Introduction

The prognostic benefits of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) arise primarily from the placement of a left internal mammary artery (LIMA) onto the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery. In contrast, the long-term patency rates of adjunctive conduits (including vein and radial grafts) placed onto the remaining vessels are less good, with approximately half becoming occluded within 10 years. Continuing improvements in stent technology have made it possible to treat increasingly complex disease with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and the long-term outcome rates with new-generation drug-eluting stents (DES) have improved significantly. Rather than considering each revascularisation technique in isolation, a hybrid approach utilises the potential benefits of both revascularisation techniques, and thus may improve long-term outcomes in selected patients. In this article, we will discuss the contemporary revascularisation strategies used in multivessel disease, review the available data for hybrid revascularisation and consider the need for a clinical trial that will provide the data most relevant to current practice.

Background

CABG is commonly reserved for patients with complex multivessel disease, especially involving the left main stem (LMS) or proximal LAD1. The excellent long-term patency rates for LIMA grafts to the LAD are undisputed (over 95% at 10 years) and thus make this conduit the gold standard as part of a surgical revascularisation strategy2,3. Unfortunately, the long-term patency of any necessary adjunctive saphenous vein grafts (SVG) placed on the remaining coronary arteries is not so good, with only 56% of SVGs to the right coronary artery (RCA) and 58% to the circumflex artery (Cx) remaining open at 10 years4. Total arterial grafting has been increasingly used, although only 12% of all CABG procedures in the run-in phase of the SYNTAX trial used total arterial grafting5. Furthermore, the choice of arterial conduit to the non-LAD vessel may be critical, with conflicting reports on the performance of radial artery grafts versus saphenous vein grafts. There are some data to suggest lower rates of graft occlusion with radial grafts6, although more recent randomised data have shown no differences in one-year patency between radial arterial conduits and SVGs (89% for both)7. The use of bilateral internal mammary arteries (BIMA) has also been investigated, with observational studies suggesting improved mortality of BIMA compared to single LIMA grafting8. However, the widespread use of BIMA grafting has been limited by a perceived increase in procedural complexity and early morbidity, in particular sternal dehiscence, most marked in diabetic patients9,10. Consequently, if undertaken, the commonest surgical procedure for multivessel disease involves the placement of a combination of venous and arterial grafts, with 81% of surgical patients in the run-in phase of the SYNTAX study treated by this approach5.

Didactically defined improvements in PCI have ensured that a less invasive approach may be appropriate in patients with multivessel disease, with the emergence of DES resulting in fewer restenoses and repeat revascularisation procedures compared to balloon angioplasty and bare metal stents (BMS)11. For straightforward lesions, the target lesion failure rate (mostly restenosis requiring a repeat PCI) at one year is as low as 4-5%12.

Recognising the relative advantages and drawbacks of both CABG and PCI has led to the concept of hybrid revascularisation, which could combine the advantages of LIMA grafting to the LAD with DES-PCI to any remaining coronary vessels.

Drug-eluting stents versus coronary artery bypass grafting

Several observational studies have compared CABG with DES placement in patients with multivessel disease. A recent pooled analysis of these studies included over 17,000 patients and showed that the risk of death with DES was similar to the risk with CABG (5.6% versus 5.9%, respectively; RR 1.18 [95% CI: 0.80-1.75]; p=0.39)13. Overall MACCE rates (defined as death, myocardial infarction [MI], stroke and repeat revascularisation) were higher in DES compared to CABG (7% versus 5%, respectively, p=0.002) being driven by higher rates of target vessel revascularisation (TVR) and higher rates of MI in PCI patients. Limitations of such observational studies, where patient characteristics often differed between the two treatment arms, suggest there is always selection bias.

The SYNTAX study was the largest prospective study with 1,800 patients with left main coronary disease and/or three-vessel disease randomised to either CABG or PCI using the TAXUS® paclitaxel-eluting stent (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA)14. At one year, PCI failed to meet the prespecified margin of non-inferiority compared to CABG. The increased primary endpoint of MACCE (combined death, MI, stroke and repeat revascularisation) was higher in patients treated with PCI (17.8% versus 12.4% for CABG; p=0.002), again driven by the need for repeat procedures in this group. Conversely, the stroke rate was significantly higher in the CABG-treated patients.

The three and five-year results of this landmark trial have recently been published and continue to demonstrate higher rates of MACCE in patients treated with PCI compared to CABG15,16. Again, one of the major driving factors was the increased need for repeat revascularisation in PCI patients compared to CABG, but there was also an increased risk of mortality and MI related to SYNTAX score, whilst stroke rates no longer differed between the two groups.

