary PCI with class I and LoE A. In relation to stent type, the ESC guidelines recommend the use of drug-eluting stents over bare metal stents in patients with no contraindications to prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy (class IIa, LoE A). The ACCF/AHA guidelines formulate these recommendations differently, by recommending the use of bare metal stents (class I, LoE C) in cases of patients at high bleeding risk, inability to comply with one-year dual antiplatelet therapy, or anticipated surgical procedures, and stating that drug-eluting stents should not be used for patients who are unable to tolerate or comply with a prolonged course of dual antiplatelet therapy (class III, LoE B). With respect to routine thrombus aspiration, the ESC and ACCF/AHA guidelines are consistent, with a class of recommendation IIa, but different LoE (A according to ESC and B according to ACCF/AHA).

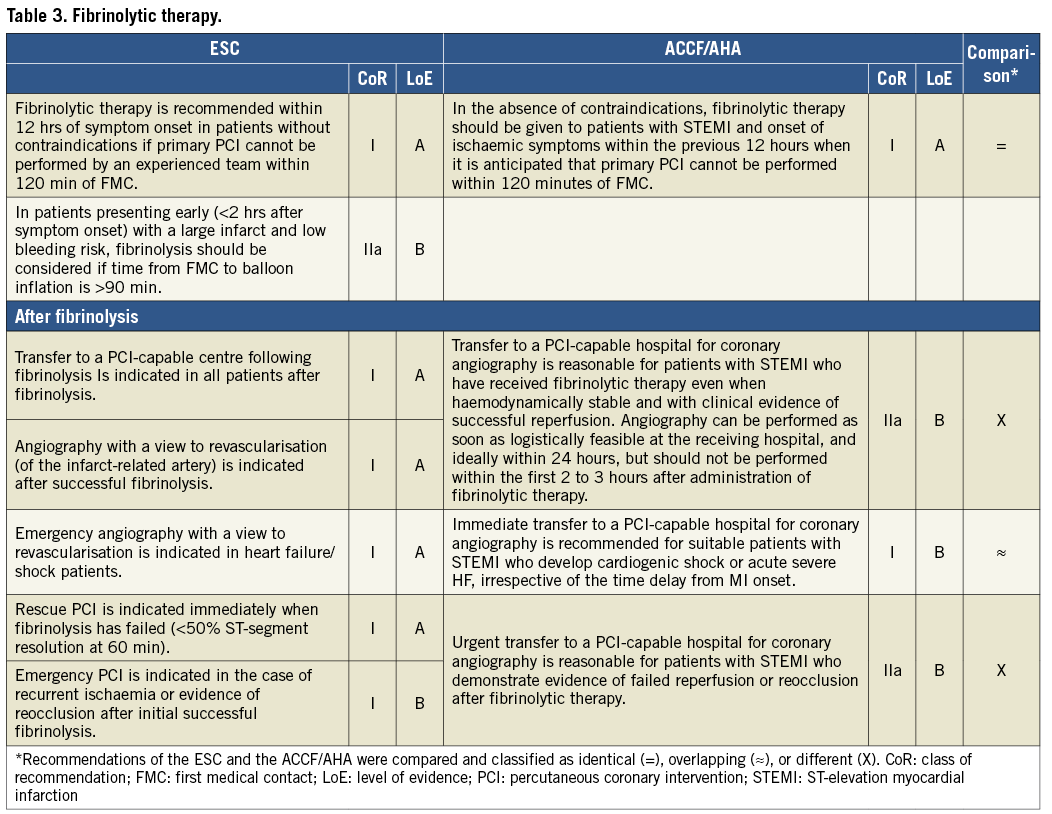

FIBRINOLYTIC THERAPY

Recommendations on fibrinolytic therapy are summarised in Table 3. The ESC and ACCF/AHA guidelines recommend (class I, LoE A) fibrinolysis in cases where primary PCI cannot be performed within 120 minutes of first medical contact among patients within 12 hours of symptoms onset in the absence of contraindications. The ESC guidelines also recommend fibrinolysis if the door-to-balloon time is >90 minutes among patients with large myocardial infarction and low bleeding risk presenting <2 hours after symptom onset (class IIa, LoE B).

After fibrinolysis, transfer of all patients to a PCI-capable centre assumes a class I LoE A recommendation in the ESC guidelines and a class IIa LoE B recommendation in the ACCF/AHA guidelines. In addition, ESC guidelines recommend (class I, LoE A) routine coronary angiography with a view to revascularisation of the infarct-related artery after successful fibrinolysis. Immediate transfer to a PCI-capable hospital is indicated (class I) for patients who develop cardiogenic shock or heart failure after fibrinolysis in both the ESC and ACCF/AHA guidelines, but with a different LoE (A according to ESC and B according to ACCF/AHA). The ESC guidelines recommend immediate rescue PCI in case of failed fibrinolysis (class I, LoE A), and emergency PCI in case of recurrent ischaemia after initial successful fibrinolysis (class I, LoE B). In contrast, transfer to PCI-capable hospitals for angiography is reasonable (class IIa, LoE B) after failed reperfusion or after reocclusion according to the ACCF/AHA guidelines.

CARDIAC ARREST

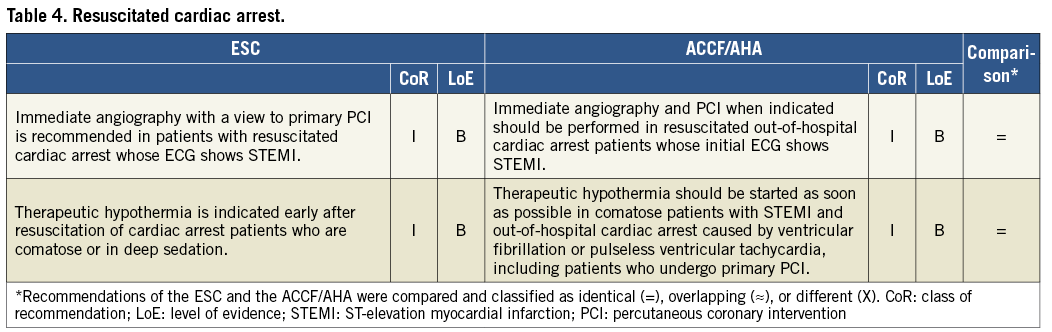

As summarised in Table 4, the ESC and ACCF/AHA guidelines recommend (class I, LoE B) immediate angiography among patients with resuscitated cardiac arrest whose ECG shows evidence of STEMI. Therapeutic hypothermia is consistently recommended (class I, LoE B) in these patients when comatose or in deep sedation.

USE OF THE INTRA-AORTIC BALLOON PUMP

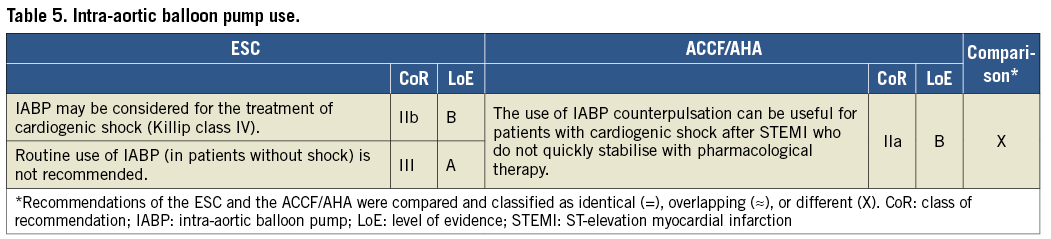

In patients with cardiogenic shock, use of the intra-aortic balloon pump may be considered (class IIb, LoE B) according to the ESC guidelines and should be considered (class IIa, LoE B) according to the ACCF/AHA guidelines (Table 5). Routine use of intra-aortic balloon pump is not recommended (class III, LoE A) according to the ESC guidelines, whereas this is not mentioned in the ACCF/AHA guidelines.