The SYNTAX score has been developed to risk stratify patients according to the severity of the coronary artery disease and this has given rise to three groups, the so-called “low-risk” patients (SYNTAX score 0-22), “intermediate-risk” patients (23-32) and “high-risk” patients (≥33)14. Three-year follow-up has shown no differences between CABG and PCI in patients with low SYNTAX scores but, in those with intermediate scores, MACCE is higher in PCI (27.4% versus 18.9%, p=0.02), driven by repeat revascularisation and increased MI. For the high-risk patients, except for stroke, the MACCE and all its components (including mortality) were significantly higher in PCI compared to CABG (34.1% versus 19.5%, p<0.001).

It would appear that CABG is the dominant revascularisation strategy for those with high (≥33) SYNTAX scores, whereas those with low scores are likely to undergo PCI due to comparable outcomes with surgery. For patients with intermediate SYNTAX scores, CABG may have an early advantage over PCI with lower rates of revascularisation at three-year follow-up. However, the majority (81% in the SYNTAX trial run-in phase5) of surgical patients receive a combination of arterial and venous grafts. Therefore, it is too soon to say whether long-term revascularisation outcomes (e.g., at 10 years) will indeed ultimately favour CABG. Further, the DES used was one that has repeatedly been shown to be inferior, especially in terms of the need for repeat revascularisation compared to the currently used new-generation DES12.

Drug-eluting stents compared with non-left internal mammary artery conduits

As previously discussed, a major weakness of CABG revascularisation is the attrition of SVGs17-19. In spite of only 10.7% of CABG patients requiring repeat revascularisation at three years in the SYNTAX study14, this figure is likely to increase over time as vein grafts deteriorate. At ten years, published data indicate that this figure could be as high as 50%4, although the contemporary use of aggressive statin therapy following CABG may improve long-term SVG patency20. DES have been in use for ten years, although there have been quantum changes in polymer bioneutrality, stent design and drug choice between old and new-generation stents which make long-term analysis of results less meaningful than the unchanged LIMA to LAD procedure. In the RAVEL study, the first-generation Cypher® sirolimus-eluting stent (Cordis, Johnson & Johnson, Warren, NJ, USA) was associated with 89.7% freedom from target lesion revascularisation (TLR) at five years21 and, in the j-Cypher registry of almost 20,000 lesions, TLR at five years was 15.9%22. The incidence within the first year was 7.3%, followed by an additional 2.2% per year for the remaining four years of follow-up. Ten-year outcome data from the DESIRE registry of 4,000 patients receiving DES since 2002 have shown target vessel revascularisation rates of only 5.3%23. While one might speculate that in the longer term contemporary DES may well be superior to the long-term results of SVGs, it must be emphasised that there have been no head-to-head randomised comparisons between DES and SVGs. With new-generation stents, the incidences of restenosis and stent thrombosis are further reduced, in part due to the cobalt-chromium platform enabling thinner stent struts. The rates of clinical restenosis at two years in the large observational Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Register (SCAAR) were 3.9% in new-generation DES compared to 5.8% in old-generation DES (and 7.4% in bare metal stents)24. Four-year data for the XIENCE everolimus-eluting stent (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) are available from the SPIRIT II trial, which randomised patients to XIENCE or TAXUS stents25. There was a trend towards lower rates of TLR with XIENCE (5.9% versus 12.7%, p=0.07), with very low rates (0.9%) of definite or probable stent thrombosis.

Thus, it might be reasonably argued that, with the contemporary longevity of DES but with no advances in conduit use, PCI would be superior to SVGs over the longer term. Coupled with the excellent patency of LIMA-LAD grafts, this has led to the under-considered concept of a hybrid approach to revascularisation.

Hybrid revascularisation

To date, the surgical aspect of the hybrid approach has typically used an “off-pump” strategy, which in some studies has been shown to reduce the risk of complications, including stroke and neurocognitive impairment26,27. Moreover, due to its anatomical course, the LIMA can be mobilised using minimally invasive direct (MID) techniques which appear under a number of guises, including MIDCAB, thoracoscopic MIDCAB, robotic MIDCAB and totally endoscopic MIDCAB28. Experienced operators have been able to achieve equivalent long-term outcomes compared to conventional LIMA-LAD grafting29-31.

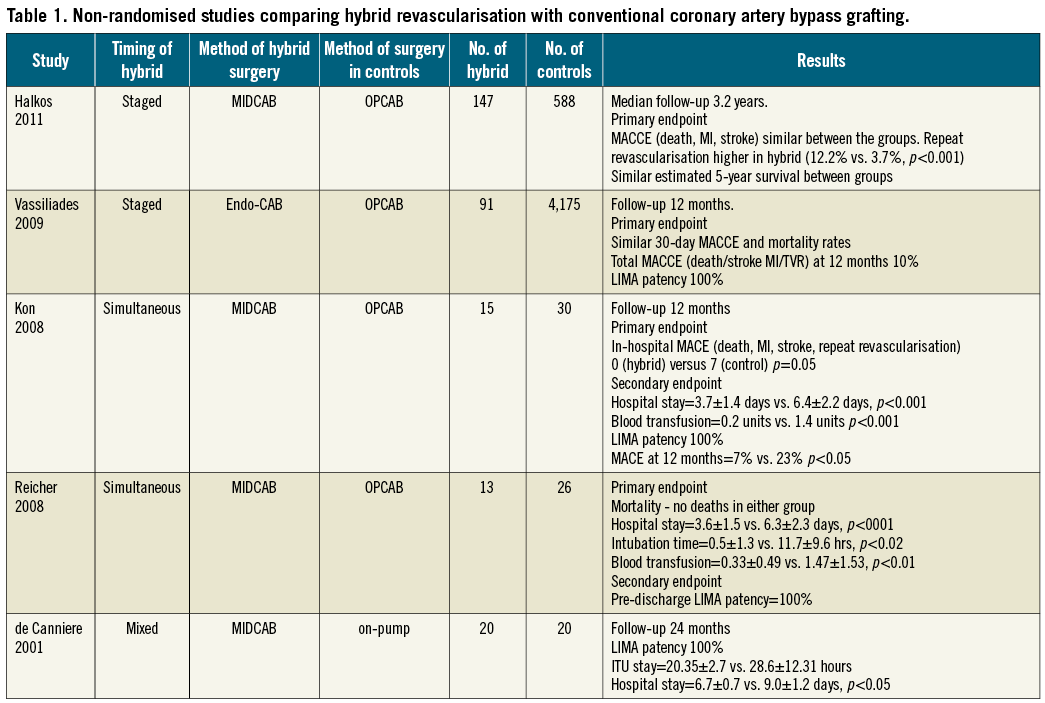

There have been numerous reports of successful hybrid revascularisation in patients with multivessel disease32-35, although only five small studies to date have compared the hybrid approach to traditional CABG and none of these was a randomised trial (Table 1). The first so-called “comparative” study was performed by de Canniere et al in 2001, where 20 patients with two-vessel coronary disease underwent hybrid revascularisation (CABG+PCI), with an interval between LIMA-LAD grafting and PCI of one to three days36. Comparisons were made with a group of 20 matched patients (according to age, sex, comorbidities, coronary anatomy and ejection fraction) undergoing conventional CABG. The hybrid procedure group had an event-free rate of 85%, compared to 35% in CABG arm (with defined events including episodes of atrial fibrillation, pericardial effusion, MI, blood transfusion requirement and leg wound dehiscence). Recovery was also more rapid in the hybrid group, with patients returning to work after 22±8 days compared to 89±22 days in conventional CABG patients (p<0.005). In 2008, Kon et al performed a study using a truly simultaneous approach, whereby MIDCAB LIMA-LAD grafting was immediately followed by PCI (with DES) to the remaining vessels35. All hybrid patients (n=15) received aspirin (325 mg) before the procedure, heparin during surgery (with no reversal on completion) and clopidogrel loading (300 mg) via a nasogastric tube on returning to the intensive care unit. They compared the hybrid procedures with 30 parallel matched controls and found that the hybrid approach resulted in no postoperative MACE (defined as MI, stroke, death or repeat intervention) compared to seven events in the OPCAB group (six MI, one stroke, p=0.05) Long-term graft patency was assessed using CT angiography and demonstrated one stent failure in the hybrid group compared to seven SVG failures in the OPCAB group (p=0.062). In a similar study in 2008, Reicher et al looked at 13 patients undergoing simultaneous hybrid revascularisation and compared them to 26 propensity score matched parallel controls undergoing off-pump CABG37. There were no deaths in either group, but hybrid patients had a shorter length of stay (3.6±1.5 versus 6.3±2.3 days, p=0.0001). Interestingly, hybrid patients required fewer blood transfusions than controls (21% versus 59%, p=0.05) despite the more aggressive antithrombotic regimen against a background of surgery in this group.