ANTIPLATELET THERAPY

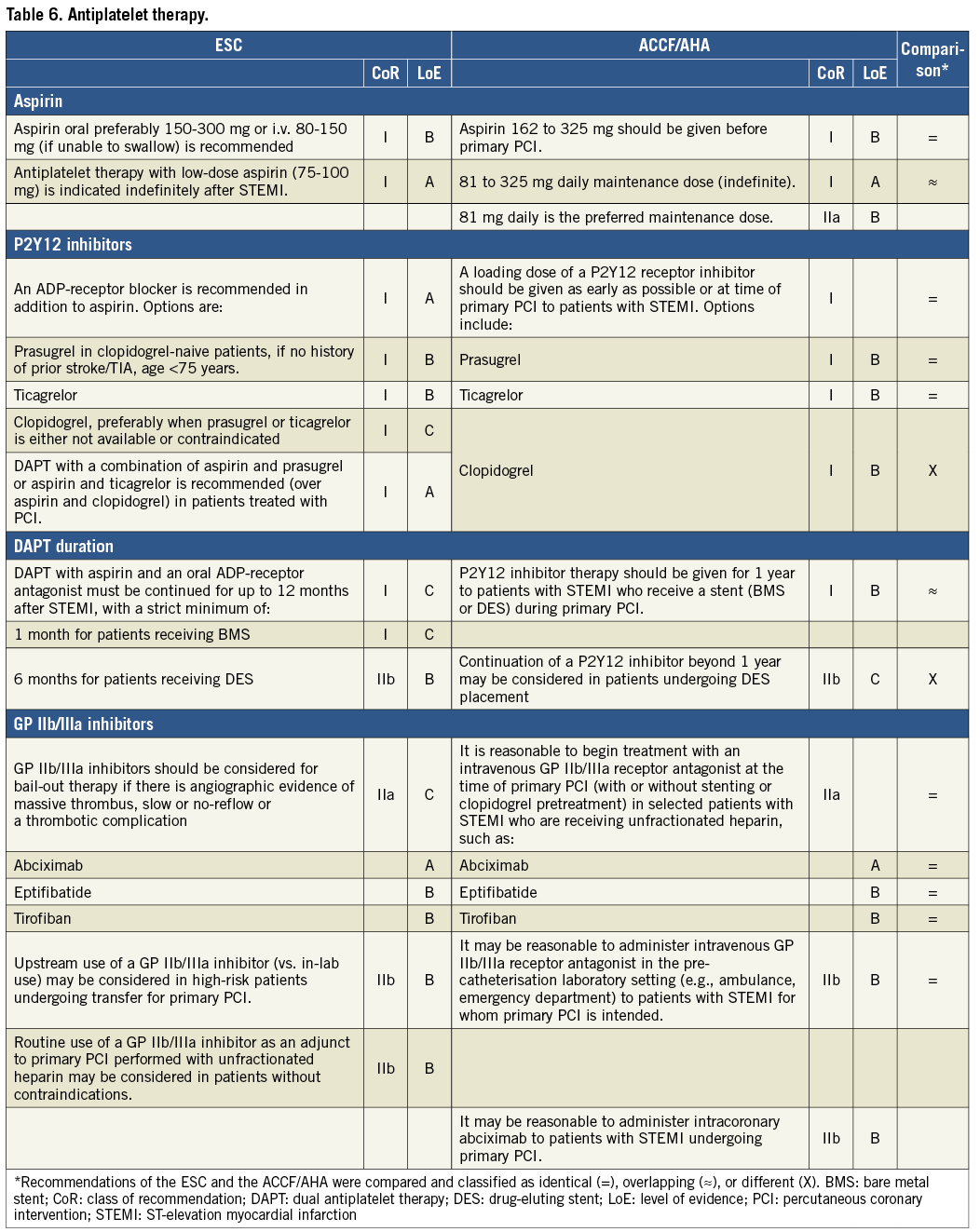

Recommendations on antiplatelet therapy are summarised in Table 6. Both documents recommend the use of aspirin (class I, LoE B). However, the ESC guidelines recommend low-dose aspirin for secondary prevention with class I and LoE A, whereas the ACCF/AHA guidelines provide a class IIa and LoE B recommendation.

Use of oral P2Y12 inhibitors assumes a class I recommendation in both the ESC and AHA guidelines. Regarding the selection of a specific P2Y12 inhibitor, the ESC guidelines restrict the use of clopidogrel to situations where prasugrel or ticagrelor is not available or contraindicated. Specifically, the ESC guidelines recommend dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and prasugrel or ticagrelor (over aspirin and clopidogrel) in patients treated with PCI (class I, LoE A). Conversely, the ACCF/AHA document does not reveal any preferential use of one over the other P2Y12 inhibitor. In relation to the duration of dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor, the ESC guidelines recommend up to 12 months duration (class I, LoE C), with a strict minimum of one month after bare metal stent implantation (class I, LoE C) and six months after drug-eluting stent implantation (class IIb, LoE B). According to the ACCF/AHA guidelines, dual antiplatelet therapy should be given for 12 months to patients receiving a stent (class I, LoE B), and continuation of a P2Y12 inhibitor beyond 12 months may be considered (class IIb, LoE C) after drug-eluting stent implantation.