On a larger scale, Vassiliades et al compared 91 hybrid patients with a total 4,175 OPCAB procedures, making adjustments for selection bias using propensity scoring38. In contrast to the earlier studies, simultaneous revascularisation with surgery and PCI was not performed. Instead, 85 (93.4%) patients had LIMA to LAD grafting first, followed by PCI 2.2±1.2 days later. The remainder underwent PCI first, with surgery being performed 67.8±39.9 days later, and patients remained on clopidogrel throughout. Thirty-day MACCE (defined as death, MI, stroke and need for repeat intervention) rates were similar between the two study groups (1.1% in hybrid versus 3.0% in OPCAB, p=0.48). Kaplan-Meier survival estimates at three years did not differ significantly between groups (p=0.14).

The largest comparison of hybrid surgery with conventional OPCAB was conducted by Halkos and colleagues in 201139. A total of 147 patients underwent hybrid revascularisation (using endoscopic CAB ± robotic assistance + PCI) and were matched with 588 patients undergoing OPCAB (4:1 ratio) using an optimal matching algorithm. Patients were only included if the cardiologists felt that a “technically excellent” result from non-LAD stenting was possible, which generally excluded long lesions requiring multiple stents, small-calibre vessels, bifurcation lesions and chronic total occlusions (CTOs). In the Halkos study, fewer than 10 patients underwent simultaneous hybrid procedures, with the majority having surgery followed by PCI two to three days later, although some patients had PCI first if the non-LAD lesions were deemed “critical” (not clearly defined in the paper) in a joint decision between surgeon and interventional cardiologist. Patients undergoing surgery after PCI did so without interruption of clopidogrel. In-hospital outcomes were similar, with a 2% MACCE rate (composite death, stroke and MI) in each group. Repeat revascularisation was performed if clinically indicated and was higher in the hybrid group (12.2% versus 3.7%, p<0.001). This was driven by the need to treat LIMA-LAD lesions, progression of native disease and in-stent restenoses (3.4%). Only 2.4% of SVGs required intervention. Despite this, there were no differences in the estimated five-year survival (86.8% for the hybrid group and 84.3% for OPCAB group, p=0.61).

The results of the above trials demonstrate the feasibility of the hybrid technique, but many questions remain unanswered, including whether it is really worth considering as an approach, which patients may benefit most from this strategy, the logistics of performing two procedures instead of one, and the safety concerns regarding the choice of antiplatelet therapy.

Using hybrid revascularisation in clinical practice

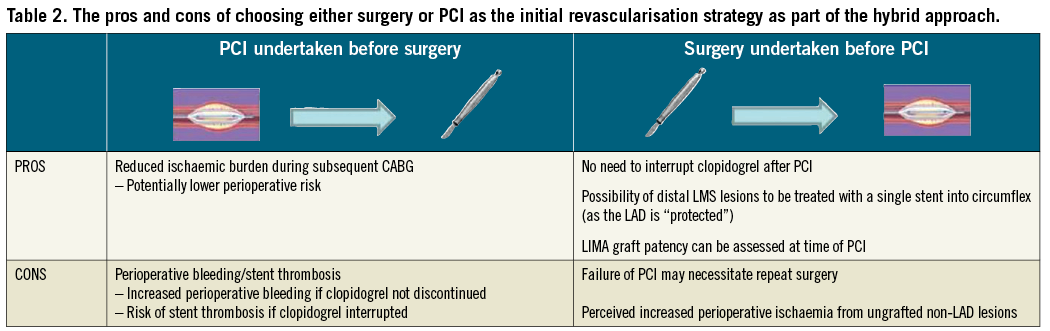

There are several patterns of disease that might be best treated with the hybrid approach but there are a number of issues which have yet to be addressed (Table 2), with the optimal order in which surgery and PCI should be performed being perhaps the most important consideration. In most studies to date the LAD has been LIMA-grafted first followed by PCI to the remaining vessels. This avoids performing surgery on patients who are taking clopidogrel, which is known to increase the risks of bleeding40. Of course there may be a perceived possibility of increased perioperative risk when performing incomplete surgical revascularisation in patients with critical RCA or Cx disease if surgery is to be performed before PCI or even failure of PCI to the non-LAD lesions. However, a recent large observational study suggested that the early and long-term survival was similar with incomplete compared to complete revascularisation, so long as a LIMA was placed onto the LAD41. If PCI was to be performed first, patients would either have to undergo surgery on clopidogrel, have it stopped for five to seven days or wait several months before it could be safely and permanently discontinued. A potential alternative might be to bridge with an intravenous P2Y12 receptor antagonist, such as cangrelor. This novel agent has been studied in patients who require interruption of a thienopyridine for CABG and may be a potential solution for those requiring surgery after PCI, although further data are required42. An oral version, ticagrelor, has been used in operative patients and is reversible and could be an alternative to clopidogrel in the hybrid patients. Finally, if surgery is performed first, one must be fairly confident that PCI is technically achievable, since subjecting a patient to repeat surgery for failed PCI would clearly increase the risk of morbidity and mortality.