The use of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors assumes a class IIa LoE C for bail-out therapy among patients with massive thrombus burden, slow or no-reflow phenomenon, or thrombotic complications in the ESC guidelines. Similarly, the use of intravenous GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors is reasonable (class IIa) at the time of primary PCI in selected patients – such as patients with large thrombus burden – who are receiving unfractionated heparin according to the ACCF/AHA guidelines. Upstream use of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors in the pre-hospital setting may be considered (class IIb, LoE B) among patients undergoing primary PCI according to both guideline documents.

ANTICOAGULANT THERAPY

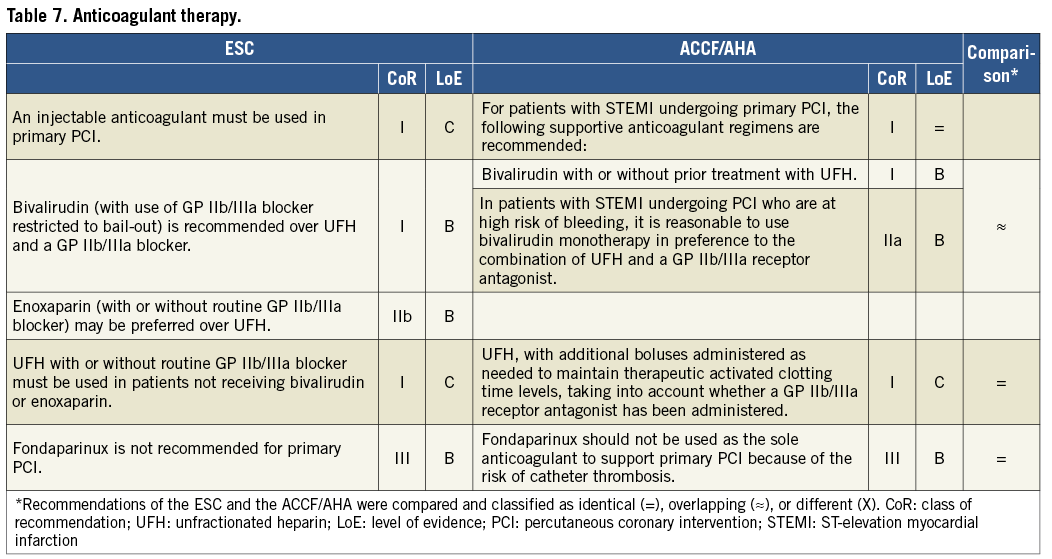

Recommendations on the use of anticoagulants are summarised in Table 7. Use of anticoagulant therapy has a class I indication according to both the ESC and the ACCF/AHA guidelines. The latter recommend preferentially bivalirudin with or without prior treatment with unfractionated heparin (class I, LoE B). Moreover, bivalirudin is recommended over unfractionated heparin with a GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor according to the ESC guidelines (class I, LoE B) and according to the ACCF/AHA guidelines (class IIa, LoE B). The use of unfractionated heparin in case bivalirudin is not used assumes a class I LoE C recommendation in both guidelines. The ESC but not the ACCF/AHA guidelines consider the use of enoxaparin (class IIb, LoE B) as preferable over unfractionated heparin. Finally, fondaparinux is not recommended (class III, LoE B) as an anticoagulant during primary PCI according to both the ESC and the ACCF/AHA guidelines.

Discussion

According to this systematic comparison of recommendations of ESC and ACCF/AHA guidelines on the management of STEMI, the majority of recommendations (81%) were identical or overlapping between the two guideline documents.

The main recommendations include early (<10 min) ECG at presentation, transfer to hospital by emergency services and STEMI networking organisation. PCI is the preferred method of reperfusion in patients presenting within 12 hours when performed in <90 min (preferably 60 min) if presentation is in a PCI-capable centre and <120 min (preferably 90 min) if initial presentation is in a non-PCI centre. Except for patients in cardiogenic shock, PCI should be limited to the culprit lesion. Radial approach, thrombus aspiration and DES implantation if appropriate are recommended in most cases. Prasugrel (if <75 years and no previous stroke/TIA) or ticagrelor is preferred over clopidogrel. Upstream use of IIb/IIIa inhibitors is not recommended. During PCI, bivalirudin or unfractionated heparin is recommended while fondaparinux is contraindicated. Dual antiplatelet therapy is recommended for one year, although in patients with high bleeding risk it may be limited to one month in the case of bare metal and to six months in the case of drug-eluting stents.

If timely PCI is not possible, fibrinolysis with a fibrin-specific agent is the best approach, particularly in patients with very early presentation (<2 hours since onset of symptoms). In patients with large infarcts and anticipated time to primary PCI >90 min, facilitated PCI with a fibrinolytic agent may be an option. Transfer to a PCI centre is recommended in all patients after fibrinolysis, even if fibrinolysis is initially successful. A coronary angiography in the interval three to 24 hours is appropriate in all patients.

In uncomplicated STEMI patients, early (72 hours) discharge is safe. Post-discharge recommendations include optimising coronary risk factor control, smoking cessation and participation in rehabilitation programmes. Medications include DAPT for one year, beta-blockers, ACE or ARB inhibitors, statins to achieve an LDL-cholesterol <70 mg/dl, aldosterone inhibitors in patients with left ventricular dysfunction and anticoagulation if indicated for left ventricular dysfunction or atrial fibrillation.

Differences between guidelines are summarised in Figure 1. The majority of diverging recommendations were related to differences in the class of recommendation between the two documents, although differences were usually minor. This applies to the indication to reperfusion therapy >12 hours after symptom onset in patients with ongoing ischaemia (class I LoE C according to ESC and class IIa LoE B according to ACCF/AHA), as well as to the indication to immediate transfer of all patients after fibrinolytic therapy irrespective of evidence of reperfusion (class I LoE A according to ESC and class IIa LoE B according to ACCF/AHA). Similarly, rescue PCI is recommended for patients with failed fibrinolysis (class I, LoE A) and for patients with reocclusion after initial successful fibrinolysis (class I, LoE A) according to the ESC guidelines as compared with a class IIa LoE B for both scenarios in the ACCF/AHA guidelines. Finally, regarding intra-aortic balloon pump use in patients with cardiogenic shock, the ESC guidelines provide a class IIb LoE B recommendation, whereas the ACCF/AHA guidelines maintain a class IIa LoE B recommendation.

Figure 1. Summary of differences between recommendations. Number (%) of recommendations classified as identical, overlapping, or different are shown in the pie chart (right). Recommendations resulting as different are summarised in the box (left).

More substantial differences were observed with respect to the type of P2Y12 inhibitor and duration of dual antiplatelet therapy. In contrast to the former, the ESC guidelines recommend preferring ticagrelor or prasugrel over clopidogrel (class I LoE A); conversely, the ACCF/AHA guidelines do not indicate a clear preference among available P2Y12 inhibitors. This may be related to different perceptions in Europe and the United States of the findings of the PLATO and TIMI-TRITON 38 trials, the two randomised studies investigating novel P2Y12 inhibitors in patients with acute coronary syndromes including STEMI2,3,11,12. In relation to duration of dual antiplatelet therapy, both guideline documents agree in recommending a duration of 12 months DAPT after STEMI. Nevertheless, the ESC guidelines are open to a shorter duration with a strict minimum of one month after bare metal stent implantation (class I, LoE C) and six months after drug-eluting stent implantation (class IIb, LoE B). Conversely, the ACCF/AHA guidelines are open to consider extended duration of DAPT beyond 12 months after drug-eluting stent implantation (class IIb, LoE C). This strategy is explained by the paucity of data on the topic of optimal DAPT duration after drug-eluting stent implantation13,14, which will hopefully be addressed by ongoing large-scale trials (NCT00977938, NCT00661206, NCT00822536). It is noteworthy that significant differences between the ESC and ACCF/AHA guidelines were mainly related to insufficient evidence at this point in time.

There are many other issues that have not been mentioned in this comparison of guidelines but which represent unresolved problems in the treatment of STEMI patients: improving appropriate and timely diagnosis of STEMI by medical and paramedical-run emergency units, the efficiency of network models in urban and non-urban areas, the best approach to late presenters, prevention and treatment of the no-reflow phenomenon and reperfusion injury, the potential benefit of bioabsorbable stent platforms in this setting, and prevention of left ventricular remodelling or the potential benefits of regenerative therapies. Research in these and other fields will lead to further improvement of short- and long-term outcome of STEMI patients.

Conclusions

The majority of recommendations for the management of STEMI according to ESC and ACCF/AHA guidelines were identical or overlapping. Differences were explained by gaps in available evidence, in which case expert consensus differed between European and American guidelines due to divergence in interpretation, perception, and culture of medical practice. Systematic comparisons of European and American guidelines are valuable and indicate that interpretation of available evidence leads to agreement in the vast majority of topics. The latter is indirect support of the process of review and guideline preparation on both sides of the Atlantic.

Conflict of interest statement

S. Windecker has received research contracts to the institution from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Biosensors, Cordis, and Medtronic. J.L. Zamorano has received research contracts to the institution from Abbott, MSD, and Philips. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.