Most of the hybrid data so far have been generated in centres with great expertise in performing minimally invasive LIMA grafting and even using hybrid operating rooms capable of facilitating combined surgery and PCI. This is clearly not consistent with global surgical and interventional practice. Furthermore, data from the most recent observational study suggest that the need for repeat revascularisation is higher when the LIMA-LAD graft is placed using a minimally invasive approach39. Consequently, there may be a reluctance among many cardiac surgeons to adopt a technique that appears to have a steep learning curve, involves longer operating times and may not achieve the same results as conventional surgery43.

There is therefore a need to develop a standard and universally accessible strategy to manage patients with RCA and Cx disease suitable for PCI and LAD disease suitable for LIMA.

Hybrid strategy: time for a trial?

Despite randomised studies comparing CABG and DES in multivessel disease, the optimal revascularisation strategy is far from clear and there are limitations with the SYNTAX trial that make it fall short of being the definitive study. Although the need for repeat revascularisation was higher with PCI than CABG at three years, long-term SVG patency data from other studies might indicate that revascularisation with CABG is likely to be higher over the longer-term follow-up. Furthermore, there was no mandate to use ischaemia testing to guide revascularisation, whereas the FAME trial (angiographic versus fractional flow reserve [FFR]-guided PCI) showed that FFR-guided PCI resulted in fewer stents being implanted, with a 30% reduction in the risk of death, MI or repeat revascularisation at one year44. Consequently, PCI may have been performed on non-flow-limiting lesions in the SYNTAX trial, perhaps reflected by one third of patients receiving more than 100 mm of stent. However, it should be acknowledged that FFR-guided CABG may also improve outcomes from surgery, perhaps by restricting the placement of grafts onto coronary vessels with functionally significant stenoses only.

Moving beyond the concept of hybrid revascularisation utilising a minimally invasive approach, perhaps a question more pertinent to real-world practice might be “could a hybrid strategy of conventional surgery to place LIMA-LAD (including full sternotomy/on-pump) plus DES-PCI to other vessels be a better way of managing multivessel disease than standard CABG?” One small non-randomised study has examined this strategy in 18 patients undergoing conventional CABG (majority on-pump) to place LIMA-LAD followed by DES-PCI to the remaining vessels 48 hours after surgery45. Comparisons were made with 18 matched controls (for baseline clinical characteristics and SYNTAX scores) undergoing conventional CABG with LIMA-LAD and at least one additional graft. The hybrid procedure was associated with shorter durations of cardiopulmonary bypass and there were no differences in bleeding or duration of hospital stay. One-year MACE rates (death, MI, target vessel revascularisation) were similar.

An appropriately sized randomised trial with relevance to the majority of patients requiring revascularisation for multivessel disease is probably needed, if only to put the question to bed. The “Could Hybrid In Multivessel disease bE the Rational Approach (CHIMERA)” study is being planned. Patients with multivessel disease amenable to both PCI and CABG would be randomised to either 1) conventional surgery (LIMA-LAD and either SVG/arterial conduits or RIMA to remaining vessels); 2) PCI to all vessels with contemporary DES (complemented by ischaemia testing); or 3) a hybrid approach using any strategy that places a LIMA graft onto the LAD (conventional sternotomy, on or off-pump technique or minimally invasive approach) and DES-PCI to the remaining vessels. Such a study may help patients to determine the best strategy to improve outcomes in the long term.

Conclusions

Whilst the long-term patency of LIMA to LAD grafts is excellent, SVGs placed on the remaining vessels are disappointing and the relatively short follow-up period for patients in randomised trials does not allow for the published attrition of SVGs. New-generation stents are associated with reduced rates of restenosis and thrombosis and, although there are no randomised trials comparing DES with SVGs, it is conceivable that stents may prove superior to vein grafts over a long follow-up period. The optimal revascularisation strategy in patients with multivessel disease is therefore still not fully resolved, not least because of the variation in disease patterns that make up “multivessel disease”. A hybrid approach combines the advantages of both CABG and PCI, although minimally invasive techniques used hitherto are not reflective of current surgical practice. Studies are badly needed to evaluate whether this approach can translate into better long-term outcomes for patients with multivessel disease.

Conflict of interest statement

A. Gershlick is on the advisory boards of, and on the lecture circuit for, Medtronic, Abbott, Boston Scientific and The Medicines Company. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.